Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4331

Peer-review started: May 29, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: August 8, 2020

Accepted: August 26, 2020

Article in press: August 26, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 121 Days and 7.5 Hours

Ovarian metastasis is a special type of distant metastasis unique to female patients with gastric cancer. The pathogenesis of ovarian metastasis is incompletely understood, and the treatment options are controversial. Few studies have predicted the risk of ovarian metastasis. It is not clear which type of gastric cancer is more likely to metastasize to the ovary. A prediction model based on risk factors is needed to improve the rate of detection and diagnosis.

To analyze risk factors of ovarian metastasis in female patients with gastric cancer and establish a nomogram to predict the probability of occurrence based on different clinicopathological features.

A retrospective cohort of 1696 female patients with gastric cancer between January 2006 and December 2017 were included in a single center, and patients with distant metastasis other than ovary and peritoneum metastasis were excluded. Potential risk factors for ovarian metastasis were analyzed using univariate and multivariable logistic regression. Independent risk factors were chosen to construct a nomogram which received internal validation.

Ovarian metastasis occurred in 83 of 1696 female patients. Univariate analysis showed that age, Lauren type, whether the primary lesion contained signet-ring cells, vascular tumor emboli, T stage, N stage, the expression of estrogen receptor, the expression of progesterone receptor, serum carbohydrate antigen 125 and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio were risk factors for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer (all P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed that age ≤ 50 years, Lauren typing of non-intestinal, gastric cancer lesions containing signet-ring cell components, N stage > N2, positive expression of estrogen receptor, serum carbohydrate antigen 125 > 35 U/mL, and a neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio > 2.16 were independent risk factors (all P < 0.05). The independent risk factors were constructed into a nomogram model using R language software. The consistency index after continuous correction was 0.840 [95% confidence interval: (0.774-0.906)]. After the internal self-sampling (Bootstrap) test, the calibration curve of the model was obtained with an average absolute error of 0.007. The receiver operating characteristic curve of the obtained model was drawn. The area under the curve was 0.867, the maximal Youden index was 0.613, the corresponding sensitivity was 0.794, and the specificity was 0.819.

The nomogram model performed well in the prediction of ovarian metastasis. Attention should be paid to the possibility of ovarian metastasis in high-risk populations during re-examination, to ensure early detection and treatment.

Core Tip: Which clinical characteristics in female patients with gastric cancer indicate a propensity for ovarian metastasis? Although some studies have analyzed the clinicopathologic features of this special metastatic gastric cancer, there is no good clinical risk factor model to predict the occurrence of ovarian metastasis. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical features of a large cohort, aiming to construct and validate a nomogram to predict ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer.

- Citation: Li SQ, Zhang KC, Li JY, Liang WQ, Gao YH, Qiao Z, Xi HQ, Chen L. Establishment and validation of a nomogram to predict the risk of ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer: Based on a large cohort. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4331-4341

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4331.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4331

According to the latest global epidemiological data (GLOBOCAN2018), gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignant tumor and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. The poor prognosis of gastric cancer is closely related to the occurrence of distant metastasis. Ovarian metastasis is a special type unique to female patients with gastric cancer. Ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer was first discovered in 1854. However, due to the limitations of clinicopathology at that time, Paget only described it as an ovarian tumor related to the dense fibrous components of gastric cancer[2]. In 1896, Friedrich Ernst Krukenberg first reported six cases of this mucous ovarian tumor with sarcoma-like properties[3], and Krukenberg tumor has gradually become a substitute name for ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer. In 1960, Woodruff and Novak defined this special ovarian metastatic tumor of gastric cancer as a secondary ovarian tumor with signet-ring cells filled with mucus and accompanied by sarcoma-like matrix proliferation after analyzing 48 cases of metastatic ovarian tumor[4], which was approved by the World Health Organization in 1973 and remains today[5].

The clinical diagnostic rate of ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer is low. A multicenter study over 22 years in Italy showed that only 63 of 2515 female patients with gastric cancer had ovarian metastasis[6]. Controversially, some researchers reported that the Krukenberg tumor detection rate at autopsy was as high as 33%-41%[7], which indicated that the actual situation might exceed the clinical diagnostic rate. The pathway of ovarian metastasis is still unclear, and traditional intraperitoneal seeding is being gradually abandoned[8], and lymphatic metastasis is currently a recognized pathway[9]. One study found that ovarian metastasis in early gastric cancer is mostly accompanied by vascular carcinoma thrombus or perigastric lymph node metastasis[10]. Ovarian metastasis occurs early and lacks specific clinical symptoms, resulting in a low diagnostic rate and insufficient interventions which leads to a poor prognosis[11].

Which type of gastric cancer is more likely to metastasize to the ovary? Although some studies having analyzed the risk factors, there is no reliable clinical risk factor model to predict the risk of ovarian metastasis. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical features of a large cohort of female patients with gastric cancer, aiming to construct and validate a nomogram to predict ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer.

