Published online Mar 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i5.676

Peer-review started: June 20, 2018

First decision: July 8, 2018

Revised: February 6, 2019

Accepted: February 18, 2019

Article in press: February 18, 2019

Published online: March 6, 2019

Processing time: 259 Days and 7.8 Hours

Cystic adenomyosis is a special type of adenomyosis. Its clinical manifestations lack specificity. Pelvic ultrasound and nuclear magnetic resonance imaging can help clarify the diagnosis. Because cystic uterine adenomyosis is rare in clinical work, it can be easily misdiagnosed or its diagnosis can be missed. Early surgical treatment and postoperative drug treatment can alleviate dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, anemia, and other symptoms.

Two cases complained about abnormal vaginal bleeding and were diagnosed with intrauterine cystic adenomyosis by gynecological ultrasound and pathological examination. The clinical manifestations included dysmenorrhea, hypermenorrhea, and a history of cesarean section. Both cases underwent a surgery, and chocolate-like liquid was released from the cystic mass in the uterus and the manifestations were relieved.

Intrauterine cystic adenomyosis could be diagnosed by pathological examination and treated by hysterectomy or hystscopy to release the liquid inside.

Core tip: Because cystic uterine adenomyosis is rare in clinical work, it is easy to misdiagnose it or miss its diagnosis. We present two cases of intrauterine cystic adenomyosis that were recently treated at our department to explore its clinical features and treatment options so as to provide a reference for the early diagnosis and rational treatment of the disease.

- Citation: Fan YY, Liu YN, Li J, Fu Y. Intrauterine cystic adenomyosis: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(5): 676-683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i5/676.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i5.676

Adenomyosis refers to a common gynecological disease wherein the endometrial gland or stroma appears in the myometrium and is accompanied by compensatory hypertrophy and proliferation of peripheral smooth muscle cells. The etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear. Currently, studies suggest that adenomyosis belongs to the junctional zone (JZ) lesions, also known as subintimal muscle, located between the endometrium and extrauterine myometrium, which shows cyclical variation owing to the effect of estrogen and progesterone. When the endometrial zona basalis is damaged, the endometrium directly invades the adjacent JZ, resulting in diffuse or limited thickening of JZ and adenomyosis formation. Imaging changes of JZ lesions detected by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have become reliable indicators for clinically diagnosing adenomyosis[1,2]. Cystic adenomyosis, also known as cystic adenomyoma or adenomyotic cyst, is a special type of adenomyosis, which is a cystic structure lining the endometrium and covered with the uterine smooth muscle, containing old blood cyst fluid. Most of the case reports of cystic adenomyosis revealed that the lesions are located in the uterine muscular wall or subserosa.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We reviewed two cases of intrauterine cystic adenomyosis recently treated at our department and explored the clinical features and treatment options to provide a reference for the early diagnosis and rational treatment of the disease. The study was reviewed and approved by the First Hospital of Jilin University Institutional Review Board. All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

A 36-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital owing to an increase in menstrual blood volume and abnormal echo in the uterine cavity for 7 months.

Since September 2016, the patient’s menstrual period was extended to 6 d without any significant cause, and the menstrual blood volume was increased two-fold of the previous amount. She was admitted to a local county hospital. Doppler ultrasound examination revealed an abnormal intrauterine echo; thus, the physician suggested a dilation and curettage of the uterus, which she rejected. In October 2016, she found that the increase in menstrual blood volume was obviously aggravated, reaching about three times of the ordinary volume; then, she underwent Doppler ultrasound examination at the local hospital again. The results showed an intrauterine mildly strong echo (21 mm × 13 mm). The pathological results after curettage revealed the endometrium at the proliferative phase. After her menstrual period, she obtained a recheck of gynecological ultrasound, which showed the endometrial thickness to be 12 mm. Then, she was asked to be followed. Two months before hospitalization, her dysmenorrhea was progressively aggravated, and the bleeding was not changed, presenting as hypogastrium cramps at the menstrual period.

Her previous history included undergoing a cesarean section at a local hospital 15 years ago with three induced abortions thereafter.

She had smooth vagina and soft mucous membrane, normal and smooth cervix, and anterior uterine body with a size of about 7.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 6.0 cm, which was hard and tough with normal uterine mobility but without tenderness. No abnormality or tenderness was noted in the double appendage area; vaginal secretions were white and less, without abnormal flavor.

