Published online Jun 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2294

Peer-review started: January 4, 2020

First decision: April 8, 2020

Revised: April 24, 2020

Accepted: May 23, 2020

Article in press: May 23, 2020

Published online: June 6, 2020

Processing time: 155 Days and 4.6 Hours

Pain of the zygomatic arch region is common among patients with orofacial pain, especially in those with temporomandibular disorder-related pain of a myogenic origin. Since zygomatic arch pain may occur due to various causes other than muscle pain, appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning is essential to ensure its successful management. Unfortunately, zygomatic arch pain has not been handled as an independent clinical feature until now, and studies have mainly focused on pain resulting from trauma and surgical procedures.

We describe 7 independent cases, all of which presented with the identical chief complaint of pain in the zygomatic arch region. However, the underlying causes were different for each, being myofascial pain, myositis, tooth crack, dental caries, sinusitis, neuropathic pain, and salivary gland tumor respectively. In this case report, the clinical features of each case are investigated and diseases to be considered in the diagnostic process are suggested, along with the diagnostic modalities (including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) that can lead to the appropriate final diagnosis.

Zygomatic arch pain is a common complaint encountered in the orofacial pain clinic but may lead to misdiagnosis. Clinicians must have in-depth knowledge of the possible differential diagnoses and evaluation tools.

Core tip: Many patients visiting the orofacial pain clinic have zygomatic arch pain as their chief complaint. However, the pain that the patient describes may not always originate from the masseter muscle, as easily considered. The orofacial region is a common site for referred pain and is frequently the cause of misdiagnosis and confusion for both the clinician and patient. This report examines the various diagnostic results of 7 patients with chief complaint of pain in the zygomatic arch region, including myofascial pain, myositis, odontogenic pain, sinusitis, neuropathy, and salivary gland tumor. Imaging and diagnostic anesthesia should be understood to avoid misdiagnosis.

- Citation: Park S, Park JW. Various diagnostic possibilities for zygomatic arch pain: Seven case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(11): 2294-2304

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i11/2294.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i11.2294

Many patients visit a pain clinic with the complaint of orofacial pain associated with the zygomatic arch region. However, the pain that the patient describes may not always originate from the masseter muscle that is attached to the medial side and lower border of the zygomatic arch bone. The zygomatic arch is surrounded by various structures, including masticatory muscles (masseter, temporalis, lateral pterygoid, and medial pterygoid muscle), trapezius muscle, splenius capitis muscle, anterior digastric muscle, posterior digastric muscle, coronoid process, temporomandibular joint (TMJ), maxillary teeth, and the maxillary sinus, all of which can produce pain in the zygomatic arch area. Referred pain from remote areas may also present in the same region. In this case, the source of pain must be identified and targeted to determine appropriate treatment and obtain successful results.

Referred pain is the recognition of pain sensation in areas other than that of the original noxious stimulation. Referred pain can occur from both visceral and somatic structures[1]. Somatic referred pain is recognized at the site that shares the same segmental innervation as the source of the pain[2]. Whatever the cause of the symptoms, secondary hyperalgesia frequently occurs in the referral area[3]. Studies have shown that if the source pain lasts for more than a certain amount of time, the pain in the referral area does not disappear even when the original cause of pain is removed[4]. This suggests that pain in the referral area can afflict the patient chronically, persisting beyond removal of the original pain source through treatment. The orofacial region is a common site for referred pain and is frequently the cause of misdiagnosis and confusion for both the clinician and patient[5,6]. Therefore, understanding referred pain, locating the pain source, and treating both the original pain source and referred pain-related symptoms are essential for the orofacial pain specialist to successfully reduce the patient's overall pain level.

This review examines the various diagnostic results of patients who visited our orofacial pain clinic with a chief complaint associated to pain in the zygomatic arch region. Since accurate differential diagnosis is essential for the successful prognosis of treatment, the clinical characteristics and diagnostic processes of 5 case categories (7 patients, Table 1) are presented herein. In addition, other possible diagnoses of orofacial pain are analyzed through previous literature with the purpose of providing the readers with a comprehensive review of orofacial pain associated with the zygomatic arch region.

| Diagnosis | Quality | Duration | Severity | Accompanied symptoms | Diagnostic methods |

| Myofascial pain | Dull | Continuous | Moderate | Headache | Muscle palpation for tender muscle/taut band |

| Myositis | Pricking; Throbbing | Continuous; Intermittent | Moderate to severe | - | MRI, CT |

| Odontogenic pain | Various according to tooth condition | Various according to tooth condition | Mild to severe | - | Intraoral examination for caries and cracks; Plain radiography; Diagnostic anesthesia |

| Sinusitis | Dull | Continuous | Mild to moderate | Postnasal drip, nasal congestion, purulent anterior rhinorrhea, foul smell or taste; Headache | CT |

| Neuropathic pain | Sharp; Shooting; Electric shock-like | Intermittent | Moderate to severe | - | Brain imaging when necessary |

| Salivary gland tumor | Stabbing | Continuous | Severe | Trismus | MRI, CT, PET |

Chief complaints: A 25-year-old female visited our orofacial pain clinic with the chief complaint of continuous pain in the zygomatic arch area and both masseter muscles. She described the pain as having a throbbing quality and with a score of 5 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale (NRS).

History of present illness: The patient stated that the pain had initially occurred 4 mo before the first visit. The patient reported parafunctional habits, including nocturnal clenching and bruxism. She also reported the pain level increasing with psychologically stressful events.

History of past illness: The patient had an insignificant medical history.

Physical examination: Clinical examinations were conducted according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) diagnostic protocol[7]. The maximum mouth opening was 35 mm and was accompanied by pain in both masseter muscles. The patient did not complain of any pain in the TMJ area during function and not on palpation of this area. Right joint noise and tenderness on palpation of both masseter areas were observed. Tongue and buccal mucosa ridging were evident.

Imaging examinations: Plain radiographs, including orthopantomogram, TMJ panoramic, and transcranial view, were evaluated. Bone scintigraphy was also conducted since the joint noises were diagnosed as crepitus, in order to differentiate between arthrosis and arthritis. A mildly active lesion was identified in the left TMJ. However, the patient’s spontaneous and provoked pain was focused in the masseter area and the surface irregularity of the condyle observed through plain radiography was not evident.

Chief complaints: A 54-year-old male visited the orofacial pain clinic with complaints of limitation and pain at mouth opening and severe pain in the left TMJ and left zygomatic arch region at rest that worsened with mandibular movement. The pain was of a pricking and squeezing quality, with a level of 9 on a 0-10 NRS.

History of present illness: The patient reported that the pain had initially occurred 1 mo before the first visit.

History of past illness: The patient’s medical history included surgery and radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma 20 years ago.

Physical examination: Clinical examinations conducted following RDC/TMD revealed a slightly decreased maximum mouth opening range (36 mm), without pain and tenderness on palpation of the left masseter area.

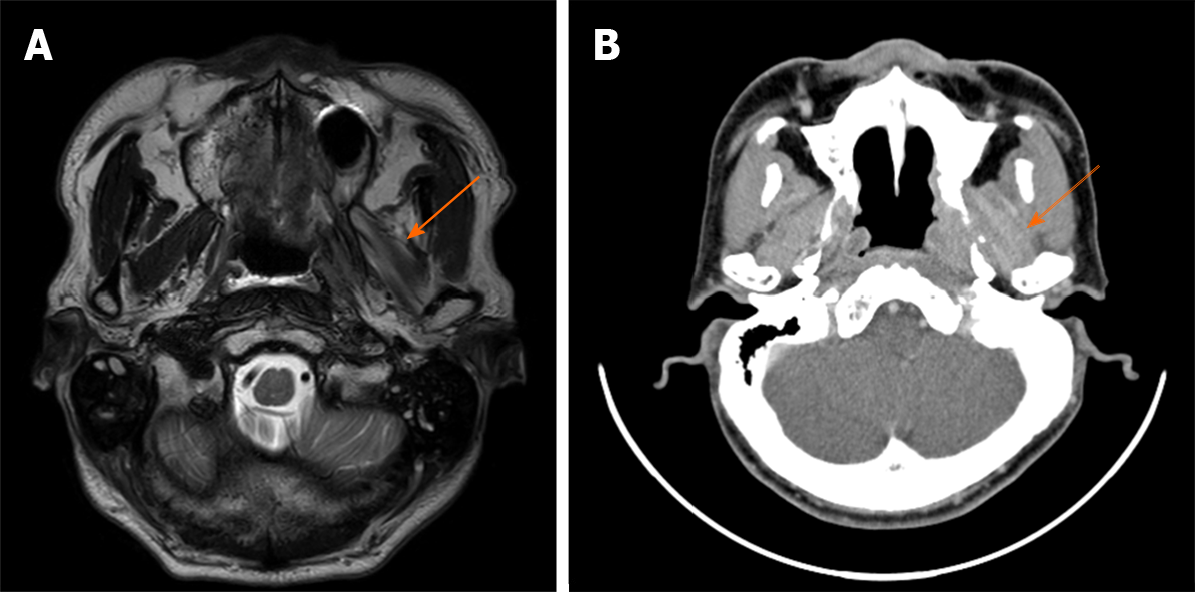

Imaging examinations: Plain radiographs (orthopantomogram, TMJ panoramic, and transcranial view) showed no specific findings. The initial diagnosis was masticatory muscle pain. Conservative treatment including physical therapy, exercise, habit control and medication [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and clonazepam] were applied; however, there was no change in pain level after 3 wk of treatment. Carbamazepine was then prescribed based on a second diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia (TN). Following 3 wk of medication, the pain level had slightly decreased to NRS 6 but the maximum mouth opening range had decreased to 30 mm. Enhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were conducted. Although the disc-condyle relationship was normal in both sides of the MRI sagittal view, effusion was observed in the left mastoid region. In the T2 MRI axial view, heterogeneous high signals were observed in the left lateral pterygoid and temporal muscle region. Also, fluid signals filling the left mastoid air cells, part of the middle ear and external auditory meatus were observed. Enhanced CT findings showed irregular bony destruction of the sphenoid bone, and enhanced signal intensity was observed in the left lateral pterygoid muscle, mastoid air cells and the external auditory canal, indicating the presence of inflammation (Figure 1).

Chief complaints: A 31-year-old male visited the orofacial pain clinic with complaint of pain in the right zygomatic arch region.

History of present illness: The patient stated the pain had initially occurred 3 d before the first visit and was sharp, intermittent pain appearing about 5-6 times a day, with each episode lasting 10 min. The pain level was 8 on a 0-10 NRS. The patient stated that he had heard that there was no abnormality in the orthopantomogram taken at the dental clinic where he had visited. There were no evident aggravating or alleviating factors.

History of past illness: The patient had an insignificant medical history.

Physical examination: Clinical examinations following RDC/TMD revealed no clinical features related to TMD other than clicking noise in the right TMJ.

Imaging examinations: The mandible and maxilla CT showed no abnormalities.

Further diagnostic work-up: Carbamazepine (100 mg/d before sleeping) and gabapentin (300 mg/d gradually increased to 900 mg/d over a 3-d period) were prescribed for 2 wk following an initial diagnosis of TN. Since hepatotoxicity and blood dyscrasia are well known possible side-effects of carbamazepine, baseline hematologic tests [including complete blood cell count with white blood cell differential and blood chemistry, with liver function tests such as for alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, albumin and total protein] were conducted and planned every 3 mo and following increase in dosage[8]. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping was not done based on the fact that the frequency of HLA-B*15:02 (< 2.5%) and HLA-A*31:01 (5%) genotypes, which are known to be related to cutaneous adverse reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, are relatively low in South Koreans[9].

Case 2.2: Odontogenic pain –dental caries

Chief complaints: A 24-year-old female presented with complaint of right zygomatic arch pain following orthodontic treatment.

History of present illness: The patient stated that the pain had occurred 1 mo before the first visit and the pain level was 5 on a 0-10 NRS. Mandibular movements tended to aggravate the pain.

History of past illness: The patient had an insignificant medical history.

Physical examination: Clinical examinations following RDC/TMD revealed a normal maximum mouth opening width (44 mm) accompanied by right masseter muscle pain. Right TMJ noise and tenderness on palpation of the right masseter area was also observed. An old resin restoration was observed to be partially removed from the right upper first molar and the tooth was sensitive to percussion.

Imaging examinations: Plain radiography (orthopantomogram, TMJ panoramic, transcranial view and periapical radiographs of the right upper first molar) and cone beam CT (CBCT) were conducted. Incipient degenerative bone change was observed in both TMJ condyles.

Further diagnostic work-up: The initial diagnosis was masticatory muscle pain. Conservative treatment including physical therapy, exercise, habit control, and stabilization splint were applied with monthly recall checks. At 5 mo after treatment initiation, the pain of the masseter muscle region was totally resolved; however, pain of the zygomatic arch region persisted. An intraoral examination was performed once again, and infiltration anesthesia on the right upper first molar was followed by immediate subsidence of the pain.

Chief complaints: A 47-year-old female visited the orofacial pain clinic with complaint of throbbing pain in the left zygomatic arch to nose region. The pain level was 4 on a 0-10 NRS. The pain was more evident at rest, rather than while chewing or speaking.

History of present illness: The patient reported the pain having started 3 years prior, which was followed by numerous hospital visits of various specialties but without a definite diagnosis or significant improvement.

History of past illness: The patient’s medical history included headaches accompanied by severe pain followed by brain MRI with normal results. A neurologist diagnosed the case as TN, with ensuing carbamazepine prescriptions that were ineffective.

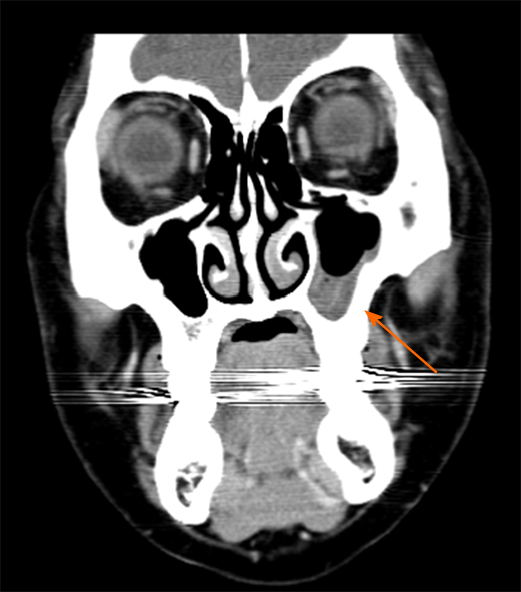

Imaging examinations: CBCT was conducted to rule out the possibility of an inflammatory lesion. Mucosal thickening of the floor of the left maxillary sinus was observed on the CT images (Figure 2).

Chief complaints: A 54-year-old female visited the orofacial pain clinic with complaints of severe pain in both the right maxillary gingiva and right zygomatic arch region. The pain had a sharp and electrical quality, lasting less than 5 min for each episode and divided by pain-free intervals. The pain was unilateral and located in the territory of the maxillary nerve and could be provoked by touching this area. The pain level was 10 on a 0-10 NRS. The pain appeared intermittently, approximately 10 times a day.

History of present illness: The pain had occurred 2 wk before the first visit, without remission. The patient did not report any specific incidents related to the initiation of pain. No other concomitant symptoms, including autonomic presentations, were reported. The patient stated that analgesics such as NSAIDs had no effect.

History of past illness: The patient had an insignificant medical history.

Physical examination: There were no specific findings from the intraoral examination.

Chief complaints: A 69-year-old male visited the orofacial pain clinic complaining of mouth opening restriction and pain in the left zygomatic arch region. The pain was of a stabbing and radiating quality. The pain level was 8 on a 0-10 NRS.

History of past illness: The patient’s medical history included surgical and radiation therapy for salivary duct carcinoma of the left parotid gland that occurred 6 mo prior. The patient reported that the pain began after receiving radiation therapy.

Physical examination: Clinical examinations conducted following RDC/TMD revealed a restricted maximum mouth opening range (23 mm) accompanied by left masseter muscle area pain and tenderness on palpation of the left masseter area.

Imaging examinations: Plain radiographs (orthopantomogram, TMJ panoramic, and transcranial view) showed limitation of TMJ condyle movement.

The initial diagnosis was masticatory muscle contracture due to radiation therapy. Conservative treatment including physical therapy, exercise, habit control and medication (NSAIDs, tramadol, and clonazepam) were applied; however, the pain level increased to NRS 9-10 and the maximum mouth opening range was reduced to 18 mm after 3 wk of treatment. The patient was referred to an otorhinolaryngologist, upon which he underwent positron emission tomography and MRI.

The main cause of the patient’s zygomatic arch pain was diagnosed as myofascial pain of both masseter muscles. Osteoarthrosis of the left mandibular condyle was also present.

The final diagnosis was osteoradionecrosis (ORN) due to radiation therapy, and myositis of the left lateral pterygoid muscle which was the cause of pain in the left zygomatic arch region.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was toothache due to tooth crack.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was toothache due to dental caries.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was left maxillary sinusitis.

The case was clinically diagnosed as TN.

The diagnosis for this case was recurrence of a salivary duct carcinoma.

Conservative treatment with physical therapy, exercise, habit control and stabilization splint were applied. Medication included NSAIDs for pain control. Clonazepam (0.5 mg/d taken 30 min before going to bed) was added for 2 wk based on history of several failed attempts in reducing pain with analgesics only and also to address the concomitant sleep problems reported by the patient, in spite of the drug’s potential to cause abuse[10].

The patient belatedly reported episodes of pus and blood discharge from his ears. The patient was referred to an otorhinolaryngologist and the pain was relieved following appropriate medication including NSAIDs and antibiotics.

The patient reported that the initial pain medication was ineffective. A crack of the right upper first molar was identified during further intraoral examination and the zygomatic arch pain was completely relieved following endodontic treatment of the problematic tooth.

The patient received treatment of the secondary caries under the resin restoration, and the zygomatic arch pain was totally resolved.

The patient was referred to an otorhinolaryngologist and the patient reported that the zygomatic arch pain decreased to NRS 2 after endoscopic sinus surgery and medication for the left maxillary sinusitis. The patient did not return for further evaluations thereafter.

Carbamazepine (100 mg/d before sleeping) and then combination therapy of carbamazepine (100 mg/d before sleeping) and gabapentin (300 mg/d after lunch) relieved the zygomatic arch pain by 80% after 3 d of medication. Gabapentin was added to provide additional pain relief without increasing the dosage of carbamazepine, to avoid side effects such as dizziness and nausea. Carbamazepine is currently the most commonly applied drug for TN and is known to be highly effective in controlling TN pain, showing a reduction in attacks in up to 88% of patients in less than 4 wk, and the effect is immediate in many cases. Gabapentin is also known to be as efficacious but with less adverse reactions[11].

Baseline hematologic tests, including complete blood cell count with white blood cell differential, and blood chemistry with liver function tests were conducted and planned every 3 mo, and following any increase in carbamazepine dosage. HLA genotyping was not done based on reasons described in the case of odontogenic pain[9].

Surgical excision of the recurrent salivary duct carcinoma was performed. After surgery, the zygomatic arch pain subsided over the recovery period.

The pain was fully controlled following 6 mo of monthly recall checks and treatment (described above). However, after usage of the stabilization splint was terminated, pain in the zygomatic arch area returned. Therefore, stabilization splint therapy, physical therapy, and medication were applied again and the pain remained controlled, and the maximum mouth opening range increased to 40 mm at 20 mo post-treatment.

Often, patients complaining of pain of the zygomatic arch region seek the orofacial pain clinic, and specialists too quickly determine the cause of pain as the masticatory muscles based on empirical evidence[12]. This may be true in many cases, but this case series shows that various conditions may present as orofacial pain associated with the zygomatic arch and accurate diagnosis may be further hindered due to coincidence of masticatory muscle pain along with other ailments. As shown in this case series, myositis, odontogenic pain, neuralgia, sinusitis, and salivary gland tumor are other possible causes of orofacial pain that could be encountered in the clinic. Correct differential diagnosis is critical since treatment planning and ultimately the patient’s prognosis depend on it.

Myofascial pain is characterized by localized muscular pain with a tight, sensitive focal area called the trigger point[13]. Clinical features of myofascial pain include pain at rest, increased pain with function, and limitation of muscle movement. Patients generally describe the pain as deep and aching[14]. The trigger point can induce central excitatory effects, and referred pain often appears in a predictable pattern depending on the location of the trigger point[15]. Referred pain appears in the zygomatic arch region when trigger points located in the temporalis, masseter, lateral and medial pterygoid muscles are pressed. Therefore, if the pain source is originally in the above-mentioned muscles, pain in the zygomatic arch area may be present. Notably, referred pain in the zygomatic arch region has been reported as most frequently caused when trigger points of the lateral pterygoid muscle are compressed[16]. Therefore, when the patient complains of pain in the zygomatic arch region, the masticatory muscles should be evaluated carefully to identify the true source of pain.

The lateral pterygoid muscle may be easily omitted in the evaluation process to find the cause of zygomatic arch pain since clinicians tend to palpate only the muscles that can be approached extra-orally. However, it is necessary to perform intra-oral palpation and functional manipulation to investigate all candidate muscles that could be causing the zygomatic arch pain. Functional manipulation of the lateral pterygoid muscle can be done by allowing the patient to protrude the jaw against resistance provided by the clinician. Similarly, when myositis inflicts the above-mentioned muscles, zygomatic arch pain may be present. Infection, trauma or persistently elevated muscle tension may cause inflammation. Myositis can be divided into infectious and non-infectious subtypes. In non-infectious myositis, prolonged muscle pain may lead to a change in the central nervous system, thus resulting in centrally mediated myalgia which is associated with neurogenic inflammation. However, infectious myositis occurs with bacterial or viral infections and is accompanied by typical signs of inflammation, such as swelling, rupture, and fever[13].

In our case of myositis, ORN caused by radiotherapy resulted in inflammation of the surrounding muscles, including the lateral pterygoid and temporalis muscle. The fact that the patient received radiotherapy very long ago hindered the diagnostic process, but reports that ORN had occurred 3-15 years after radiation treatment should be considered[17]. In the above case, both the initial diagnosis of masticatory muscle pain and second diagnosis of neuropathic pain based on only clinical examination and plain radiographs were wrong and only after advanced imaging, including MRI and CT, were done was a correct diagnosis of ORN and myositis made. Therefore, detailed history taking is important in the diagnosis of patients who complain of zygomatic arch pain, and appropriate imaging including CT and/or MRI should be performed, especially when the clinical symptoms are not typical of a given diagnosis and the patient does not respond well to conventional treatment approaches. The diagnosis of ORN is generally based on the identification of symptoms such as odor, headache, purulent debris, and intermittent bleeding. CT and endoscopy are recommended as additional diagnostic tools[17]. The clinical symptoms of the patient may have been caused by ear infections that led to the enhancement in the mastoid process region in the MRI; however, the otorhinolaryngologist did not find any evident symptoms through ear inspections, so the mastoid process lesion was considered secondary to the lateral pterygoid muscle inflammation. Treatment of myofascial pain is generally conservative including medication, physical, and behavioral therapy[13]. On the other hand, when the pain is due to myositis caused by radiation therapy as presented in this report treatment with antibiotics may be called upon and a multidisciplinary approach may be necessary depending on the source of infection.

Odontogenic pain of the upper teeth may cause zygomatic arch pain. For accurate differential diagnosis, attention should be paid to the characteristics of the patient's pain. Patients with muscle pain generally feel a dull ache following the muscle distribution. Odontogenic pain worsens with heat and cold stimuli, and reacts to percussion[18]. A cracked tooth, identified through intraoral examination, can be further evaluated by vitality testing[19] with positive responses and percussion in an axial direction with negative responses[20]. The 2 cases we introduced were each caused by tooth crack and secondary caries. These cases are often difficult to diagnose since symptoms are unclear radiographically and clinically in their early stages. Diagnostic anesthesia is a very useful method that may be applied in such situations[21]. In the case of odontogenic pain, pain is dramatically relieved following anesthesia of the causative tooth. The second case of odontogenic pain was especially difficult to diagnose because of concomitant muscle problems. Even in such a situation, diagnostic anesthesia could be successfully applied to find and solve the cause of pain in the zygomatic arch region.

The maxillary sinus is part of a series of paranasal sinuses, that includes the frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses. Maxillary sinusitis causes a constant burning pain, with zygomatic and dental area tenderness[22]. Maxillary sinusitis causes continuous pain of a dull, aching, and tender quality, with mild to moderate severity, and could be unilateral or bilateral[23]. Other symptoms include postnasal drip, nasal congestion, purulent anterior rhinorrhea, foul smell or taste, and fatigue[24]. Radiographic examinations such as CT or MRI can play a key role in the diagnosis of maxillary sinusitis[23]. In chronic maxillary sinusitis, it is recommended that imaging be performed requisitely because symptoms may not be characteristic. The reported patient had already visited various hospitals for 2 years before the first visit to our hospital, with the aim of obtaining a definite diagnosis. In our case, symptoms such as headache and pain on pressure of the zygomatic arch and masseter region caused confusion. However, the diagnosis of sinusitis was confirmed by CT and the patient did not complain of persistent pain once the sinusitis was treated, making it possible to rule out neuropathic pain of the superior alveolar nerves secondary to long-term sinus inflammation.

Neuropathic pain should be considered as a possible cause of zygomatic arch pain since the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve is distributed in the zygomatic arch region. A good illustration would be infraorbital neuralgia, which is caused by a branch of the maxillary nerve and is known to be accompanied by zygomatic arch pain[25]. Previous report showed that such pain could be temporarily relieved by infraorbital nerve block and controlled by pregabalin intake after failing with several drugs, including carbamazepine and amitriptyline[25]. The diagnosis of neuralgia is primarily based on patient history. Patients with neuralgia mainly complain of sharp, shooting, stabbing and electric shock-like pain which appears unilaterally in most cases. In the case of TN, pain is triggered by non-painful stimulation, such as soft touching of the affected area or even speaking[18]. However, in some patients, the paroxysms are less intense, and may appear as a deep dull or burning sensation. Response to drugs can also be a key to diagnosis. Neuralgia responds to drugs such as carbamazepine or tricyclic antidepressants without showing significant response to NSAIDs. In addition, MRI should be performed to rule out secondary neuralgia with an organic lesion affecting the nerve[27].

Salivary gland tumor is another possible cause of zygomatic arch pain. In our case, the patient had already undergone surgery and radiation therapy for salivary gland tumors; therefore, the initial diagnosis was incorrectly made as myofascial pain with limited mouth opening due to surgery and radiation therapy. However, there was no response to physical therapy and medication, and the pain was relatively strong compared to the general pain intensity of muscle pain[28]. Maximum mouth opening was also severely limited to 18 mm. Such clinical characteristics called for a consultation to the department of otorhinolaryngology to reassess the surgical site, and recurrent salivary gland tumor was confirmed through positron emission tomography and MRI. Malignant salivary gland tumors are very rare and the most common tumor site is the parotid gland[29]. Clinical features include pain, facial nerve involvement, and parapharyngeal and palatal fullness. In addition, trismus and skin ulceration may appear in severely advanced malignancies[30,31]. Therefore, when patients with zygomatic arch pain show restricted mouth opening simultaneously with the above-mentioned symptoms, CT and MRI should be performed and appropriate consultations should be made.

Other possible diagnoses related to zygomatic arch pain have been reported in previous literature. In TMD patients with temporal tendinitis, 49% complained of referred pain in the zygomatic arch region[32]. A case report presented a patient with temporal tendinitis showing continuous squeezing pain in the zygomatic arch and temporalis regions, with increased pain during mandibular movements[33]. The diagnosis of temporal tendinitis is based on clinical features of tenderness and/or pain at the tendon insertion site and temporalis muscle, restricted mandibular movement, and the reduction of pain with local anesthesia of the originally afflicted site. Elongation of the coronoid process may appear on radiographic examination but its relation to the diagnosis is still controversial[34]. Temporal tendinosis has also been cited as a cause of orofacial pain in recent literature so should be considered when the patient complains of pain occurring in the zygomatic arch region[35]. Tendinitis is inflammation located in the tendon, while tendinosis is a degenerative state caused by persistent overuse and lacks signs of inflammation both clinically and histologically[36]. Tendinosis is commonly misdiagnosed as tendinitis. Temporal tendinosis is typically accompanied by chronic pain of the orofacial region and stiffness in the temporalis muscle area that is exacerbated by jaw function. Mouth opening limitation can be observed in certain cases. Temporal tendinosis can be easily overlooked in the differential diagnosis of pain in the zygomatic arch region because of the anatomic complexity of the area. Since palpation shows low sensitivity and specificity in its diagnosis imaging, especially ultrasound should be considered when the presence of temporal tendinosis is questioned[35].

Referred pain due to coronary insufficiency may also appear in the mandible, zygomatic arch, and temporal region[37]. A case was reported where facial pain, including the zygomatic arch, was caused by myocardial infarction[38]. A previous review summarized that referred pain due to cardiac origins may appear in the maxilla, mandible, zygomatic arches, submandibular, neck, temporalis muscle and teeth regions[39]. The underlying mechanism of such pain referral is complicated and it would be difficult to locate a single transmission route, but cardiac etiology could be another possibility when the cause of orofacial pain is not clinically evident[40].

Posterior scleritis can also cause zygomatic arch pain[36]. Posterior scleritis is rarely known to cause facial pain. The main area of pain is periocular but may also appear as referred pain in the forehead, zygomatic arch, and temple region. The pain is generally described as increasing with ocular movement. Visual disturbances and other ocular signs are also accompanying. Visual loss is a critical complication of posterior scleritis that may occur[41], so posterior scleritis should be suspected and measures for accurate diagnosis should be taken when a patient with zygomatic arch pain complains of concomitant ocular symptoms, to avoid irreversible outcomes.

Although relatively rare, various neoplasms of the maxillofacial region could also be another possibility. In osteochondroma affecting the coronoid process, pain was not a common symptom, but approximately 10% of the cases reported facial pain[42]. With peripheral osteoma of the zygomatic arch, some patients complained of pain[43]. When the complaint of pain in the zygomatic arch region is accompanied by swelling, facial asymmetry, and limited mouth opening, appropriate imaging should be performed with the above diagnoses in mind.

This is the first case series report to describe various cases of orofacial pain with the zygomatic arch region as the main pain focus. Although this report has inherent limitations as a case series and retrospective analysis, it provides the clinician with a comprehensive summary of possible differential diagnoses by concentrating on the patients’ identical chief complaint – pain in the zygomatic arch region – then inversely providing the full diagnostic processes for its various underlying diseases.

Zygomatic arch pain is commonly reported by patients visiting the orofacial pain clinic and is majorly accepted to be caused by masseter muscle pain. But a variety of conditions may present as orofacial pain in the zygomatic arch region, including life-threatening diseases such as salivary gland tumors. Therefore, accurate differential diagnosis is essential for good prognosis and the prevention of complications due to misdiagnosis. Clinicians should have in-depth knowledge of diseases that may cause orofacial pain and know how to accurately assess structures with various modalities, such as CT and MRI. Diagnostic anesthesia can also play an important role in locating the cause of pain.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Korean Academy of Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine (Director of International Affairs); Korean Academy of Temporomandibular Disorders (Director of International Affairs); Korean Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine (Member of Board of Directors); Korean Society of Sleep Medicine (Member of Board of Directors); Asian Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine (Member); Asian Academy of Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorders (Member).

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cho SY, Kung WM S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Procacci P, Maresca M. Referred pain from somatic and visceral structures. Curr Rev Pain. 1999;3:96-99. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986;3:S1-S226. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Vecchiet L, Vecchiet J, Giamberardino MA. Referred Muscle Pain: Clinical and Pathophysiologic Aspects. Curr Rev Pain. 1999;3:489-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vecchiet L, Giamberardino M, Debigontina P. Referred pain from viscera-when the symptom persists despite the extinction of the visceral focus. Adv Pain Res Ther. 1992;20:101-110. |

| 5. | Okeson JP. The American academy of orofacial pain: Orofacial pain guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and management. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc., 2013: 12-14. |

| 6. | Okeson JP. Bell's Oral and Facial Pain. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc., 2014: 230-232. |

| 7. | Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:301-355. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Tai AX, Nayar VV. Update on Trigeminal Neuralgia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Phillips EJ, Sukasem C, Whirl-Carrillo M, Müller DJ, Dunnenberger HM, Chantratita W, Goldspiel B, Chen YT, Carleton BC, George AL, Mushiroda T, Klein T, Gammal RS, Pirmohamed M. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for HLA Genotype and Use of Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103:574-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chouinard G. Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65 Suppl 5:7-12. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yuan M, Zhou HY, Xiao ZL, Wang W, Li XL, Chen SJ, Yin XP, Xu LJ. Efficacy and Safety of Gabapentin vs. Carbamazepine in the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Meta-Analysis. Pain Pract. 2016;16:1083-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chua EK, List T, Tan KB, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17:21-28. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Okeson JP. Management of Temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. 7th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013. |

| 14. | Cummings M, Baldry P. Regional myofascial pain: diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:367-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Galán-Del-Río F, Alonso-Blanco C, Jiménez-García R, Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P. Referred pain from muscle trigger points in the masticatory and neck-shoulder musculature in women with temporomandibular disoders. J Pain. 2010;11:1295-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wright EF. Referred craniofacial pain patterns in patients with temporomandibular disorder. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:1307-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang XM, Zheng YQ, Zhang XM, Mai HQ, Zeng L, Liu X, Liu W, Zou H, Xu G. Diagnosis and management of skull base osteoradionecrosis after radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1626-1631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Linn J, Trantor I, Teo N, Thanigaivel R, Goss AN. The differential diagnosis of toothache from other orofacial pains in clinical practice. Aust Dent J. 2007;52:S100-S104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ehrmann EH, Tyas MJ. Cracked tooth syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and correlation between symptoms and post-extraction findings. Aust Dent J. 1990;35:105-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yatani H, Komiyama O, Matsuka Y, Wajima K, Muraoka W, Ikawa M, Sakamoto E, De Laat A, Heir GM. Systematic review and recommendations for nonodontogenic toothache. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:843-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vickers ER, Zakrzewska JM. Dental Causes of Orofacial Pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009; 14-19. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Hegarty AM, Zakrzewska JM. Differential diagnosis for orofacial pain, including sinusitis, TMD, trigeminal neuralgia. Dent Update. 2011;38:396-400, 402-403, 405-406 passim. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Little RE, Long CM, Loehrl TA, Poetker DM. Odontogenic sinusitis: A review of the current literature. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3:110-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | López Mesonero L, Pedraza Hueso MI, Herrero Velázquez S, Guerrero Peral AL. Infraorbital neuralgia: a diagnostic possibility in patients with zygomatic arch pain. Neurologia. 2014;29:381-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Maarbjerg S, Di Stefano G, Bendtsen L, Cruccu G. Trigeminal neuralgia - diagnosis and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:648-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Leclercq D, Thiebaut JB, Héran F. Trigeminal neuralgia. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:993-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rauhala K, Oikarinen KS, Raustia AM. Role of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) in facial pain: occlusion, muscle and TMJ pain. Cranio. 1999;17:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guzzo M, Locati LD, Prott FJ, Gatta G, McGurk M, Licitra L. Major and minor salivary gland tumors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:134-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hocwald E, Korkmaz H, Yoo GH, Adsay V, Shibuya TY, Abrams J, Jacobs JR. Prognostic factors in major salivary gland cancer. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1434-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lima RA, Tavares MR, Dias FL, Kligerman J, Nascimento MF, Barbosa MM, Cernea CR, Soares JR, Santos IC, Salviano S. Clinical prognostic factors in malignant parotid gland tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dupont JS Jr, Brown CE. The concurrency of temporal tendinitis with TMD. Cranio. 2012;30:131-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Iturriaga V, Fuentes F, Bornhardt T. Tendinitis of the temporalis muscle: Differential diagnosis and treatment. A case report. J Oral Res. 2016;5:82-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Shankland WE 2nd. Temporal tendinitis: a modified Levandoski panoramic analysis of 21 cases. Cranio. 2011;29:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bass E. Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork. 2012;5:14-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bressler HB, Markus M, Bressler RP, Friedman SN, Friedman L. Temporal tendinosis: A cause of chronic orofacial pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Matson MS. Pain in orofacial region associated with coronary insufficiency. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:284-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | de Oliveira Franco AC, de Siqueira JT, Mansur AJ. Bilateral facial pain from cardiac origin. A case report. Br Dent J. 2005;198:679-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | López-López J, Garcia-Vicente L, Jané-Salas E, Estrugo-Devesa A, Chimenos-Küstner E, Roca-Elias J. Orofacial pain of cardiac origin: review literature and clinical cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e538-e544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kikuta S, Dalip D, Loukas M, Iwanaga J, Tubbs RS. Jaw pain and myocardial ischemia: A review of potential neuroanatomical pathways. Clin Anat. 2019;32:476-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Maggioni F, Ruffatti S, Viaro F, Mainardi F, Lisotto C, Zanchin G. A case of posterior scleritis: differential diagnosis of ocular pain. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lan T, Liu X, Liang PS, Tao Q. Osteochondroma of the coronoid process: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2019;18:2270-2277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Autorino U, Borbon C, Malandrino MC, Gerbino G, Roccia F. Surgical Management of the Peripheral Osteoma of the Zygomatic Arch: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Surg. 2019;2019:6370816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |