Published online Sep 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2549

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: June 19, 2019

Revised: July 6, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20, 2019

Published online: September 6, 2019

Processing time: 152 Days and 2.9 Hours

Synovial sarcoma (SS), a rare malignant soft tissue tumor whose histological origin is still unknown, often occurs in limbs in young people and is easily misdiagnosed.

We report a 24-year-old man who sought treatment for plantar pain thought to be caused by a foot injury that occurred 4 years prior. Currently, he had been seen at another hospital for a 1-wk history of unexplained pain in the left plantar region and was treated with acupuncture, a kind of therapy of Chinese medicine, which partly relieved the pain. Because of this, the final diagnosis of biphasic SS was made after two subsequent treatments by pathological evaluation after the last operation. SS is rarely seen in the plantar area, and his history of a left plantar injury confused the original diagnosis.

This study shows that pathological and imaging examinations may play a vital role in the early diagnosis and treatment of SS.

Core tip: A young male patient suffered from plantar pain for 1 wk. The symptoms were relieved after a kind of Chinese traditional invasive treatment. After that, the hemogram showed infection and magnetic resonance imaging showed that there was a soft tissue mass with a clear boundary in the plantar region. Rare location, complex medical history, invasive treatment, and auxiliary examination were easy to mislead doctors’ judgments. Finally, the diagnosis was confirmed as synovial sarcoma by pathological examination. This case suggests that when soft tissue mass is encountered, biopsy is always the gold standard and must not be missed.

- Citation: Gao J, Yuan YS, Liu T, Lv HR, Xu HL. Synovial sarcoma in the plantar region: A case report and literature review. World Journal of Clinical Cases 2019; 7(17): 2549-2555

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i17/2549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2549

Synovial sarcoma (SS) was first reported by Knox in 1936, who believed that SS originated from synovial cells[1]. In 1938, Berger defined SS as a tumor that occurred in the synovium, bursa, and tendon sheath[2]. Later, in 2013, the World Health Organization classified SS as a tumor of indefinite origin[3] that could be divided into single phase, double phase, and poorly differentiated lesions based on its pathological characteristics. SS is the fourth most common soft tissue sarcoma[4], accounting for 5%-10% of soft tissue sarcomas[5]. It often occurs in boys and men aged 15–35 years old[6,7], with a male/female ratio of about 1.2:1.0[8,9]. SS is commonly found in soft tissues around the large joints of limbs, especially in soft tissues near the knee joint [10]. A plantar SS is rare. The 5-year survival of SS patients is 61%-80%, and the 10-year survival is 10%–30%[11,12].

It has been found that SS correlates closely with translocation of chromosomes 18 and X, which generates the SYT-SSX fusion gene now existing in no other disease but SS. Therefore, the molecular cytogenetic examination of T (x; 18) (p11.2; q11.2) and SS18-SSX fusion gene transcripts has been considered the most important evidence for diagnosing SS[13]. According to reported research[14], the sensitivity of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RP-PCR) for identifying SS are, respectively, about 80.0% and 83.8%, and their combined sensitivity is about 92.9%.

At present, there is no effective cure for SS[15]. A timely, correct diagnosis and the proper surgical treatment at an early stage are essential for a good prognosis. Kartha and Bumpous[16] reported that performing an operation to remove the tumor with a diameter < 5 cm is the treatment of choice for SS. For an SS with a diameter > 5 cm, radiotherapy is needed prior to the surgery[16,17]. In addition, Eilber et al[18] reported a randomized controlled trial showing that radiotherapy after surgery for SS increased the survival rate.

In 2016, Vlenterie et al[10] analyzed 3711 SS patients, among whom 313 had advanced-stage SS. They found that about 56% of the SSs at an advanced stage originated from limbs, and pulmonary metastasis was commonly detected (80%). Compared with other soft tissue sarcomas, metastasis of SS begins at an earlier age (median age, 40 years), and men more often experience metastasis than women at the same age (male/female = 191:122).