Routine blood test (October 25, 2016) showed a WBC count of 6.32 × 109/L, percentage of neutrophils of 73%, RBC count of 3.57 × 1012/L, hemoglobin concentration of 125 g/L, and platelet count of 261 × 109/L. Gynecological ultrasound revealed an endometrial thickness of 20 mm and a mixed partially strong echo of 31 mm × 24 mm × 24 mm in the uterus. The pathological report after the uterine curettage at a local hospital (Pathology No. 39869) on October 28, 2016 showed a broken uterine endometrium at the proliferative phase.

The gynecological ultrasound examination on April 6, 2017 at our hospital revealed the following: the uterine body was anterior, measuring 61 mm × 55 mm × 54 mm, the shape of the uterus was symmetrical, and the velamen was smooth; two low echogenic areas were detected in the smooth muscle wall; and the larger one with clear border was located in the back wall, measuring 11 mm × 8 mm, although the uterine cavity line was unclear. The endometrial thickness was 20 mm, with an uneven echo. A mixed partially strong echogenic area of 31 mm × 24 mm × 24 mm in the uterus with blood flow was found, in which there was an irregular liquid anechoic area with a size of 20 mm × 18 mm × 16 mm and the liquid content was not clear. The size and echo of the ovaries were normal. She was clinically diagnosed with an intrauterine lesion (endometrial polyp or cystic adenomyosis), adenomyosis combined with small myoma, and scarred uterus after caesarean section.

After admission, she underwent hysteroscopy under the guidance of ultrasound with general anesthesia. During the operation, a neoplasm measuring about 4.0 cm × 3.0 cm × 4.0 cm was found, which was located in the anterior wall from the base of the uterus to near the isthmus with a length of 3.0 cm and had mulberry-like surface and thick pedicle. The endometrium was pink and white and diffusely proliferated. The opening of the bilateral fallopian tubes could be seen. The neoplasm was opened using an annular electrode; then, chocolate-like liquid flowing out from it was observed. The neoplasm was resected from the pedicle using the annular electrode, and a Mirena ring was placed in the uterus at the same time. Postoperative pathological examination (Pathology No. 614984C) revealed that the endometrium had secretory changes and adenomyosis in the uterine cavity. Postoperatively, intramuscular injections of 3.75 mg diphereline once every 28 days for a total of three times were administered to the patient. Two months after the operation, the patient’s return visit showed obviously alleviated dysmenorrhea. Gynecological Doppler ultrasound examination revealed that the uterus had notably shrunk compared with its previous size and the intrauterine Mirena ring was in normal position.

A 39-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital owing to relapse of uterine fibroids after undergoing hysteromyomectomy twice.

On February 19, 2017, the patient found continuous heavy vaginal bleeding in dark red color. Thus, on March 5, 2017, she visited a physician at a hospital in Changchun City. Gynecological Doppler ultrasound examination revealed relapse of uterine fibroids. To confirm the result, she visited physicians at our hospital and other hospitals in Changchun and obtained the same diagnosis of recurrent uterine fibroids and possible degeneration. Surgery was suggested. Then, she was admitted to our hospital due to the uterine fibroids with a moderate amount of bloody secretions without abnormal flavor.

The patient underwent hysteromyomectomy at a hospital in Changchun, China in 2007. She self-reported that three uterine fibroids, measuring 2 cm in diameter, were removed, but no follow-up was conducted after the operation. In 2012, a physical examination at a hospital in Changchun showed relapse of uterine fibroids, but pregnancy was also noted. Hence, in 2013, she underwent a cesarean section and intraoperative hysteromyomectomy at the same time at a hospital in Changchun City. She self-reported that two uterine fibroids were resected, and no postoperative review was conducted.

Smooth vagina and soft mucous membrane; normal and smooth cervix.

Routine blood test (March 11, 2017) showed a WBC count of 13.12 × 109/L, percentage of neutrophils of 0.89, RBC count of 4.20 × 1012/L, hemoglobin concentration of 97 g/L, and platelet count of 482 × 109/L. Serum human chorionic gonadotropin level (March 11, 2017) was 2.39 mIU/mL. The rechecked routine blood test on admission showed a WBC count of 6.14 × 109/L, percentage of neutrophils of 0.81, RBC count of 4.19 × 1012/L, hemoglobin concentration of 97 g/L, and platelet count of 453/109/L. The D-dimer level on admission was 3597.00 μg/L. Screening of female tumor markers revealed a carbohydrate antigen (CA)-125 level of 1212.00 U/mL and CA-72 level of 416.51 U/mL; the remaining items were normal. After 3 days of anti-infective treatment, the blood test was reviewed, showing a normal WBC count, hemoglobin concentration of 86 g/L, D-dimer level of 3172.00 ug/L, and CA-125 level of 775.90 U/mL.