We retrospectively collected a large cohort of female patients with gastric cancer who were hospitalized in the Chinese PLA General Hospital between January 2006 and December 2017. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Pathological diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma; (2) Ovarian metastasis confirmed as the source of gastric cancer by pathology; (3) Relatively complete clinical data; (4) Long-term follow-up status can be obtained; and (5) Informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Additional primary malignancies; (2) Previous ovarian surgery; and (3) Other metastatic sites except the ovary and peritoneum. The study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the ethical committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

Baseline data, primary tumor characteristics, and clinical factors related to ovarian metastasis, if present, were obtained. Data including age, electrocorticogram score, pregnancy history, gastric tumor location, Borrmann type, Lauren type, whether the primary lesion contained signet-ring cells, vascular tumor emboli, T stage, N stage, immunohistochemical expression of estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR)/human epidermal growth factor receptor-2, serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)/carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125)/CA19-9/CA72-4, and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR). Staging of gastric cancer was performed according to the Eighth Edition Staging Standard published by the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer in 2018.

Primary continuous variables were identified both as quantitative variables and categorical variables. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD, which were classified according to clinical cut-off values or statistical median. Categorical variables were presented in frequencies and proportions. Binomial and categorical data were evaluated using the Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. All the data were analyzed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) and R 3.6.3 (http://www.R-project.org; The R Foundation). The 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for intergroup differences, and P values less than 0.05 (two-sided) were considered statistically significant.

Logistic regression analysis was used in the primary dataset to identify the independent risk factors, based on which the nomogram was constructed by using R software. The nomogram validation was performed through repeated independent samplings (Bootstrap method). The calibration curve resulting from repeated samplings was used to compare the appearance and the bias-corrected models. The Harrell's consistency index (C-index) was used for discrimination analysis. The C-index provides the probability between the observed and predicted probability of gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis. Receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC curve) was operated by the nomogram model and independent risk factors. The Youden index was calculated by the ROC curve, when it was at its maximum, the model could take both sensitivity and specificity into account.

A total of 1696 female patients with gastric cancer were included in this study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis occurred in 83 of 1696 female patients, accounting for 4.9% of the total cases. The median diameter of primary gastric cancer was 5.0 (1.2-13.7) cm, and 12 cases (14.5%) were located in the upper area of the stomach, 34 (41.0%) in the middle, 29 (34.9%) in the lower, and 8 (9.6%) in two areas or the entire stomach. Thirty-five cases (42.2%) had signet-ring cell carcinoma, 27 (32.5%) with T stage < T4, 31 (37.3%) with N stage < N2, and 35 (42.2%) with peritoneal metastasis. Twenty-nine patients (34.9%) had increased serum CEA, 53 (63.8%) had increased CA125, 23 (27.7%) had increased serum CA19-9, and 36 (43.4%) had a NLR higher than 2.16. Other patient clinicopathological data are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Total cohort, n = 1696 | Ovarian metastasis, n = 83, (%) | Non-ovarian metastasis, n = 1613, (%) | P value |

| Age (yr) | < 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 50 | 544 | 55 (66.3) | 489 (30.3) | |

| > 50 | 1152 | 28 (33.7) | 1124 (69.7) | |

| ECOG score | 0.090 | |||

| 0-1 | 1490 | 68 (81.9) | 1422 (88.2) | |

| 2-5 | 206 | 15 (18.1) | 191 (11.8) | |

| Pregnancy history | 0.100 | |||

| ≤ 2 | 711 | 42 (50.6) | 669 (41.5) | |

| > 2 | 985 | 41 (49.4) | 944 (58.5) | |

| Gastric tumor location | 0.124 | |||

| Upper | 249 | 12 (14.5) | 237 (14.7) | |

| Middle | 821 | 34 (41.0) | 787 (48.8) | |

| Lower | 411 | 29 (34.9) | 382 (23.7) | |

| Two or more | 215 | 8 (9.6) | 207 (12.8) | |

| Borrmann type1 | 0.304 | |||

| Polypoid | 177 | 8 (9.6) | 169 (11.8) | |

| Ulcer localized | 538 | 24 (29.0) | 514 (35.9) | |

| Ulcer infiltrating | 591 | 35 (42.2) | 556 (38.9) | |

| Diffuse infiltration | 207 | 16 (19.3) | 191 (13.4) | |

| Lauren type12 | < T0.001 | |||

| Intestinal | 619 | 14 (21.2) | 605 (44.7) | |

| Diffuse | 599 | 34 (51.5) | 565 (41.7) | |

| Mixed | 202 | 18 (27.3) | 184 (13.6) | |

| Primary lesion containing signet-ring cells1 | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 1449 | 48 (57.8) | 1401 (86.9) | |

| Yes | 247 | 35 (42.2) | 212 (13.1) | |

| Vascular tumor emboli1 | 0.035 | |||

| No | 1054 | 36 (57.1) | 1018 (69.7) | |

| Yes | 470 | 27 (42.9) | 443 (30.3) | |

| T stage13 | < 0.001 | |||

| T1a | 37 | 1 (1.3) | 36 (2.4) | |

| T1b | 137 | 3 (3.8) | 134 (8.8) | |

| T2 | 389 | 10 (12.7) | 379 (25.0) | |

| T3 | 416 | 13 (16.4) | 403 (26.5) | |

| T4a | 452 | 37 (46.8) | 415 (27.2) | |

| T4b | 168 | 15 (19.0) | 153 (10.1) | |

| N stage14 | < 0.001 | |||

| N0 | 249 | 1 (1.3) | 248 (16.3) | |

| N1 | 432 | 12 (15.2) | 420 (27.6) | |

| N2 | 534 | 18 (22.8) | 516 (34.0) | |

| N3a | 266 | 32 (40.5) | 234 (15.4) | |

| N3b | 118 | 16 (20.2) | 102 (6.7) | |

| ER expression1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Negative | 1233 | 46 (55.4) | 1187 (80.6) | |

| Positive | 323 | 37 (44.6) | 286 (19.4) | |

| PR expression1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Negative | 939 | 55 (66.3) | 884 (82.8) | |

| Positive | 211 | 28 (33.7) | 183 (17.2) | |

| HER-2 expression1 | 0.463 | |||

| Negative | 1406 | 74 (89.2) | 1332 (91.5) | |

| Positive | 133 | 9 (10.8) | 124 (8.5) | |

| Serum CEA1 | 0.120 | |||

| ≤ 5 ng/mL | 903 | 54 (65.1) | 849 (56.4) | |

| > 5 ng/mL | 686 | 29 (34.9) | 657 (43.6) | |

| Serum CA1251 | < 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 35 U/mL | 1090 | 30 (36.1) | 1060 (73.4) | |

| > 35 U/mL | 437 | 53 (63.9) | 384 (26.6) | |

| Serum CA19-91 | 0.321 | |||

| ≤ 37 U/mL | 1116 | 61 (73.5) | 1055 (78.1) | |

| > 37 U/mL | 317 | 22 (26.5) | 295 (21.9) | |

| Serum CA72-41 | 0.252 | |||

| ≤ 10 U/mL | 1179 | 69 (83.1) | 1110 (87.5) | |

| > 10 U/mL | 173 | 14 (16.9) | 159 (12.5) | |

| NLR | 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 2.16 | 1230 | 47 (56.6) | 1183 (73.3) | |

| > 2.16 | 466 | 36 (43.4) | 430 (26.7) |

Eighteen related clinical variables were collected and analyzed. The results of the univariate analysis showed that age, Lauren type, whether the primary lesion contained signet-ring cells, vascular tumor emboli, T stage, N stage, immunohistochemical ER expression, immunohistochemical PR expression, serum CA125 and NLR were the risk factors for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer (all P < 0.05; Table 1).

Multivariate analysis showed that age ≤ 50 years, Lauren typing of non-intestinal, gastric cancer lesions containing signet-ring cell components, N stage > N2, positive expression of immunohistochemical ER, serum CA125 > 35 U/mL, and NLR > 2.16 were independent risk factors (all P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Characteristics | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age (yr, > 50/≤ 50) | 0.207 | 0.107-0.398 | < 0.001 |

| T stage (> T3/≤ T3) | 1.333 | 0.668-2.659 | 0.415 |

| N stage (> N2/≤ N2) | 2.745 | 1.377-5.470 | 0.004 |

| Lauren type (non-intestinal/intestinal) | 3.449 | 1.654-7.191 | 0.001 |

| Primary lesion containing signet-ring cells (yes/no) | 3.334 | 1.653-6.727 | 0.001 |

| Vascular tumor emboli (yes/no) | 1.762 | 0.932-3.329 | 0.081 |

| ER expression (positive/negative) | 2.716 | 1.366-5.400 | 0.004 |

| PR expression (positive/negative) | 1.195 | 0.562-2.541 | 0.644 |

| Serum CA125 (U/mL, > 35/≤ 35) | 4.568 | 2.447-8.527 | < 0.001 |

| NLR (> 2.16/≤ 2.16) | 1.949 | 1.021-3.718 | 0.043 |

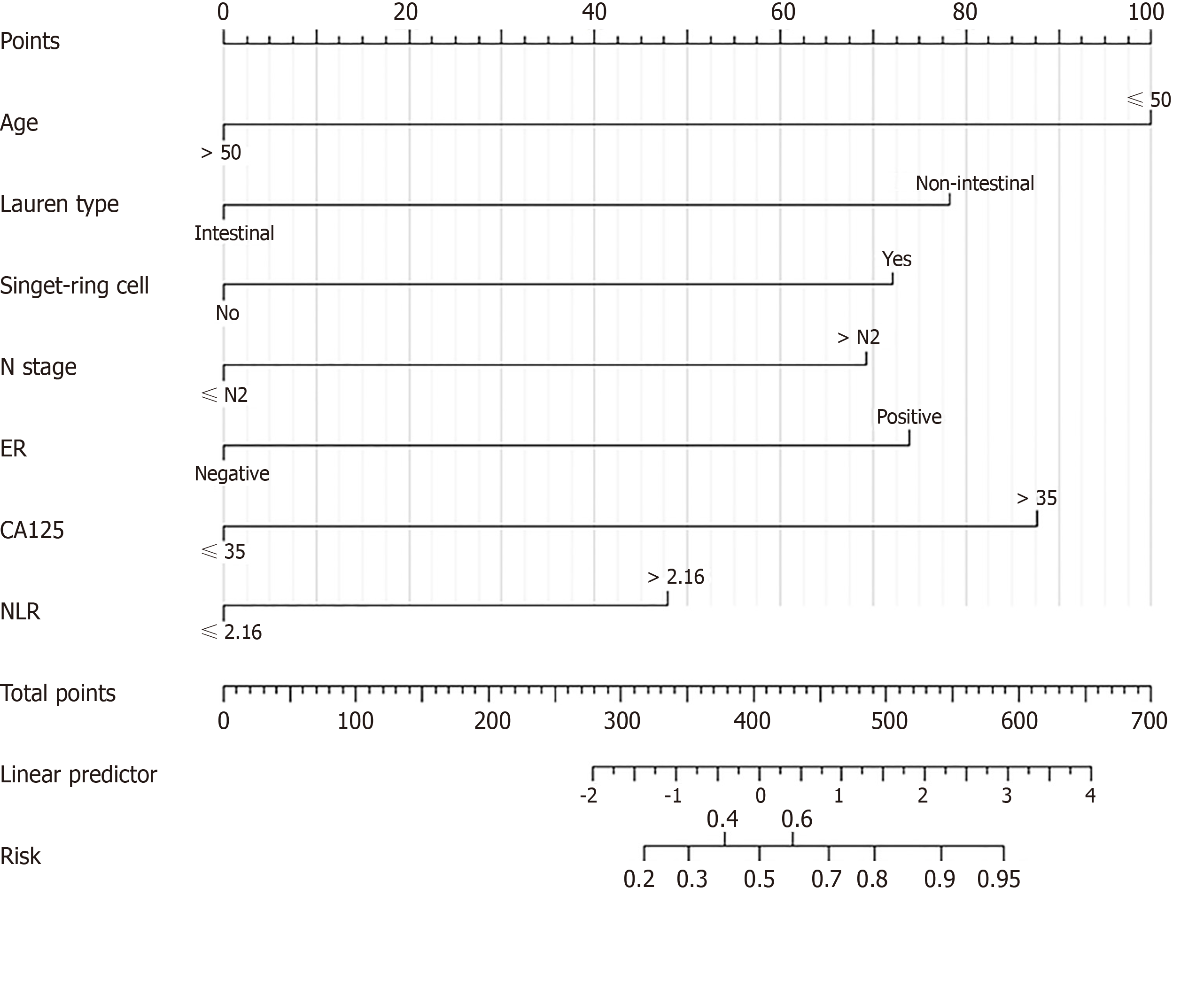

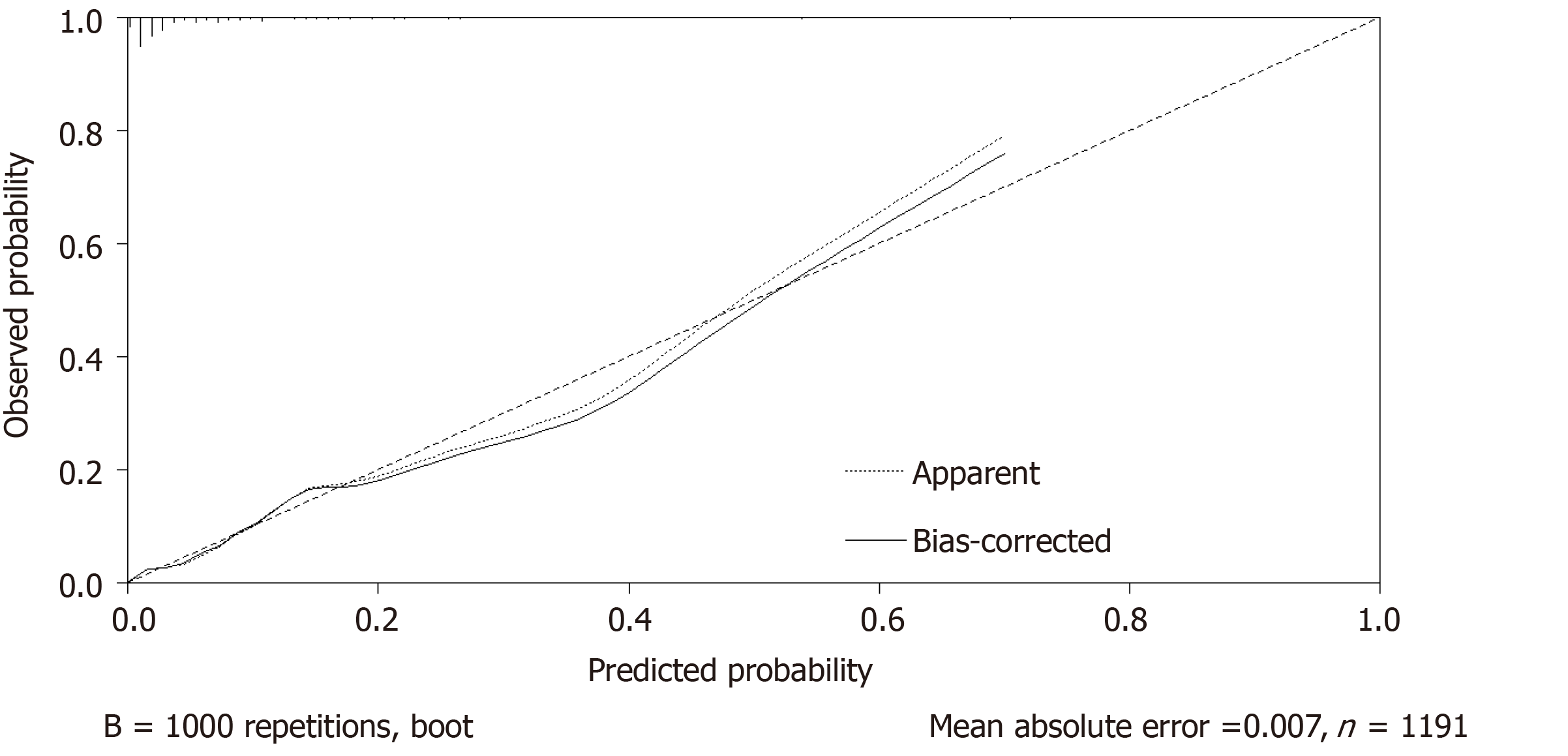

Independent risk factors were constructed into a nomogram model using R language software, in which different clinicopathological features were quantified into specific scores (Figure 1). The C-index after continuous correction was 0.840 [95%CI (0.774-0.906)]. After the internal self-sampling (Bootstrap) test, the calibration curve of the model was obtained with an average absolute error of 0.007, which suggested that the predicted probability was close to the real probability and that the model showed good consistency (Figure 2).

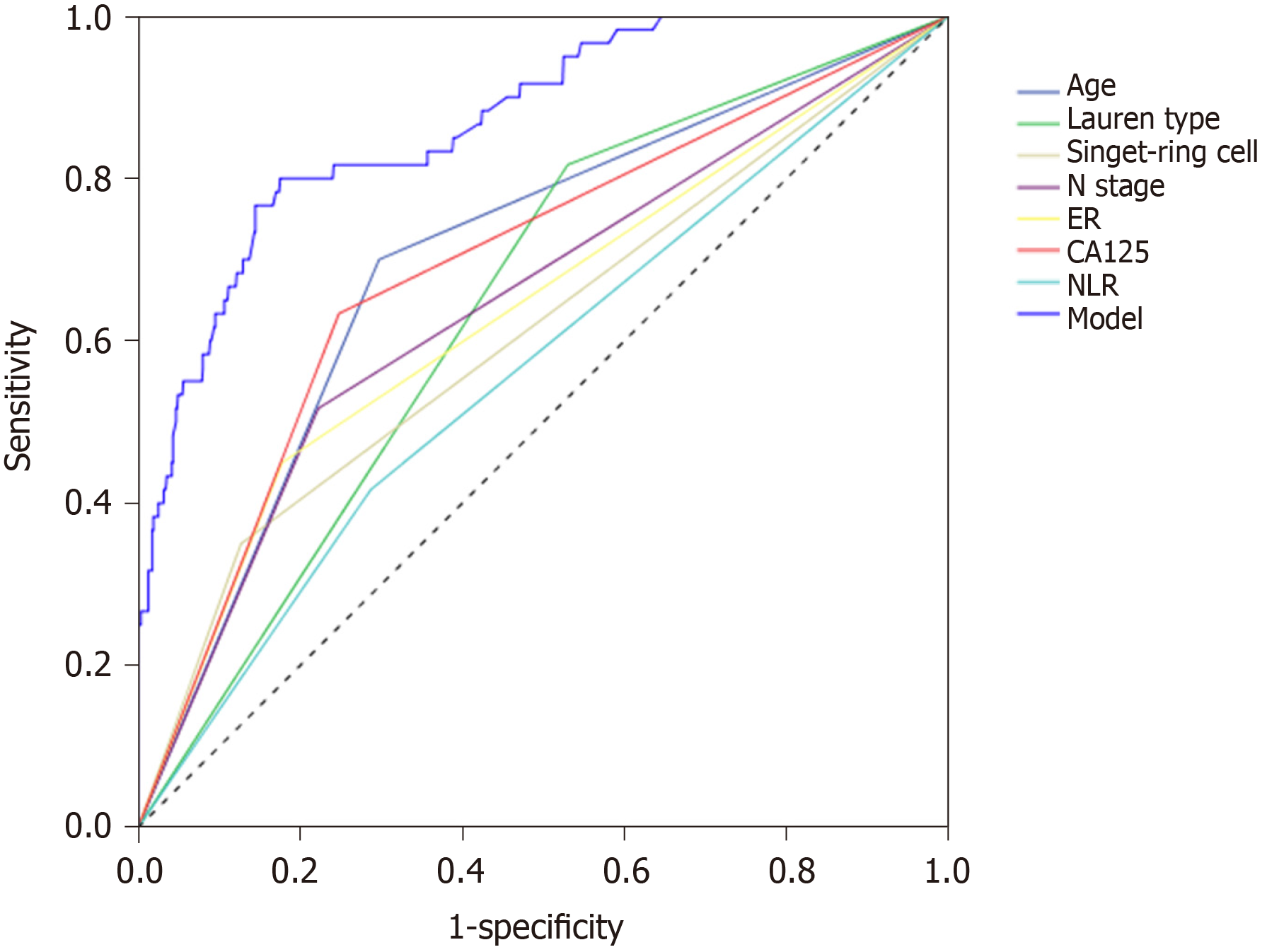

The ROC curve of the obtained model was calculated. The area under the curve of the model was 0.867, the Youden index was 0.613, the corresponding sensitivity was 0.794, and the specificity was 0.819 (Figure 3).

A total of 1696 female patients with gastric cancer were included in this study according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis occurred in 83 of 1696 female patients, accounting for 4.9% of the total cases. The median diameter of primary gastric cancer was 5.0 (1.2-13.7) cm, 12 cases (14.5%) were in the upper area of the stomach, 34 (41.0%) in the middle, 29 (34.9%) in the lower, and 8 (9.6%) in two areas or the whole stomach. Thirty-five cases (42.2%) were signet-ring cell carcinoma, 27 (32.5%) with T stage < T4, 31 (37.3%) with N stage < N2, and 35 (42.2%) with peritoneal metastasis. Twenty-nine patients (34.9%) had increased serum CEA, 53 (63.8%) had increased serum CA125, 23 (27.7%) had increased serum CA19-9, and 36 (43.4%) had NLR higher than 2.16. Other patient clinicopathological data are shown in Table 1.

Eighteen related clinical variables were collected and analyzed. The results of the univariate analysis showed that age, Lauren type, whether the primary lesion contained signet-ring cells, vascular tumor emboli, T stage, N stage, immuno-histochemical ER expression, immunohistochemical PR expression, serum CA125 and NLR were the risk factors for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer (all P < 0.05; Table 1).

Multivariate analysis showed that age ≤ 50 years, Lauren typing of non-intestinal, gastric cancer lesions containing signet-ring cell components, N stage > N2, positive expression of immunohistochemical ER, serum CA125 > 35 U/mL, and NLR > 2.16 were independent risk factors (all P < 0.05; Table 2).

Independent risk factors were constructed into a nomogram model using R language software, in which different clinicopathological features were quantified into specific scores (Figure 1). The C-index after continuous correction was 0.840 [95%CI (0.774-0.906)]. After the internal self-sampling (Bootstrap) test, the calibration curve of the model was obtained with an average absolute error of 0.007, which suggested that the predicted probability was close to the real probability and that the model showed good consistency (Figure 2).

The ROC curve of the obtained model was calculated. The area under the curve of the model was 0.867, the Youden index was 0.613, the corresponding sensitivity was 0.794, and the specificity was 0.819 (Figure 3).

Ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer is mostly occult growth without specific clinical manifestations in the early stage[12,13]. Few patients will have abdominal pain or distension, vaginal bleeding, menstrual disorders and other symptoms, which leads to a lack of timely detection and treatment. Some studies showed that patients with ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer were mainly premenopausal women, and the median age of ovarian metastasis was reported to be 42 years[14]. In our study, the median age of gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis was 44 (18-72) years, 53 (63.8%) cases were premenopausal, and 30 (36.2%) cases were postmenopausal. We performed univariate and multivariate analyses with age 50 as the dividing line, and the results showed that age < 50 years was a high-risk factor for ovarian metastasis (P < 0.001), which could be related to vigorous ovarian function caused by abundant blood flow and lymphatic reflux in premenopausal women.

The Lauren types of primary gastric cancer lesions can be divided into intestinal, diffuse and mixed type. Among them, the mixed type has the characteristics of both intestinal and diffuse type, but the main characteristics are similar to the diffuse type[15]. Generally, the diffuse type and the mixed type are collectively referred to as the non-intestinal type in the study. Lee et al[16] believed that Lauren typing was an important influencing factor related to the site and pattern of postoperative recurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma. Relevant studies have shown that non-intestinal gastric cancer is more common and prone to distant metastasis in young female patients with gastric cancer[17]. In this study, there were 34 cases of diffuse type and 18 cases of mixed type in patients with ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer, which accounted for 78.8% of the total number of cases, while this proportion was only 56.4% among all the patients enrolled. After further multi-factor regression analysis, it was found that the non-intestinal type was an independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis.

Traditionally, ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer was considered to be caused by the spreading and seeding of cancer cells. The necessary condition for the theory of implantation metastasis is the invasion of gastric cancer tumor cells into the serosa[2]. However, some studies have found that ovarian metastasis can also occur in patients with gastric cancer without tumor cells penetrating into the serosa[18]. In this study, there were 25 patients with T stage < T4, including 1 patient in T1a stage, 3 patients in T1b stage, and 28 and 13 patients in T4a and T4b stage, respectively. The results showed that whether the primary lesion broke through the serous layer was not an independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer.

Some studies have shown that ovarian metastasis can occur in early gastric cancer, which suggests that distant ovarian metastasis spreads via the rich structure of the lymphatic network in the mucosa and submucosa[19]. But why do tumor cells tend to migrate to the ovaries? Studies have shown that the expression of hormone-dependent ER may be closely related to the progression and deterioration of gastric cancer patients[20]; however, the specific mechanism remains unclear. In this study, we analyzed the expression of ER and PR in ovarian metastasis from gastric cancer. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that ER expression was an independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis (P < 0.05). However, whether hormone affinity characteristics bridge the migration of tumor cells still requires further validation.

CA125 is a tumor-associated glycoprotein antigen secreted by glandular epithelial cells, usually combining CEA, CA19-9 and CA72-4 as important serum tumor markers for early screening and postoperative review of gastric cancer, and some studies have shown that it is closely related to tumor progression and poor prognosis of gastric cancer[21,22]. A study by Huang et al[23] suggested that serum CA125 may be an important risk factor for peritoneal metastasis in gastric cancer. In this study, 53 of 83 patients with ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer had serum CA125 values higher than normal, accounting for 63.8% of cases, which was only 28.6% in the whole group of gastric cancer patients. Multivariate analysis showed that serum CA125 was an independent risk factor (P < 0.001). This reminded us of the possibility of ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer with elevated serum CA125, especially in women with gastric cancer whose elevated serum level was found during preoperative examination. If CA125 is found to be elevated in patients undergoing outpatient re-examination after gastric cancer surgery, the clinicopathological features of the patients should be re-evaluated and gynecological ultrasound or pelvic computed tomography should be added to further clarify the diagnosis.

Inflammatory factors affect the proliferation and migration of tumor cells through inflammatory mediators in the tumor microenvironment[24]. The mechanism is complex and has a significant research value. The NLR, an indicator of the specific variation in inflammatory factors related to the consistency of tumor progression, has received much attention in recent years. Choi et al[25] showed that the NLR can be used as an independent prognostic factor in patients with gastric cancer (especially those aged ≤ 50 years). An increase in the NLR may predict an increase in the positive rate of lymph node metastasis in patients with gastric cancer. The study by Kosuga et al[26] showed that the NLR can be used as an independent predictor of lymph node metastasis in advanced gastric cancer. In this study, the cut-off value of the NLR was used as the grouping standard, and the results showed that an NLR > 2.16 could be an independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer. Although it has low efficiency, it can be easily obtained as a supplement to the prediction of CA125 in the hematological examination.

Another highlight of our study is the construction and validation of the nomogram model. It has been reported that a nomogram model can be used to predict overall postoperative survival in gastric cancer patients[27,28]. However, no study has predicted the risk of ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer with a nomogram model. In this study, independent risk factors for ovarian metastasis of gastric cancer were included, and were quantified and scored according to different risk weights using regression analysis. A visual nomogram is constructed according to the proportion of risk coefficients. Due to the relatively small sample size, our study analyzed the data by binary variables. While the effectiveness of the test was not reduced, the predictive ability was successfully demonstrated by both internal re-sampling and ROC curves.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the risk factors associated with ovarian metastasis include age ≤ 50 years, more than six primary lymph node metastases, non-intestinal type (diffuse type or mixed type) in gastric cancer, signet-ring cell carcinoma, positive expression of ER, serum CA125 > 35 U/mL and a NLR > 2.16. The nomogram model of risk evaluation constructed by R language software can integrate all the risk factors and be simplified into an intuitive score. After validation, the risk of ovarian metastasis in female patients with gastric cancer can be more accurately assessed.

Ovarian metastasis is a special type of distant metastasis unique to female patients with gastric cancer. A prediction model based on risk factors is needed to improve the rate of detection and diagnosis.

Gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis is rarely reported and no study has shown the relationship between the clinicopathologic features and the occurrence of ovarian metastasis. We attempted to structure a visual model to help us predict the risk of ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer.

The present study aimed to analyze risk factors of ovarian metastasis in women with gastric cancer and establish a nomogram to predict the probability of occurrence based on different clinicopathological features.

A total of 1696 female patients diagnosed with gastric cancer were included. Potential risk factors for ovarian metastasis were analyzed using univariate and multivariable logistic regression. Independent risk factors were chosen to construct a nomogram which received internal validation.

Ovarian metastasis occurred in 83 of 1696 female patients. This study found that age ≤ 50 years, Lauren typing of non-intestinal, gastric cancer lesions containing signet-ring cell components, N stage > N2, positive expression of ER, serum CA125 > 35 U/mL, and a NLR > 2.16 were independent risk factors (all P < 0.05). A nomogram was constructed to quantitate the probability of the occurrence of ovarian metastasis which was internally validated.

The nomogram model performed well in the prediction of ovarian metastasis. Attention should be paid to the possibility of ovarian metastasis in high-risk populations during re-examination, to ensure early detection and treatment.

We will conduct a multi-center retrospective study and include more cases for analysis in the near future. External data from the SEER database will be used for further validation.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56679] [Article Influence: 7084.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 2. | Kiyokawa T, Young RH, Scully RE. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases with emphasis on their variable pathologic manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:277-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Krukenberg F. Ueber das Fibrosarcoma ovarii mucocellulare (carcinomatodes). Archiv fur Gynakologie. 1896;287-322. |

| 4. | Woodruff JD, Novak ER. The Krukenberg tumor: study of 48 cases from the ovarian tumor registry. Obstet Gynecol. 1960;15:351-360. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Scully RE, Sobin LH. Histologic typing of ovarian tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;111:794-795. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rosa F, Marrelli D, Morgagni P, Cipollari C, Vittimberga G, Framarini M, Cozzaglio L, Pedrazzani C, Berardi S, Baiocchi GL, Roviello F, Portolani N, de Manzoni G, Costamagna G, Doglietto GB, Pacelli F. Krukenberg Tumors of Gastric Origin: The Rationale of Surgical Resection and Perioperative Treatments in a Multicenter Western Experience. World J Surg. 2016;40:921-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Wang J, Shi YK, Wu LY, Wang JW, Yang S, Yang JL, Zhang HZ, Liu SM. Prognostic factors for ovarian metastases from primary gastric cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:825-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Agnes A, Biondi A, Ricci R, Gallotta V, D'Ugo D, Persiani R. Krukenberg tumors: Seed, route and soil. Surg Oncol. 2017;26:438-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamanishi Y, Koshiyama M, Ohnaka M, Ueda M, Ukita S, Hishikawa K, Nagura M, Kim T, Hirose M, Ozasa H, Shirase T. Pathways of metastases from primary organs to the ovaries. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011;2011:612817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kakushima N, Kamoshida T, Hirai S, Hotta S, Hirayama T, Yamada J, Ueda K, Sato M, Okumura M, Shimokama T, Oka Y. Early gastric cancer with Krukenberg tumor and review of cases of intramucosal gastric cancers with Krukenberg tumor. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1176-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Feng Q, Pei W, Zheng ZX, Bi JJ, Yuan XH. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors of 63 gastric cancer patients with metachronous ovarian metastasis. Cancer Biol Med. 2013;10:86-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SH, Lim KH, Song SY, Lee HY, Park SC, Kang CD, Lee SJ, Choi DW, Park SB, Ryu YJ. Occult gastric cancer with distant metastasis proven by random gastric biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4270-4274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Montacer KE, Haddad F, Kharbachi F, Tahiri M, Hliwa W, Bellabah A, Badre W. [Krukenberg tumour: about 5 cases]. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;34:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qiu L, Yang T, Shan XH, Hu MB, Li Y. Metastatic factors for Krukenberg tumor: a clinical study on 102 cases. Med Oncol. 2011;28:1514-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jiménez Fonseca P, Carmona-Bayonas A, Hernández R, Custodio A, Cano JM, Lacalle A, Echavarria I, Macias I, Mangas M, Visa L, Buxo E, Álvarez Manceñido F, Viudez A, Pericay C, Azkarate A, Ramchandani A, López C, Martinez de Castro E, Fernández Montes A, Longo F, Sánchez Bayona R, Limón ML, Diaz-Serrano A, Martin Carnicero A, Arias D, Cerdà P, Rivera F, Vieitez JM, Sánchez Cánovas M, Garrido M, Gallego J. Lauren subtypes of advanced gastric cancer influence survival and response to chemotherapy: real-world data from the AGAMENON National Cancer Registry. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:775-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee JH, Chang KK, Yoon C, Tang LH, Strong VE, Yoon SS. Lauren Histologic Type Is the Most Important Factor Associated With Pattern of Recurrence Following Resection of Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2018;267:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen YC, Fang WL, Wang RF, Liu CA, Yang MH, Lo SS, Wu CW, Li AF, Shyr YM, Huang KH. Clinicopathological Variation of Lauren Classification in Gastric Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2016;22:197-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schaefer IM, Sauer U, Liwocha M, Schorn H, Loertzer H, Füzesi L. Occult gastric signet ring cell carcinoma presenting as spermatic cord and testicular metastases: "Krukenberg tumor" in a male patient. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:519-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Al-Agha OM, Nicastri AD. An in-depth look at Krukenberg tumor: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1725-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ge H, Yan Y, Tian F, Wu D, Huang Y. Prognostic value of estrogen receptor α and estrogen receptor β in gastric cancer based on a meta-analysis and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) datasets. Int J Surg. 2018;53:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ghaderi B, Moghbel H, Daneshkhah N, Babahajian A, Sheikhesmaeili F. Clinical Evaluation of Serum Tumor Markers in the Diagnosis of Gastric Adenocarcinoma Staging and Grading. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2019;50:525-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhou H, Dong A, Xia H, He G, Cui J. Associations between CA19-9 and CA125 levels and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression in patients with gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:1079-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang C, Liu Z, Xiao L, Xia Y, Huang J, Luo H, Zong Z, Zhu Z. Clinical Significance of Serum CA125, CA19-9, CA72-4, and Fibrinogen-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Gastric Cancer With Peritoneal Dissemination. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8581] [Cited by in RCA: 8559] [Article Influence: 475.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choi JH, Suh YS, Choi Y, Han J, Kim TH, Park SH, Kong SH, Lee HJ, Yang HK. Comprehensive Analysis of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio for Preoperative Prognostic Prediction Nomogram in Gastric Cancer. World J Surg. 2018;42:2530-2541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kosuga T, Konishi T, Kubota T, Shoda K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Okamoto K, Fujiwara H, Kudou M, Arita T, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Otsuji E. Clinical significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Coimbra FJF, de Jesus VHF, Franco CP, Calsavara VF, Ribeiro HSC, Diniz AL, de Godoy AL, de Farias IC, Riechelmann RP, Begnami MDFS, da Costa WL. Predicting overall and major postoperative morbidity in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:1371-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen QY, Hong ZL, Zhong Q, Liu ZY, Huang XB, Que SJ, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Lu J, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Zheng CH, Huang CM. Nomograms for pre- and postoperative prediction of long-term survival among proximal gastric cancer patients: A large-scale, single-center retrospective study. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:3419-3435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hussein R, Tanabe H, Ueno M S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Xing YX