Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3353

Peer-review started: July 22, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: September 3, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 98 Days and 16.9 Hours

Congenital short bowel syndrome (SBS) associated with malrotation, gut volvulus and jejuno-ileal atresia is a very rare condition. It is a severe challenge for surgeons to preserve residual ischemic bowel segment in the management of short bowel syndrome,especially in neonates.

We report a newborn baby with gut malrotation associated with jejuno-ileal atresia, congenital SBS and jejunal volvulus. Hematemesis and abdominal distention were noted. At laparotomy, malrotation associated with jejuno-ileal atresia, congenital SBS and jenunal volvulus was confirmed. The total length of the small bowel was 63 cm with proximal jejunal bowel segment measuring 38 cm, including 18 cm necrotic segment below the Treitz’s ligament and 20 cm severe ischemic segment. The distal part of the small bowel was 25 cm in length and only about 0.8 cm in diameter. Ladd’s procedure, necrotic segment resection and end-to-back duodeno-ileal anastomosis were performed. The residual severe ischemic jejunum was preserved with single proximal stoma and distal end closure. Three months later, to restore the continuity of the isolated gut segment, end-to-end duodeno-jejunal and jejuno-ileal anastomosis was performed. The entire functional small bowel length increased to 80 cm. Intravenous fluid therapy and parenteral nutrition were discontinued on the 10th day postoperatively. Twelve months later, her body weight was 9.5 kg.

Isolation of severe ischemic bowel segment and staged anastomosis to restore the gut continuity for infants with SBS are safe and feasible.

Core tip: Congenital short bowel syndrome (SBS) associated with malrotation, gut volvulus and jejuno-ileal atresia is a very rare condition. A newborn baby with gut malrotation associated with jejuno-ileal atresia, congenital short bowel syndrome, and jejunal volvulus. Ladd’s procedure, necrotic segment resection, end-to-back duodeno-ileal anastomosis were performed. Isolation of severe ischemic bowel segment and staged anastomosis to restore the gut continuity for infant with SBS are safe and feasible.

- Citation: Geng L, Zhou L, Ding GJ, Xu XL, Wu YM, Liu JJ, Fu TL. Alternative technique to save ischemic bowel segment in management of neonatal short bowel syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(20): 3353-3357

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i20/3353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3353

Massive resection of bowel segment with severe ischemia and doubtful necrosis usually leads to short bowel syndrome (SBS)[1]. Patients with SBS have a high risk of being permanently dependent on parenteral nutrition, late severe complications and poor life quality[2]. Therefore, extensive small bowel ischemia and necrosis always present a severe challenge for surgeons. The need for and extent of resection necessary during laparotomy are difficult to determine[3]. In order to avoid SBS, many techniques have been performed. Several methods directed at increasing absorption by prolonging transit time through the residual small intestine, like vagotomy and pyloroplasty[4] and recirculating small bowel loops[5] have been used. There are reports of methods for increasing the absorptive mucosal surface area by stimulating the development of jejunal neomucosa[6]. Some studies have been designed to increase the length of the residual small bowel[7]. Palmieri et al[8] introduced a three-staged method for ischemic bowel management, which provided an approach to maximally preserve the bowel with reversible high-grade ischemic changes instead of extensive resection of severe ischemic bowel segment. Here we describe an alternative two-staged approach to save severe ischemic bowel segment in a newborn baby with malrotation associated with jejunal volvulus, jejuno-ileal atresia and congenital SBS.

A female neonate at 5 h after birth with multiple episodes of vomiting.

A female neonate of 38 wk gestation, weighing 2.95 kg and born by cesarean delivery. She was transferred to our hospital at 5 h after birth with multiple episodes of hematemesis and abdominal distention.

Gross distention and visible bowel loops in upper abdomen, without tenderness, rigidity or visible peristalsis were observed. No bowel sounds were heard, and no mass or organomegaly was palpated. No meconium passed after enema with warm normal saline. No abnormalities were found in other organ systems.

Peripheral white blood cell count and serum C-reactive protein level increased.

Abdominal plain X-ray film showed a few air-fluid levels in the left upper abdomen. Ultrasound of the abdomen revealed a dilated small bowel measuring 3.4 cm in the maximum diameter.

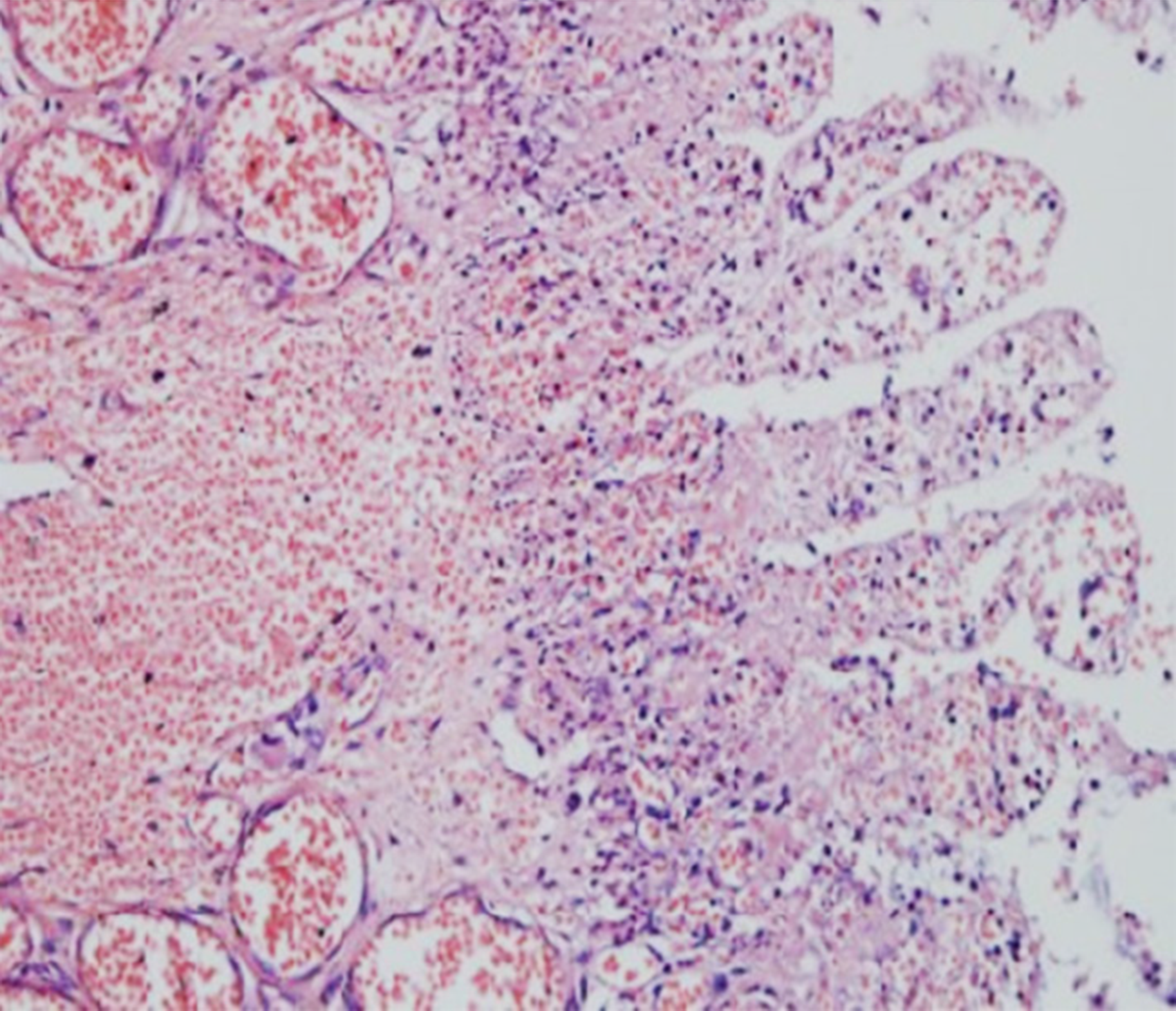

After informed consent was obtained from her guardians, the newborn baby underwent a laparotomy and diagnosed with intestinal atresia and volvulus. There were 100 mL turbid dark-green ascites in the abdominal cavity, indicating the existence of meconium peritonitis. Ladd’s band was noted in the second part of duodenum. The cecum located beneath the liver and terminal ileum was not fixed. A 360 degree clockwise jejunum volvulus was observed. Type IIIa jejuno-ileal atresia with V-shaped mesenteric defect was identified. The total length of the small bowel was 63 cm with the proximal jejunal bowel segment measuring 38 cm in length and 2.0-3.5 cm in diameter, including 18 cm necrotic segment just below the Treitz’s ligament and 20 cm severe ischemic segment with perforation at the proximal end of the atresia. The distal part of the small bowel was 25 cm in length and 0.8 cm in diameter. The ileocecal valve was intact. The diagnosis of gut malrotation associated with jejuno-ileal atresia, congenital SBS and jenunal volvulus and segmental bowel necrosis (Figure 1) was made.

Ladd’s procedure was performed. The proximal necrotic jejunal segment (18 cm in length) was excised. A single-layer end-to-back duodeno-ileal anastomosis was done. The residual severe ischemic jejunum was preserved with single proximal stoma and distal end closure. The total functional small bowel was 25 cm in length with intact ileal-cecal valve.

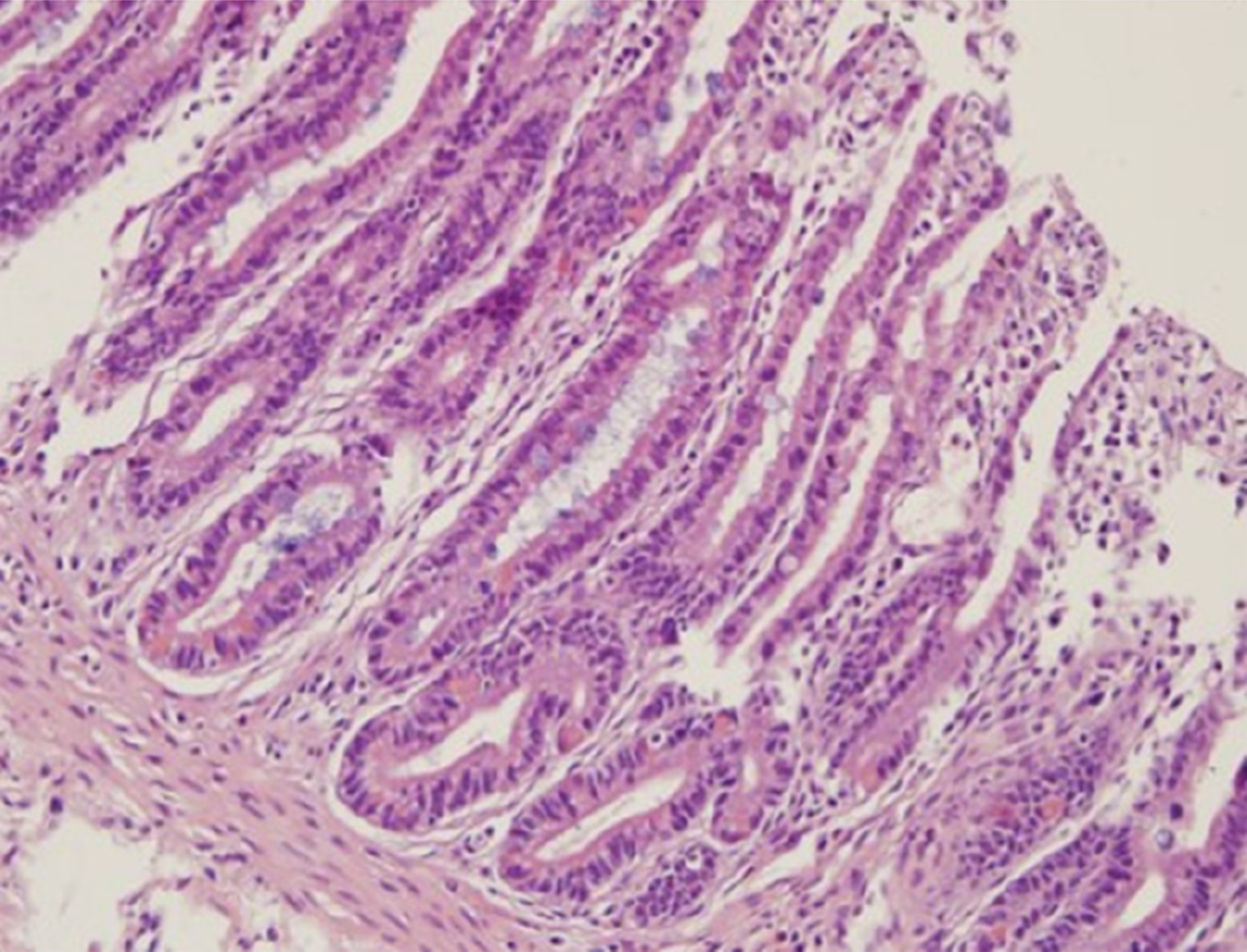

Postoperatively, intermittent parenteral nutrition combined with enteral feeding (including breastfeeding) was applied. The stoma gradually became normal 1 wk later following severe ischemia and edema. To improve the isolated gut adaptation, normal saline and hydrolyzed protein formula were infused through the stoma 1 mo later. Her body weight decreased from 2.95 kg at birth to 2.2 kg at 3 mo of age. After 1-wk parenteral nutrition through central venous catheter and breastfeeding, a second procedure was planned to restore the gut continuity of the isolated jejunal segment. Intraoperative findings showed that ileum adaption was achieved and measured 48 cm in length (vs 25 cm at birth) and 2 cm in diameter (vs 0.8 cm at birth). The isolated segment also became adapted and measured 32 cm in length and 1.5-2 cm in diameter with normal color and peristalsis. Following the primary anastomosis, end-to-end duodeno-jejunal and jejuno-ileal anastomosis was performed using two-layer sutures to restore the continuity of the bowel. The bowel mucosal structure from the site of the ileal stoma was observed (Figure 2).

After the gut continuity of the isolated segment was restored, the entire functional small bowel length became 80 cm. Intravenous fluid therapy and parenteral nutrition were discontinued on the 10th day postoperatively. She tolerated total enteral nutrition well and was discharged from hospital on postoperative day 13 without complications. Twelve months later, her body weight increased to 9.5 kg (25th percentile for her age).

Congenital SBS is a rare gastrointestinal disorder. The management of congenital SBS has improved in recent decades due to refinement in operative technique[9] and postoperative nutrition therapy[10]. The surgical management of congenital SBS is individualized and mainly involves autologous gastrointestinal reconstruction including tapering enteroplasty[11], Bianchi’s longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring[12] and serial transverse enteroplasty[13]. Intestinal transplantation is the last resort for cure[14].

Bowel with clearly irreversible full-thickness injury or no evidence of peristalsis or blood flow at “second look” operations needs to be resected. However, persistent ischemia or perforation of involved bowel may require further resection in the early postoperative period. The judgment and experience of the surgeons play a vital role in determining which bowel segment should be preserved or resected. Whatever surgical approach is used in the management of SBS to preserve as much bowel as possible is an important factor to prevent and treat SBS[15]. In our experience, by establishing isolation segment, the viability of the bowel segment can be monitored through the stoma instead of a “second look” surgery. If this segment became necrotic, resection of the bowel is easier to perform through the stoma. Moreover, single proximal stoma might be superior to two-end stomas for three reasons: (1) Bowel segment dilatation and elongation may occur due to fluid retention in the lumen; (2) One incision is easier to take care and has a cosmetic result; and (3) It is helpful to implement tube feeding.

We successfully managed this difficult case by an alternative technique. The proximal necrotic bowel segment was resected, and the severe ischemic jejunum (20 cm in length) was preserved by isolation with proximal single stoma. Moreover, we used enteral feeding to enhance the adaptation of the isolated jejunal segment. Meticulous administration of fluid, electrolyte and nutrition is the mainstay of treatment for such patients[16]. In the preoperative period of the second stage procedure, the baby received parenteral nutrition through a central venous catheter. Initiation of oral feeding was given 2 d after surgery. The intestinal function recovered, and the baby totally tolerated enteral nutrition and weaned off parenteral nutrition sooner than expected. She is well with short-term parenteral nutrition, total enteral feeding, and breastfeeding. In the 1-year follow-up period, the baby was thriving on a regular diet with normal growth and development.

Bowel isolation technique was successfully used to save severe ischemic bowel segment in this case. Enteral nutrition improved the adaptation of the isolated bowel segment. However, time to restore the continuity of the isolated bowel needs to be investigated.

| 1. | Marino IR, Lauro A. Surgeon's perspective on short bowel syndrome: Where are we? World J Transplant. 2018;8:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chandra R, Kesavan A. Current treatment paradigms in pediatric short bowel syndrome. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Duro D, Kamin D, Duggan C. Overview of pediatric short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47 Suppl 1:S33-S36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Safioleas M, Stamatakos M, Safioleas P, Diab A, Karanikola E, Safioleas C. Short bowel syndrome: amelioration of diarrhea after vagotomy and pyloroplasty for peptic hemorrhage. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;214:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Selzner M, Isenberg J, Keller HW. Current status of surgical treatment of short bowel syndrome. Zentralbl Chir. 1996;121:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mackby MJ, Richards V, Gilfillan RS, Floridia R. Methods of increasing the efficiency of residual small bowel segments: A preliminary study. Am J Surg. 1965;109:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bianchi A. Intestinal loop lengthening--a technique for increasing small intestinal length. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:145-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Palmieri T, Kimura K, Soper RT, Mitros FA. A staged surgical approach to save ischemic bowel. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:861-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Höllwarth ME. Surgical strategies in short bowel syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017;33:413-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Modi BP, Langer M, Ching YA, Valim C, Waterford SD, Iglesias J, Duro D, Lo C, Jaksic T, Duggan C. Improved survival in a multidisciplinary short bowel syndrome program. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:20-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hukkinen M, Kivisaari R, Koivusalo A, Pakarinen MP. Risk factors and outcomes of tapering surgery for small intestinal dilatation in pediatric short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1121-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hosie S, Loff S, Wirth H, Rapp HJ, von Buch C, Waag KL. Experience of 49 longitudinal intestinal lengthening procedures for short bowel syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barrett M, Demehri FR, Ives GC, Schaedig K, Arnold MA, Teitelbaum DH. Taking a STEP back: Assessing the outcomes of multiple STEP procedures. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DiBaise JK. Short bowel syndrome and small bowel transplantation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:128-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thomson AB, Chopra A, Clandinin MT, Freeman H. Recent advances in small bowel diseases: Part II. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3353-3374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Duggan CP, Jaksic T. Pediatric Intestinal Failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:666-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Akarsu M, Sikiric P S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Qi LL