Gynecological examination revealed normal vulva development, smooth vagina and soft mucous membrane, normal and smooth cervix with a small amount of blood flowing out, and the uterine body at the anterior position larger than fist and round shaped; the right posterior wall of the uterus was convex, hard, and tough, but the mobility was not normal, without tenderness. Neither abnormality nor tenderness was noted in the bilateral appendage area. Gynecological Doppler ultrasound examination performed on March 11, 2017 revealed the anterior uterus, which had a symmetrical shape and smooth contours with a size of 65 mm × 60 mm × 59 mm. The muscle wall echo was rough and uneven. One low echogenic area of 56 mm × 44 mm at the right posterior wall was found, with an uneven internal echo and peripheral blood flow, in which there were two irregular liquid anechoic areas, with the larger being 40 mm × 29 mm × 22 mm and protruding to the uterine cavity. The uterine cavity line was not clear, and the endometrium was 17 mm thick, with an uneven echo. The size and echo of the ovaries were normal. Pelvis routine scan + enhancement + diffusion by 3.0 T MRI revealed the presence of occupying lesions at the base and posterior wall of the uterus, suggesting possible uterine fibroids with degeneration, multiple small cysts in the cervix, and small amount of fluids in the pelvic cavity. A clinical diagnosis of recurrent uterine fibroids (with the possibility of degeneration), adenomyosis, postoperation of two hysteromyomectomies, postoperative scarred uterus of cesarean section, pelvic adhesion, and mild anemia was made. After appropriately communicating with the patient, hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, and lysis of pelvic adhesions were performed on March 17, 2017. Intraoperative findings were partial intestinal canal adhering to the abdominal wall, mesosigmoid adhering to the left appendage and lateral pelvic wall, and anterior rectal wall mesenterium extensively adhering to the posterior wall of uterine body; there was a small amount of pink ascites in the pelvic cavity; the uterine body was spherically enlarged (about 8 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm) and hard, and the posterior wall of the uterus was evaginated; fibrinoid inflammatory exudation was found on the surface of the uterine body. Cyst with a diameter of about 2 cm could be seen in the bilateral ovaries. The appearance of the bilateral oviducts was normal. After the uterus was opened, a cystic mass with a size of about 5 cm × 4 cm × 4 cm was found in the uterus, attached to the posterior wall with a pedicle. The cystic wall thickness was about 0.8 cm, with a smooth and yellow surface, containing chocolate-like liquid. Intraoperative pathology (Pathology No. 611231C) revealed adenomyosis. Postoperative pathology (Pathology No. 611231C) revealed adenomyosis, endometrium at the proliferative phase, chronic cervicitis, and no obvious lesions in the bilateral oviducts. Cytological examination of ascites revealed no cancer cells. Five days after the operation, routine blood test showed a WBC count of 3.41 × 109/L, percentage of neutrophils of 0.54, RBC count of 4.37 × 1012/L, hemoglobin concentration of 106 g/L, platelet count of 359 × 109/L, and CA-125 level of 356.50 U/mL. Two months after the surgery, the review showed the vaginal cuff healing well and a normal CA-125 level.

Intrauterine cystic adenomyosis.

Operation (hysteroscopy and hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy).

Both of them were cured.

In 1908, Cullen[3] first described the formation of capsular space in the submucosa of patients with adenomyosis, and the cysts were lined with normal endometrial glands, filled with chocolate-like fluid. In 1990, Parulekar[4] reported the first case of cystic adenomyosis, and in 1996, Tamura et al[5] reported the first case of cystic uterine adenomyosis in an adolescent. Current clinical data show that the age span of the patients with cystic adenomyosis is broad, ranging from 13 to 54 years, although it is common in adolescent and adult women aged < 30 years. Its clinical manifestation is similar to that of typical uterine adenomyosis, mainly presenting as severe dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and chronic pelvic pain. A small number of patients have no clinical symptoms. According to the onset age, cystic adenomyosis can be divided into the adolescent and adult types[6,7]. There are two sets of diagnostic criteria for the adolescent type. The diagnostic criteria include the following: (1) the age is < 30 years; (2) the cyst is > 1 cm in diameter, and the capsular space is independent of the uterine cavity and surrounded by hyperplastic smooth muscle tissue; and (3) severe dysmenorrhea develops early. The diagnostic criteria proposed by Chun[8] in 2011 are as follows: (1) the onset age is < 18 years, or severe dysmenorrhea develops within 5 years after the onset of menarche; (2) there is no history of operation in the uterus; and (3) the diameter of the cystic cavity is > 5 mm. Both sets of diagnostic criteria have their own advantages and disadvantages, and the former is more consistent with the clinical practice in terms of the standard of histopathology, while the latter is more accurate in the definition of age. The diagnostic criteria for adult type are more obscure, generally referring to those with the onset age of > 30 years and most with a history of uterine operation.

In this study, both patients presented with dysmenorrhea, hypermenorrhea, and a history of cesarean section, and the second patient had a history of hysteromyomectomy twice, suggesting that the clinical manifestations and pathogenesis of intrauterine cystic adenomyosis are similar to those which originate from other parts.

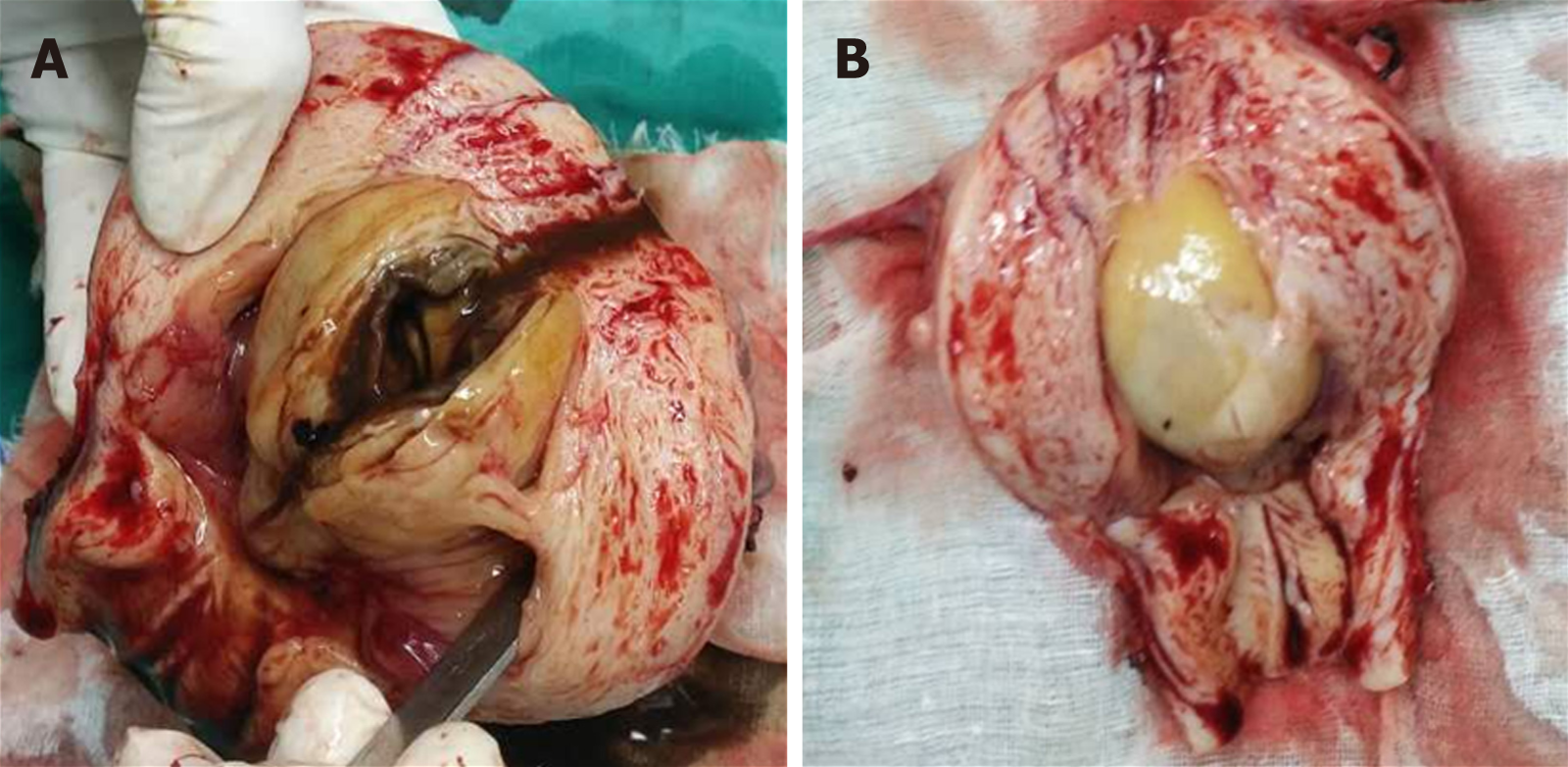

In this study, both cases showed an intrauterine mass with a diameter of 3–5 cm (Figure 1). The surface of the mass was red mulberry shaped or yellowish-white and smooth. As the mass was opened, chocolate-like liquid flowed out. The inner wall of the cyst was smooth, with a thickness of 0.5–0.8 cm. The pathological examination revealed that the cystic wall was composed of arranged endometrial glands and stroma and covered with hyperplastic muscular tissues.

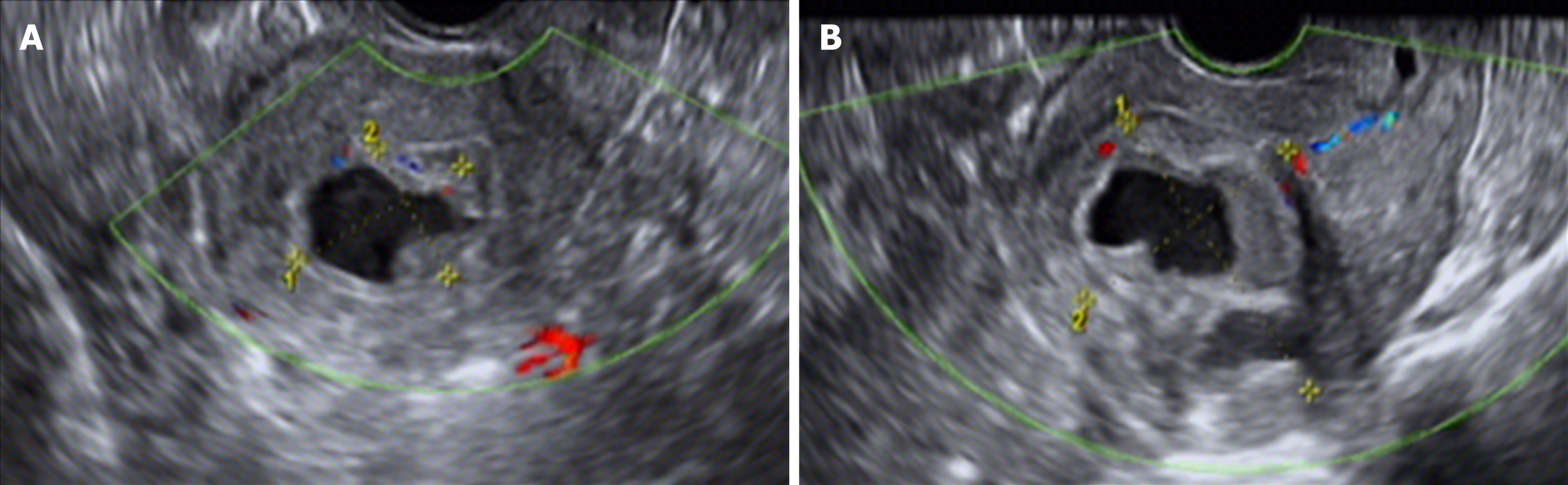

Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound examination is convenient and economical for screening intrauterine cystic adenomyosis (Figure 2). In this study, ultrasound showed low echo masses in the uterine cavity or muscle wall intruding into the uterine cavity, with irregular liquid echopattern inside. There were dense strong echo spots in the liquid echopattern and dotted distribution of blood flow signals. The typical sonographic findings of endometrial polyps are as follows: regularly shaped lesions with a high-level echo and strong echo halo around the lesions can be seen in the uterine cavity, and cysts can be seen in the polyp. Color Doppler can display the typical single blood flow signal supplying the endometrial polyps.

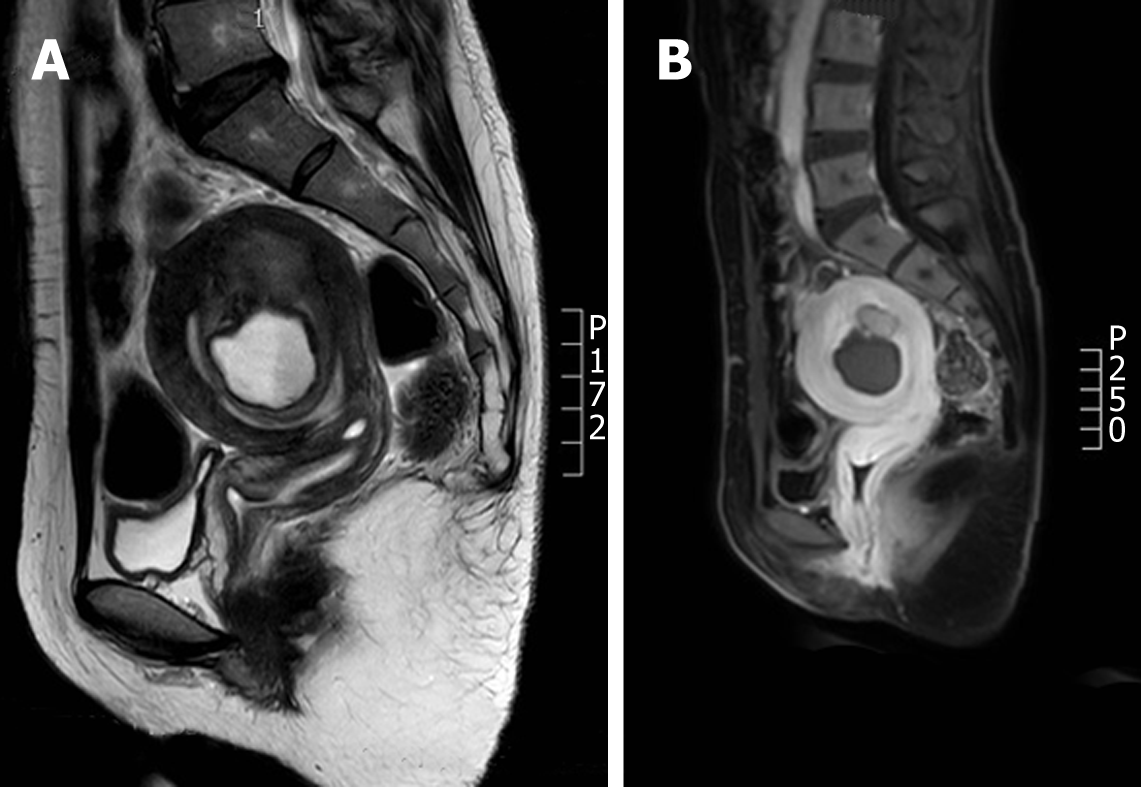

Nuclear MRI is a commonly used method for the clinical diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis. The T2W1 characteristics of adenomyosis include the broadening JZ and ill-defined shadows mixed by hypointensity and hyperintensity[9]. In this study, an intrauterine thick-walled cyst was displayed in the MRI scan, which showed hyperintensity in T1 weighted image, moderate to high intensity in T2 weighted image, and low intensity in the edge (Figure 3). MRI plays a vital role in the differential diagnosis between adenomyosis and uterine fibroid degeneration[10]. The characteristics of uterine fibroid hyalinosis in MRI are moderate intensity in TIW1 and low intensity in T2W1, while uterine fibroids mucinous degeneration has a characteristic of high intensity in T2W1, sometimes characterized by multiple patches, without reinforcement in the enhanced scan. MRI can not only reflect the characteristic signal of the tumor to identify the position and size but also identify the complex uterine malformations, which is the best diagnostic method for the disease[11].

The specificity and sensitivity of serum CA-125 level in the diagnosis of cystic uterine adenomyosis are low, but an increased CA-125 level is helpful in the differential diagnosis of the disease from endometrial polyps and uterine myoma degeneration. Takeuchi et al[12] reported that the CA-125 level can be from normal to > 500 U/mL in patients. In this study, CA-125 level was normal in one case and as high as 1212.00 U/mL in the other case. The reasons may be as follows: first, since the intrauterine lesion was huge, and a large amount of CA-125 produced by the lining endometrial epithelium and interstitial cells in the lesion was released into the blood, the diffuse type of uterine adenomyosis had an elevated CA-125 level; second, during the operation, a large area of inflammatory cellulosic exudation was found on the surface of the uterus, which was considered as complicated with pelvic inflammatory disease, leading to a significant increase in CA-125 level.

The therapeutic principle for cystic adenomyosis is radical resection of the lesions, promoting fertility and preventing recurrence. The therapeutic modality can vary according to the onset age, request of fertility, location and size of the lesion, and symptoms[13].

Hysteroscopic resection of lesions is preferred for the treatment of intrauterine cystic adenomyosis[14]. In this study, one patient underwent hysteroscopic resection and intrauterine Mirena ring placement at the same time. It not only effectively alleviated her symptoms of dysmenorrhea and increased menstrual volume but also led to endometrial atrophy by local release of efficient progestin in the uterine cavity, so as to effectively prevent disease recurrence. However, if the cyst is too large to perform hysteroscopic surgery, total hysterectomy can be considered if the patient has no fertility request[15]

Although cystic adenomyosis is common, the location of cystic adenomyosis in the uterine cavity is rare. The case report would bring more attention on the diagnosis. However, these two cases were of different phases and not comparable, which needs more cases to be collected to gain evidenced value.

In conclusion, cystic adenomyosis is a rare type of adenomyosis of the uterus, and intrauterine cystic adenomyosis has even been less reported. Owing to the clinicians’ low understanding of the disease, it is easy to be misdiagnosed or missed in the diagnosis. At present, there is no clinical data with large samples to confirm its prognosis, influence on fertility, and whether postoperative medication can effectively prevent its recurrence. How to detect and treat intrauterine cystic adenomyosis effectively and develop effective methods to prevent its recurrence is an urgent problem that needs to be resolved.

Intrauterine cystic adenomyosis could be treated by hysterectomy or by hystscopy.

| 1. | Porpora MG, Vinci V, De Vito C, Migliara G, Anastasi E, Ticino A, Resta S, Catalano C, Benedetti Panici P, Manganaro L. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Predicting Pain Related to Endometriosis: A Preliminary Study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:661-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tsui KH, Lee WL, Chen CY, Sheu BC, Yen MS, Chang TC, Wang PH. Medical treatment for adenomyosis and/or adenomyoma. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:459-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cullen TS. Adenomyoma of the uterus. Philadelphia: Saunders 1908; 128-149. |

| 4. | Parulekar SV. Cystic degeneration in an adenomyoma (a case report). J Postgrad Med. 1990;36:46-47. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Tamura M, Fukaya T, Takaya R, Ip CW, Yajima A. Juvenile adenomyotic cyst of the corpus uteri with dysmenorrhea. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1996;178:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manchanda R, Manchanda P, Meena J. Cystic Adenomyosis. Hysteroscopy. 2018;479-492. |

| 7. | Brosens I, Gordts S, Habiba M, Benagiano G. Uterine Cystic Adenomyosis: A Disease of Younger Women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:420-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chun SS, Hong DG, Seong WJ, Choi MH, Lee TH. Juvenile cystic adenomyoma in a 19-year-old woman: a case report with a proposal for new diagnostic criteria. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:771-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stoelinga B, Hehenkamp WJK, Nieuwenhuis LL, Conijn MMA, van Waesberghe JHTM, Brölmann HAM, Huirne JAF. Accuracy and Reproducibility of Sonoelastography for the Assessment of Fibroids and Adenomyosis, with Magnetic Resonance Imaging as Reference Standard. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44:1654-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Agostinho L, Cruz R, Osório F, Alves J, Setúbal A, Guerra A. MRI for adenomyosis: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2017;8:549-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Krentel H, Cezar C, Becker S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Tanos V, Wallwiener M, De Wilde RL. From Clinical Symptoms to MR Imaging: Diagnostic Steps in Adenomyosis. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:1514029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takeuchi H, Kitade M, Kikuchi I, Kumakiri J, Kuroda K, Jinushi M. Diagnosis, laparoscopic management, and histopathologic findings of juvenile cystic adenomyoma: a review of nine cases. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:862-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oliveira MAP, Crispi CP, Brollo LC, Crispi CP, De Wilde RL. Surgery in adenomyosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297:581-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Levgur M. Therapeutic options for adenomyosis: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ascher-Walsh CJ, Tu JL, Du Y, Blanco JS. Location of adenomyosis in total hysterectomy specimens. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:360-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Cosmi E, Khajehei M, Zhang XQ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Bian YN