Published online May 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1080

Peer-review started: December 27, 2018

First decision: January 30, 2019

Revised: February 25, 2019

Accepted: March 8, 2019

Article in press: March 8, 2019

Published online: May 6, 2019

Processing time: 132 Days and 20.7 Hours

Crizotinib-induce hepatotoxicity is rare and non-specific, and severe hepatotoxicity can develop into fatal liver failure. Herein, we report a case of fatal crizotinib-induced liver failure in a 37-year-old Asian patient.

The patient complained of dyspnea and upper abdominal pain for a week in August 2017. He was diagnosed with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma combined with multiple distant metastases. Crizotinib was initiated as a first-line treatment at a dosage of 250 mg twice daily. No adverse effects were seen until day 46. On day 55, he was admitted to the hospital with elevated liver enzymes aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (402 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (215 IU/L) and total bilirubin (145 μmol/L) and was diagnosed with crizotinib-induced fulminant liver failure. Despite crizotinib discontinuation and intensive supportive therapy, the level of AST (1075 IU/L), ALT (240 IU/L) and total bilirubin (233 μmol/L) continued to rapidly increase, and he died on day 60.

Physicians should be aware of the potential fatal adverse effects of crizotinib.

Core tip: Crizotinib-induce hepatotoxicity is rare and non-specific, and severe hepatotoxicity can develop to fatal liver failure. We report a case of fatal crizotinib-induced liver failure in a 37-year-old Asian patient with anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma combined with hepatic metastasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential fatal adverse effect of crizotinib. The King’s College Criteria and weekly monitoring of liver enzymes are necessary to diagnose and evaluate crizotinib-induced liver failure.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Xu YY, Chen Y, Li JN, Wang Y. Crizotinib-induced acute fatal liver failure in an Asian ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma patient with liver metastasis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(9): 1080-1086

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i9/1080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i9.1080

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, and it is the leading cause of cancer deaths. Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for nearly 80%-85% of lung cancers[1-5]. Most NSCLCs are unresectable and are already advanced upon diagnosis[3]. Molecular target therapy is effective for advanced NSCLC patients with related gene mutations. Some specific driver mutations in genes, including epidermal growth factor receptor, Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), have been identified in NSCLC[6]. ALK rearrangements are defined as a special molecular subtype of lung cancer and have been found in 5%-7% of NSCLC patients[7].

Crizotinib (XalkoriTM, Pfizer) is a multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets ALK, mesenchymal epithelial transition and c-ros oncogene 1 receptor tyrosine kinase. It was approved as a first-line therapy for the treatment of ALK-rearranged NSCLC by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011[8]. Crizotinib showed an improved survival rate compared to conventional chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC[9-11]. Common adverse effects of crizotinib have been reported, including vision disorders, gastrointestinal disturbances, electrocardiographic abnormalities, hypogonadism and hepatotoxicity. In five clinical trials (PROFILE 1001[12], 1005[13], 1007[10], 1014[14], 1029[15]), elevated aminotransferases were observed in 10%-38% of patients. Among them, 2%-16% of grade 3 or 4 patients had increased aminotransferase levels. However, most transaminase abnormality was reversible. Only 0.4% of patients exhibited irreversible hepatotoxicity, and two of them died[16]. Herein, we report a case of acute fatal crizotinib-induced liver failure when crizotinib was used as a first-line therapy for hepatic metastases in an Asian patient with lung adenocarcinoma. In addition, a literature review on crizotinib-induced hepatitis is presented.

A 37-year-old Asian man complained of dyspnea and upper abdominal pain for a week in August 2017.

The patient was admitted to our hospital in July 2017 due to complaints of fever and severe cough. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) identified a primary malignant nodule on the right lower lung lobe and mediastinal metastasis without liver metastasis. The patient underwent successful resection of the primary pulmonary nodules. Pathological examination showed a lung ade-nocarcinoma with echinoderm microtubule associated protein-like 4 and ALK rearrangement measured by fluorescence in situ hybridization. The patient did not receive chemotherapy after the operation due to his faint physical condition. In August 2017, he presented with dyspnea and upper abdomen pain for a week and returned to the hospital.

There was no history of past illness.

He was a non-smoker and non-drinker, also without history of drug allergy.

A physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and liver tenderness, and the Kar-nofsky performance status (KPS) was a score of 50.

On examination (day 1), a full panel of liver function tests revealed that the proth-rombin time (PT), serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were elevated, as follows: PT: 17.3 s (normal reference < 12.5 s), AST: 95 IU/L (normal reference < 34 IU/L), ALT: 55 IU/L (normal reference < 40 IU/L). However, the total bilirubin (10.6 μmol/L) level was normal (normal reference < 20.5 μmol/L). Biliary obstruction, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, ischemic hepatitis and hepatitis A, B or C virus infection were excluded. Serum tests were negative for Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes Simplex, hepatitis E virus antibodies and anti-mitochondrial smooth muscle. Other laboratory data were within normal limits, including serum ferritin, copper and ceruloplasmin.

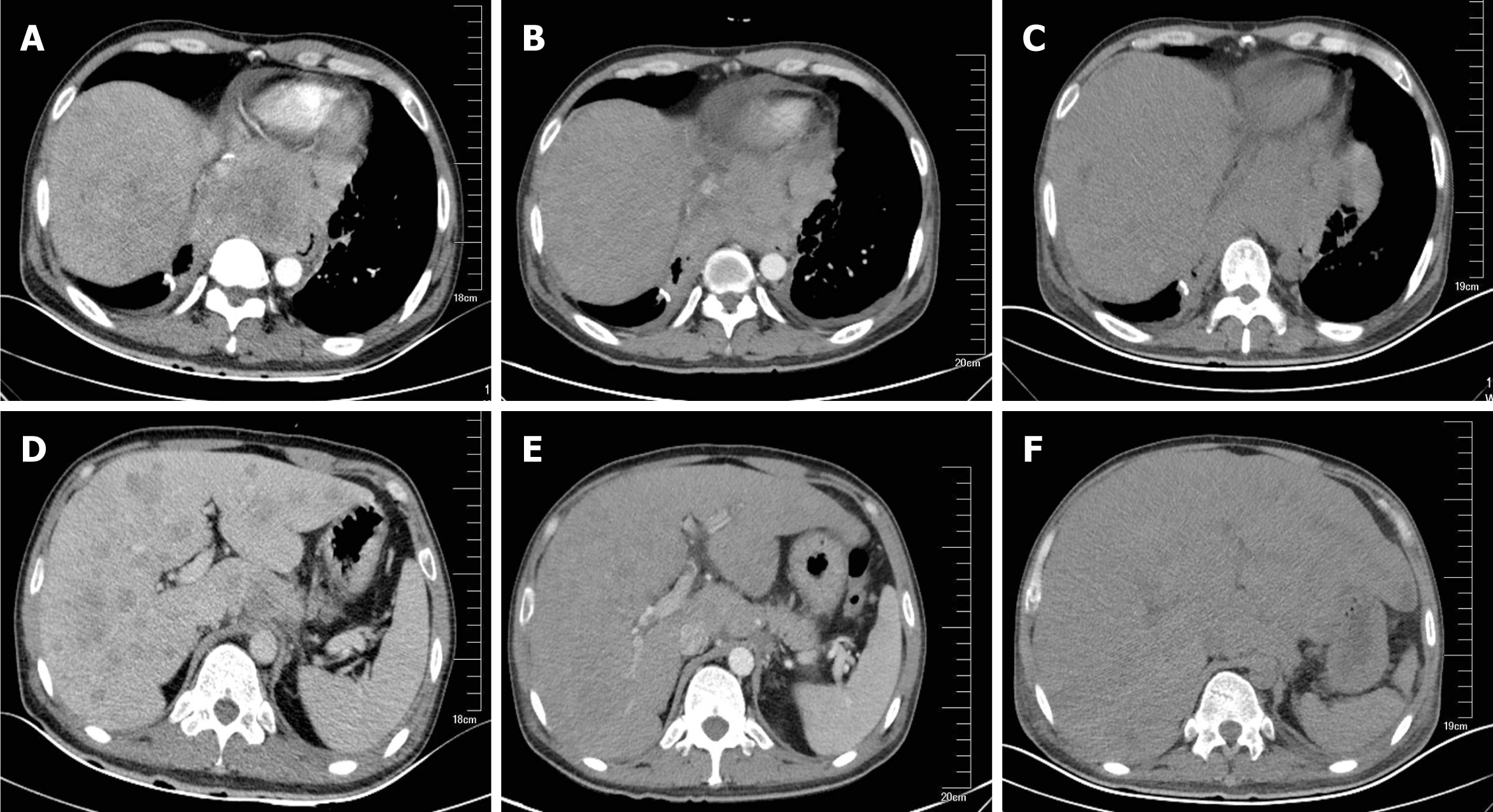

Chest and abdominal CT scans identified an 8.4 cm × 9.8 cm mediastinal metastatic lump and multiple hepatic metastases as a baseline (Figure 1A and D).

After consideration of the patient’s present history of lung adenocarcinoma and CT scans, the final diagnosis was advanced ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma with multiple distant metastases (cT1N2M1b, Stage IV).

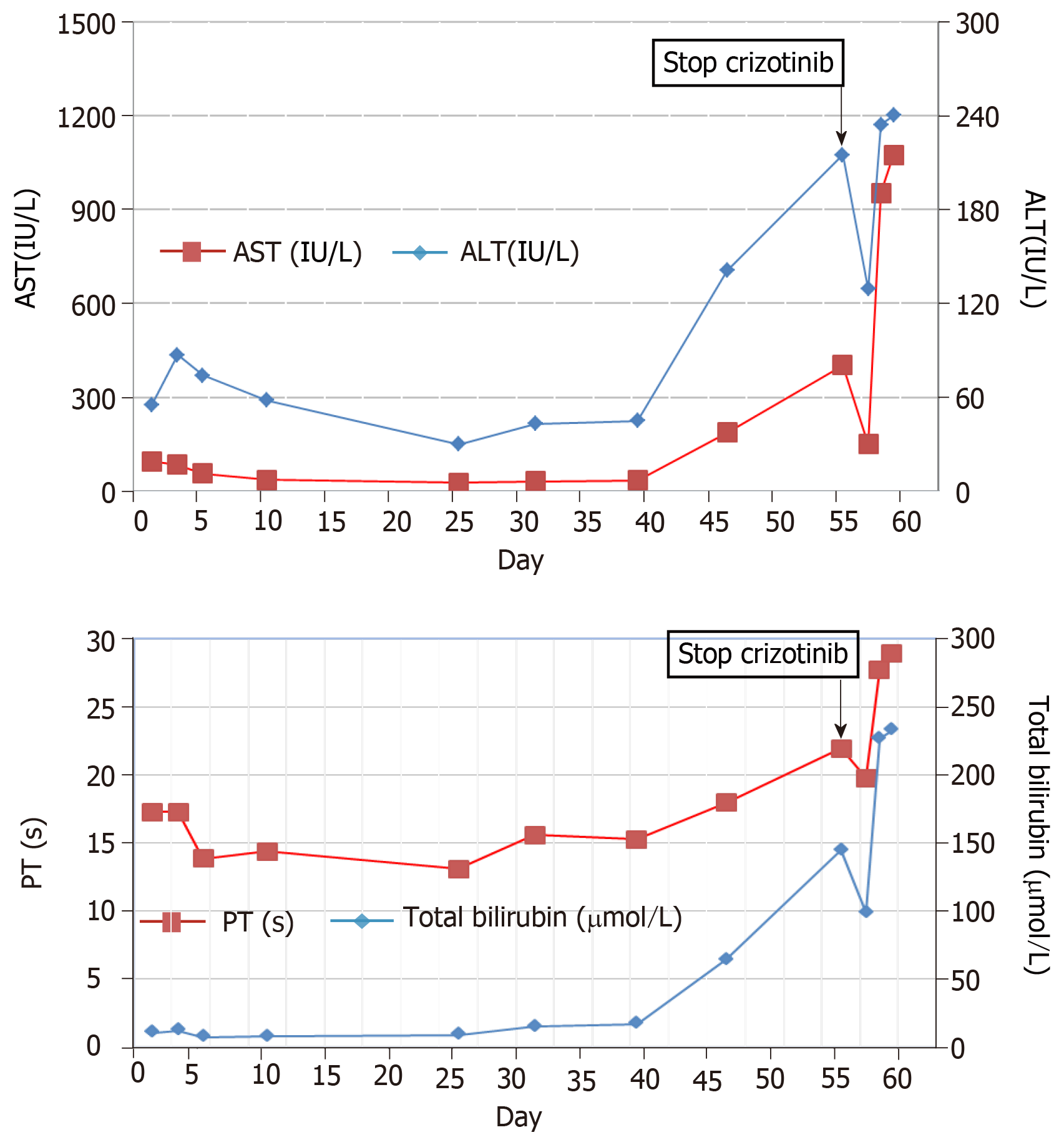

The patient received 250 mg oral crizotinib twice daily as first-line therapy and 456 mg polyene phosphatidylcholine capsules three times daily for transaminase elevation. On day 10, serum AST (36 IU/L) and ALT (58 IU/L) levels were obviously decreased. Clinical signs of dyspnea were relieved and upper abdomen pain disappeared by day 18. KPS was reevaluated, and the score was 90. Chest and abdominal CT scans identified the stable mediastinal lump and multiple hepatic nodules. On day 25, liver enzyme levels had decreased to normal values. On day 35, chest and abdominal CT scans revealed a slight decrease in volume of mediastinal and liver metastases (Figure 1B, 1E). The therapeutic effect was classified as stable disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. On day 46, the patient was found to have icteric sclera and abnormal liver enzyme levels during his outpatient follow-up, but he refused treatment. On day 55, he began to appear drow-sy but with normal vital signs. Physical examination showed icteric sclera and asterixis. Laboratory data indicated liver function impairment, as follows: AST: 402 IU/L, ALT: 215 IU/L, total bilirubin: 145 μmol/L; PT: 18 s. ALT level, AST level and total bilirubin were evaluated as toxicity grade 3. The plasma NH3 (63 μmol/L) level accumulated (9 < normal reference < 33 μmol/L). Chest CT scan showed that the mediastinal lump was unchanged (Figure 1C) and head CT scan was normal. However, abdominal CT scan revealed acute intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, massive ascites and an increase in liver volume by 20% with unvaried metastatic nodules (Figure 1F). According to the King’s College Criteria, fulminant liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy were diagnosed. Crizotinib-induced liver failure was strongly suspected, and crizotinib treatment was discontinued from the evening of day 55. The patient was given intensive treatments for acute hepatic failure, including lactulose against encephalopathy, prophylactic antibiotics, proton pump inhibitor, human albumin and plasma, according to the practice guidelines. On day 57, his disturbed consciousness improved, and the level of AST (150 IU/L), ALT (129 IU/L) and total bilirubin (99.1 μmol/L) decreased. Although these intensive therapies were continued, his liver function rapidly deteriorated, as follows: AST: 1075 IU/L, ALT: 240 IU/L, total bilirubin: 233 μmol/L; PT: 29 s, NH3: 163 μmol/L. The changes in AST, ALT and total bilirubin from day 1 to day 59 are shown in Figure 2. He went comatose on day 59.

On day 60, the patient died. Autopsy or liver biopsy could not be conducted.

This report describes the first case of fatal crizotinib-induced fulminant liver failure in an Asian patient with liver metastasis. Other causes of liver failure were eliminated, including hepatic metastasis, viral hepatitis infection, biliary obstruction, alcoholic liver disease and concomitant medication. In the beginning, the slightly increased transaminase levels decreased to normal levels after 25 d of oral crizotinib, which indicates that the improvement in liver function was closely related to crizotinib therapy for liver metastasis[17]. However, ALT and AST levels and liver volume suddenly increased on day 55. Although transaminase and total bilirubin levels decreased after two days of crizotinib discontinuation, it increased rapidly again over the next two days, which may have been caused by massive necrosis of liver cells. Based on these findings, crizotinib-induced acute liver injury was strongly suspected.

To better understand the current status of crizotinibinduced fulminant hepatitis, we reviewed and summarized the published literature (Table 1). Four cases of crizotinibinduced hepatitis have been reported, which occurred within a few months after crizotinib treatment. Among these patients, two of them died of hepatic enceph-alopathy caused by liver failure and one of them died of respiratory failure with carcinomatous pleurisy[18-21]. Consistent with these two cases, the patient in our report also died of crizotinib-induced fulminant liver failure. However, our case was an advanced lung cancer patient with liver metastasis, which is distinct from the reported cases. Thus, early diagnosis and treatment are critical for crizotinib-induced hepatotoxicity, which could help ALK-positive lung cancer patients to obtain survival benefits and avoid fatal events. Weekly liver function tests including transaminases and total bilirubin are insufficient to estimate sporadic crizotinib-induced hepatotoxicity. The King’s College Criteria was used to evaluate acute liver failure and poor prognosis. The sensitivity and the specificity of King’s College Criteria have been shown to be 68%-69% and 82%-92%, respectively[22]. Therefore, drug-induced liver dysfunction could be diagnosed early and accurately by using the King’s College Criteria. Altogether, the King’s College Criteria should also be used weekly to evaluate crizotinib-induced acute liver failure.

| Author | Therapy line | Initial dose | Liver injury | Occurrence time | Outcome |

| Ripault et al[18], 2013 | Not mentioned | 500 mg Qd | Acute hepatitis | Day 60 | Transaminases returned to normal |

| Sato et al[19], 2014 | First-line | 400 mg Qd | Fulminant hepatitis | Day 29 | Died of liver failure |

| Van Geel et al[20], 2016 | Second-line | 250 mg Bid | Fulminant liver failure | Day 24 | Died of liver failure |

| Yasuda et al[21], 2017 | Second-line | 250 mg Bid | Hepatitis | Day 16 | Died of respiratory failure |

| Present case | First-line | 250 mg Bid | Fulminant liver failure | Day 46 | Died of liver failure |

The mechanism of crizotinib-induced hepatotoxicity remains unclear. Crizotinib is extensively metabolized in the liver by CYP450 3A. Consequently, crizotinib and CYP450 3A inducers or inhibitors should be avoided at the same time so as not to increase plasma concentrations of crizotinib[23]. Moreover, Yasuda et al[21] have suggested that the underlying mechanism of hepatotoxicity is a partial allergic reac-tion to crizotinib or its metabolite. Oral desensitization could be considered a viable option after crizotinib-induced hepatitis. In addition, as a novel ALK inhibitor, ceritinib could be also used as an alternative agent when crizotinib causes hepatitis[24]. Generally, the initial dose of crizotinib was given at 250 mg twice-daily, which does not account for the patient’s age, sex, race, body weight, or hepatic function impair-ment. Therefore, physicians should be aware of serious adverse reactions caused by individual differences[25].

This study indicates that crizotinib can cause fulminant liver failure in lung cancer patient with liver metastasis. Clinicians should be highly aware of the potential fatal adverse effect induced by crizotinib, especially for patients with liver metastasis. Liver enzyme testing should be carried out at least once a week during the first 2 mo of crizotinib treatment. It is strongly suggested that the King’s College Criteria be used to prevent acute liver failure during crizotinib administration in the clinic.

| 1. | Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1754] [Cited by in RCA: 1915] [Article Influence: 119.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wen M, Wang X, Sun Y, Xia J, Fan L, Xing H, Zhang Z, Li X. Detection of EML4-ALK fusion gene and features associated with EGFR mutations in Chinese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:1989-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9215] [Cited by in RCA: 9876] [Article Influence: 759.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 4. | Zhu YC, Xu CW, Ye XQ, Yin MX, Zhang JX, Du KQ, Zhang ZH, Hu J. Lung cancer with concurrent EGFR mutation and ROS1 rearrangement: a case report and review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:4301-4305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Padma S, Sundaram PS, George S. Role of positron emission tomography computed tomography in carcinoma lung evaluation. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 822] [Cited by in RCA: 931] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Camidge DR, Doebele RC. Treating ALK-positive lung cancer--early successes and future challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:268-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ou SH. Crizotinib: a novel and first-in-class multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearranged non-small cell lung cancer and beyond. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:471-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, Iafrate AJ, Varella-Garcia M, Fox SB, Riely GJ, Solomon B, Ou SH, Kim DW, Salgia R, Fidias P, Engelman JA, Gandhi L, Jänne PA, Costa DB, Shapiro GI, Lorusso P, Ruffner K, Stephenson P, Tang Y, Wilner K, Clark JW, Shaw AT. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results from a phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1011-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 999] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 72.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn MJ, De Pas T, Besse B, Solomon BJ, Blackhall F, Wu YL, Thomas M, O'Byrne KJ, Moro-Sibilot D, Camidge DR, Mok T, Hirsh V, Riely GJ, Iyer S, Tassell V, Polli A, Wilner KD, Jänne PA. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2534] [Cited by in RCA: 2735] [Article Influence: 210.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Solomon BJ, Riely GJ, Gainor J, Engelman JA, Shapiro GI, Costa DB, Ou SH, Butaney M, Salgia R, Maki RG, Varella-Garcia M, Doebele RC, Bang YJ, Kulig K, Selaru P, Tang Y, Wilner KD, Kwak EL, Clark JW, Iafrate AJ, Camidge DR. Effect of crizotinib on overall survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring ALK gene rearrangement: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1004-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 709] [Cited by in RCA: 721] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou SH, Dezube BJ, Jänne PA, Costa DB, Varella-Garcia M, Kim WH, Lynch TJ, Fidias P, Stubbs H, Engelman JA, Sequist LV, Tan W, Gandhi L, Mino-Kenudson M, Wei GC, Shreeve SM, Ratain MJ, Settleman J, Christensen JG, Haber DA, Wilner K, Salgia R, Shapiro GI, Clark JW, Iafrate AJ. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3613] [Cited by in RCA: 3575] [Article Influence: 223.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blackhall F, Ross Camidge D, Shaw AT, Soria JC, Solomon BJ, Mok T, Hirsh V, Jänne PA, Shi Y, Yang PC, Pas T, Hida T, Carpeño JC, Lanzalone S, Polli A, Iyer S, Reisman A, Wilner KD, Kim DW. Final results of the large-scale multinational trial PROFILE 1005: efficacy and safety of crizotinib in previously treated patients with advanced/metastatic ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, Cappuzzo F, Paolini J, Usari T, Iyer S, Reisman A, Wilner KD, Tursi J, Blackhall F; PROFILE 1014 Investigators. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2160] [Cited by in RCA: 2541] [Article Influence: 211.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu YL, Lu S, Lu Y, Zhou J, Shi YK, Sriuranpong V, Ho JCM, Ong CK, Tsai CM, Chung CH, Wilner KD, Tang Y, Masters ET, Selaru P, Mok TS. Results of PROFILE 1029, a Phase III Comparison of First-Line Crizotinib versus Chemotherapy in East Asian Patients with ALK-Positive Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1539-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Girard N, Audigier-Valette C, Cortot AB, Mennecier B, Debieuvre D, Planchard D, Zalcman G, Moro-Sibilot D, Cadranel J, Barlési F. ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancers: how best to optimize the safety of crizotinib in clinical practice? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2015;15:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liang W, He Q, Chen Y, Chuai S, Yin W, Wang W, Peng G, Zhou C, He J. Metastatic EML4-ALK fusion detected by circulating DNA genotyping in an EGFR-mutated NSCLC patient and successful management by adding ALK inhibitors: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ripault MP, Pinzani V, Fayolle V, Pageaux GP, Larrey D. Crizotinib-induced acute hepatitis: first case with relapse after reintroduction with reduced dose. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:e21-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sato Y, Fujimoto D, Shibata Y, Seo R, Suginoshita Y, Imai Y, Tomii K. Fulminant hepatitis following crizotinib administration for ALK-positive non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:872-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Geel RM, Hendrikx JJ, Vahl JE, van Leerdam ME, van den Broek D, Huitema AD, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH, Burgers SA. Crizotinib-induced fatal fulminant liver failure. Lung Cancer. 2016;93:17-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yasuda Y, Nishikawa Y, Sakamori Y, Terao M, Hashimoto K, Funazo T, Nomizo T, Tsuji T, Yoshida H, Nagai H, Ozasa H, Hirai T, Kim YH. Successful oral desensitization with crizotinib after crizotinib-induced hepatitis in an anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer patient: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:295-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mishra A, Rustgi V. Prognostic Models in Acute Liver Failure. Clin Liver Dis. 2018;22:375-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yamazaki S, Johnson TR, Smith BJ. Prediction of Drug-Drug Interactions with Crizotinib as the CYP3A Substrate Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:1417-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sassier M, Mennecier B, Gschwend A, Rein M, Coquerel A, Humbert X, Alexandre J, Fedrizzi S, Gervais R. Successful treatment with ceritinib after crizotinib induced hepatitis. Lung Cancer. 2016;95:15-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang E, Nickens DJ, Bello A, Khosravan R, Amantea M, Wilner KD, Parivar K, Tan W. Clinical Implications of the Pharmacokinetics of Crizotinib in Populations of Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5722-5728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Coskun A S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