Published online Dec 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4407

Peer-review started: September 14, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Revised: November 3, 2019

Accepted: November 15, 2019

Article in press: November 15, 2019

Published online: December 26, 2019

Processing time: 101 Days and 15.5 Hours

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is not an uncommon complication. Acute UGIB caused by Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) is usually a dire situation with massive bleeding and hemodynamic instability. Acute UGIB caused by MWS after an AMI has not been previously reported.

A 57-year-old man with acute inferior wall ST elevation myocardial infarction underwent a primary coronary intervention of the acutely occluded right coronary artery. Six hours after the intervention, the patient had a severe UGIB, followed by vomiting. His hemoglobin level dropped from 15.3 g/dL to 9.7 g/dL. In addition to blood transfusion and a gastric acid inhibition treatment, early endoscopy was employed and MWS was diagnosed. Bleeding was stopped by endoscopic placement of titanium clips.

Bleeding complications after stent implantation can pose a dilemma. MWS is a rare but severe cause of acute UGIB after an AMI that requires an early endoscopic diagnosis and a hemoclip intervention to stop bleeding.

Core tip: Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) after an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is not an uncommon complication. Acute UGIB caused by Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) after an AMI has not been previously reported. Here we report the diagnosis and management of a 57-year-old AMI patient who developed UGIB caused by MWS shortly after the primary coronary intervention. In addition to blood transfusion and acid inhibition treatment, early endoscopy was employed, and MWS was diagnosed. Bleeding was stopped by endoscopic hemoclip intervention with close monitoring of the hemodynamic status.

- Citation: Du BB, Wang XT, Li XD, Li PP, Chen WW, Li SM, Yang P. Treatment of severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by Mallory-Weiss syndrome after primary coronary intervention for acute inferior wall myocardial infarction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(24): 4407-4413

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i24/4407.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4407

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is related to an increased incidence (8.9%) of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB)[1]. The addition of this comorbidity raises in-hospital and long-term mortality to 25%-35%[1-3]. However, due to a paucity of studies on this topic and the need for interdisciplinary collaboration, patients may not receive proper management.

A bleeding complication after a coronary intervention is a dilemma for doctors. Continuing platelet inhibition therapy increases the risk of hemorrhagic shock, while interruption of antiplatelet treatment increases the risk of stent thrombosis. Both considerations should be carefully balanced after reviewing individual facts and the guidelines. In addition, acute UGIB and AMI can both cause hemodynamic instability and increase mortality[4,5].

Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) is a rare disease that can cause severe UGIB due to esophageal and cardial mucosal tears[6]. Here, we report the treatment of a 57-year-old ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patient who suffered an acute UGIB caused by MWS shortly after a primary coronary intervention (PCI).

A 57-year-old male patient was admitted to China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, Jilin, China) for acute persistent chest pain for 5 h after drinking.

The patient’s symptoms started 5 h ago when he was drinking, and only alleviated a little when he was referred to the hospital.

His past medical history, including a coronary artery bypass grafting history, described a vein graft to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) 3 years ago. The patient had no history of hypertension, diabetes, alcohol abuse, liver cirrhosis, or gastrointestinal diseases, but had a 25-pack-year smoking history.

The patient had no family cardiovascular diseases.

Physical examination showed bradycardia (heart rate: 50 bpm) and hypotension (blood pressure: 90/60 mmHg) but no other abnormalities.

Laboratory assessments showed a normal red blood cell (RBC) count, normal hemoglobin level (133 g/L), and normal coagulation test results. Cardiac biomarkers were significantly increased (TnI 2.40 ng/mL, myoglobin 300 mg/L, and CK-MB 32.6 U/L).

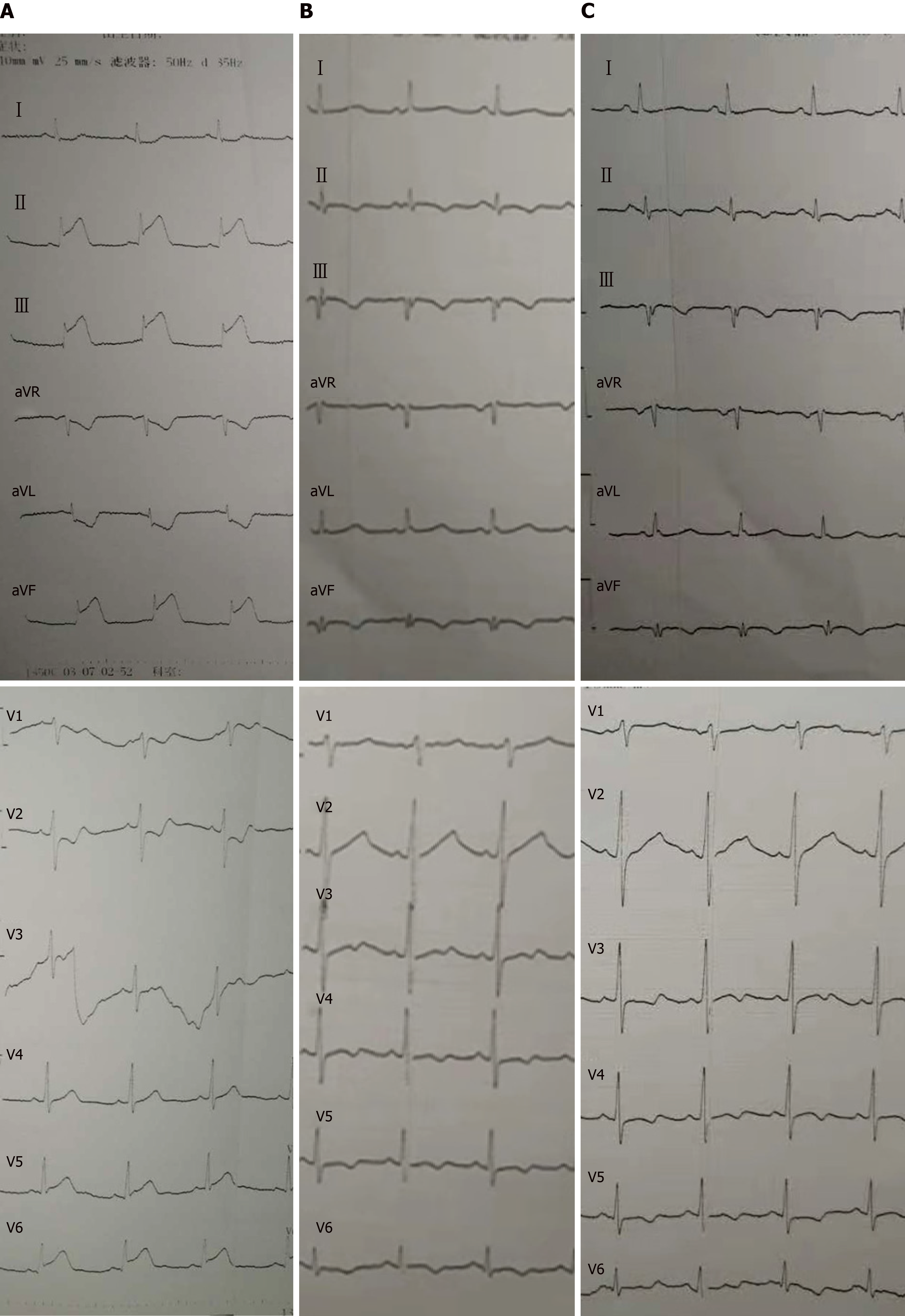

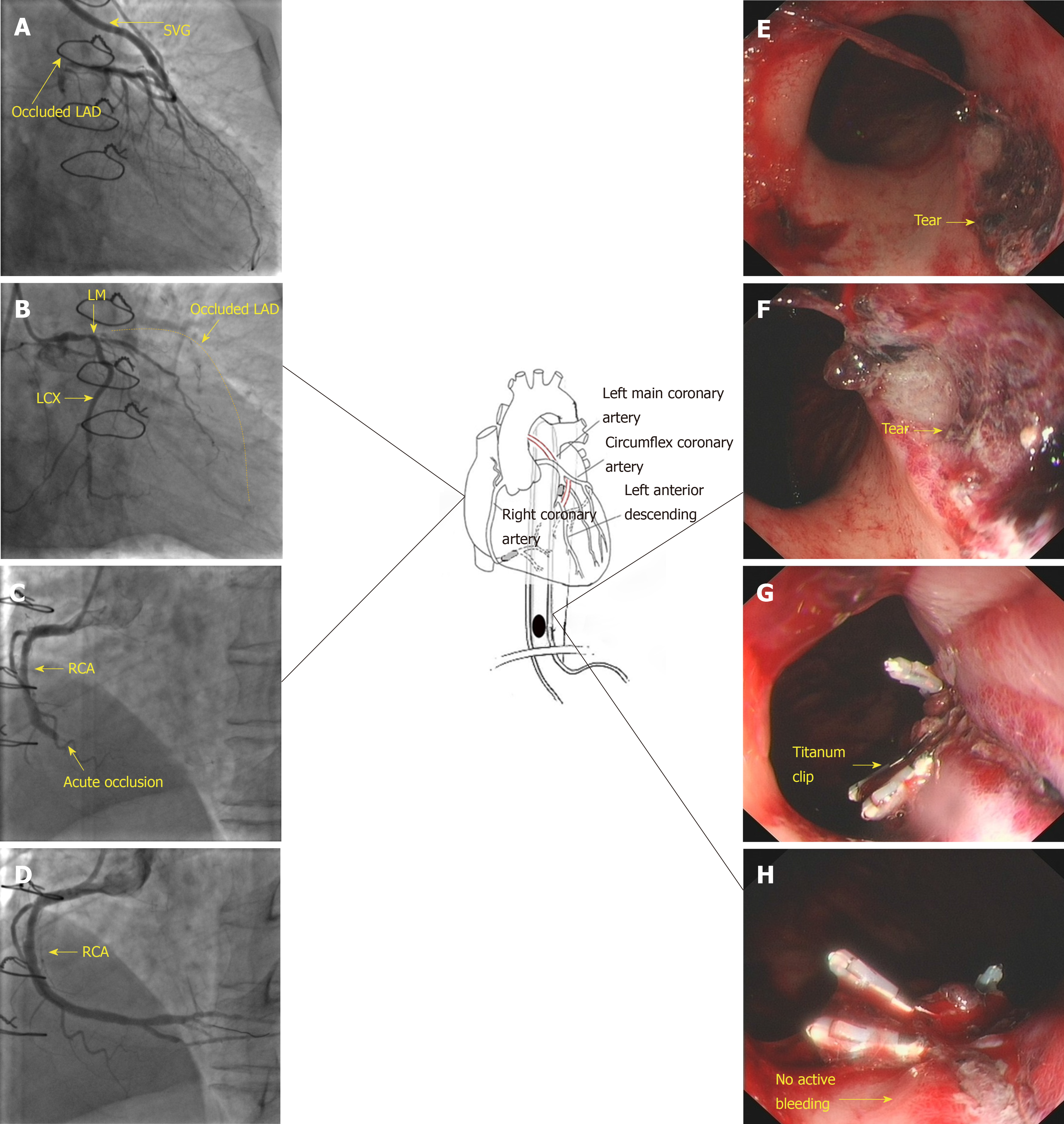

Electrocardiography (ECG) showed ST elevations in the inferior wall leads (Figure 1A). Emergency coronary angiography (CAG) showed a distal right coronary artery (RCA) occlusion and a thrombus (TIMI thrombus grade 5) (Figure 2C). There was a 40%-50% [quantitative coronary analysis (QCA)] moderate stenosis of the distal left main artery. Native LAD was occluded, and there was a 90% (QCA) severe stenosis in the distal circumflex artery (Figure 2B). The saphenous vein graft to LAD was normal (Figure 2A). After intervention, chest pain was relieved, and ECG (Figure 1B) showed that the elevated ST segment returned to normal but with a T wave inversion.

The patient experienced nausea and vomiting and subxiphoid chest pain 6 h after the procedure. The vomitus originally included the stomach contents without blood. ECG was rechecked to rule out acute thrombus formation, but no obvious changes were observed (Figure 1C). Twenty minutes later, the patient vomited again, and this time the vomitus was bloody (approximately 400 mL). Although optimal medical treatment was given, no obvious improvement was seen. An esopha-gogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed 7 hours after the PCI. A 2.0 cm, actively bleeding mucosal tear was found in the cardia. No ulcer in the stomach or duodenum and no esophageal varices or mucosal erosion was observed (Figure 2E, 2F).

According to the symptoms, ECG findings, cardiac biomarkers, CAG findings, EGD findings, and the whole course of the disease, the patient was diagnosed with acute inferior wall STEMI, MWS, and acute UGIB.

After emergency CAG, primary percutaneous coronary intervention was performed. The RCA was recanalized after thrombus aspiration, and a 3.5 mm × 33 mm drug eluting stent (Firebird2, Microport, China) was implanted in the distal RCA (Figure 2D).

The patient was first given antiemetics (metoclopramide, 10 mg, i.m.) when he had the symptoms of vomit and nausea, but the symptoms were not relieved.

After the patient had bloody vomitus, all antithrombotic drugs were stopped and food and water were strictly restricted. A proton pump inhibitor (PPI, pantoprazole, 40 mg, i.v.) and somatostatin (250 mg, q8h, i.v.) were intravenously administered. The patient vomited again 15 min later, and this time, the vomitus contained 300 mL of blood. Three units of RBC suspension was immediately perfused.

At the same time, an early endoscopic examination with close monitoring of the hemodynamic status was recommended. After the diagnosis of MWS by EGD, hemoclip treatment with seven small titanium clips [endoclips (HX610090L), OLYMPUS, JP] was performed, and the bleeding was stopped (Figure 2G and 2H). The wound was repeatedly washed, and no active bleeding was observed.

After the treatment, the chest pain was relieved and no further hematemesis occurred. Blood pressure returned to normal. To prevent stent thrombosis, dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d) was restarted.

Ten days later, the patient was discharged from the hospital. Laboratory assessments showed a normal RBC count and hemoglobin level.

We describe the process of diagnosis and salvage treatment for a case of MWS-induced acute UGIB after an AMI intervention. When there is acute UGIB after an AMI, the in-hospital and long-term mortality of the patient can substantially increase to 25.9% and 34.1%, respectively[1]. Hematemesis can cause a management dilemma for clinicians who need to balance the discontinuation of antithrombotic drugs to prevent bleeding and possible acute thrombosis of the stent.

UGIB after AMI or primary PCI is usually caused by stress[7]. MWS, also called cardial mucosal tear syndrome, is characterized by massive hematemesis, severe vomiting, and longitudinal tears of the esophagogastric junction. MWS is not a common cause of UGIB after AMI. As this case showed, hematemesis often starts with severe vomiting and massive bright red blood loss. When no improvement is seen after routine inhibition of gastric acid secretion and other drugs, early EGD can help provide a clear diagnosis indicating that MWS caused UGIB.

Although the mechanism is not fully understood, it is generally believed that the stomach contents enter the esophagus due to vomiting and the diaphragm contraction causes the pressure in the distal esophagus to instantly increase, leading to a mucosal tear of the cardia[8].

MWS-caused acute UGIB is high risk because massive blood loss induces hemodynamic instability. When MWS occurs after an AMI, it results in further hemodynamic instability and has potential for life-threating ventricular arrhythmias. Besides, intensified antithrombotic treatment of dual antiplatelet combined with anticoagulation drugs was commonly adopted in AMI post-PCI management, which definitely would increase the difficulty of disease differential diagnosis and hemostasis treatment. The key management of MWS and AMI patients is an early endoscopic examination and hemoclip treatment[8]. This process requires close collaboration between cardiologists and endoscopy experts.

No consensus has been reached regarding liberal or restrictive transfusion therapy for acute coronary syndrome with acute blood loss, although in current clinical settings, patients whose Hb < 8 g/dL with ischemic symptoms or Hb < 7 g/dL without symptoms would be recommend to receive packed RBC transfusion[9]. The on-going large clinical trial (MINT trial)[10] can possibly answer this question. The transfusion in this case was based on the fact that there was acute large-volume blood loss and it was not known whether there would be further bleeding.

Post-endoscopy management should include the prevention of recurrent bleeding. As recommended by the guidelines[11,12], administration of a prophylactic PPI is protective for most UGIB, including MWS after a coronary intervention, with dual antiplatelet therapy[13]. Dual antiplatelet therapy can be continued with the assurance of no active bleeding under endoscopy.

AMI patients often have gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting (55%)[14], early in the event, and nausea or vomiting can be the predisposing factor for MWS. Therefore, in patients with AMI combined with UGIB, clinicians should be vigilant for the possibility of MWS. In terms of treatment, in addition to the optimal medication, it is necessary to perform an early EGD to determine the cause of bleeding and, if necessary, stop bleeding with hemoclip therapy and other necessary interventions.

MWS can lead to severe UGIB after AMI and is associated with accompanying symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting. An early EGD should be performed on such patients to distinguish between stress-induced and antithrombotic drug-induced bleeding and to determine what treatment is needed to stop the bleeding.

| 1. | Chen YL, Chang CL, Chen HC, Sun CK, Yeh KH, Tsai TH, Chen CJ, Chen SM, Yang CH, Hang CL, Wu CJ, Yip HK. Major adverse upper gastrointestinal events in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention and dual antiplatelet therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1704-1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | He L, Zhang J, Zhang S. Risk factors of in-hospital mortality among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and acute myocardial infarction. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shalev A, Zahger D, Novack V, Etzion O, Shimony A, Gilutz H, Cafri C, Ilia R, Fich A. Incidence, predictors and outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kyaw MH, Lau JYW. High Rate of Mortality More Than 30 Days After Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1858-1859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wilcox CM, Cryer BL, Henk HJ, Zarotsky V, Zlateva G. Mortality associated with gastrointestinal bleeding events: Comparing short-term clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized for upper GI bleeding and acute myocardial infarction in a US managed care setting. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2009;2:21-30. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Ocazionez D, Moncada R, Gimenez CR. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus: a pictorial essay. Emerg Radiol. 2008;15:13-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Buendgens L, Koch A, Tacke F. Prevention of stress-related ulcer bleeding at the intensive care unit: Risks and benefits of stress ulcer prophylaxis. World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Rich K. Overview of Mallory-Weiss syndrome. J Vasc Nurs. 2018;36:91-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, Chaitman B, Kelsey SF, Triulzi DJ, Srinivas V, Menegus MA, Marroquin OC, Rao SV, Noveck H, Passano E, Hardison RM, Smitherman T, Vagaonescu T, Wimmer NJ, Williams DO. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165:964-971.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carson JL. Myocardial Ischemia and Transfusion (MINT) [accessed 2016 Dec 5]. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Identifier: NCT02981407. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT02981407 ClinicalTrials.gov. |

| 11. | Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, Jüni P, Kastrati A, Kolh P, Mauri L, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Petricevic M, Roffi M, Steg PG, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Levine GN; ESC Scientific Document Group; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); ESC National Cardiac Societies. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2299] [Cited by in RCA: 2143] [Article Influence: 267.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4045] [Cited by in RCA: 4463] [Article Influence: 405.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 13. | Sehested TSG, Carlson N, Hansen PW, Gerds TA, Charlot MG, Torp-Pedersen C, Køber L, Gislason GH, Hlatky MA, Fosbøl EL. Reduced risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1963-1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herlihy T, McIvor ME, Cummings CC, Siu CO, Alikahn M. Nausea and vomiting during acute myocardial infarction and its relation to infarct size and location. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:20-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Dai X, Erkut B, Kharlamov AN, Nurzynska D S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu MY