Published online Jul 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.2950

Peer-review started: May 21, 2020

First decision: June 4, 2020

Revised: June 14, 2020

Accepted: July 1, 2020

Article in press: July 1, 2020

Published online: July 26, 2020

Processing time: 64 Days and 8.1 Hours

A large number of pneumonia cases due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been first reported in China. Meanwhile, the virus is sweeping all around the world and has infected millions of people. Fever and pulmonary symptoms have been noticed as major and early signs of infection, whereas gastrointestinal symptoms were also observed in a significant portion of patients. The clinical investigation of disease onset was underestimated, especially due to the neglection of cases presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms.

To characterize the clinical features of coronavirus-infected patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms.

This is a retrospective, single-center case series of the general consecutive hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 at Wuhan Union Hospital from February 2, 2020 to February 13, 2020. According to their initial symptoms, these patients were classified into two groups. Patients in group one presented with pulmonary symptoms (PS) as initial symptoms, and group two presented with gastrointestinal symptoms (GS). Epidemiological, demographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment data were collected for analysis.

Among the 50 patients recruited, no patient has been admitted to intensive care units, and no patient died during the study. The duration of hospitalization was longer in the GS group than in the PS group (12.13 ± 2.44 vs 10.00 ± 2.13, P < 0.01). All of the 50 patients exhibited decreased lymphocytes. However, lymphocytes in the GS group were significantly lower compared to those in the PS group (0.94 ± 0.06 vs 1.04 ± 0.15, P < 0.01). Procalcitonin and hs-CRP were both significantly higher in the GS group than in the PS group. Accordingly, the duration of viral shedding was significantly longer in the GS group compared to the PS group (10.22 ± 1.93 vs 8.15 ± 1.87, P < 0.01).

COVID-19 patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms need more days of viral shedding and hospitalization than the patients presenting with pulmonary symptoms.

Core tip: The objective of this retrospective case series was to characterize the clinical features of coronavirus-infected patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms. The clinical investigation of disease onset was underestimated, especially due to the neglection of cases presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms. We aimed to address this issue and provide an insight into the different initial symptoms between the pulmonary symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms. Coronavirus disease 2019 patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms need more days of viral shedding and hospitalization than the patients presenting with pulmonary symptoms.

- Citation: Yang TY, Li YC, Wang SC, Dai QQ, Jiang XS, Zuo S, Jia L, Zheng JB, Wang HL. Clinical characteristics of patients with COVID-19 presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms: Retrospective case series. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(14): 2950-2958

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i14/2950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i14.2950

A staggering number of pneumonia cases caused by a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) are being confirmed globally[1]. As of May 2, 2020, 82877 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases have been confirmed in China with 4633 deaths being reported. Meanwhile, the virus is still sweeping the world and has infected millions of people[2]. According to recent publications[3], the most common initial symptoms in COVID-19 patients have been recognized as pulmonary symptoms, such as fever, cough, and expectoration. However, gastrointestinal symptoms were also observed in a significant portion of patients[4,5]. In addition, recent studies have shown that the receptor of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is essential for cells to be infected by the 2019-nCoV, is highly expressed not only on AT2 cells from the lungs but also on absorptive enterocytes from the ileum and colon[6]. The clinical investigation of disease onset was underestimated at the beginning, especially on gastrointestinal symptoms.

To gain an insight into the different initial symptoms of both pulmonary and gastrointestinal categories, determine the clinical characteristics of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, and to compare outcomes of patients presenting with different initial symptoms, we collected data from the west campus of Wuhan Union Hospital for further investigation.

We conducted a retrospective study aiming to investigate the clinical characteristics of mild COVID-19 cases admitted to the west campus of Wuhan Union Hospital (from February 2nd 2020 to February 13th 2020). Due to urgent circumstances, this study was authorized by the Ethics Commission of Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (KY2020-007) and orally authorized by Wuhan Union Hospital. The diagnosis of mild COVID-19 was based on the following criteria[7]: (1) Identification of 2019-nCoV via RT-PCR in nasopharyngeal swab samples; and (2) Fulfilling the conditions of respiratory distress (< 30 times/min), oxygen saturation at rest > 93%, and arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspiration O2 (FiO2) > 300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa). According to survey and investigation, none of the infected patients have ever been exposed to Huanan Seafood Market, which has been regarded as the original source of the virus. All recruited cases were infected by human-to-human transmission. These patients have been classified into two groups according to their initial symptoms. One group exhibited pulmonary symptoms (PS) as their initial symptoms, such as fever, cough, and expectoration, while the other group presented gastrointestinal symptoms (GS) as their initial symptoms, such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.

Every general patient was prescribed with the same drug recipe: Oral intake of 200 mg Arbidol three times a day. The discharge of general patients with COVID-19 must meet the criteria under the following conditions: (1) Body temperature have been returned to normal range for over 3 d; (2) Respiratory symptoms get improved significantly; (3) Acute exudative lesions once exhibited on pulmonary imaging have been significantly improved; and (4) Nucleic acid test of sputum, nasopharyngeal swab, and other respiratory samples showed negative results for two separate RT-PCR tests which were taken 24 h apart.

Subjects would be included in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) Aged 18 years old or above; and (2) Confirmed as general COVID-19.

Subjects would be excluded from this study if they met the following criteria: (1) Allergic or intolerat to any of the therapeutic drugs (Arbidol) used in this study; (2) Pregnant or lactating women; and (3) Presence of severe systemic illness that may affect the efficacy or safety evaluation for this study.

Epidemiological, clinical, laboratorial, and radiological characteristics, together with treatment and outcome information were obtained by filling out data collection forms according to electronic medical records. The date of disease onset was defined as the day when symptoms were noticed. Symptoms, laboratory tests, chest CT scan, and therapeutic measures during hospitalization were summarized. Sputum and throat swab specimens collected from all patients at admission were tested by RT-PCR for 2019-nCoV RNA within 3 h. Virus detection was repeated every 24 h.

For categorical variables, we calculated the percentages of patients in each category. Means for continuous variables were compared using independent group t tests when data were normally distributed; otherwise, Mann-Whitney test was performed. Proportions for categorical variables were compared using χ2 test. All analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 22.0. And P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The characteristics of the 50 recruited patients (27 presented with PS vs 23 presented with GS) are summarized in Table 1. Data included age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities (hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic liver disease), oxygenation index, mean arterial pressure, and time from symptoms onset to hospital admission (days). No significant differences were observed between the two groups for the abovementioned factors. The duration of hospitalization was significantly longer in the GS group compared to the PS group (12.13 ± 2.44 vs 10.00 ± 2.13, P < 0.01). The duration of viral shedding was significantly longer in the GS group compared to the PS group (10.22 ± 1.93 vs 8.15 ± 1.87, P < 0.01). The temperature tested on admission was significantly higher in the GS group than in the PS group (37.00 ± 2.67 vs 37.19 ± 2.67, P < 0.01). Moreover, the percentage of smokers was higher in the GS group than in the PS group. And the patients in the GS group needed more nasal cannula treatment compared to the PS group.

| Parameter | PS group | GS group | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (yr) | 42.47 ± 3.25 | 44.56 ± 2.78 | -0.02 | 0.98 |

| Gender (%) | 0.01 | 0.94 | ||

| Female | 12 (44.4) | 10 (43.5) | ||

| Male | 15 (55.6) | 13 (56.5) | ||

| BMI | 23.56 ± 1.78 | 23.82 ± 1.63 | -0.68 | 0.61 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 1 | 2 | 0.55 | 0.46 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| COPD | 2 | 1 | 0,21 | 0.65 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Oxygenation index | 352.56 ± 12.63 | 348.72 ± 11.67 | 0.61 | 0.56 |

| Mean arterial pressure | 78.56 ± 3.65 | 76.34 ± 2.96 | -0.56 | 0.58 |

| Time from symptoms onset to hospital admission (d) | 3.62 ± 1.23 | 3.78 ± 1.36 | 0.35 | 0.74 |

| Days of viral shedding | 8.15 ± 1.87 | 10.22 ± 1.93 | -3.25 | 0.01a |

| Duration days | 10.00 ± 2.13 | 12.13 ± 2.44 | -3.22 | 0.01a |

| Smokers (%) | 8 (29.6) | 14 (60.9) | 4.92 | 0.03a |

| Temperature on admission | 37.00 ± 2.67 | 37.19 ± 2.67 | -2.42 | 0.02a |

| Treatment in hospital | 4.06 | 0.04a | ||

| Nasal cannula | 3 | 8 | ||

| No nasal cannula | 24 | 15 | ||

Laboratory identifications based on 50 patients are summarized in Table 2. All 50 patients in the two groups have been tested for hematologic, biochemical, and infection-related indices, together with coagulation function examination on admission. All of the 50 patients exhibited decreased lymphocytes. Moreover, lymphocytes in the GS group patients were significantly lower compared to the PS group (0.94 ± 0.06 vs 1.04 ± 0.15, P < 0.01). In addition, prealbumin was significantly lower in the GS group compared to the PS group (123.70 ± 6.17 vs 127.63 ± 7.03, P < 0.05). For infection-related indices, procalcitonin and hs-CRP were both significantly higher in the GS group than in the PS group. For coagulation functions, prothrombin time and D-dimer were both significantly higher in the GS group. Prealbumin below normal level was linked to longer hospitalization. However, procalcitonin and D-dimer above normal were related to longer duration days.

| PS group | GS group | t/χ2 | P value | |

| White blood cells, × 109/mL | 6.32 ± 1.26 | 6.85 ± 1.37 | 0.62 | 0.55 |

| Lymphocytes, × 109/mL | 1.04 ± 0.15 | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 2.91 | 0.01a |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 122.37 ± 5.78 | 120 ± 6.32 | 0.73 | 0.67 |

| Platelet count, × 109/L | 212 ± 8.96 | 208 ± 7.45 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| AST, U/L | 31.45 ± 4.62 | 30.16 ± 3.98 | 0.66 | 0.59 |

| ALT, U/L | 30.57 ± 4.13 | 29.66 ± 4.02 | 0.82 | 0.75 |

| Prealbumin, mg/L | 127.63 ± 7.03 | 123.70 ± 6.17 | 2.10 | 0.04a |

| < 130 | 7 | 13 | 4.84 | 0.02a |

| > 130 | 20 | 10 | ||

| Albumin, g/L | 36.42 ± 3.65 | 36.12 ± 2.97 | 0.75 | 0.69 |

| Globulin, g/L | 25.42 ± 3.11 | 24.66 ± 2.92 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 4.12 ± 1.01 | 4.89 ± 0.96 | -1.98 | 0.57 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 68.71 ± 6.46 | 71.36 ± 5.4 | -2.03 | 0.42 |

| Glucose, mM | 5.99 ± 1.02 | 5.73 ± 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

| CK-MB, U/L | 18.44 ± 4.61 | 17.12 ± 3.89 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| LDH, U/L | 135.66 ± 6.41 | 133.96 ± 5.78 | 0.81 | 0.74 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | -2.82 | 0.01a |

| > 0.05 | 20 | 10 | 4.84 | 0.02a |

| < 0.05 | 7 | 13 | ||

| hs-CRP, mg/L | 54.70 ± 17.13 | 68.91 ± 19.08 | -2.77 | 0.01a |

| Prothrombin time, s | 13.23 ± 0.56 | 13.67 ± 0.52 | -2.87 | 0.01a |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 0.42 ± 0.11 | 0.56 ± 0.13 | -2.79 | 0.01a |

| < 0.5 | 17 | 8 | 3.95 | 0.04a |

| > 0.5 | 10 | 15 |

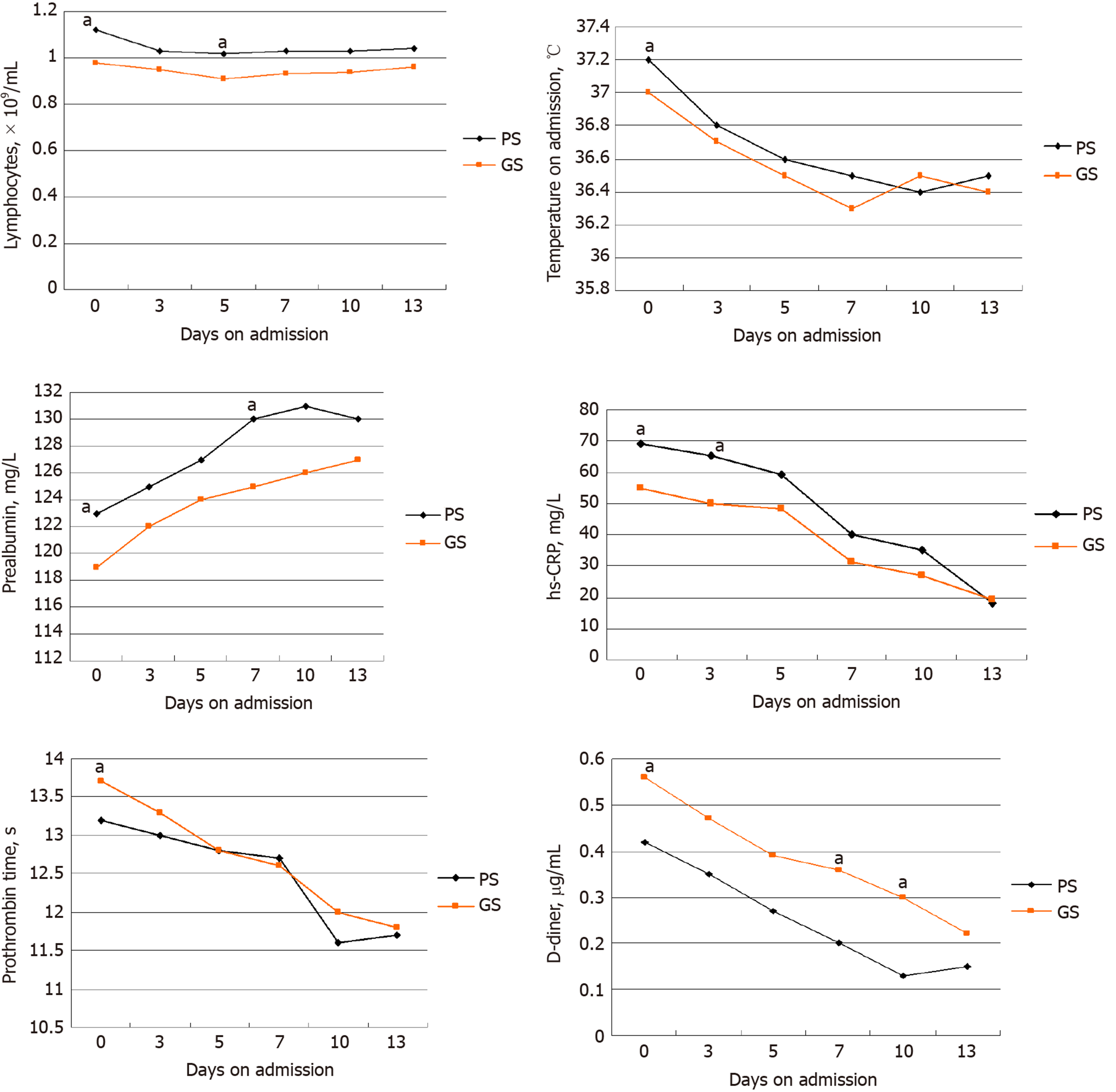

In order to record major clinical feature progressions that appeared during COVID-19, the dynamic changes in clinical laboratory parameters, including hematological and biochemical parameters, were tracked from the day of admission to day 13 at a 2-3 d interval. Data from the 50 patients with statistical differences in clinical course between two groups were analyzed (Figure 1). During hospitalization, most patients exhibited marked lymphopenia, while the GS group developed more severe lymphopenia over time. The levels of temperature compared to those tested on admission decreased quickly in the GS group. The GS group patients suffered more from undernutrition due to their lower prealbumin levels. Procalcitonin and hs-CRP were higher in the GS group compared to the PS group. The level of D-dimer and prothrombin time were higher in the GS group compared to the PS group.

It is well known that the respiratory tract accommodates its own microbiota, however, patients with respiratory infections are generally complicated with gut dysfunction or secondary gut dysfunction, which are related to a more severe clinical course depicted as gut-lung crosstalk[8]. This phenomenon could also be observed in general patients with COVID-19. Previous studies reported that there is a structural similarity between the receptor-binding domains of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and 2019-nCoV by molecular modeling[9]. Other receptors have also been uncovered, such as ACE2 receptor. ACE2 receptor is known to be abundantly expressed in humans in the epithelia of both the lung and intestine[10,11], which serves as evidence supporting that gastrointestinal route might be a possible route for 2019-nCoV infection[12]. The time for general COVID-19 patients to turn into viral nucleic acids negative result was affected in patients whose initial symptoms are gastrointestinal symptoms. Recent studies have demonstrated that modulating gut microbiota could reduce enteritis and ventilator-associated pneumonia, and it could reverse some side effects of antibiotics to avoid facilitating early influenza virus replication in lung epithelia[13]. We suggest that the human intestinal tract may serve as an alternative route for 2019-nCoV infection. In terms of the fact[14,15] that the first batch of patients who have correlations with a wild animal market during the beginning of the outbreak showed serious symptoms that resulted in a high mortality rate, gastrointestinal symptoms could have been underestimated. When infected patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms visit the gastroenterology clinic, the novel coronavirus may have already increased the pulmonary virus content through gut-lung crosstalk[16].