SS is sensitive to chemotherapy and has a better prognosis than other sarcomas at the same stage[9]. Recent research showed that chemotherapy for metastatic SS tumor with ifosfamide or doxorubicin could protract patients’ lives, whereas radiotherapy had no positive effect on patients’ prognosis[19]. Trabectedin, a novel, targeted anti-tumor, cytotoxic drug, has been approved in Europe for treating advanced liposar-comas and leiomyosarcomas[20]. Japanese researchers have shown that trabectedin plays a prominent role in repressing the growth of SS cells and has potential for use clinically in the treatment of SS[21]. Surgery combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy as comprehensive treatment for SS in current clinical practice may hopefully improve the survival rate of patients with SS.

We describe herein a case of SS in the plantar region of the foot misdiagnosed due to the patient’s complicated history of plantar trauma and repeated treatment for this atypical manifestation. The patient was misdiagnosed in different hospitals as having plantar fasciitis, soft tissue infection, and inflammatory granuloma. We assess the reason for these misdiagnoses and finally conclude that when a patient’s symptoms are not typical and evidence of the imaging examination is insufficient, a pathological examination is essential for a timely, correct diagnosis, which should be established as early as possible.

A 24-year-old man had a 4-year history of a left plantar injury from which he recovered within several days without treatment and with no mobility obstacles.

Currently, the patient suffered unexplained pain during walking in his left plantar region for almost a week. He noted some swelling in the left plantar area but no fever, chills, or pain. He took some nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which partly relieved his walking-induced pain. The pain recurred within 3 d, however, at which time he visited a hospital where he was treated with acupuncture. The pain was once again relieved, although 2 d later it returned, hampering his mobility. He was brought to our hospital in an armchair (Peking University People’s Hospital).

Since the onset of his walking pain, the patient had experienced no problems with his mental state, diet, sleeping, or weight.

The family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed some swelling in his left plantar region and ecchymosis (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm) with accompanying tenderness at that site. When he back-stretched his left foot, the fourth toe had sharp pain. No mass was found in his left plantar area.

Routine blood examination showed a white blood cell count of 10.06×109/L and C-reactive protein level was 9.51 mg/L.

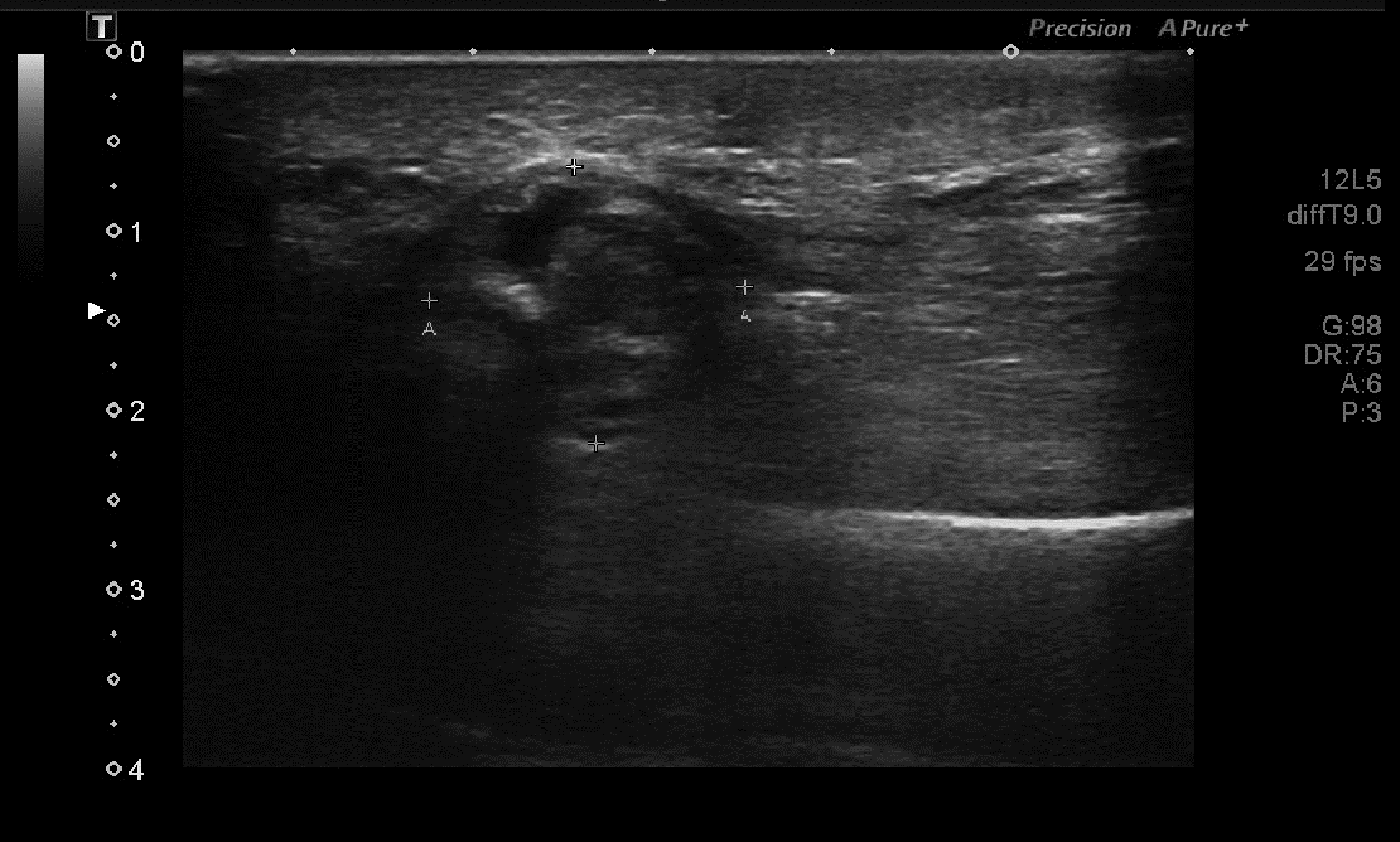

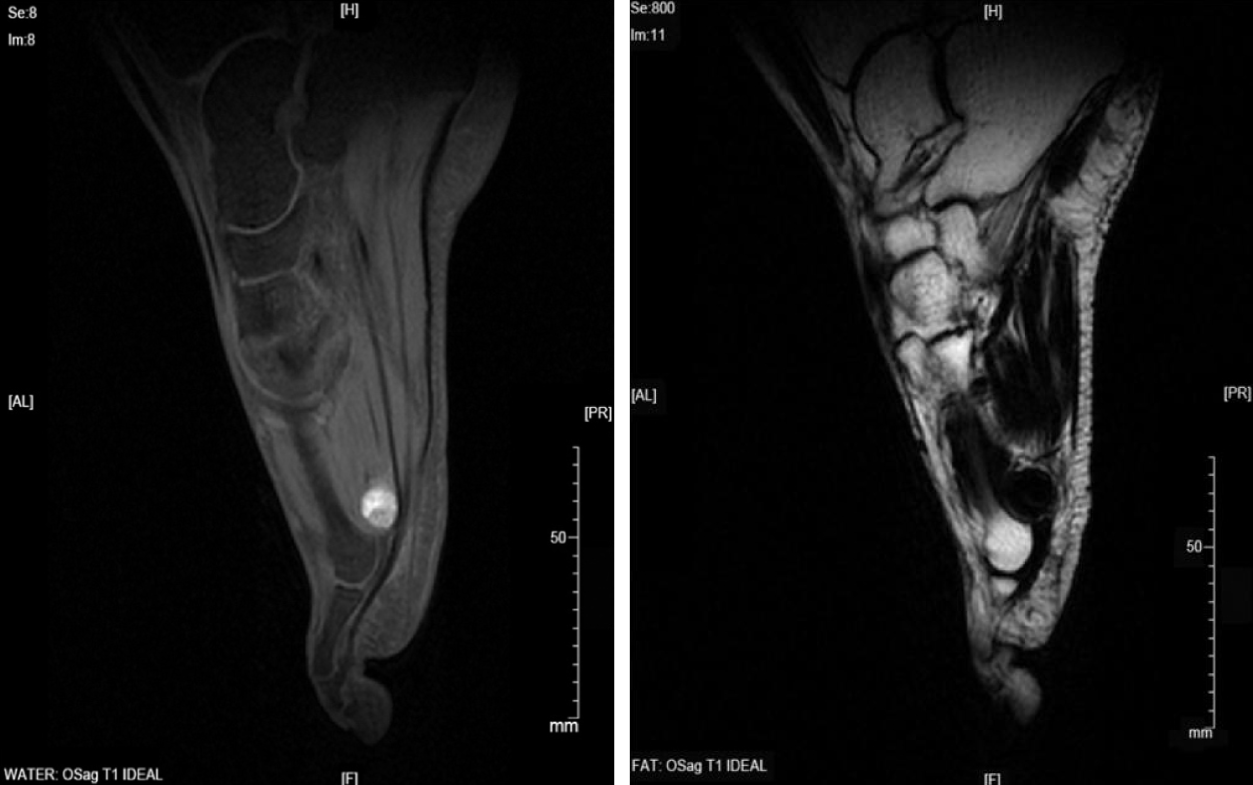

Plain radiography of his left plantar was normal (Figure 1). Color Doppler ultraso-nography showed an inhomogeneous mass in the plantar area of the left foot (Figure 2), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested that it could be a benign tumor or tumor-like lesion, such as inflammatory granulation or a giant cell tumor in the tendon sheath (Figure 3).

Taking into account the patient's disease history, symptoms, and examination findings, however, his suspected diagnosis was a soft tissue infection in the left plantar area.

He was treated with antibiotics (cefuroxime, 1500 mg, bid, i.v.) for 3 d, which relieved the walking-induced pain, and his laboratory values returned to normal, with a white blood cell count of 6.90 × 109/L and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 7 mm/h. He was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 7 and continued to take cefuroxime orally as directed.

On day 11 after his discharge, his pain recurred, and he was again admitted to our hospital, this time demanding that we remove the mass in his left plantar region. Physical examination showed a swelling in the left plantar area and ecchymosis (1.5 cm2 × 1.5 cm2) in the left plantar region with accompanying tenderness (Figure 4). The mass had no clear margins with its surroundings, and the blood supply and nerves of the left plantar area were normal. We removed the mass on day 2 after admission, then used cefuroxime infusion as his last hospital stay. The lesion measured 3.0 cm × 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm and was elliptical, lobulated, yellowish gray, and soft (like adipose tissue). It had been located between the foot plantar flexion tendons and metatarsal with clear boundaries.

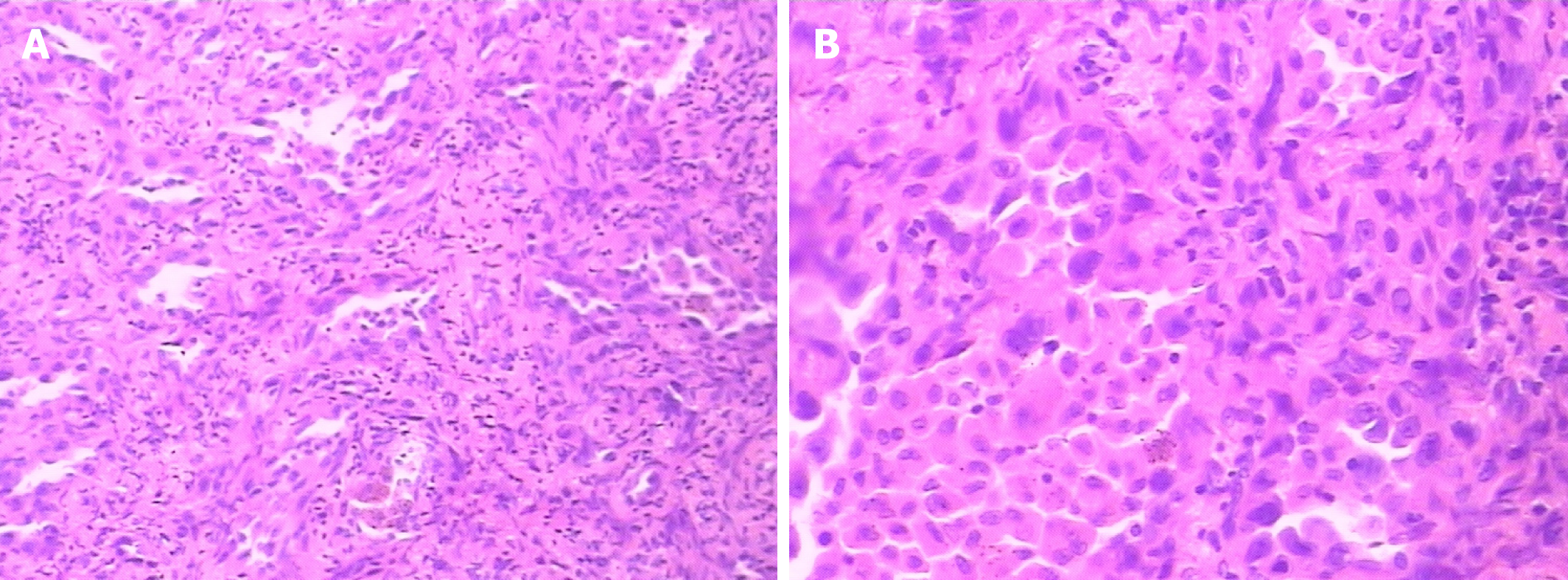

Postoperative pathological examination showed a focal adenoid structure, composed partly of interstitial fibrosis and multinucleated giant cells with scattered hemosiderin deposition. The HE staining showed a sign of tumor cell type (Figure 5). Immunohistochemical staining showed the following: CK (adenoid area) (+), CK7 (adenoid area) (+), desmin (−), CD34 (blood vessels) (+), TLE1 (+), S100 (−/+), P63 (−), KP-1 (coenocytes) (+), and KP-1 (+5%). The pathological diagnosis was SS (bipolar).

This patient received postoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cyclo-phosphamide for 2 mo, after which no metastasis was found.

This case of SS, with a 4-year history of plantar trauma, the inflammatory symptoms during the treatment, and the indication of a benign mass without a clear boundary on imaging, was easily misdiagnosed. Typical SSs are commonly found in deep soft tissue and manifest as a large mass with slow growth. In addition, they most often are accompanied by focal pain or tenderness. The average incubation of SS is 2-4 years, with some even reaching 20 years[22]. The patient discussed herein had an SS in his left plantar region after having experienced plantar trauma 4 years prior. In addition, his symptoms had not presented until about 2 wk before his first visit to the hospital complaining of plantar pain.

Walking-induced pain in the left plantar region in a patient with a history of plantar trauma 4 years prior is not commonly related to a malignant tumor, which caused the misdiagnosis at his first visit. When he was admitted to our hospital, the laboratory and imaging examinations suggested a benign mass due to infection that may have been caused by his prior acupuncture treatment. Thus, he was mis-diagnosed as having a left plantar infection, which was relieved by the prescribed antibiotic treatment. When he returned a few days later, combined with the surgical findings, he was misdiagnosed a second time as having an inflammatory granuloma in the left plantar region. The patient was finally diagnosed correctly during the pathological examination as having SS. Without a pathological examination, SS of this kind could easily to be misdiagnosed, which could cause a great loss of the patient’s quality of life.

The mechanism of SS is not fully understood. A few cases have been reported in which SS may have a correlation with the use of radiotherapy[23,24], and some believe that calcified SS may be related to trauma. Murphey et al[4], however, argued that trauma has nothing to do with SS and that SS causes some clinical symptoms that might increase the possibility of discovering it after trauma. Regretfully, in this case, the patient did not seek for medical help immediately, so no imaging details were available to study whether the plantar trauma that occurred 4 years prior was related to the development of the SS.

To better understand SS, we searched PubMed for articles about SS published from 1953 to 2017. We found that, except liposarcoma, almost all other soft tissue sarcomas lack peculiar manifestations during imaging examinations, and the diagnostic rate for SS is just 25%[25]. The images of SS have no apparent specificity, although there are some peculiar manifestations[26,27]. SS commonly manifests on computed tomography (CT) as a heterogeneous mass with low density and inapparent boundaries compared with the normal surrounding tissues. These characteristics may be intensified by different degrees with enhanced CT. On MRI, SS manifests as having clear boundaries and swelling around the mass, mainly equivalent signals on T1-weighted images (mixed with some higher signals) and compound signals in T2-weighted images[4,28], and this is one of the reasons for misdiagnosing SS as a benign tumor. Therefore, whether there is a clear boundary cannot be regarded as proof for distinguishing whether a mass is benign or malignant or the degree of histological differentiation[29,30].

The MRI results in this case conform to the characteristics reported above (i.e., a round mass with a clear boundary and compound signals on T2-weighted images), ensuring its easy diagnosis as a benign tumor. Under such a circumstance, CT should be performed to further determine if it might be SS. If the results do not clearly indicate that it is SS, a pathological examination for the correct diagnosis is needed.

| 1. | Jung SC, Choi JA, Chung JH, Oh JH, Lee JW, Kang HS. Synovial sarcoma of primary bone origin: a rare case in a rare site with atypical features. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Berger L. Synovial sarcomas in serous bursae and tendon sheaths. Am J Cancer. 1938;34:501-539. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Frank GA, Andreeva YY, Moskvina LV, Efremov GD, Samoilova SI. A new WHO classification of prostate tumors. Arkh Patol. 2016;78:32-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. From the archives of the AFIP: Imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26:1543-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beck SE, Nielsen GP, Raskin KA, Schwab JH. Intraosseous synovial sarcoma of the proximal tibia. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:184891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Scheithauer BW, Silva AI, Kattner K, Seibly J, Oliveira AM, Kovacs K. Synovial sarcoma of the sellar region. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:454-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jeganathan R, Davis R, Wilson L, McGuigan J, Sidhu P. Primary mediastinal synovial sarcoma. Ulster Med J. 2007;76:109-111. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Thway K, Fisher C. Synovial sarcoma: defining features and diagnostic evolution. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18:369-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Deshmukh R, Mankin HJ, Singer S. Synovial sarcoma: the importance of size and location for survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;155-161. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Vlenterie M, Litière S, Rizzo E, Marréaud S, Judson I, Gelderblom H, Le Cesne A, Wardelmann E, Messiou C, Gronchi A, van der Graaf WT. Outcome of chemotherapy in advanced synovial sarcoma patients: Review of 15 clinical trials from the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group; setting a new landmark for studies in this entity. Eur J Cancer. 2016;58:62-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shi W, Indelicato DJ, Morris CG, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP, Zlotecki RA. Long-term treatment outcomes for patients with synovial sarcoma: a 40-year experience at the University of Florida. Am J Clin Oncol. 2013;36:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haldar M, Randall RL, Capecchi MR. Synovial sarcoma: from genetics to genetic-based animal modeling. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2156-2167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Romeo S, Rossi S, Acosta Marín M, Canal F, Sbaraglia M, Laurino L, Mazzoleni G, Montesco MC, Valori L, Campo Dell'Orto M, Gianatti A, Lazar AJ, Dei Tos AP. Primary Synovial Sarcoma (SS) of the digestive system: a molecular and clinicopathological study of fifteen cases. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Kanemitsu S, Hisaoka M, Shimajiri S, Matsuyama A, Hashimoto H. Molecular detection of SS18-SSX fusion gene transcripts by cRNA in situ hybridization in synovial sarcoma using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue specimens. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2007;16:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen Y, Yang Y, Wang C, Shi Y. Adjuvant chemotherapy decreases and postpones distant metastasis in extremity stage IIB/III synovial sarcoma patients. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kartha SS, Bumpous JM. Synovial cell sarcoma: diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1979-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ranchère-Vince D. Soft tissue tumors: how to manage the biopsy and the surgical specimen? Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:717-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Eilber FC, Brennan MF, Eilber FR, Eckardt JJ, Grobmyer SR, Riedel E, Forscher C, Maki RG, Singer S. Chemotherapy is associated with improved survival in adult patients with primary extremity synovial sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Scheer M, Dantonello T, Hallmen E, Vokuhl C, Leuschner I, Sparber-Sauer M, Kazanowska B, Niggli F, Ladenstein R, Bielack SS, Klingebiel T, Koscielniak E. Primary Metastatic Synovial Sarcoma: Experience of the CWS Study Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Le Loarer F, Zhang L, Fletcher CD, Ribeiro A, Singer S, Italiano A, Neuville A, Houlier A, Chibon F, Coindre JM, Antonescu CR. Consistent SMARCB1 homozygous deletions in epithelioid sarcoma and in a subset of myoepithelial carcinomas can be reliably detected by FISH in archival material. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:475-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yasui H, Imura Y, Outani H, Hamada K, Nakai T, Yamada S, Takenaka S, Sasagawa S, Araki N, Itoh K, Myoui A, Yoshikawa H, Naka N. Trabectedin is a promising antitumour agent for synovial sarcoma. J Chemother. 2016;28:417-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bakri A, Shinagare AB, Krajewski KM, Howard SA, Jagannathan JP, Hornick JL, Ramaiya NH. Synovial sarcoma: imaging features of common and uncommon primary sites, metastatic patterns, and treatment response. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W208-W215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Egger JF, Coindre JM, Benhattar J, Coucke P, Guillou L. Radiation-associated synovial sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of two cases. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:998-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Deraedt K, Debiec-Rychter M, Sciot R. Radiation-associated synovial sarcoma of the lung following radiotherapy for pulmonary metastasis of Wilms' tumour. Histopathology. 2006;48:473-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Brisse HJ, Orbach D, Klijanienko J. Soft tissue tumours: imaging strategy. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1019-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liang C, Mao H, Tan J, Ji Y, Sun F, Dou W, Wang H, Wang H, Gao J. Synovial sarcoma: Magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging features and differential diagnostic considerations. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Alhazzani AR, El-Sharkawy MS, Hassan H. Primary retroperitoneal synovial sarcoma in CT and MRI. Urol Ann. 2010;2:39-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tang YM, Stuckey S, Lambie D, Strutton GM. Macroscopic vascular invasion in synovial sarcoma evident on MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:783-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fedors NH, Demos TC, Lomasney LM, Mehta V, Horvath LE. Radiologic case study: your diagnosis? Synovial sarcoma. Orthopedics. 2010;33:861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kadapa NP, Reddy LS, Swamy R, Kumuda, Reddy MV, Rao LM. Synovial sarcoma oropharynx - a case report and review of literature. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2014;5:75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Melo FF S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX