Published online Aug 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3573

Peer-review started: May 28, 2020

First decision: July 3, 2020

Revised: July 16, 2020

Accepted: August 1, 2020

Article in press: August 1, 2020

Published online: August 26, 2020

Processing time: 88 Days and 20.5 Hours

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is more common in young adults, usually caused by external factors like trauma. It causes symptoms such as chest pain or dyspnea, but it is rare to see elderly patients who develop SPM. Here we report the case of an elderly patient diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) who neither got mechanical ventilation nor had chest trauma but were found to develop SPM for unknown reason.

A 62-year-old man complained of a 14-d history of fever accompanied by dry cough, shortness of breath, wheezing, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting. Real-time fluorescence polymerase chain reaction confirmed the diagnosis of COVID-19. The patient was treated with supplementary oxygen by nasal cannula and gamma globulin. Other symptomatic treatments included antibacterial and antiviral treatments. On day 4 of hospitalization, he reported sudden onset of dyspnea. On day 6, he was somnolent. On day 12, the patient reported worsening right-sided chest pain which eventually progressed to bilateral chest pain. He was diagnosed with SPM, with no clear trigger found. Conservative treatment was administrated. During follow-up, the pneumomediastinum had resolved and the patient recovered without other complications.

We presume that aging lung changes and bronchopulmonary infection play an important part in the onset of SPM in COVID-19, but severe acute respiratory syndrome may represent a separate pathophysiologic mechanism for pneumomediastinum. Although the incidence of SPM in elderly patients is low, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of SPM in those infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 for life-threatening complications such as cardiorespiratory arrest may occur.

Core tip: The occurrence of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in coronavirus disease 2019 patients shows an ominous sign and should be taken into consideration even the patient’s age does not fit the stereotype of pneumomediastinum patients. The aging lung changes and bronchopulmonary infection can be the causes.

- Citation: Kong N, Gao C, Xu MS, Xie YL, Zhou CY. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in an elderly COVID-19 patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(16): 3573-3577

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i16/3573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3573

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is defined as the presence of interstitial air in the mediastinum that occurs without external factors such as blunt trauma or mechanical ventilation. The immediate pathophysiology can be explained by the Macklin effect, wherein an increased intrathoracic pressure results in the rupture of terminal alveoli and dissection of air along the tracheobronchial tree[1]. Precipitating factors include asthma, intense physical activity, and Valsalva manoeuvres (coughing, sneezing, and vomiting)[2]. The primary symptoms include chest pain with radiation to the back or neck, dysphonia, dyspnea, but sometimes can also be subtle. Other etiologies requiring differential diagnosis typically include cardiac tamponade, dissecting aortic aneurysm, and pulmonary embolism[3]. Computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard for the diagnosis as the anatomical visualization of the free air is evident on cross-sectional imaging[4]. Since pneumomediastinum itself is a self-limiting disease, in most conditions, it can resolve with conservative management such as analgesia, rest, and oxygen therapy.

However, things can be totally different when encountering coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This highly contagious viral pneumonia, which can eventually lead to respiratory failure, has currently caused a worldwide panic. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment strategies for these patients should be more careful. Interestingly, we identified an elderly patient who developed SPM during his course. SPM was predominantly seen in young men, pregnant women, or those with a history of asthma[5], not the elderly group. Here we report such case and give possible explanations from the geriatrics perspective.

A 62-year-old man presented with a 14-d history of fever.

He had a 14-d history of fever accompanied by dry cough, wheezing, nausea, and vomiting. His symptoms were exacerbated by exertion but the cause of the above symptoms was unknown. He seemed uncomfortable and anxious at the time of presentation. On day 4 of hospitalization, the patient reported sudden onset of dyspnea. On day 6, the patient was somnolent, and methylprednisolone was given. On day 12, the patient reported worsening right-sided chest pain, which eventually progressed to bilateral chest pain, and he was diagnosed with SPM with no clear trigger.

His past medical history included bronchitis and allergies to penicillin and cephalosporin.

The patient had no remarkable personal and family history.

At the time of admission, the patient’s vital sign parameters included a blood pressure of 110/65 mmHg, heart rate of 84 beats per minute, temperature of 39 ˚C, and blood oxygen saturation of 95%. Coarse breath sounds were heard in bilateral lungs.

At the time of admission, real-time fluorescence polymerase chain reaction was used to confirm the diagnosis of COVID-19.

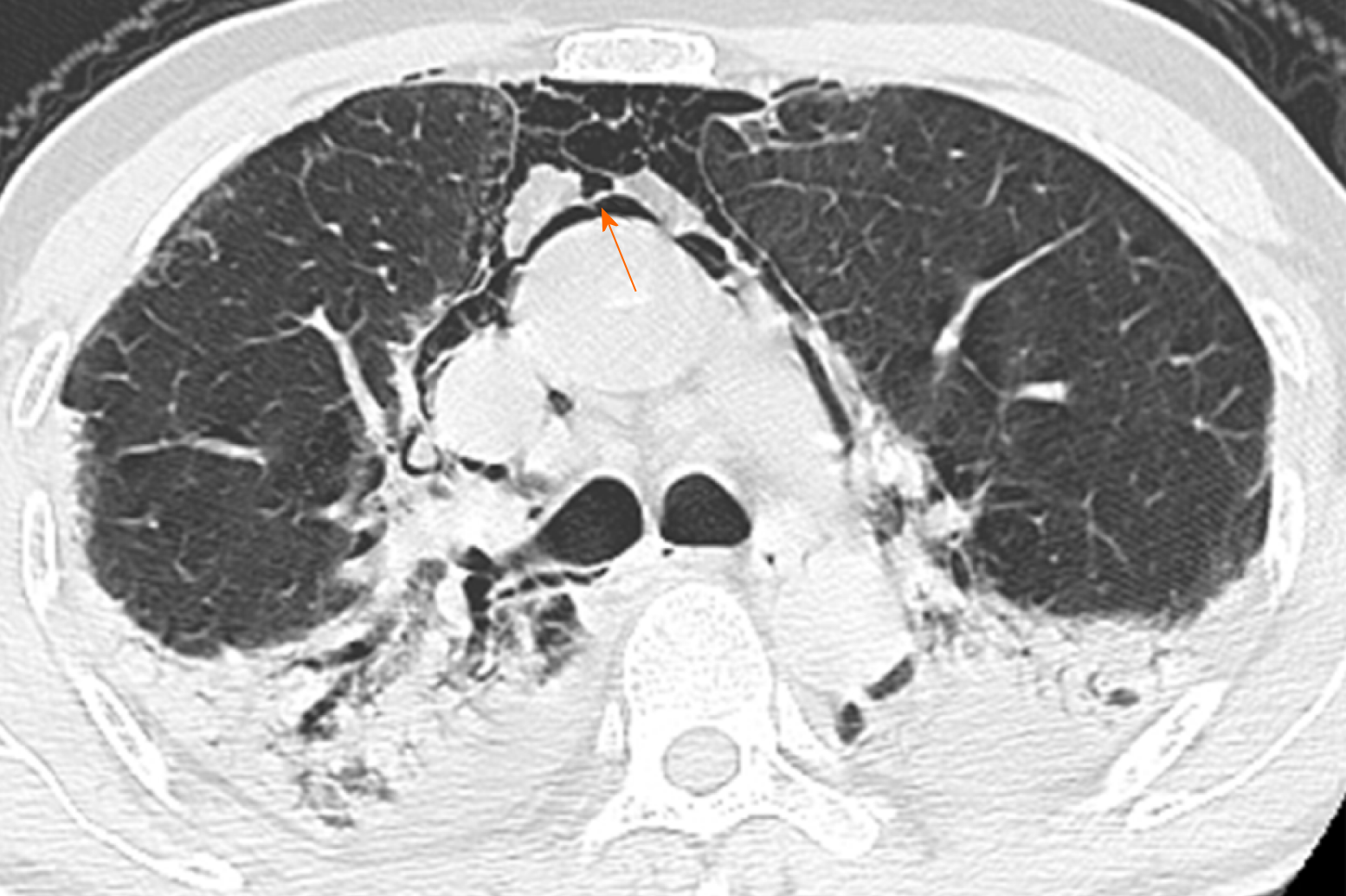

Initial chest CT showed multiple ground-glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening at the time of his admission. On day 12, after he complained of worsening chest pain, chest CT showed parenchymal consolidation and scattered pneumomediastinum (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 complicated with SPM.

The patient was treated with supplementary oxygen by nasal cannula (10 L/min) and gamma globulin 10 g/d. Other symptomatic treatments included antibacterial and antiviral treatments at the time of admission. Hexadecadrol 10 mg/d, doxofylline 0.2 g/d, and nikethamide were administered along with oxygen by non-rebreather mask at 10 L/min after the patient complained of sudden onset of dyspnea on day 4 of hospitalization, and methylprednisolone 20 mg/d was given after the patient developed somnolence. Conservative treatments were administrated for the sudden onset of SPM on day 12 (Table 1).

| February 2 | February 5 | February 7 | February 13 | |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, wheezing, nausea, womiting | Dyspnea | Somnolence | Worsening chest pain |

| Treatments | Supplementary oxygen, gamma globulin, antibacterial and antiviral treatments | Hexadecadrol,doxofylline, and nikethamide were added | Methylprednisolone was added | Conservative treatments |

| Chest CT | Multiple ground glass opacities with interlobular septal thickening | Parenchymal consolidation, scattered pneumomediastinum |

During follow-up, the pneumomediastinum had resolved and the patient recovered without other complications.

SPM is more common in young patients, especially in those who do intensive sports or have a medical history of asthma. Our patient is elderly and his age did not fit the stereotype of pneumomediastinum patients. He neither received mechanical ventilation nor had chest trauma, so the underlying mechanism deserves consideration. Although it is still unclear why he developed SPM, we have several speculations that may explain this phenomenon.

For elderly patients, the association between aging and the respiratory system should be considered first. Lung function decreases with age, and the decreased lung elastic recoil and increased residual volume in alveoli may contribute to the pressure gradient that results in rupture[6]. On the basis of aging lung changes, broncho-pulmonary infection is also a risk factor for we have found several papers that have also reported pneumomediastinum in conjunction with other pulmonary infections. Pneumomediastinum can be found in patients with AIDS presenting with community-acquired pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jirovecii[7]. Separately, Hasegawa et al[8] showed two children infected with the flu virus of H1N1 who developed SPM. Another elderly patient diagnosed with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) presenting as recurrent chest pain and reversible electrocardiography changes was also found to develop pneumomediastinum though she had weaned from ventilatory support[9]. Autopsy results from COVID-19 patients commonly show bilateral, diffuse alveolar damage and interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates[10], suggesting the effect of infection. In addition to the damage caused by infection, the increase in intrathoracic pressure caused by coughing and vomiting during the course of viral pneumonia may also have a role in the development of SPM .

It is worth mentioning that though SARS shares great similarities in clinical symptoms to COVID-19 and its pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) also belongs to the coronaviridae family, the incidence of SPM among patients with SARS was significantly higher (11.6%), as revealed by a study in Hong Kong[11], suggesting a separate pathophysiologic mechanism for pneumomediastinum. In the context of pathogenic mechanisms, SARS-CoV-2 has been found to have a lower pathogenicity than SARS-CoV due to the different efficiency of using angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors and the mutation of proteins[12], which may help to explain the different ratios of developing SPM.

Typically, pneumomediastinum is considered to be a treatable entity. However, the aging respiratory system is more fragile when facing diseases. Pneumomediastinum mimicking acute coronary syndrome would be misdiagnosed without imaging examination. The occurrence of SPM shows an ominous sign that the pneumonia may get worse. For elderly patients, SPM may be missed for some of them can just show subtle clinical findings including sore throat or neck pain. But if treated inappropriately, life-threatening complications such as tension pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax can occur, which finally leads to cardiorespiratory arrest[13]. As COVID-19 has become a worldwide pandemic, there is growing evidence about clinical presentation of this disease: Spontaneous pneumothorax had also been identified to be possible extrapulmonary complications in addition to pneumome-diastinum[14]. In individuals with co-morbid diseases, rupture typically indicates a poor prognosis. As such, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of SPM when treating elderly patients with COVID-19 complaining of chest discomfort such as pain, voice change, or dyspnea even though their ages do not fit the stereotype of SPM patients. Chest radiography or CT should be utilized immediately to investigate the suspected diagnosis. Pneumomediastinum itself is a self-limiting disease, and in most conditions it resolves with conservative management such as analgesia, rest, and oxygen therapy. But for elderly patients, hospitalization and aggressive approach should be taken into consideration if necessary.

Though rare, SPM still should be considered in elderly patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 for their cardio-pulmonary function is weaker than that of young adults.

| 1. | Cools B, Plaskie K, Van de Vijver K, Suys B. Unsuccessful resuscitation of a preterm infant due to a pneumothorax and a masked tension pneumopericardium. Resuscitation. 2008;78:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, Morera R, Escobar I, Saumench J, Perna V, Rivas F. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Langwieler TE, Steffani KD, Bogoevski DP, Mann O, Izbicki JR. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, Weiman D, Garrett HE. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:962-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Natale C, D'Journo XB, Duconseil P, Thomas PA. Recurrent spontaneous pneumomediastinum in an adult. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:1199-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rossi A, Ganassini A, Tantucci C, Grassi V. Aging and the respiratory system. Aging (Milano). 1996;8:143-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheng WL, Ko WC, Lee NY, Chang CM, Lee CC, Li MC, Li CW. Pneumomediastinum in patients with AIDS: a case report and literature review. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;22:31-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hasegawa M, Hashimoto K, Morozumi M, Ubukata K, Takahashi T, Inamo Y. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating pneumonia in children infected with the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Tse TS, Tsui KL, Yam LY, So LK, Lau AC, Chan KK, Li SK. Occult pneumomediastinum in a SARS patient presenting as recurrent chest pain and acute ECG changes mimicking acute coronary syndrome. Respirology. 2004;9:271-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhao P, Liu H, Zhu L, Tai Y, Bai C, Gao T, Song J, Xia P, Dong J, Zhao J, Wang FS. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5228] [Cited by in RCA: 5838] [Article Influence: 973.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 11. | Chu CM, Leung YY, Hui JY, Hung IF, Chan VL, Leung WS, Law KI, Chan CS, Chan KS, Yuen KY. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:802-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu J, Zhao S, Teng T, Abdalla AE, Zhu W, Xie L, Wang Y, Guo X. Systematic Comparison of Two Animal-to-Human Transmitted Human Coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Viruses. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 71.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Newcomb AE, Clarke CP. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest. 2005;128:3298-3302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | López Vega JM, Parra Gordo ML, Diez Tascón A, Ossaba Vélez S. Pneumomediastinum and spontaneous pneumothorax as an extrapulmonary complication of COVID-19 disease. Emerg Radiol. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Mattioli AV S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