It has been recognized that ACE2 controls intestinal inflammation and causes diarrhea when SARS-CoV-2 load is high in the gastrointestinal region[17]. COVID-19 can disrupt the function of ACE2 and results in diarrhea. SARS-CoV-2 is highly homologous to SARS-CoV and about 20%-25% of SARS patients have diarrhea[18]. It is incomprehensible to notice the low incidence rate (5%–6%) of diarrhea in most cohorts from hospitals in Wuhan[19,20]. The underestimation may be due to the lack of a precise criterion for gastrointestinal symptoms. The definition of diarrhea released by the WHO is having three or more loose/liquid stools per day, or having more stools than a person’s health condition[21]. It may prompt us to assume that the patients whose initial symptoms belong to gastrointestinal type are more serious than other patients. Furthermore, when infected patients with diarrhea visit gastroenterology department, it may increase the risk of transmission to healthcare workers. Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms need longer time to recover from the disease. Most countries encounter the problem that the demand of viral nucleic acids test kits exceeds supply. Therefore, when patients with gastrointestinal type as initial symptoms are relieved, we should accordingly extend the frequency of nucleic acid detection, so that the consumption of the viral nucleic acid test kits can be controlled and well-arranged.

Accumulating efforts from Chinese government and boosting COVID-19 related research are ongoing since then. No specific antiviral treatment is recommended now. Considering the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor may determine the path of infection[22,23], therefore, the route of infection is essential for understanding pathogenesis process, both of which are of paramount importance for infection control in hospitals and society. We speculate that probiotics which could modulate gut microbiota to favorably improve gastrointestinal symptom may also exert respiratory protection. Further investigation could focus on this direction and it will be promising to study the benefits of gastrointestinal probiotics on pulmonary diseases, which might be realized via modulating gut-lung microbiota. At last, we call upon all first-line medical staff to be cautious and pay more attention to those patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial presentations. We hope that with collaborative efforts and huge support, the success of fighting COVID-19 pandemic will come soon.

Our study has three limitations. First, patient cases were limited as all from one hospital in Wuhan, which prevented that more clinical features related to initial presentations of gastrointestinal symptoms were characterized. Second, only 50 patients were included. Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial presentations had atypical symptoms, which only accounted for about 6% of patients in our research hospital. Third, we did not count up the number of the general patients who relapsed as viral nucleic acids positive after discharge, which might result in biases of clinical observation characteristics.

In this study, initial symptoms belonging to gastrointestinal type affect the time of general patients’ viral nucleic acids test turning negative. General COVID-19 patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms need more days of viral shedding and hospitalization compared to the patients presenting with pulmonary symptoms. Currently, no effective drug treatment or vaccine exists. It is necessary to improve the treatment of patients whose initial symptoms belong to gastrointestinal type.

A large number of pneumonia cases due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been first reported in China. Meanwhile, the virus is sweeping all around the world and has infected millions of people. Fever and pulmonary symptoms have been noticed as major and early signs of infection, whereas gastrointestinal symptoms were also observed in a significant portion of patients. The clinical investigation of disease onset was underestimated, especially due to the neglection of cases presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms.

We aimed to address this issue and provide an insight into the different initial symptoms between the pulmonary symptoms and gastrointestinal symptoms.

The objective of this case series study was to characterize the clinical features of coronavirus-infected patients with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms.

This is a retrospective, single-center case series of the general consecutive hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19 at Wuhan Union Hospital from February 2, 2020 to February 13, 2020. According to their initial symptoms, these patients were classified into two groups. Patients in group one presented with pulmonary symptoms (PS) as initial symptoms, and group two presented with gastrointestinal symptoms (GS). Epidemiological, demographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment data were collected for analysis.

Among the 50 patients recruited, no patient has been admitted to intensive care units, and no patient died during the study. The duration of hospitalization was longer in the GS group than in the PS group (12.13 ± 2.44 vs 10.00 ± 2.13, P < 0.01). All of the 50 patients exhibited decreased lymphocytes. However, lymphocytes in the GS group were significantly lower compared to those in the PS group (0.94 ± 0.06 vs 1.04 ± 0.15, P < 0.01). Procalcitonin and hs-CRP were both significantly higher in the GS group than in the PS group. Accordingly, the duration of viral shedding was significantly longer in the GS group compared to the PS group (10.22 ± 1.93 vs 8.15 ± 1.87, P < 0.01).

COVID-19 patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms as initial symptoms need more days of viral shedding and hospitalization than the patients presenting with pulmonary symptoms

In this study, initial symptoms belonging to gastrointestinal type affect the time of general patients’ viral nucleic acids test turning negative. Currently, no effective drug treatment or vaccine exists. It is necessary to improve the treatment of patients whose initial symptoms belong to gastrointestinal type.

We would like to thank all the medical staff and local authorities of Heilongjiang Province for their efforts in combating the outbreak of COVID-19.

| 1. | Zippi M, Fiorino S, Occhigrossi G, Hong W. Hypertransaminasemia in the course of infection with SARS-CoV-2: Incidence and pathogenetic hypothesis. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1385-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Souza Ferreira LP, Valente TM, Tiraboschi FA, da Silva GPF. Description of Covid-19 Cases in Brazil and Italy. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ji W, Wang W, Zhao X, Zai J, Li X. Cross-species transmission of the newly identified coronavirus 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 518] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 89.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30479] [Article Influence: 5079.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 5. | Peng M, Ren D, Liu XY, Li JX, Chen RL, Yu BJ, Liu YF, Meng X, Lyu YS. COVID-19 managed with early non-invasive ventilation and a bundle pharmacotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1705-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus Infections-More Than Just the Common Cold. JAMA. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1204] [Cited by in RCA: 1143] [Article Influence: 190.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Razai MS, Doerholt K, Ladhani S, Oakeshott P. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19): a guide for UK GPs. BMJ. 2020;368:m800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ma XP, Wang H, Bai DM, Zou Y, Zhou SM, Wen FQ, Dai DL. Prevention program for the COVID-19 in a children's digestive endoscopy center. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1343-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gao QY, Chen YX, Fang JY. 2019 Novel coronavirus infection and gastrointestinal tract. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:125-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 46.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4848] [Cited by in RCA: 4440] [Article Influence: 740.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Tian Y, Rong L, Nian W, He Y. Review article: gastrointestinal features in COVID-19 and the possibility of faecal transmission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:843-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 587] [Article Influence: 97.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lin L, Jiang X, Zhang Z, Huang S, Zhang Z, Fang Z, Gu Z, Gao L, Shi H, Mai L, Liu Y, Lin X, Lai R, Yan Z, Li X, Shan H. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69:997-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 663] [Article Influence: 110.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, Ma K, Xu D, Yu H, Wang H, Wang T, Guo W, Chen J, Ding C, Zhang X, Huang J, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2289] [Cited by in RCA: 2565] [Article Influence: 427.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Zhou Z, Zhao N, Shu Y, Han S, Chen B, Shu X. Effect of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2294-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liang W, Feng Z, Rao S, Xiao C, Xue X, Lin Z, Zhang Q, Qi W. Diarrhoea may be underestimated: a missing link in 2019 novel coronavirus. Gut. 2020;69:1141-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14113] [Cited by in RCA: 14869] [Article Influence: 2478.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, Wang H, Wan J, Wang X, Lu Z. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;e201017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2516] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 478.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Lin L, Lu L, Cao W, Li T. Hypothesis for potential pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection-a review of immune changes in patients with viral pneumonia. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:727-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 93.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, Tan YY, Chen SD, Jin HJ, Tan KS, Wang DY, Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1854] [Cited by in RCA: 2029] [Article Influence: 338.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yuen KS, Ye ZW, Fung SY, Chan CP, Jin DY. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 58.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhou M, Zhang X, Qu J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a clinical update. Front Med. 2020;14:126-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leng Z, Zhu R, Hou W, Feng Y, Yang Y, Han Q, Shan G, Meng F, Du D, Wang S, Fan J, Wang W, Deng L, Shi H, Li H, Hu Z, Zhang F, Gao J, Liu H, Li X, Zhao Y, Yin K, He X, Gao Z, Wang Y, Yang B, Jin R, Stambler I, Lim LW, Su H, Moskalev A, Cano A, Chakrabarti S, Min KJ, Ellison-Hughes G, Caruso C, Jin K, Zhao RC. Transplantation of ACE2- Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improves the Outcome of Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Aging Dis. 2020;11:216-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 730] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 143.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Qin YY, Zhou YH, Lu YQ, Sun F, Yang S, Harypursat V, Chen YK. Effectiveness of glucocorticoid therapy in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:1080-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Souza Ferreira LP S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH