Published online Aug 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3591

Peer-review started: April 9, 2020

First decision: April 29, 2020

Revised: May 11, 2020

Accepted: July 16, 2020

Article in press: July 16, 2020

Published online: August 26, 2020

Processing time: 137 Days and 17.2 Hours

Phyllodes tumours (PTs) are fibroepithelial breast tumours, which can be classified as benign, borderline or malignant, according to their histological characteristics. While various huge borderline or malignant PTs have been previously described, a benign PT with a pulmonary nodule mimicking malignancy has not yet been reported. In order that doctors may have a comprehensive understanding of super-giant benign PTs (≥ 20 cm), we also performed a literature review to summarize the clinical features, differential diagnosis, and treatment of this disease.

A 42-year-old woman with severe anaemia presented with a rapidly enlarging right breast mass, measuring approximately 30 cm × 25 cm × 20 cm that was first noticed 1 year previously. A region of skin ulceration and necrosis (20 cm × 15 cm) was observed on the lateral side of the mass. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed a pulmonary nodule, which initially suggested a diagnosis of metastasis. CT showed that the boundaries between the pectoralis major and the mass were blurred, which was presumed to be due to tumour invasion. However, two core needle biopsies of the mass showed no evidence of malignancy. Following these results, the tumour was removed by mastectomy of the right breast. Interestingly, postoperative pathology finally proved the diagnosis of a benign PT. After 1 year of follow-up, wedge resection of the small pulmonary nodule was performed, and it was confirmed that the lung nodule was actually adenocarcinoma rather than metastatic breast cancer. The patient recovered very well without any postoperative treatment.

This case is unique in that the giant breast mass initially mimicking a malignant clinical presentation was eventually pathologically confirmed to be a benign PT, which misled the diagnosis and complemented the atypical features of benign PTs. The pathological and immunohistochemical results were important in the differential diagnosis. In addition, total mastectomy should be recommended due to difficulty in the precise diagnosis of PTs, especially in large breast masses. In the literature, almost one-half of super-giant benign cases were thought to be malignant tumours before surgery. This finding is a reminder to consider all conditions in order to make an accurate diagnosis and avoid excessive treatment.

Core tip: Phyllodes tumours (PTs) are fibroepithelial breast tumours. We report the unique case of a female patient who presented with a rapidly expanding breast PT. This case shows that a giant benign PT may reveal malignant features. The clinical manifestations and imaging examinations led us to misdiagnose this mass as a malignant tumour. However, pathological diagnosis of the tumour after complete excision confirmed the tumour to be a benign PT. The lung nodule was found to be adenocarcinoma rather than metastatic tumour. We also summarized and analyzed 12 cases and the results demonstrated that we should not to be fooled by appearances. All conditions should be considered to make an accurate diagnosis, in order that patients are given the appropriate treatment and avoid excessive treatment.

- Citation: Zhang T, Feng L, Lian J, Ren WL. Giant benign phyllodes breast tumour with pulmonary nodule mimicking malignancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(16): 3591-3600

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i16/3591.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3591

Phyllodes tumours (PTs) are rare fibroepithelial lesions with the proliferation of stromal and epithelial elements. The other two fibroepithelial lesions are fibroadenomas and hamartomas[1]. The World Health Organization formally referred to this disease using the term “phyllodes tumour” in 2003. Phyllodes tumours exhibit a growth pattern of excessive proliferation of leaf-like stroma into dilated clefts[2]. The incidence of PTs is low at only 2.5% of fibroepithelial lesions and 0.3%–1% of all primary breast tumours[3]. According to their histologic grade, PTs can be classified into benign (60%-75%), borderline (15%-20%) and malignant (10%-20%)[4-6]. Most cases occur in women aged 40-50 years, and cases in males have been reported occasionally[7,8]. The preferred treatment for PT is surgical removal, and as lymph node metastasis is rare, axillary lymph node dissection is not routine[2].

Many reports have described various large borderline or malignant PTs. However, a benign PT with lung nodule mimicking malignancy has not yet been reported. Here, we present the unique case of a female patient who developed a rapidly expanding PT mimicking malignancy, which misled the diagnosis. However, pathological diagnosis of the tumour after complete excision eventually confirmed a benign PT, and the accompanying lung nodule proved to be adenocarcinoma. The atypical clinical symptoms and confusing images of this benign PT make this case special. We searched PubMed from inception to September 2019 for “large OR huge OR massive OR giant OR big”, “phyllodes tumour” and “benign” as key words. We summarized and analyzed 12 cases of super-giant benign PTs (including our case) in order that doctors have a comprehensive understanding of this disease.

A 42-year-old Asian female presented with a rapidly enlarging right breast mass, which was originally noticed 1 year previously.

Over the past month, the breast mass had rapidly enlarged with symptoms of ulceration, bleeding and fever.

The patient had an unremarkable previous medical history.

On physical examination, the patient had a large right breast mass measuring 30 cm × 25 cm × 20 cm. It involved the whole right breast with a 20 cm × 15 cm area of ulceration complicated by necrosis located in the upper outer quadrant, which had a cauliflower-like neoplasm inside and was accompanied by an overpowering rotten stench. The skin of the right breast was stretched thin with superficial varicose veins, and the nipple was obviously enlarged (Figure 1A and B).

The basic condition of the patient was poor with severe anaemia and hypoalbuminaemia at the time of admission. Blood analysis revealed red blood cells of 2.2 × 1012/L, hemoglobin of 59 g/L, and albumin of 19.9 g/L, with a normal platelet count.

Due to ulceration and the sheer size of the breast mass, the patient was unable to undergo mammography or mammary magnetic resonance imaging. Breast ultrasound revealed an enormous mass with solid components occupying the entire breast. A contrast-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) scan displayed the giant breast mass (Figure 2A and B), and a pulmonary nodule of 8 mm × 6 mm in the left lung, which was initially considered metastatic (Figure 2C). The right pectoralis major was coarse locally, and the boundaries between the mass and the pectoralis major were unclear, which was thought to be due to tumour invasion (Figure 2D). There were no suspicious findings in the left breast or axillary nodes, and other examinations were normal.

The patient was further evaluated with a core needle biopsy. The first core needle biopsy of the massive tumour suggested mammary adenosis. However, this did not rule out the possibility of malignancy. Dillon et al[5] reported that approximately 39% of breast diseases may give false negative results. In addition, as the mass was large, the core needle biopsy was unable to cover the entire area. A second biopsy was then performed, which consequently revealed lymphadenitis with neoplastic cells. Both biopsies found no evidence of malignant tumour. Subsequently, a right mastectomy without resection of the axillary lymph nodes was recommended[3].

According to postoperative histological examination, the patient was diagnosed with benign PT.

The patient refused the suggested reconstructive breast surgery, due to its high cost. A right mastectomy without resection of the axillary lymph nodes was performed. The minimum surgical margin of the mass was 1 cm. Accordingly, making use of the superior and inferior skin flaps (even the skin directly overlying the mass which was normal) (Figure 3A and B), the skin closure was approximated after excision of the giant mass. Dissection revealed that the tumour was partly adhered to the pectoralis major muscle, rather than invading the muscle.

The excised breast mass was 25 cm × 20 cm × 16 cm in size, and weighed 3.5 kg. Due to severe ulceration of the tumour before surgery, the patient underwent debridement and dressing changes every day. The weight of the tumour was reduced compared with that on admission. Cystic and solid lobulated changes could be seen after incision of the tumour (Figure 4A). Postoperative histological examination was consistent with benign PT with negative margins (Figure 4B). Histologic sections revealed a circumscribed lesion with a variable leaf-like growth pattern (Figure 4C), low-to-moderate stromal cellularity, minimal stromal cell atypia, and absent stromal overgrowth and mitoses (Figure 4D). The Ki-67 proliferation index of the tumour was 1% for the stromal component (Figure 4E). The P53 index for the stromal component was focally positive and consistent with benign stromal proliferation (Figure 4F). All of these analyses showed no evidence of malignancy.

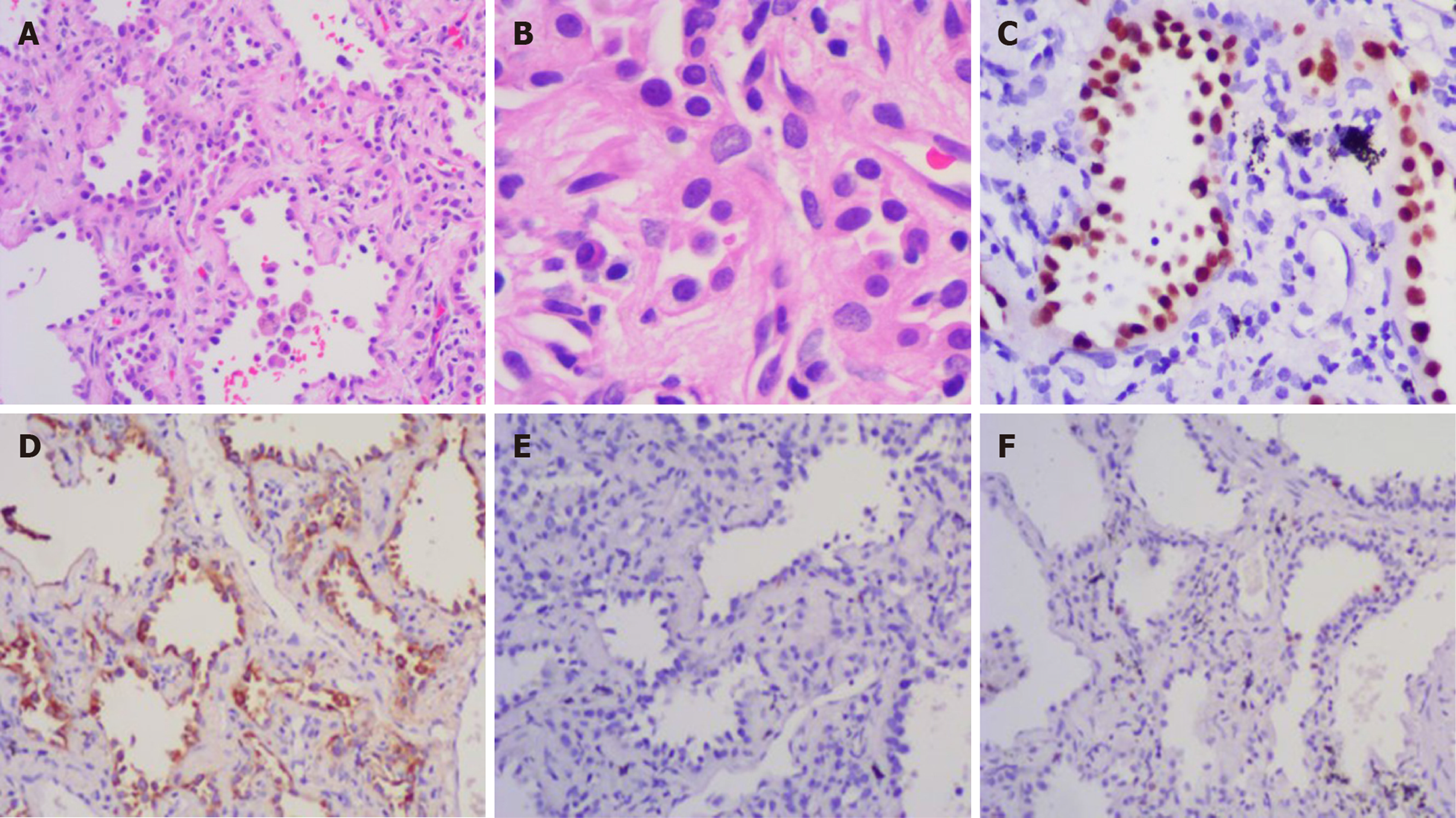

The patient has recovered very well without any postoperative treatment. No recurrence or metastasis was observed 12 mo after her breast operation, and wedge resection of the small lung nodule was performed after 1 year of follow-up, which confirmed the pulmonary nodule to be adenocarcinoma, rather than metastatic breast cancer (Figure 5A and B). Immunohistochemical results showed that thyroid transcription factor-1 and napsin-A were positive (Figure 5C and D) and GCDFP-15 was negative (Figure 5E). Ki-67 was focally positive (Figure 5F). The patient provided written informed consent for publication of the case details.

This case is interesting in that the patient had a giant benign PT with a pulmonary nodule mimicking malignancy, the patient also had severe anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia and infection. It was confusing and extremely difficult to diagnose whether the tumour was benign or malignant at first due to the following features: (1) The mass which was more than 30 cm with skin ulcers and necrosis increased rapidly in size in a short time. The patient had significant anaemia and malnutrition, which was more like cachexia. (2) CT showed there were no clear boundaries between the mass and pectoralis major, which was considered tumour invasion. (3) The pulmonary nodule was thought to be metastasis preoperatively, according to the chest CT and her breast disease. These findings suggested a diagnosis of malignant PT until postoperative pathology proved the breast mass was a benign PT. The reasons for this confusion were as follows: (1) Abundant vessels supported the tumour, resulting in the patient’s poor overall condition and cachexia. (2) Intraoperative findings revealed there was no infiltration between the mass and pectoralis major, only local adhesion. (3) The pulmonary nodule, which was resected by video-assisted thoracic surgery, was a primary lung adenocarcinoma, rather than breast metastasis.

The average size of PTs are usually 4-7 cm[9]. Giant PTs usually have a diameter of more than 10 cm[10]. It was reported that the largest benign PT even exceeded 50 cm[4]. We searched PubMed from inception to September 2019 for “large OR huge OR massive OR giant OR big”, “phyllodes tumour” and “benign” as key words. We summarized and analyzed 12 cases of super-giant benign PTs (including our case) that exceeded 20 cm. These cases as well as the one presented are shown in Table 1[4]. The majority of cases presented with rapid growth. The clinical characteristics of seven cases, including our case, were ulceration, bleeding or infection[1,2,6,7,10-12]. The huge masses in four cases were adherent to the pectoral muscle[3,10,11,12]. Our case is unique in that it is the first report of a patient with a super-giant PT presenting atypical clinical manifestations with a co-diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. In the literature, only one other patient presented atypical clinical manifestations[11], and in one other case the PT was combined with another malignant tumour[8].

| Ref. | Age | Disease duration | Size/weight | Clinical characteristics | Pectoral muscle adherence | Pre-op diagnosis/core biopsy | Surgery/margins | Recurrences |

| Miyaguni et al[20] | 43 | 5 mo | 20 cm/unknown | Ulceration, bleeding | No | Malignant/Unknown | Mastectomy/unknown | Unknown |

| Udapudi et al[21] | 21 | 3 mo | 45 cm/6.5 kg | Ulceration | No | Benign PT/Benign PT | Mastectomy/unknown | None for 2 yr |

| Liang et al[22] | 64 | 2 yr | 36 cm/unknown | No | Yes, suggested invasion | Malignancy not excluded/Highly atypical cells | Mastectomy, partial PME /< 1 cm | None for 7 yr |

| Zhao et al[23] | 63 | 2 yr | 45 cm/11 kg | No | No | Unknown/Unknown | Mastectomy, peripheral muscle excision /unknown | Unknown |

| Likhitmaskul et al[24] | 35 | 5 mo | 20 cm/unknown | Gestation | No | Benign PT/Benign PT | Mastectomy, LNs removed/unknown | Unknown |

| Sbeih et al[25] | 41 | 7 yr | 25 cm/unknown | Ulceration | No | Malignancy not excluded/Pseudoangiomatous or PT | Mastectomy, skin graft/negative margins | Unknown |

| Islam et al[4] | 44 | 1 yr | 50 cm/unknown | Ulceration, fungating, anaemia, malnourished | No | Benign PT/Benign PT | Mastectomy, partial PME, LN samples, LD flap closure/unknown | Died of MPE after 6 mo |

| Yan et al[26] | 54 | 6 mo | 20 cm/unknown | Non-myoepithelial tumour of the parotid | No | Malignancy not excluded/Fibroepithelial lesion | Mastectomy, PME, LN samples/adequate margins | None for 3 mo |

| Kallam et al[27] | 32 | 8 mo | 20 cm/unknown | Gestation | No | Benign PT/Benign PT | Mastectomy/unknown | None for 4 wk |

| Rathore et al[28] | 25 | 6 wk | 30 cm/5 kg | Fungating, anaemia | Yes | Benign PT/Benign PT | Mastectomy, PME/> 2 cm | None for 10 mo |

| Benoit et al[29] | 40 | 1 mo | 29 cm/4 kg | Ulceration, bleeding, infection | Yes | Benign PT/Adenofibroma or benign PT | Mastectomy/< 1 mm | Unknown |

| Our case | 42 | 2 mo | 30 cm/3.5 kg | Ulceration, bleeding, infection, Lung adenocarcinoma | Yes, suggested invasion | Malignancy not excluded/Benign PT | Mastectomy/< 1 mm | None for 12 mo |

An interesting fact about this case is our patient’s manifestations and imaging examinations led us to misdiagnose the mass as a malignant tumour. However pathological diagnosis of the tumour after complete excision confirmed it was a benign PT. Of the 12 cases of super-giant benign PTs diagnosed according to the postoperative pathology results, five cases were thought to be malignant tumours before surgery, accounting for almost one-half[1,3,6,8,12]. This finding shows that super-giant PTs may be more likely to reveal “malignant features”. Due to oversensitivity to ”malignant features”, excessive treatments were performed in these cases, including pectoral muscle excision[3,7,8,10], peripheral muscle excision[4], and lymph node sampling[5,7,8]. Most of the patients were stable without recurrence during the follow-up period. Only one patient died after 6 mo due to malignant pleural effusion; however, the patient had no prior history of lung disease and her breast tumour was a benign PT[7].

To avoid confusion regarding the diagnosis, and being misled by the atypical clinical presentation of the mass, and precisely differentiating benign from malignant PTs, it is more important to pay attention to the pathology results. Histologically, the lobulated structure is typical, and the mesenchymal cells in the lower epithelium undergo significant proliferation, which is helpful in the diagnosis of PT. According to World Health Organization recommendations, PTs can be classified into benign, borderline and malignant tumours depending on their histological features, including stromal hypercellularity, stromal atypia, mitosis, stromal overgrowth, and tumour margins (Table 2). Sometimes, the distinction between benign, borderline and malignant tumours may be particularly difficult from core biopsies, Dillon et al[5] reported that approximately 39% of false negative results were obtained. In addition, the mass was too large for the core needle biopsy to cover the entire area in our patient. Thus, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. One study by Kleer et al[6] showed that the Ki-67 labelling index was notably higher in high-grade malignant tumours compared to low-grade malignant tumours, and the Ki-67 labelling index in the low-grade malignant PT group was notably higher than that in the benign PT group (P = 0.012). P53 has also been used for distinction; however, both benign and malignant PTs show focally positive p53 occasionally. Bode et al[7] reported that p63, p40 and cytokeratin were only labelled in malignant tumours. Fibroadenomas, benign PTs, and borderline PTs are not labelled in this way. A study by Chia et al[8] revealed that cytokeratin can be focally positive in malignant tumours (1%-5%), which increases with PT grade. Another study found that p40 was more specific, but less sensitive, in distinguishing sarcomatoid carcinoma from malignant PT than p63, but this study requires further validation[11].

| Histologic features | Benign | Borderline | Malignant |

| Stromal hypercellularity | Mild | Moderate | Marked |

| Stromal mitotic activity | 0-4/10 HPF | 5-9/10 HPF | ≥ 10/10 HPF |

| Stromal cell atypia | Mild | Moderate | Marked |

| Stromal overgrowth | Absent | Absent or focal | Often present |

| Tumour borders | Well-defined | Well-defined focally infiltrative | Infiltrative |

| Malignant heterologous elements | Absent | Absent | May be present |

For primary treatment of PT, surgical resection is recommended. Previously, simple mastectomy was suggested for borderline and malignant PTs in order to reduce the recurrence rate. However, recent research has revealed that the survival after mastectomy and wide local excision with postoperative radiotherapy was equivalent[12]. Consequently, conservative surgery is recommended, but mastectomy should be carried out according to the following reasons: Benign or borderline tumours at least 8 cm in size, malignant PTs, or positive margins[13]. Margins of at least 1 cm with wide local excision were recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline for each PT grade. It is widely known that surgical margin status is an important risk factor for local recurrence. However, a meta-analysis demonstrated that margin positivity was a higher local recurrence (LR) risk only for malignant PTs, but was not associated with benign and borderline PTs[14]. In our case with a benign PT without distant metastasis, mastectomy was the better choice due to the large size of the tumour. The other 11 cases with huge benign PTs also underwent mastectomy. If the tumour size is less than 20 cm, wide local excision with a margin of at least 1 cm is preferred as the initial treatment. Lymph node metastasis is rare in PTs[2]. It is not necessary to routinely dissect axillary lymph nodes. However, sentinel lymph node biopsy or low-grade axillary lymph node dissection is recommended if palpable lymph nodes are detected pathologically[15]. After mastectomy for giant benign PTs, some cases chose reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap, or skin grafting. The study by Kuo et al[16] revealed that, for initial unresectable giant PTs, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization prior to surgery is recommended to improve the resectability of PTs without requiring skin grafting. In addition, postoperative chemotherapy and endocrine therapy have no significant effect on PTs, especially with regard to reducing the rate of recurrence or death.

According to a meta-analysis which included 9234 cases, the pooled LR rates for benign, borderline and malignant PTs were 8%, 13% and 18%, respectively, and the ranges of the 5-year cumulative LR risks for benign, borderline and malignant PTs were 3%-23%, 9%-55% and 14.8%-55%, respectively[14]. Other risk factors for LR also include mitoses, tumour border, stromal cellularity, stromal atypia, stromal overgrowth, tumour necrosis, and type of surgery. Another study revealed that patients without MED12 mutations had a higher likelihood of recurrence, whereas the disease-free survival of patients with PTs was improved with the occurrence of MED12 mutations[17]. Compared to the primary tumour, some studies have shown that similar or lower histological grading may occur during recurrences[18]. However, other studies have shown that the primary benign PT recurred as a malignant lesion[18,19]. For malignant PTs, the most common sites of metastasis included the lung (70% to 80%), pleura (60% to 70%), and bone (20% to 30%)[20].

PT is a rare fibroepithelial breast tumour. We report the unique case of a female patient who presented with a rapidly expanding breast PT. This case shows that a giant benign PT may reveal malignant features. The clinical manifestations and imaging examinations led us to misdiagnose the tumour as malignant. However, pathological diagnosis of the tumour after complete excision confirmed that it was a benign PT. Pathological and immunohistochemical results are important to differentiate this disease, and the lung nodule proved to be adenocarcinoma, rather than a metastatic tumour. These results are a reminder that we should not be fooled by appearances. All conditions should be considered to make an accurate diagnosis, in order that patients receive appropriate treatment and avoid excessive treatment[20-29].

We would like to thank Dr. Xiao-Song Chen (Ruijin Hospital) for additional editorial assistance.

| 1. | Krings G, Bean GR, Chen YY. Fibroepithelial lesions; The WHO spectrum. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:438-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lenhard MS, Kahlert S, Himsl I, Ditsch N, Untch M, Bauerfeind I. Phyllodes tumour of the breast: clinical follow-up of 33 cases of this rare disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;138:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tan PH, Thike AA, Tan WJ, Thu MM, Busmanis I, Li H, Chay WY, Tan MH; Phyllodes Tumour Network Singapore. Predicting clinical behaviour of breast phyllodes tumours: a nomogram based on histological criteria and surgical margins. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Islam S, Shah J, Harnarayan P, Naraynsingh V. The largest and neglected giant phyllodes tumor of the breast-A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dillon MF, Quinn CM, McDermott EW, O'Doherty A, O'Higgins N, Hill AD. Needle core biopsy in the diagnosis of phyllodes neoplasm. Surgery. 2006;140:779-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kleer CG, Giordano TJ, Braun T, Oberman HA. Pathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of benign and malignant phyllodes tumors of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:185-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bode MK, Rissanen T, Apaja-Sarkkinen M. Ultrasonography and core needle biopsy in the differential diagnosis of fibroadenoma and tumor phyllodes. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:708-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chia Y, Thike AA, Cheok PY, Yong-Zheng Chong L, Man-Kit Tse G, Tan PH. Stromal keratin expression in phyllodes tumours of the breast: a comparison with other spindle cell breast lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barrio AV, Clark BD, Goldberg JI, Hoque LW, Bernik SF, Flynn LW, Susnik B, Giri D, Polo K, Patil S, Van Zee KJ. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of 293 phyllodes tumors of the breast. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2961-2970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mishra SP, Tiwary SK, Mishra M, Khanna AK. Phyllodes tumor of breast: a review article. ISRN Surg. 2013;2013:361469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cimino-Mathews A, Sharma R, Illei PB, Vang R, Argani P. A subset of malignant phyllodes tumors express p63 and p40: a diagnostic pitfall in breast core needle biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1689-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barth RJ, Wells WA, Mitchell SE, Cole BF. A prospective, multi-institutional study of adjuvant radiotherapy after resection of malignant phyllodes tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2288-2294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang Y, Zhang Y, Chen G, Liu F, Liu C, Xu T, Ma Z. Huge borderline phyllodes breast tumor with repeated recurrences and progression toward more malignant phenotype: a case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:7787-7793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lu Y, Chen Y, Zhu L, Cartwright P, Song E, Jacobs L, Chen K. Local Recurrence of Benign, Borderline, and Malignant Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:1263-1275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parker SJ, Harries SA. Phyllodes tumours. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:428-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kuo CY, Lin SH, Lee KD, Cheng SJ, Chu JS, Tu SH. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization improves the resectability of malignant breast phyllodes tumor with angiosarcoma component: a case report. BMC Surg. 2019;19:100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ng CC, Tan J, Ong CK, Lim WK, Rajasegaran V, Nasir ND, Lim JC, Thike AA, Salahuddin SA, Iqbal J, Busmanis I, Chong AP, Teh BT, Tan PH. MED12 is frequently mutated in breast phyllodes tumours: a study of 112 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:685-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Borhani-Khomani K, Talman ML, Kroman N, Tvedskov TF. Risk of Local Recurrence of Benign and Borderline Phyllodes Tumors: A Danish Population-Based Retrospective Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1543-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Muller KE, Tafe LJ, de Abreu FB, Peterson JD, Wells WA, Barth RJ, Marotti JD. Benign phyllodes tumor of the breast recurring as a malignant phyllodes tumor and spindle cell metaplastic carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:327-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miyaguni T, Deguchi S, Teruya J, Kuniyoshi S, Tomita S, Soda N, Muto Y. Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast with a Grossly Malignant Appearance: A Case Report. Breast Cancer. 1998;5:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Udapudi DG, Vasudeva P, Srikantiah R, Virupakshappa E. Massive benign phyllodes tumor. Breast J. 2005;11:521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liang MI, Ramaswamy B, Patterson CC, McKelvey MT, Gordillo G, Nuovo GJ, Carson WE. Giant breast tumors: surgical management of phyllodes tumors, potential for reconstructive surgery and a review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhao Z, Zhang J, Chen Y, Shen L, Wang J. An 11 kg Phyllodes tumor of the breast in combination with other multiple chronic diseases: Case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:150-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Likhitmaskul T, Asanprakit W, Charoenthammaraksa S, Lohsiriwat V, Supaporn S, Vassanasiri W, Sattaporn S. Giant benign phyllodes tumor with lactating changes in pregnancy: a case report. Gland Surg. 2015;4:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sbeih MA, Engdahl R, Landa M, Ojutiku O, Morrison N, Depaz H. A giant phyllodes tumor causing ulceration and severe breast disfigurement: case report and review of giant phyllodes. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;2015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yan Z, Gudi M, Lim SH. A large benign phyllodes tumour of the breast: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;39:192-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kallam AR, Kanumury V, Korumilli RM, Gudeli V, Polavarapu H. Massive Benign Phyllodes Tumour of Breast Complicating Pregnancy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:PD08-PD09. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rathore AH. Huge Fungating Benign Phyllodes Tumor of Breast. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34:770-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Benoit L, Ilenko A, Chopier J, Buob D, Darai E, Zilberman S. A rare case of a giant ulcerated benign phyllode tumor. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rosenberger LH S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH