Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3322

Peer-review started: May 5, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: September 22, 2019

Accepted: September 25, 2019

Article in press: September 25, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 174 Days and 14.3 Hours

Polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) injections were once common in breast augmentation and have been prohibited for augmentation mammaplasty in China since a large number of patients who underwent breast augmentation with PAAG injections have continued to seek medical advice as a result of related complications. Among all these complications, distant migration is relatively rare.

A 49-year-old female presented at the hospital with a one-year history of a vulvar lump. The sonography of the lump showed several subcutaneous fluid-filled regions from the left vulva to the pubic symphysis, which suggested possible fat liquefaction. An enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic area, which was considered a benign lesion. Intraoperative observations showed that the mass did not have an obvious capsule, the subcutaneous tissue presented as a cavity, and some yellow material came out of this cavity. A culture of the drainage did not show bacterial contamination. Histopathology revealed a foreign body granuloma. After resection and closed drainage, lumps were successively observed in the left lower abdomen and the bilateral hypochondriac region with infections. Sonography found that the hypoechoic areas in the bilateral hypochondriac region seemed continuous with deep in the breasts. The patient reported that she had undergone surgery with PAAG injections 20 years ago after she was repeatedly asked about her past history. Finally, a diagnosis of distant migration of PAAG was made.

PAAG gel can migrate after long periods of time. A diagnosis should not be limited to the area where the symptom develops.

Core tip: Among the complications of PAAG injections, distant migration is relatively rare. Symptoms at presentation depend on the course and sometimes may be misdiagnosed. Here, we present a rare case of a patient who repeatedly presented with lumps and infections, without bacterial contamination or an obvious histopathologic explanation. This case shows that PAAG gel can migrate after long periods of time, and debridement surgery may be necessary even without symptoms. It took four months to make an accurate diagnosis since the patient did not disclose her history, which serves as a reminder not to limit our diagnostic ideas to the symptomatic area.

- Citation: Zhang MX, Li SY, Xu LL, Zhao BW, Cai XY, Wang GL. Repeated lumps and infections: A case report on breast augmentation complications. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(20): 3322-3328

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i20/3322.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3322

Polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) injections were once prevalent in breast augmentation and have been prohibited for augmentation mammaplasty in China since a large number of patients whose breasts were augmented with PAAG injections have continued to seek medical advice as a result of related complications. Reports of unfavorable results causing debridement operations are rare; however, with an increasing number of complications, PAAG injections have been shown to be potentially dangerous, causing substantial irreversible damage to the breasts of previously healthy women[1,2]. The exact number of patients who underwent PAAG injections in breast augmentation remains unclear, but approximately 300000 women are estimated to have undergone this procedure[3].

The reported complications[4] following PAAG injections for augmentation mammaplasty include swelling, pain, subcutaneous nodules, infection and gel migration. Among all these complications, local migration is common and can be easily diagnosed. However, distant migration is relatively rare. The symptoms at presentation depend on the course, and these symptoms may sometimes be misdiagnosed. Here we present a rare case of a patient who repeatedly presented lumps and infection, without bacterial contamination and obvious histopathologic explanations. The aim of this case report is to highlight this unusual complication to avoid incorrect diagnosis and to provide more insights for clinical diagnosis.

A 49-year-old female presented at the hospital with a one-year history of a vulvar lump with swelling and was admitted to the general surgical department.

The patient found a vulvar lump a year ago with swelling and tenderness, which had recently gradually increased.

There was a past history of cervical conization 8 years ago. There was no history of diabetes or hypertension and no family history.

On physical examination, the lump was tender and was as large as a finger. The patient’s temperature was 36.7 °C, with a pulse rate of 82 beats/min and a respiration rate of 19/min; the patient’s blood pressure was 14.1/9.6 kPa.

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg; 6.48 S/CO; reference range: < 1.00 S/CO) and hepatitis B core antibody (HbcAb, 15.52 U/L, reference range < 10.00 U/L) results were positive. Blood analysis, biochemical tests, coagulation function, renal function, tumor markers, syphilis, HIV tests, and other tests showed no obvious abnormalities.

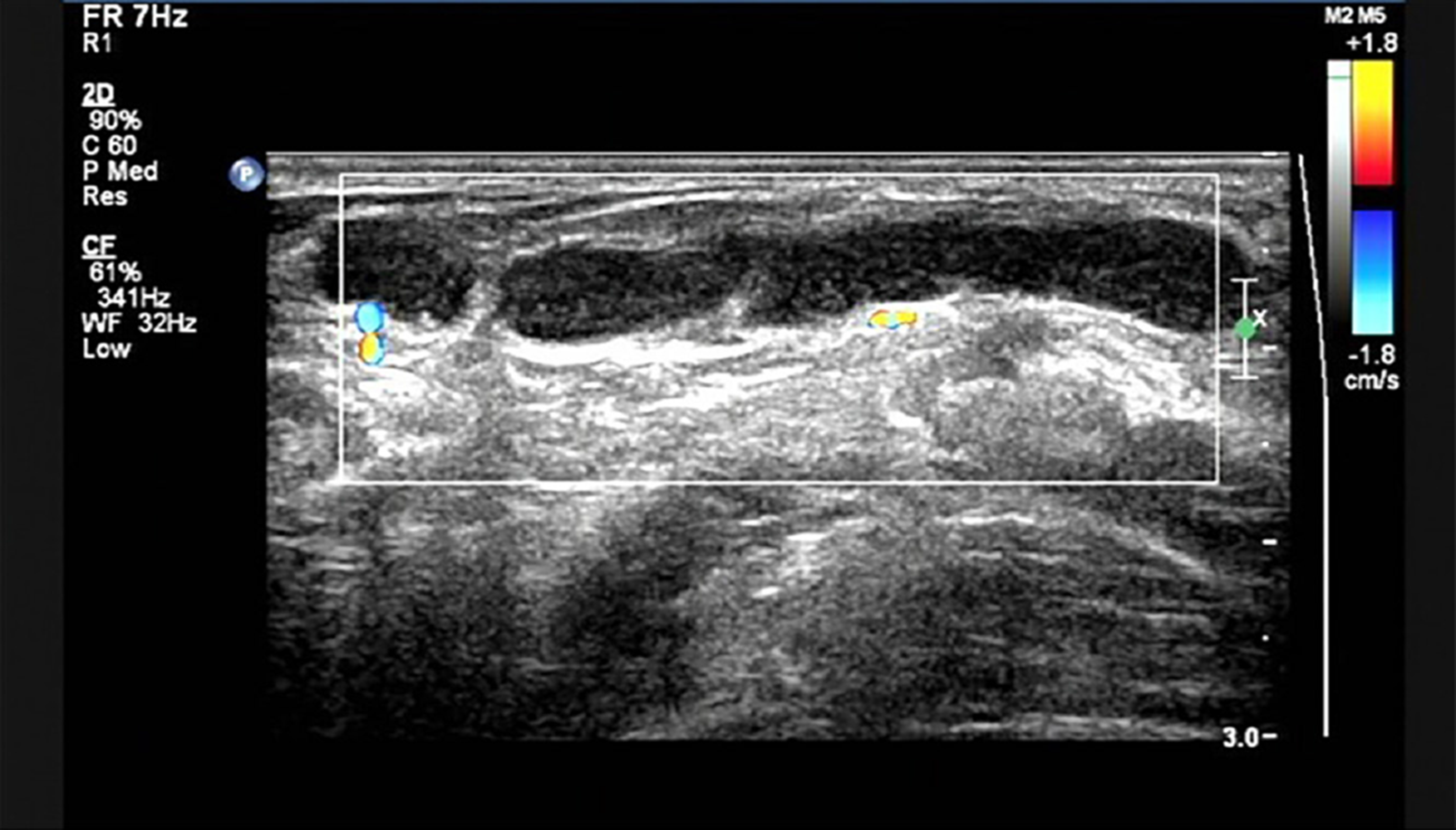

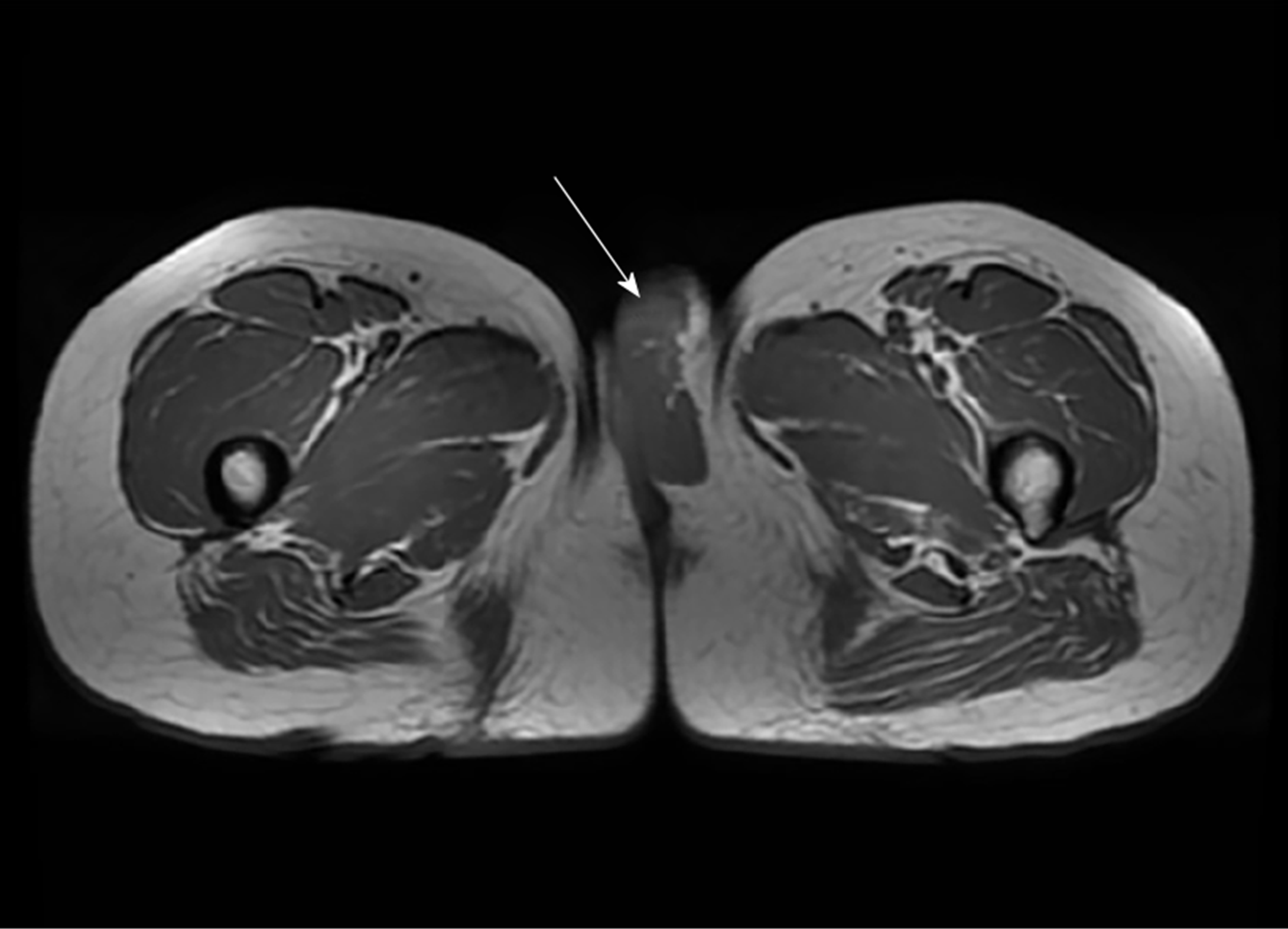

An initial imaging evaluation by sonography (Figure 1) showed several subcutaneous fluid-filled regions from the left vulva to the pubic symphysis that were multilocular and mobile. The largest lump was 6.11*1.84*2.62 cm, and all of these fluid-filled regions were considered possible fat liquefaction. The lump was further evaluated by a pelvic cavity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This scan revealed a cystic area (Figure 2), which was considered a benign lesion, including lymphangioma.

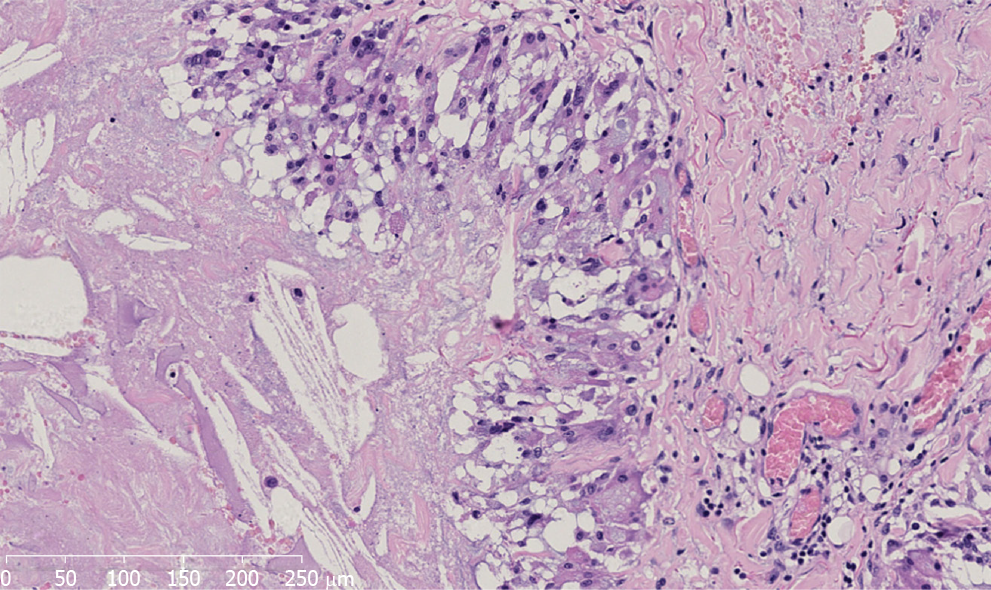

The resection of the vulvar mass and closed drainage were conducted. Intraoperative observations showed that the mass did not have an obvious capsule, and its boundaries were unclear. The subcutaneous tissue presented as a cavity, and yellow material, similar to bean dregs, came out of the cavity (Figure 3). Histopathology revealed that the tissue was composed of a foreign-body granuloma (Figure 4). She was discharged on first postoperative day. Three weeks postoperatively, the patient was hospitalized as a result of fever and chills, with a peak temperature of 38.7 °C. The wound was healing slowly, and the left lower abdominal wall was swollen, tender, and hot. A blood test showed that high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (84.6 mg/L), neutrophil granulocytes (21.8*109/L) and white blood cells (23.4*109/L) were obviously increased. Additionally, an abdominal CT scan indicated extensive infiltration and effusion from the left hypochondriac region to the vulva, mostly in the left lower abdomen, and postoperative changes were suspected (Figure 5). Subsequently, the patient underwent local drainage with an 8F "pigtail" tube. The drainage fluid seemed similar to that of the last time. The drainage culture showed no bacterial contamination. Then, the patient was discharged with decreasing effusion.

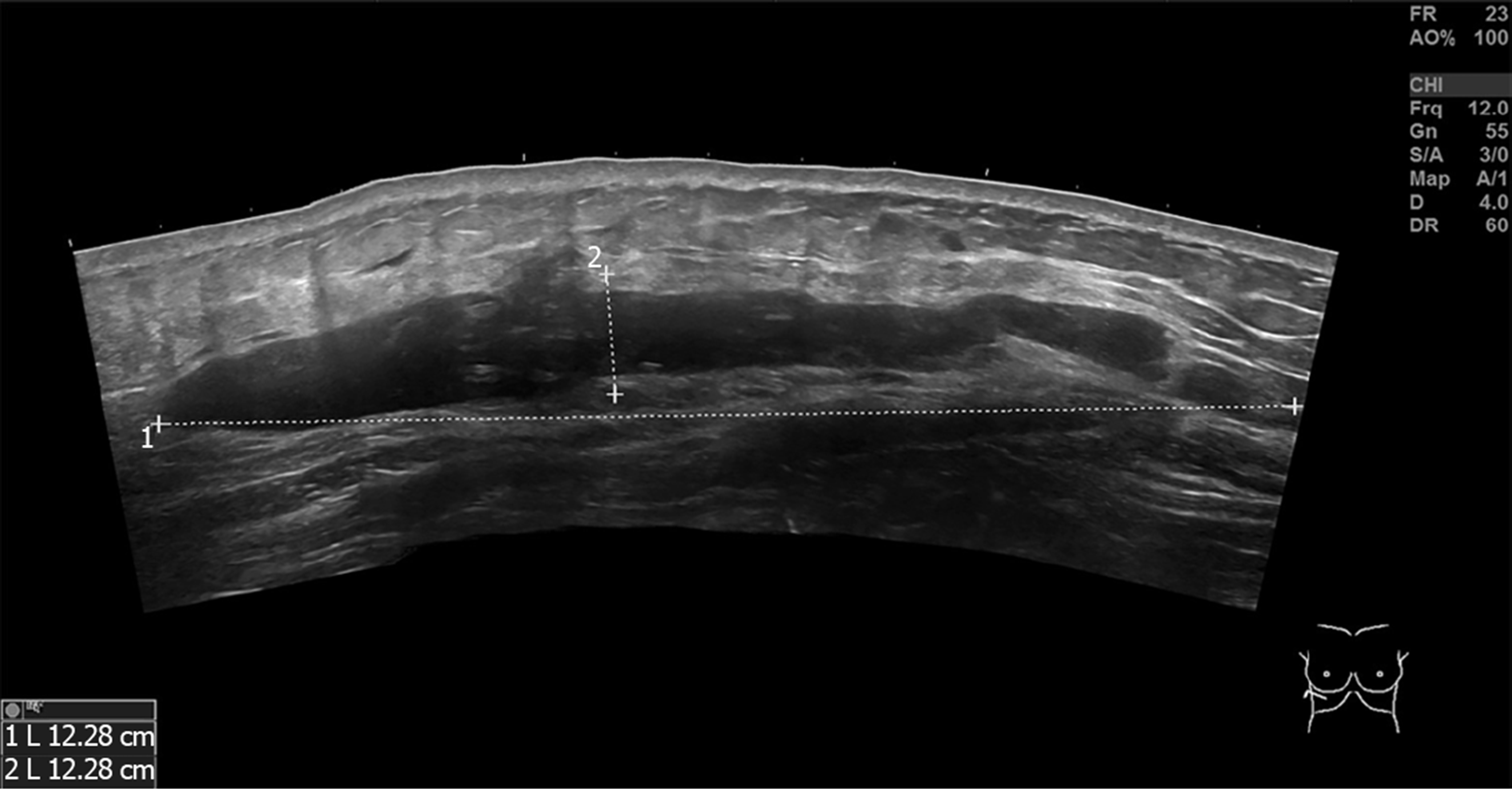

However, she was readmitted to the hospital a month later, reporting the swelling of the bilateral chest wall with fever. The highest temperature was 37.8 °C, and the blood test was similar to that at the last admission, with increased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (48.5 mg/L), neutrophil granulocytes (9.65*109/L), and white blood cells (11.6*109/L). The sonography of the bilateral hypochondriac area revealed a hypoechoic area on each side shaped like bars (Figure 6). The size of the left region was 21.95*2.32*9.59 cm, and the size of the right region was 12.28*1.30*12.01 cm. Both hypoechoic areas seemed continuous with deep in the breasts. The patient reported that she had hid the fact that she had undergone breast augmentation surgery with PAAG injections 20 years ago until she was repeatedly asked about her past history by an ultrasound doctor.

Finally, based on the history and the repeated lumps and infection, a diagnosis of distant migration of PAAG was made.

The patient refused surgery and was then treated with anti-inflammatory therapies and drainage.

After 6 months of follow-up, the patient's condition was stable.

Based on the fluidity of PAAG and the thin fibrous capsule surrounding the gel, the injected PAAG breaks down under certain conditions, including pressure, gravity, trauma, and massage, which may accelerate gel migration by disrupting the fibrous capsule.

PAAG injections are performed mostly in retromammary space, where the structure is loose. PAAG can move down the surface of the chest muscles to lower areas through the retromammary space. The distant migration in this patient appeared after a long period of time and was combined with infection after drainage. A chronic cavity formed once the PAAG reached the vulva and was maintained for prolonged periods. The drainage in this case did not resemble the drainage that is typically reported in the literature, which is thick, yellow, granular, and colloid with small transparent particles[5,6]. This may be the reason that inflammatory cells infiltrated the area and broke down the original structure.

Breast duct injury and perioperative contamination during gel injection were believed to play an essential part in infection. In this case, the vulvar mass resection exposed the wound to streams of PAAG, which we speculate may have been the reason of repeated infections. Although microorganisms can grow easily in gel solutions and can move when the gel migrates, the culture of the drainage showed no bacterial contamination in this case, and the swelling and fever may have been be due to an inflammatory reaction to the foreign body.

Some scholars[7,8] believe that patients with PAAG injections without complications do not need treatment. However, in this case, even after 20 years, the gel was still able to migrate and cause an infection; thus, treatment may need to be reconsidered. Although there are no standard therapeutic regimens, timely debridement surgery may be the most effective treatment for complications currently[4,9-11].

It is noteworthy that it took four months to accurately diagnose this patient. Female patients, especially in China, may hide their history about their sex life and breast augmentation due to embarrassment or because they do not believe that it is associated with diseases, which makes diagnosis more difficult. It is important not to limit diagnostic possibilities to the place where the symptoms are located. In this case, lumps appeared three times in different parts of the body, and it is remarkable that each lump appeared higher on the body than the previous one. The symptoms and examination results were not typical enough to make the correct diagnosis, but the regular change of location could serve as a diagnostic clue for a high lesion.

PAAG gel can migrate after extended periods of time. Timely debridement surgery may be necessary even when symptoms are not present after polyacrylamide hydrogel injection. Diagnostic possibilities should not be limited to the place where the symptom is located.

Ming-Xuan Zhang wishes to thank Wen-Qi Zhang and Huan Zhang for their support over the past decade.

| 1. | Qiao Q, Wang X, Sun J, Zhao R, Liu Z, Wang Y, Sun B, Yan Y, Qi K. Management for postoperative complications of breast augmentation by injected polyacrylamide hydrogel. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29:156-61; discussion 162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ghasemi HM, Damsgaard TE, Stolle LB, Christensen BO. Complications 15 years after breast augmentation with polyacrylamide. JPRAS Open. 2015;4:30-34. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Z, Li S, Wang L, Zhang S, Jiang Y, Chen J, Luo D. Polyacrylamide hydrogel injection for breast augmentation: another injectable failure. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CR399-CR408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luo SK, Chen GP, Sun ZS, Cheng NX. Our strategy in complication management of augmentation mammaplasty with polyacrylamide hydrogel injection in 235 patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:731-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ibrahim RM, Lauritzen E, Krammer CW. Breastfeeding difficulty after polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) mediated breast augmentation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;47:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jin R, Luo X, Wang X, Ma J, Liu F, Yang Q, Yang J, Wang X. Complications and Treatment Strategy After Breast Augmentation by Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Injection: Summary of 10-Year Clinical Experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:402-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Margolis NE, Bassiri-Tehrani B, Chhor C, Singer C, Hernandez O, Moy L. Polyacrylamide gel breast augmentation: report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 2015;39:339-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Leung KM, Yeoh GP, Chan KW. Breast pathology in complications associated with polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAAG) mammoplasty. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:137-140. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chen B, Song H. Management of Breast Deformity After Removal of Injectable Polyacrylamide Hydrogel: Retrospective Study of 200 Cases for 7 Years. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016;40:482-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zemskov VS, Zavgorodniĭ IA, Roshchina LA, Fedoruk VI, Zemskova MV, Kolomatskaia LB, Slivka VP. Endoprosthesis of mammary glands using hydrogel prosthesis PAAG “Interfall”. Klin Khir. 2000;23-24. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Unukovych D, Khrapach V, Wickman M, Liljegren A, Mishalov V, Patlazhan G, Sandelin K. Polyacrylamide gel injections for breast augmentation: management of complications in 106 patients, a multicenter study. World J Surg. 2012;36:695-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gabriel S, Santiago FR S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH