Published online Jun 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2325

Peer-review started: April 9, 2020

First decision: April 29, 2020

Revised: May 16, 2020

Accepted: May 19, 2020

Article in press: May 19, 2020

Published online: June 6, 2020

Processing time: 59 Days and 11.9 Hours

Since December 2019, many cases of pneumonia caused by novel coronavirus have been discovered in Wuhan, China, and such cases have spread nationwide quickly. At present, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide pandemic. What are the clinical features of this disease? What is the clinical diagnosis and how should such patients be treated? As a clinician, mastery of the clinical characteristics, basic diagnosis, and treatment methods of COVID-19 are required to provide help to patients.

A 42-year-old male patient with a cough lasting 6 d without obvious cause, as well as fever and fatigue for 1 d, was admitted to Hankou Hospital on January 22, 2020 and transferred to Huoshenshan Hospital on February 4. The main clinical symptoms were dry cough, fatigue, and fever. He was diagnosed with COVID-19. From the 4th d of admission, the patient’s condition gradually worsened, with increased respiratory rate and body temperature. Peripheral blood lymphocytes decreased progressively. On the 8th d of admission, the patient’s highest temperature was 40.7 °C, and oxygen saturation was 83% despite high-flow oxygen inhalation. Chest computed tomography results showed that the virus progressed rapidly. The number of lesions significantly increased with expanded scope and increased density. The distribution of lesions advanced from peripheral to central. In addition to nasal catheter oxygen inhalation and symptomatic support, antiviral drugs were used throughout the treatment. On January 22, oseltamivir phosphate capsules were given orally (75 mg, twice daily) for 6 d. On January 24, three tablets of lopinavir and ritonavir were added orally (twice daily). After 6 d, this was changed to 0.2 g (two tablets) arbidol, taken orally (three times daily) for 5 d. During the severe stage, methylprednisolone was given (40 mg) once every 12 h, immunoglobulin (20 g) was administered by intravenous drip infusion once daily, and thymosin (1.6 mg) was injected subcutaneously once daily combined with immunotherapy. On February 2, symptoms decreased, various indicators improved, and pulmonary inflammation was obviously reduced. Throat swabs on February 4 and 9 were negative for novel coronavirus nucleic acid. After 19 d in the hospital, the patient was successfully treated and discharged.

COVID-19 in young adults can be successfully treated with active treatment. We report a typical case of COVID-19, analyze its clinical characteristics, summarize its clinical diagnosis and treatment experience, and provide a reference for clinical colleagues.

Core tip: A 42-year-old male patient with coronavirus disease 2019 was admitted to Hankou Hospital on January 22, 2020 and transferred to Huoshenshan Hospital on February 4. The main clinical symptoms were dry cough, fatigue, and fever. From the 4th d of admission, the patient's condition gradually worsened. A series of simultaneous active treatments (including general treatment such as oxygen inhalation and supportive treatment), antiviral treatment, glucocorticoid and combined immunotherapy were given. In the severe stage, methylprednisolone was given. The patient was successfully treated and discharged after 19 d in the hospital.

- Citation: He YF, Lian SJ, Dong YC. Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of COVID-19: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(11): 2325-2331

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i11/2325.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2325

Since December 2019, many cases of pneumonia infected-novel coronavirus have been found in Wuhan, Hubei Province[1]. With the spread of the epidemic, such cases have appeared in other areas of China and abroad. The novel coronavirus causing pneumonia was officially named “2019 novel coronavirus” (2019-nCoV) by the World Health Organization on January 12, 2020. The novel coronavirus pneumonia was named “COVID-19” by the World Health Organization on February 11, 2020. Meanwhile, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses named the new coronavirus “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)”[2]. Novel coronavirus pneumonia does not have a vaccine or effective antiviral. At present, after active treatment, an increasing number of patients have been successfully treated and discharged, with a mortality rate of about 3.2%[3]. In this paper, the clinical characteristics of a patient with COVID-19 who was successfully treated were analyzed, and the clinical experience was summarized to provide a reference for clinical colleagues.

A 42-year-old male patient had a cough for 6 d without obvious cause, as well as fever and fatigue for 1 d.

On January 16, 2020, the patient developed a cough with a small amount of white phlegm, which was not easy to cough up. He had no chest pain, dyspnea, palpitation, chest tightness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or other discomfort and was not treated. On January 22, he had a fever with a maximum temperature of 38.5°C, as well as pain, fatigue, and poor appetite. He was admitted to Wuhan Hankou hospital for treatment on the same day after self-treatment. On February 4, he was transferred to Huoshenshan Hospital for treatment.

The patient’s body temperature was 36.8°C, pulse was 85/min, breath was 20/min, and blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg on the day of admission. His mind and spirit were normal, and his superficial lymph nodes were not swollen. Breathing in both lungs sounded thick, but there were no obvious dry or wet rales. Cardiac auscultation revealed no abnormalities. The abdomen was flat and soft. He did not have lumps, tenderness, or rebound pain. Limb muscle strength was normal, and pathological signs were negative.

The patient was a medical worker in Wuhan, where he had lived for a long time, with a history of living in the epidemic area. He had contact with many fever patients before getting sick himself.

The patient had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or other systemic diseases.

The patient did not smoke or have other risk factors. His wife and family members were healthy.

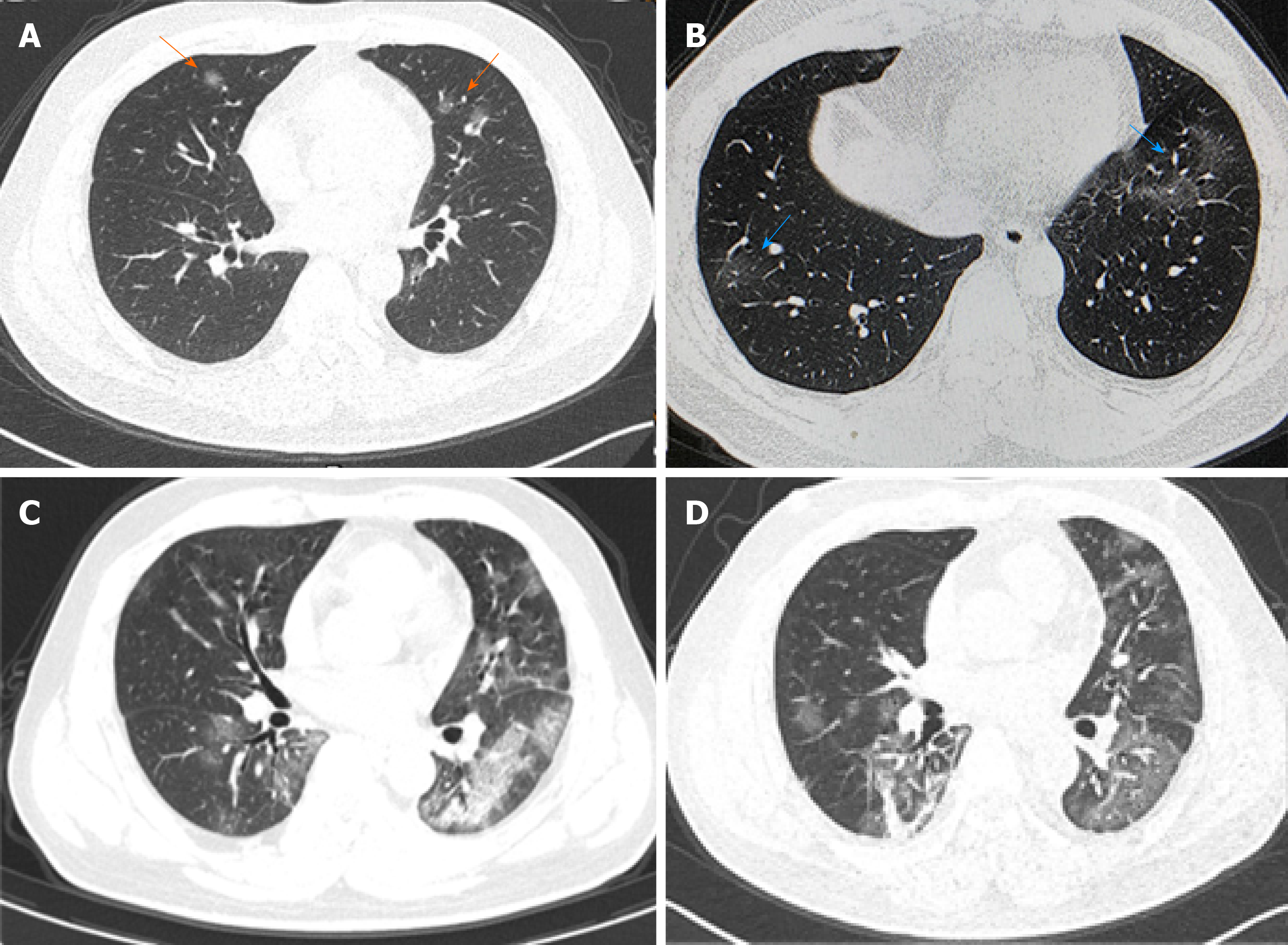

On January 22, the patient’s blood routine examination showed that the leukocyte count was 4.3×109/L, lymphocyte count was 1.2×109/L, procalcitonin (PCT) was 0.11 ng/mL, hypersensitive c-reactive protein (hsCRP) was 3.39 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 8.81 mm/h. Oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 98% (air absorption). A chest computed tomography (CT) examination revealed a small amount of ground-glass exudation in both lungs (Figure 1A). A throat swab tested positive for the nucleic acid of 2019-nCoV.

According to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (revised version 5th) issued by the General Office of National Health Commission, the patient was diagnosed as having COVID-19[4].

On January 22, oseltamivir phosphate capsules were given orally twice daily for 6 d; 40 mg methylprednisolone with 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution was given intravenously once daily; 0.4 g moxifloxacin with 100 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution was given intravenously once daily; 3 g cefoperazone with 100 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution was given intravenously once every 12 h.

On January 24, the body temperature fluctuated between 37 and 38 °C, and there was no significant change in other symptoms. Lopinavir and ritonavir tablets were given orally (3 tablets, twice daily, for 6 d). Chest distress and shortness of breath occurred on January 26. SpO2 was 94% (oxygen intake flow was 3 L/min). Another chest CT showed that the exudation increased compared with that before (Figure 1B). Antibiotics were stopped, and other treatments were not adjusted.

On January 28, the highest body temperature was 38.4 °C, respiratory rate was 28/min, and SpO2was 93% (oxygen intake flow was 5 L/min). Blood lymphocyte count was 0.7 × 109/L, hsCRP was 19.4 mg/L, PCT was 0.087 ng/mL, and ESR was 44.2 mm/h. Human immunoglobulin (intravenous drip, 10 g once daily) was added to the treatment. On January 29, the body temperature was normal but dyspnea had not improved. Lopinavir and ritonavir tablets were stopped and changed to 0.2 g arbidol (two tablets), taken orally three times daily for 5 d.

On January 30, the patient’s progress was as follows: Body temperature was 40.7°C, respiratory rate was 35/min, SpO2 was 83% (oxygen intake flow was 10 L/min), leukocyte was 11.2×109/L, lymphocyte count was 0.5×109/L, and PCT was 0.202 ng/mL. The dosage of methylprednisolone was increased to 40 mg with 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution intravenously, once every 12 h. Human immunoglobulin was added intravenously (20 g once daily); Zadaxin (thymosin alpha-1) was added by subcutaneous injection (1.6 mg, once daily). His temperature was normal, and shortness of breath improved slightly.

On January 31, SpO2 was 88% (oxygen intake flow was 10 L/min). Reexamination of the chest CT showed large exudative shadows in both lungs (Figure 1C).

On February 1, SpO2 was 92% (oxygen intake flow was 10 L/min), and the respiratory rate was 28/min. On February 2, SpO2 was 95% (oxygen intake flow was 5 L/min), and the respiratory rate was 25/min. The dosage of methylprednisolone was reduced to 40mg with 10mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution (intravenous, once daily). On February 3, SpO2 was 94% (oxygen intake flow was of 3 L/min), the lymphocyte count was 0.3×109/L, and hsCRP was normal. Another chest CT showed that pulmonary inflammation had reduced (Figure 1D).

On February 4, the patient’s SpO2 was 98% (oxygen intake flow was 3 L/min). Intravenous injection of methylprednisolone was reduced to 20 mg with 10 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride solution, once daily. Another throat swab came up negative for the 2019-nCoV nucleic acid test. On February 5, SpO2 was 94% (air intake), and breathing difficulties had improved significantly; human immunoglobulin was reduced to 10g (intravenous drip, once daily). On February 6, SpO2 was 98% (air inhalation), the heart rate was 115/min, and medication was stopped. The nucleic acid test was negative on February 9, and the patient was discharged on February 10.

The patient was successfully treated and discharged after 19 d in the hospital. At the 3-mo follow-up, the patient had recovered well.

According to the patient’s symptoms, signs, epidemiological history, and contact history, a positive 2019-nCoV virus nucleic acid test by a throat swab and chest CT, it was confirmed that the patient met the diagnosis of COVID-19. The results of Nan-Shan Zhong’s team study showed that 43.8% of the patients had fever symptoms in the early stage, and 87.9% of them had fever after admission[5]. The laboratory examination of COVID-19 showed that the total number of leukocytes in the peripheral blood was normal or decreased in the early stage of the disease; the lymphocyte count decreased; some patients had an increase in liver enzyme, lactate dehydrogenase, muscle enzyme and myoglobin; and some critical patients could see an increase of troponin. CRP and ESR increased in most patients, and PCT was normal. In severe cases, D-dimer increased, and peripheral blood lymphocyte decreased progressively. The 2019-nCoV nucleic acid can be detected in nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, lower respiratory tract secretions, blood, feces, and other specimens[6]. In the early stage of the disease, the total number of white blood cells in this patient was normal, lymphocyte count decreased, hsCRP increased, and PCT was normal. The pharyngeal swab was positive for 2019-nCoV virus nucleic acid. All of these met the typical characteristics of COVID-19 laboratory examination. In the early stage, the patient’s chest CT had single or double lung multiple ground-glass shadows. The lesions were mainly distributed around the lung and under the pleura. The image of the uninjured lung was normal. During the recovery period, the pulmonary lesions were absorbed, and fibrous foci formed. All of these were consistent with the imaging findings of COVID-19[7]. In the course of diagnosis and treatment, the patient gradually progressed to the severe stage[4], mainly shown by a progressive decrease of lymphocytes, a sudden rise of body temperature (40.7°C), shortness of breath (35/min), a decrease of oxygen saturation (SpO2 of 83% with oxygen inhalation at 10 L/min flow), the rapid progress of chest CT manifestations, increased the number of lesions, significantly expanded the range, increased the density, and the distribution of lesions from peripheral to central.

Although no effective antiviral drugs and treatment methods have been confirmed, antiviral drugs should be used as early as possible and in the whole process. The patient was given oseltamivir orally on the day of admission, lopinavir and ritonavir tablets were given orally on the 3rd d of admission. Lopinavir and ritonavir tablets are a compound preparation of lopinavir and ritonavir. Lopinavir is an improved viral replicase inhibitor based on ritonavir. Ritonavir increases the half-life of lopinavir by inhibiting cytochrome, thus enhancing the pharmacokinetics of lopinavir[8]. Of the 99 novel coronavirus patients isolated from the Wuhan Jinyingtan Hospital, 75 received treatment with lopinavir and ritonavir tablets and other antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir and ganciclovir[9]. Although the efficacy of lopinavir and ritonavir tablets for the treatment manual of novel coronavirus is still lacking in pre-clinical data[10], currently the National Health Commission and the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine recommend lopinavir and ritonavir tabletsfor the treatment manual of the novel coronavirus[11].

Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce cytokine storm[12]. During the outbreak of SARS in 2003, corticosteroids were widely used for the clinical treatment of SARS patients[13]. However, recent studies on SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome patients have shown that corticosteroid therapy will not reduce the death rate but will delay the elimination of the virus[14,15]. Corticosteroids also inhibit immune function and increase the risk of infection. Therefore, in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection patients, corticosteroids should be used with caution. Our experience is that corticosteroids should not be used for fever reduction in the early stage. In the middle and late stages, they should be used for a short time depending on whether there is immune overactivity, whether there is oxygen saturation in patients (whether there is hypoxemia), whether there is progress in chest CT (whether it develops to the advanced stage or the severe stage) and whether there is a continuous decrease of lymphocytes[6]. In this paper, the patient’s peripheral blood lymphocyte decreased progressively, and on January 30, the body temperature rose sharply (40.7°C), respiration was rapid (35/min), and oxygen saturation decreased (SpO2 of 83% with oxygen inhalation at 10 L/min flow), which indicated that the patient’s condition was progressing to the critical stage, so on January 30, the dosage of methylprednisolone was increased to 40mg, once every 12 h, and the dosage was reduced on February 1 (3 d) after the symptoms were controlled.

For severe or critical COVID-19 patients, combined immune boosters are recommended based on general treatment. Intravenous injection of gamma globulin can rapidly increase the concentration of blood immunoglobulin G by three to six times, thus affecting the body’s passive immune function. Particularly when the corticosteroid dose is large, it should be used actively[16]. In this case, when the patient progressed to the critical stage on January 30, the dosage of human immunoglobulin (20g, intravenous drip, once per day) was increased on the same day, and the treatment was combined with subcutaneous injection of Zadaxin (thymosin alpha-1), which had the desired effect.

At present, there is no “gold standard” to judge the condition of COVID-19. Therefore, we should “observe the multiple indicators dynamically” in the evaluation of the disease. (1) Body temperature. The results showed that nearly half of the patients with COVID-19 had no fever in the early stage, and 87.9% had fever only after admission, so it is not enough to evaluate the progress of the disease only by temperature. However, for patients with fever symptoms, body temperature monitoring can help to judge changes of conditions, and it is one of the necessary indexes to release the patient from quarantine. (2) The number of lymphocytes. Novel coronavirus pneumonia patients during early laboratory examination had a decrease in peripheral blood lymphocyte count. Severe patients showed a progressive reduction. Lymphocytes reflect the immune function of the patients, so it can be used as an indicator to monitor disease development. (3) BloodSpO2. Blood SpO2 is one of the reliable indexes that directly reflect pulmonary function. It is easy to operate in clinic and can be used to help judge the condition. And (4) Lung CT. The CT image of early lesions has certain characteristics, which can be used to evaluate the nature and scope of the lesions and is the preferred imaging examination method of COVID-19[17]. The imaging manifestations of COVID-19 changed rapidly, so the chest examination can be performed once every 3 to 5 d if CT conditions permit. However, the imaging features of pneumonia are not specific, similar to many other viral infections, and not suitable for the examination of severe patients, which should be paid attention to in clinical practice.

COVID-19 has certain clinical characteristics and typical imaging features. COVID-19 in young adults can be cured by active treatment.

Thanks to Dr. Bo-Ning Han for his careful polishing of the manuscript. We thank all the people who are fighting against the epidemic.

| 1. | The 2019-nCoV Outbreak Joint Field Epidemiology Investigation Team; Li Q. Notes from the field: an outbreak of NCIP (2019-nCoV) infection in China-Wuhan, Hubei Province, 2019–2020. Chin CDC Weekly. 2020;2:79-80 Available from: http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e3c63ca9-dedb-4fb6-9c1c-d057adb77b57. |

| 2. | Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5202] [Cited by in RCA: 4710] [Article Influence: 785.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 3. | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11409] [Cited by in RCA: 11616] [Article Influence: 1936.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | The General Office of National Health Commission. COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment Protocol (trial version 5th,revised version). Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/d4b895337e19445f8d728fcaf1e3e13a/files/ab6bec7f93e64e7f998d802991203cd6.pdf. |

| 5. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 19026] [Article Influence: 3171.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 6. | National Health Commission. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus-infected Pneumonia (Trial version 6). Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2/files/b218cfeb1bc54639af227f922bf6b817.pdf. |

| 7. | Chinese Radiology Society. Radiological diagnosis of COVID-19: recommendations of Chinese radiology society (1st edition). ZhonghuaFangshexueZazhi. 2020;54. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Chu CM, Cheng VC, Hung IF, Wong MM, Chan KH, Chan KS, Kao RY, Poon LL, Wong CL, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Yuen KY; HKU/UCH SARS Study Group. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1117] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14869] [Cited by in RCA: 13064] [Article Influence: 2177.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 10. | Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4848] [Cited by in RCA: 4440] [Article Influence: 740.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | National Health Commission. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus-infected Pneumonia (Trial version 4). Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202001/4294563ed35b43209b31739bd0785e67/files/7a9309111267475a99d4306962c8bf78.pdf. |

| 12. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30483] [Article Influence: 5080.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 13. | Stockman LJ, Bellamy R, Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 861] [Cited by in RCA: 862] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lansbury LE, Rodrigo C, Leonardi-Bee J, Nguyen-Van-Tam J, Shen Lim W. Corticosteroids as Adjunctive Therapy in the Treatment of Influenza: An Updated Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e98-e106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, Jose J, Pinto R, Al-Omari A, Kharaba A, Almotairi A, Al Khatib K, Alraddadi B, Shalhoub S, Abdulmomen A, Qushmaq I, Mady A, Solaiman O, Al-Aithan AM, Al-Raddadi R, Ragab A, Balkhy HH, Al Harthy A, Deeb AM, Al Mutairi H, Al-Dawood A, Merson L, Hayden FG, Fowler RA; Saudi Critical Care Trial Group. Corticosteroid Therapy for Critically Ill Patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2018;197:757-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 720] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 113.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yang LR, Zhang YF, Xu Y, Chen GB, Li B, Zhong L. Observation on the short-term efficacy of high-dose gamma globulin shock therapy in the treatment of acute severe viral pneumonia. Shandong Yiyao. 2011;51:90-91. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, Zhang L, Jiang S, Huang D, Chen B, Zhang Z, Guan W, Ling Z, Jiang R, Hu T, Ding Y, Lin L, Gan Q, Luo L, Tang X, Liu J. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:1275-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 492] [Article Influence: 82.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Phan TS-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Xing YX