Published online Jan 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.122

Peer-review started: October 19, 2018

First decision: November 27, 2018

Revised: December 18, 2018

Accepted: January 3, 2019

Article in press: January 3, 2019

Published online: January 26, 2019

Processing time: 99 Days and 21.7 Hours

This case-control study compared the short-term clinical efficacy of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) using a prolapsing technique and the conventional laparoscopic-assisted approach for low rectal cancer.

To further explore the application value of the transanal placement of the anvil and to evaluate the short-term efficacy of NOSES for resecting specimens of low rectal cancer, as well as to provide a theoretical basis for its extensive clinical application.

From June 2015 to June 2018, 108 consecutive laparoscopic-assisted low rectal cancer resections were performed at our center. Among them, 26 specimens were resected transanally using a prolapsing technique (NOSES), and 82 specimens were resected through a conventional abdominal wall small incision (LAP). A propensity score matching method was used to select 26 pairs of matched patients, and their perioperative data were analyzed.

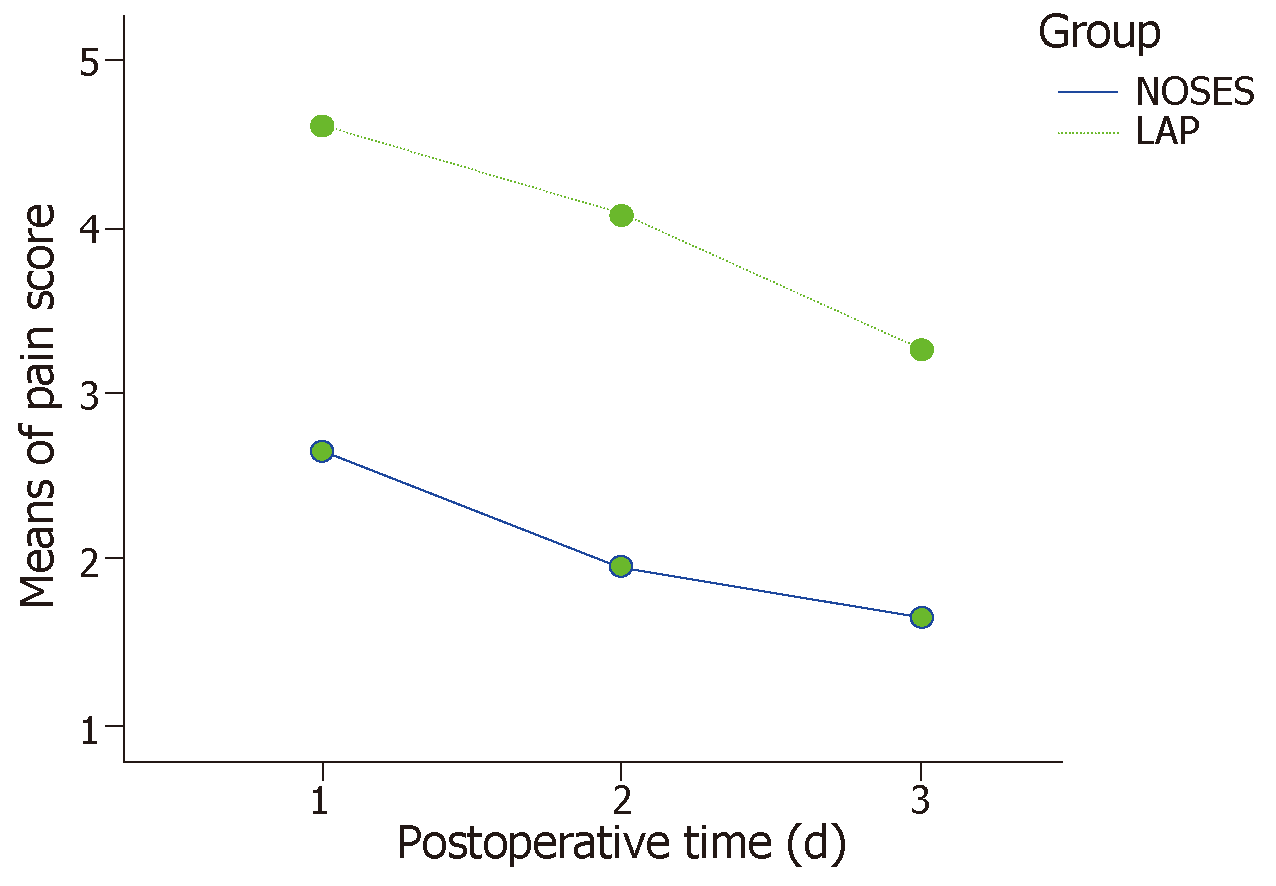

The baseline data were comparable between the two matched groups. All 52 patients underwent the surgery successfully. The operative time, blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, postoperative complication rate, circumferential margin involvement, postoperative follow-up data, and postoperative anal function were not statistically significant. The NOSES group had shorter time to gastrointestinal function recovery (2.6 ± 1.0 d vs 3.4 ± 0.9 d, P = 0.006), shorter postoperative hospital stay (7.1 ± 1.7 d vs 8.3 ± 1.1 d, P = 0.003), lower pain score (day 1: 2.7 ± 1.8 vs 4.6 ± 1.9, day 3: 2.0 ± 1.1 vs 4.1 ± 1.2, day 5: 1.7 ± 0.9 vs 3.3 ± 1.0, P < 0.001), a lower rate of additional analgesic use (11.5% vs 61.5%, P = 0.001), and a higher satisfaction rate in terms of the aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall after surgery (100% vs 23.1%, P < 0.001).

NOSES for low rectal cancer can achieve satisfactory short-term efficacy and has advantages in reducing postoperative pain, shortening the length of postoperative hospital stay, and improving patients’ satisfaction in terms of a more aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall.

Core tip: The efficacy and safety of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) for low rectal cancer using a prolapsing technique remain unclear. To reduce selection bias, a propensity score matching was introduced to achieve a comparison between the NOSES and laparoscopic groups.

- Citation: Hu JH, Li XW, Wang CY, Zhang JJ, Ge Z, Li BH, Lin XH. Short-term efficacy of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery for low rectal cancer. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(2): 122-129

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i2/122.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.122

The incidence of colorectal cancer has increased year by year and currently ranks fifth in the number of deaths from malignant tumors in China[1]. The most common types include mid and low rectal cancer[2]. Due to the recent rapid development of laparoscopic techniques and comprehensive treatment concepts, laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) has become the preferred choice for surgeons[3]. Due to its better operative field exposure, preservation of the anus with a lower positivity of the circumferential resection margin (CRM) has become possible in more patients with rectal cancer[4]. However, conventional laparoscopic TME still requires the specimen to be removed through an auxiliary incision in the abdominal wall, and thus, incision-related complications still cannot be avoided[5]. Moreover, patients may not only be concerned with the radical resection of tumor but are also beginning to pay more attention to postoperative quality of life[6]. Wang et al[7] defined the various surgical methods for avoiding an abdominal auxiliary incision as natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) and proposed ten practical manipulations of NOSES according to the location of tumor and the approach for removing the specimen. The radical resection of low rectal cancer using a prolapsing technique through the anus is one of the common forms of NOSES[8]. Based on the understanding of the anvil placement during NOSES, the anorectal surgery team of our center adopted a modified method of anvil placement to avoid abdominal infection and tumor cell dissemination during surgery and have achieved good clinical effectiveness[9]. To further explore the application value of the transanal placement of the anvil and to evaluate the short-term efficacy of NOSES for resecting specimens of low rectal cancer, as well as to provide a theoretical basis for its extensive clinical application, this study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 108 patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted low rectal cancer resection at our center from June 2015 to June 2018.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) low rectal cancer in which the margin was 4 to 6 cm proximate to the anal margin; (2) protuberant tumor with a circumferential diameter < 3 cm; (3) ulcerated tumor with less than 1/2 of the circumferential length of the rectal wall invasion; (4) no distant metastasis and preoperative examination showing a tumor stage of T1-3N0M0; and (5) no history of abdominal surgery.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2; (2) patients with sigmoid colon and mesangial hypertrophy; (3) the sigmoid colon and its mesentery were not long enough to be pulled out through the anus; (4) patients complicated with obstruction, hemorrhage, or perforation and in need of emergency surgery; (5) patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy; and (6) patients who received a preventive terminal ileostomy.

The clinical data of 108 patients who underwent the laparoscopic radical resection of low rectal cancer at the Department of Anorectal Surgery of Huaihe Hospital Affiliated to Henan University from June 2015 to June 2018 were collected. The patients were fully informed about the procedures and had the privilege of choosing their desired procedure. The 108 patients were divided into two groups: A NOSES group and a laparoscopy (LAP) group. A total of 26 patients underwent NOSES, in which an auxiliary incision was not made in the abdominal wall, the anvil was transanally placed, and the tumor was excised using a prolapsing technique. This procedure was reviewed and approved by the hospital Ethics Committee (No. 201566). A total of 82 patients in the LAP group underwent a conventional procedure in which a small incision in the abdominal wall was used to remove the specimen.

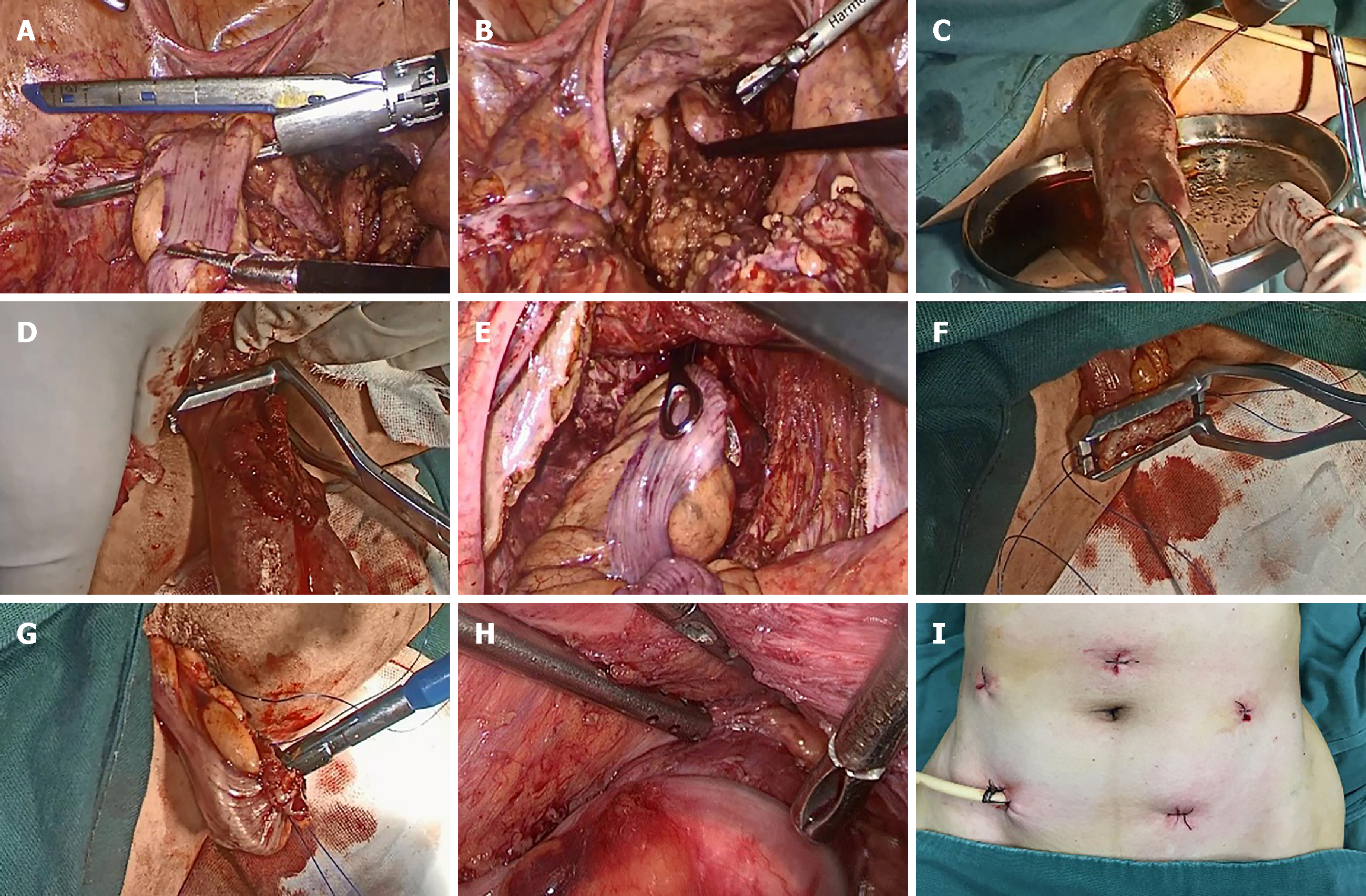

The patients in both groups underwent a routine preoperative preparation. After successful anesthesia, patients were placed in the modified lithotomy position. The pneumoperitoneum pressure was maintained at 12 mmHg. A 10-mm trocar was placed at the upper umbilical edge for introducing a laparoscope. Three 5-mm trocars were placed at the horizontal level of the umbilicus in the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle and the left lower abdomen, respectively, and served as auxiliary operation ports; a 12-mm trocar was placed into the right lower abdomen as the main operation port. The central approach was used to perform TME. The proximal sigmoid mesentery was fully dissected while protecting the peri-intestinal vascular arch. The bowel loop was skeletonized at the sites 2-3 cm distal to the lower edge of the tumor and 10 cm proximal to the tumor. The differences in the NOSES group are described below. The bowel loop was divided in the proposed site proximal to the tumor (Figure 1A); a pair of sponge forceps was inserted via the anus to grasp the distal rectum, which was then pulled and everted out of the body through the anus (Figure 1B); dilute complex iodine was used to wash the everted rectum several times (Figure 1C); a pair of purse-string forceps was used to clamp the rectum at the site 1-2 cm distal to the tumor under direct vision (Figure 1D); the rectum was divided and the specimen was removed; the sponge forceps were inserted into the abdominal cavity through the anus to pull the distal end of the sigmoid colon out of the body (Figure 1E); purse-string forceps were used to clamp the distal end of the sigmoid colon, the sigmoid wall was incised, and the blood supply to the distal end of the sigmoid colon was verified (Figure 1F); the anvil was inserted into the distal sigmoid colon and the purse-string suture was tightened (Figure 1G); the distal sigmoid colon with the anvil was returned to the abdominal cavity, and the rectal sigmoid end-to-end anastomosis was performed after tightening the purse-string suture at the rectal stump (Figure 1H); and no auxiliary incision was made in the abdominal wall (Figure 1I). A small incision was made in the abdominal wall and used to remove the specimen in the LAP group.

The intraoperative and postoperative parameters were selected as the main parameters, including the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, number of dissected lymph nodes, CRM, usage rate of postoperative analgesics, postoperative complication rate, time to postoperative gastrointestinal functional recovery, length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative follow-up (range, 3-39 mo; median 25 mo), postoperative anal function, and patient satisfaction with the postoperative abdominal wall appearance. The patients’ postoperative quality of life was evaluated. Postoperative anal function was evaluated using the low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) rating scale[10]: no LARS: 0-20; minor LARS: 21-29; and major LARS: 30-42. The visual analog scale (VAS) was assessed on days 1, 3, and 5 after surgery.

This study was a retrospective, nonrandomized controlled study with a difference in short-term efficacy that may be due to inconsistent baseline data. Therefore, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance the baseline data between the groups. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the variable assignment of the baseline data in 108 patients. The obtained P-value was the propensity score (probability of accepting the new procedure). The pair matching was 1:1 according to the least-squares matching method, and the caliper value was 0.2. SPSS version 19.0 was used for statistical analyses. The quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using an independent samples t-test. Qualitative data were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed test).

The baseline data of the 26 pairs of cases obtained by PSM were evenly distributed between the two groups (P > 0.05 for all) and were comparable (Table 1). In the NOSES group, there were four patients with postoperative urinary retention and one patient with a pulmonary infection who improved after symptomatic treatment. One patient with anastomotic stenosis improved after anal sphincter dilation treatment. In the LAP group, there were four patients with postoperative urinary retention; two patients experienced anastomotic leakage, which was cured after drainage and a nutritional regimen; and one patient with abdominal wall incision infection, one patient with early anastomotic hemorrhage, and one patient with a pulmonary infection were cured after conservative symptomatic treatment. Other intraoperative and postoperative conditions were shown in Table 2. The pain scores on days 1, 3, and 5 after surgery were significantly lower in the NOSES group than in the traditional LAP group, as shown in Figure 2.

| Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

| NOSES (n = 26) | LAP (n = 82) | P-value | NOSES (n = 26) | LAP (n = 26) | P-value | |

| Age (yr) | 63.1 ± 8.3 | 60.3 ± 6.8 | 0.251 | 63.1 ± 8.3 | 61.5 ± 7.6 | 0.480 |

| Sex | 0.345 | 0.157 | ||||

| Male | 17 (65.4) | 45 (54.9) | 17 (65.4) | 15 (57.7) | ||

| Female | 9 (34.6) | 37 (45.1) | 9 (34.6) | 11 (42.3) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 ± 4.7 | 25.8 ± 3.5 | 0.264 | 26.5 ± 4.7 | 26.4 ± 4.6 | 0.965 |

| ASA grade | 0.384 | 0.535 | ||||

| I | 8 (30.8) | 16 (19.5) | 8 (30.8) | 11 (42.3) | ||

| II | 16 (61.5) | 54 (65.9) | 16 (61.5) | 12 (46.2) | ||

| III | 2 (7.7) | 12 (14.6) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (11.5) | ||

| Distance from the lower edge of the tumor to the anal margin (cm) | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 0.812 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 0.700 |

| Preoperative CEA (ng/mL) | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 0.745 | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 0.624 |

| cTNM grade | 0.202 | 0.140 | ||||

| T1 | 4 (15.3) | 7 (8.5) | 4 (15.3) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| T2 | 14 (53.8) | 34 (41.5) | 14 (53.8) | 20 (76.9) | ||

| T3 | 8 (30.7) | 41 (50) | 8 (30.7) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| Outcome | NOSES (n = 26) | LAP (n = 26) | P-value |

| Operative time (min) | 182.1 ± 22.9 | 185.4 ± 26.6 | 0.628 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 60.8 ± 50.0 | 66.2 ± 48.4 | 0.695 |

| Number of dissected lymph nodes (pieces) | 13.8 ± 2.0 | 13.7 ± 1.4 | 0.752 |

| CRM | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 0.490 |

| Postoperative VAS | < 0.0011 | ||

| Day 1 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 4.6 ± 1.9 | |

| Day 3 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | |

| Day 5 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | |

| Usage rate of additional analgesics | 3 (11.5) | 16 (61.5) | 0.001 |

| Postoperative complication rate | 6 (23.1) | 10 (38.5) | 0.229 |

| Time to gastrointestinal function recovery (d) | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.006 |

| Length of postoperative hospital stay (d) | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.003 |

| Follow-up | 0.428 | ||

| Local recurrence | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Distant metastasis | 2 (7.7) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Death | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Postoperative anal function | 0.448 | ||

| No LARS | 3 (11.5) | 4 (15.4) | |

| Minor LARS | 20 (76.9) | 16 (61.5) | |

| Major LARS | 3 (11.5) | 6 (23.1) | |

| Postoperative satisfaction rate of abdominal wall appearance | < 0.001 | ||

| Satisfied | 26 (100) | 6 (23.1) | |

| Dissatisfied | 0 (0) | 20 (76.9) |

After decades of development, laparoscopic surgery has been proven to have the same radical effect on tumors as open surgery[3]. As the standard procedure of laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery, TME has been included in the latest guidelines for rectal cancer by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). However, in patients with low rectal cancer with pelvic stenosis and obesity, there are still some challenges regarding mobilization and dividing in laparoscopic surgery. In this situation, using NOSES for the transanal resection of a tumor reported by Alam et al[11] showed an obvious advantage. Laparoscopic TME allows the tumor to be removed under direct vision, which ensures a lower positive rate of the CRM. However, the use of Ketu arc cutting stapler still has staples. The overlap of two staples may form a risk-triangle area that is a high risk factor for anastomotic leakage in the end-to-end anastomosis between the rectum and sigmoid colon[12]. Some researchers have realized this risk and tried to use an additional layer of sutures to reduce the risk-triangle-related complications but have not seen significant effectiveness[13,14]. On this basis, Li et al[9] used a modified procedure in which the anvil was placed outside the body and the tumor was removed by means of a prolapsing technique. In their study, a purse-string suture technique was used instead of a stapler, under the premise of ensuring an infection-free and tumor-free procedure. The use of the purse-string suture technique can reduce the cost of medical treatment and eliminate the risk-triangle area formed by the overlap of staples during the anastomosis. It somewhat eliminates one of the high-risk factors of anastomotic leakage.

In addition, more attention must be paid to the quality of life after surgery and the aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall in the current environment. The exploration of completely endoscopic surgery through the natural cavity has never ceased. The utilization of complete transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) is a pilot attempt[15], but its safety and clinical application value lack the support of evidence-based medicine[16-18]. Moreover, due to limitations in instruments and surgical skills, TaTME can be performed with the need of a laparoscopic abdominal assisted operation in most cases. However, it is undeniable that TaTME is becoming a new trend around the world[19]. In this study, the PSM method was used to effectively reduce the confounding bias of the baseline data. After data matching, the data mimics being managed in a randomized study. The operative time, intraoperative blood loss, number of dissected lymph nodes, postoperative anal function, and postoperative follow-up were not statistically significant between the NOSES group and LAP group, each of which included only 26 matched cases (Table 1). Compared with the conventional specimen removal via a small incision in the LAP group, only a 5- or 12-mm-long incision scar (incision for the trocar) was noted in the abdominal wall after NOSES, and the patients were more satisfied with the aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall. NOSES was also associated with a lower postoperative pain score (Figure 2), lower usage of additional analgesics, and an effective reduction in postoperative pain. Moreover, the reduction in postoperative pain was shown to eliminate the limitation of early postoperative activities and benefit the recovery of postoperative gastrointestinal function (Table 2). Quick rehabilitation can reduce the complications associated with prolonged bed rest.

The emergence of a new surgical procedure is always accompanied by doubts. In terms of the anvil placement outside the body, tumor resection using a prolapsing technique, and NOSES, many researchers have questioned how to ensure blood supply to the distal sigmoid colon after it is pulled out of the body through the anus and how to reduce the tension of the anastomotic site. Since 2015, the authors have carried out 32 cases of this procedure. In only one case, the sigmoid colon was not long enough to be pulled out of the body; after mobilizing the splenic flexure of the colon, the distal sigmoid colon was able to be pulled out for the anvil placement. Figure 1F showed evidence of a sufficient blood supply to the distal sigmoid colon. Of course, the indications for the anvil placement outside the body, tumor resection using a prolapsing technique, and NOSES should be strictly controlled in order to continuously improve this procedure in an environment with doubt about the procedure.

In summary, tumor resection using a prolapsing technique, and laparoscopic radical resection of low rectal cancer without an auxiliary incision is one of the approaches of NOSES, and it has advantages in reducing postoperative pain, accelerating recovery, lowering medical costs, and improving the postoperative aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall. However, prospective randomized controlled trials with a large sample size are needed to verify the long-term tumor-free survival and overall survival.

The purpose of modern surgery is functional and minimally invasive. More attention must be paid to the quality of life after surgery and the aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall in the current environment. The exploration of completely endoscopic surgery through the natural cavity has never ceased.

This case-control study compared the short-term clinical efficacy of natural orifice specimen extraction surgery (NOSES) and the conventional laparoscopic-assisted approach for low rectal cancer. In the present research, we investigated the expected effect of NOSES.

Our study aimed to further explore the application value and short-term efficacy of NOSES for resecting specimens of low rectal cancer, as well as to provide a theoretical basis for its extensive clinical application.

From June 2015 to June 2018, 108 consecutive laparoscopic-assisted low rectal cancer resections were performed at our center. Among them, 26 specimens were resected transanally using a prolapsing technique (NOSES), and 82 were resected through a conventional abdominal wall small incision (LAP). A propensity score matching method was applied to select 26 pairs of matched patients, and their perioperative data were analyzed. After data matching, the baseline data were comparable between the two matched groups. All 52 patients underwent the surgery successfully.

The operative time, blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, postoperative complication rate, circumferential margin involvement, postoperative follow-up data, and postoperative anal function were not statistically significant. And NOSES had advantages in reducing postoperative pain, accelerating recovery, lowering medical costs, and improving the postoperative aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall.

NOSES for low rectal cancer can achieve satisfactory short-term efficacy. The completion of the NOSES operation requires sterility and no tumor, which requires that the surgeon must have extensive experience and enough operation skills. Surgical indications must be strictly controlled when performing this operation. Otherwise, prolonging the operation time will also increase the incidence of surgical complications.

We will spare no effort to continue the research in this field in future, and we will design high quality randomized controlled trials to explore the long-term efficacy of NOSES.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:177-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2526] [Cited by in RCA: 2935] [Article Influence: 326.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11444] [Cited by in RCA: 13319] [Article Influence: 1331.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Lacy AM, Bemelman WA, Andersson J, Angenete E, Rosenberg J, Fuerst A, Haglind E; COLOR II Study Group. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1324-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 958] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ; COlorectal cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection II (COLOR II) Study Group. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in RCA: 1246] [Article Influence: 95.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hisada M, Katsumata K, Ishizaki T, Enomoto M, Matsudo T, Kasuya K, Tsuchida A. Complete laparoscopic resection of the rectum using natural orifice specimen extraction. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16707-16713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blackmore AE, Wong MT, Tang CL. Evolution of laparoscopy in colorectal surgery: an evidence-based review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4926-4933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang XS. The present situation and prospects of colorectal tumor like-NOTES technique. Zhongguo Jiezhichang Jibing Dianzi Zazhi. 2015;4:11-16. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Zhang XM, Wang Z, Hou HR, Zhou ZX. A new technique of totally laparoscopic resection with natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) for large rectal adenoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li XW, Chen HJ, Li BH, Wang CY, Zhang JJ, Hu JH. Application of improved anvil placement in laparoscopic resection of low rectal cancer with resection of anal eversion. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2018;21:69-73. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Juul T, Ahlberg M, Biondo S, Emmertsen KJ, Espin E, Jimenez LM, Matzel KE, Palmer G, Sauermann A, Trenti L, Zhang W, Laurberg S, Christensen P. International validation of the low anterior resection syndrome score. Ann Surg. 2014;259:728-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alam AH, Soyer V, Sabuncuoglu MZ, Otan E, Kayaalp C. Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) and transanal extracorporeal anvil placement during laparoscopic low anterior resection. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:669-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Asari SA, Cho MS, Kim NK. Safe anastomosis in laparoscopic and robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a narrative review and outcomes study from an expert tertiary center. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:175-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Baek SJ, Kim J, Kwak J, Kim SH. Can trans-anal reinforcing sutures after double stapling in lower anterior resection reduce the need for a temporary diverting ostomy? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5309-5313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lamm SH, Zerz A, Efeoglou A, Steinemann DC. Transrectal Rigid-Hybrid Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Sigmoidectomy for Diverticular Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:789-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sylla P, Rattner DW, Delgado S, Lacy AM. NOTES transanal rectal cancer resection using transanal endoscopic microsurgery and laparoscopic assistance. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1205-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 545] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu W, Xu Z, Cheng H, Ying J, Cheng F, Xu W, Cao J, Luo J. Comparison of short-term clinical outcomes between transanal and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for the treatment of mid and low rectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1841-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Penna M, Hompes R, Arnold S, Wynn G, Austin R, Warusavitarne J, Moran B, Hanna GB, Mortensen NJ, Tekkis PP; International TaTME Registry Collaborative. Incidence and Risk Factors for Anastomotic Failure in 1594 Patients Treated by Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: Results From the International TaTME Registry. Ann Surg. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | D'Hoore A, Wolthuis AM, Sands DR, Wexner S. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: The Work is Progressing Well. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Tsai A, Mavroveli S, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Sietses C, Tuynman JB, Lacy AM, Hanna GB, Bonjer HJ. COLOR III: a multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing transanal TME versus laparoscopic TME for mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3210-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

STROBE Statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Eleftheriadis NP, Gkekas I, M'Koma AE, Niu ZS, Richardson WS, Slomiany BL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu YXJ