Published online Jan 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.109

Peer-review started: September 4, 2018

First decision: October 12, 2018

Revised: October 25, 2018

Accepted: December 7, 2018

Article in press: December 8, 2018

Published online: January 6, 2019

Processing time: 122 Days and 21.1 Hours

Ganglioneuroma (GN) is a rare and benign tumor that originates from autonomic nervous system ganglion cells. The most frequently involved sites are the posterior mediastinum, the abdominal cavity, and the retroperitoneal space. It rarely occurs in the cervical area, compressing the spinal cord. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) is an autosomal dominant inheritance disorder, whose prevalence rate approximates one per 3000.

We report an extremely rare case of bilateral and symmetric dumbbell GNs of the cervical spine with NF-1. A 27-year-old man with NF-1 presented with a one-year history of gradually progressive right upper extremity weakness and numbness in both hands. Magnetic resonance imaging showed bilateral and symmetric dumbbell lesions at the C1-C2 levels compressing the spinal cord. We performed total resection of bilateral tumors, and the postoperative histopathological diagnosis of the resected mass was GN. After operation, the preoperative symptoms were gradually relieved without complications. To our knowledge, this is the sixth report of cervical bilateral dumbbell GNs.

In some cases, cervical bilateral dumbbell GNs could be associated with NF-1. The exact diagnosis cannot be obtained before operation, and pathological outcome is the current gold standard. Surgical resection is the most effective option, and disease outcome is generally good after treatment.

Core tip: Ganglioneuroma is the final mature form of neuroblastic tumors which mainly involves the posterior mediastinum and the retroperitoneal space. We report a rare case of cervical bilateral dumbbell ganglioneuromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Only five cases have been reported. Due to non-specific symptoms, signs, and radiological images, it is difficult to make a definite diagnosis before postoperative pathology. The prognosis of this tumor is good. Complete resection is the exhaustive treatment. Furthermore, incomplete resection does not increase the risk of progression if tumor residuals are smaller than 2 cm.

- Citation: Tan CY, Liu JW, Lin Y, Tie XX, Cheng P, Qi X, Gao Y, Guo ZZ. Bilateral and symmetric C1-C2 dumbbell ganglioneuromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 1: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(1): 109-115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i1/109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.109

Ganglioneuroma (GN) is a rare, slow-growing, fully-differentiated tumor originating from neural crest cells of sympathetic ganglia or the adrenal medulla, with 60% occurring in children and young adults[1-3]. This benign tumor can arise de novo or results from neuroblastoma maturation (spontaneous remission phenomenon), spontaneously or following chemotherapy/radiotherapy[4]. Histologically, it comprises mature Schwann cells, ganglion cells, the fibrous tissue, and nerve fibers[5]. The most common anatomical sites include the posterior mediastinum (41.5%), the abdominal cavity including adrenal glands (21%), and the retroperitoneal space (37.5%)[6]. However, the tumor may occur in any location containing sympathetic nervous system cells, such as trigeminal GN reported by Deng et al[7] and GN of the external auditory canal and middle ear published by Almofada et al[8]. Occasionally, it grows into the spinal canal and causes heavy compression. Generally, GN is unilateral and solitary. Here, we report an extremely rare case with bilateral and symmetric dumbbell GNs of the cervical spine associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1). NF-1, also known as von Recklinghausen disease, is usually present during the first decade of life. The diagnostic criteria for NF-1 were established by the National Institutes of Health[9]. The most common benign tumor in NF-1 is neurofibroma[10,11]. To the best of our knowledge, only five cases with bilateral and dumbbell GNs of the cervical spine have been previously reported in the English literature, including two associated with NF-1[1-3,12,13]. The purpose of this report is to present an additional case and discuss the related clinical features, diagnosis methods, surgical choice, and prognosis.

A 27-year-old man was referred to the Department of Neurosurgery of The First Hospital of China Medical University, presenting with a one-year history of gradually progressive right upper extremity weakness and numbness in both hands. One month previously, his parents found him walking unsteadily and turning aside. Physical examination revealed multiple coffee spots, cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas. He had no family history of neurofibromatosis. Upon neurologic examination, muscular strengths of right and left limbs were graded as 4- and 4, respectively. Muscular tensions at both lower extremities were increased slightly, and deep reflexes were also hyperactive. Additionally, incomplete sensory loss below C3 was observed.

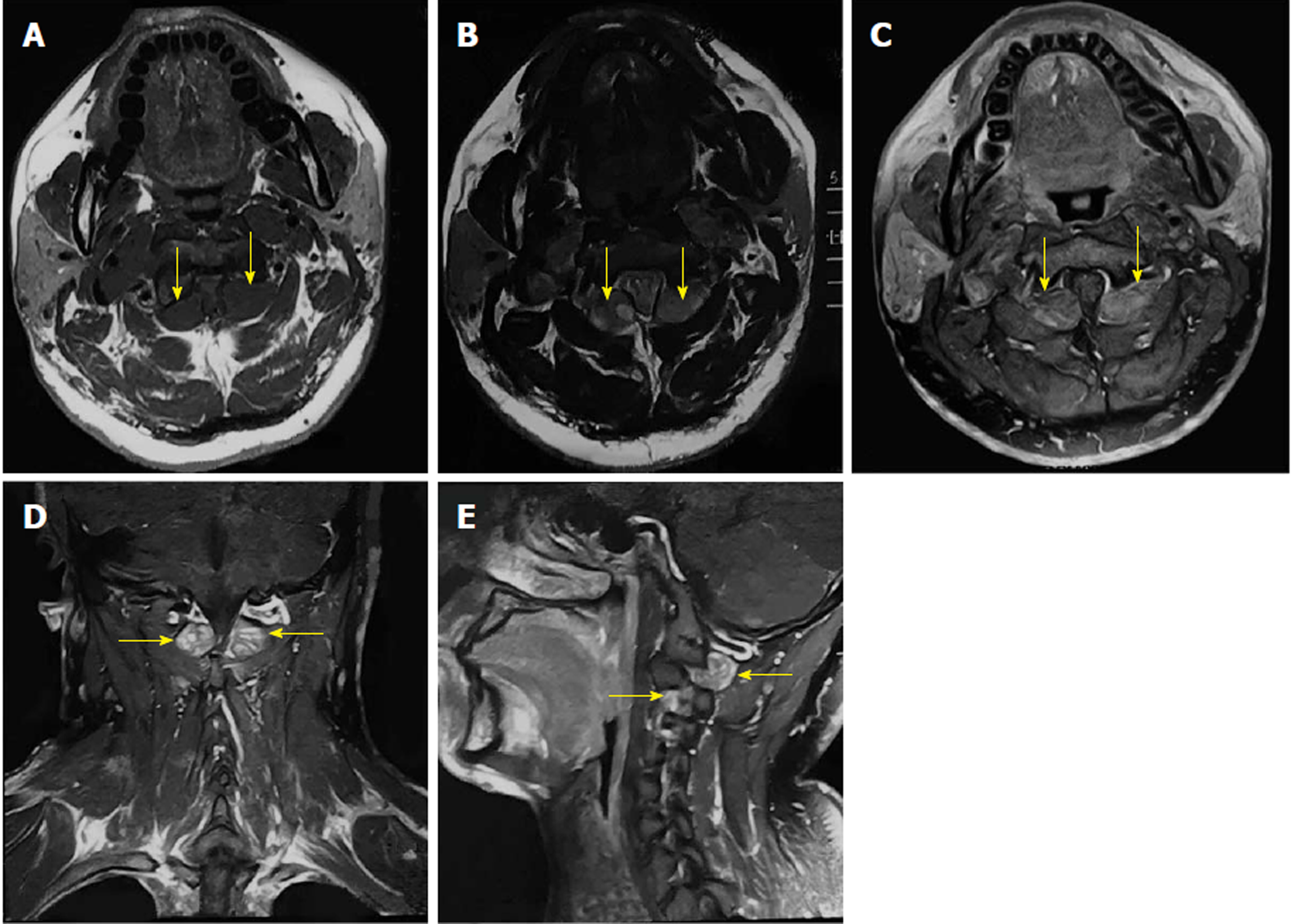

On cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we found multiple nodules around the periphery of bilateral carotid and vertebral arteries, which demonstrated low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, slightly high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and intense contrast enhancement. The spinal cord signal intensity increased at the C2 level due to compression. The bilateral intervertebral foramina at the C2-4 levels were expanded, with unusual soft tissue signal extending outside (Figure 1).

The patient underwent surgical decompression of the spinal cord in the prone position through posterior midline incision. After biting off the spinous process at the C2 level and the vertebral plate at the C1-2 levels, bilateral nerve root cuffs at the intervertebral foramen at the C1-2 levels were distended, crimping the dorsal dural sac. Then, the bilateral nerve root cuffs were incised, revealing a hard and tough reddish tumor. After total resection of the tumor piece by piece, dural sac compression was relieved. The dural sac was curved. Finally, we explored the subdural cavity, and no residual tumor was found.

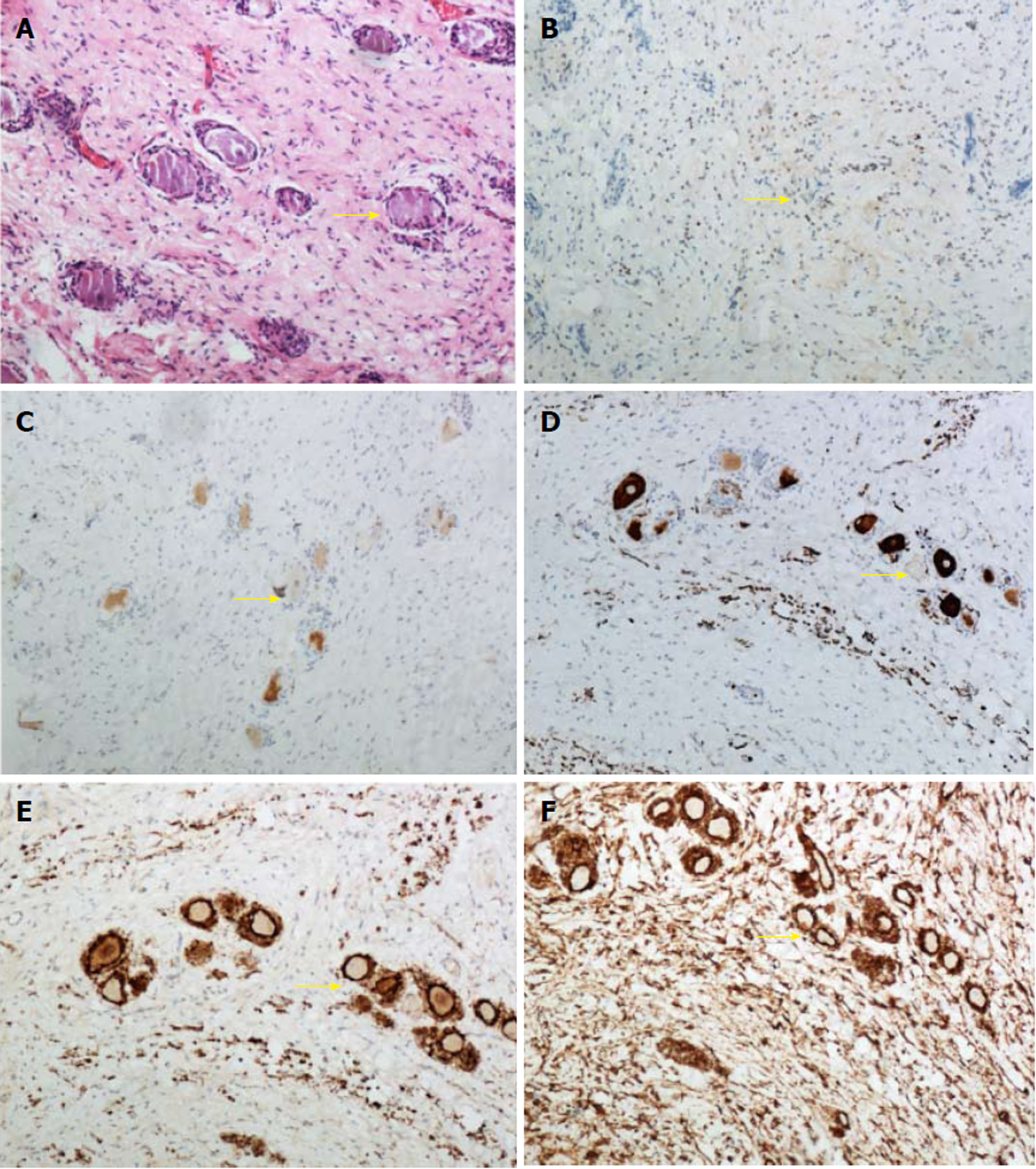

Under a light microscope, tumor cells were spindle-shaped, with nearly the same size. The nucleus was fusiform, mitosis was rare, and ganglion cells were scattered in the tumor tissue. Immunohistochemistry showed S-100 (+), vimentin (+), NF (Scattered+), NeuN (Scattered+) and the Ki67 labeling index of 3% (Figure 2). Based on the above observations, the mass was diagnosed as GN.

Bilateral and symmetric dumbbell GNs of the cervical spine with NF-1.

The patient underwent surgical decompression of the spinal cord in the prone position through posterior midline incision.

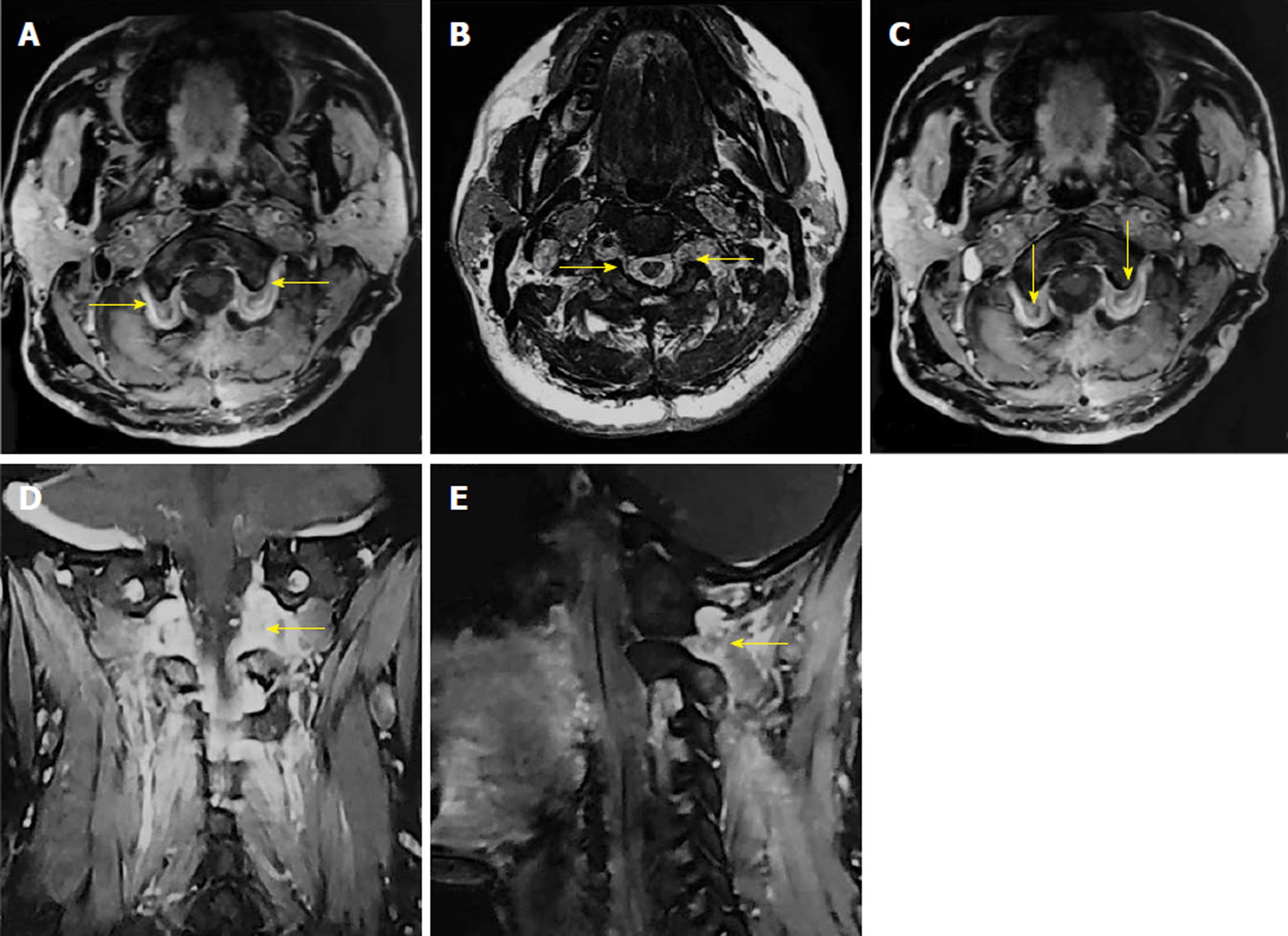

The postoperative period was uneventful, with no neurological deficits. The preoperative symptoms of the patient were gradually relieved within a week. After a month, the patient returned to our hospital with a postoperative MRI scan showing total resection of bilateral tumors, with no recurrence (Figure 3).

GN was first described in 1870[14]. Since then, an increasing number of related case reports have been published, providing comprehensive data and knowledge. GN incidence is not well documented, although reports suggested that it may account for 0.1 to 0.5% of central nervous system tumors[15]. GN rarely involves the cervical region, compressing the spinal cord. Meanwhile, bilateral dumbbell GNs with NF-1 in the cervical region are even rarer. Only five cases have been reported in the current English literature (Table 1). Of these cases, three showed intradural extension and two displayed extradural growth; the current case also involved the extradural space. However, in the majority of cases whether multiple or single, given that these tumors originate from sensory root ganglions, extradural extension from the intervertebral foramen is more common. Stout et al[16] reported a male/female ratio of GN of approximately 2/3, but the cases summarized here were all male and NF-1 is irrespective of gender or ethnicity[17]. Whether gender difference exists in GN remains unknown. Weiss reported that GN is most frequently diagnosed in patients aged between 10 and 29 years[18]. The mean age at diagnosis of our six cases was 37 years, ranging from 15 to 72 years. This difference may be associated with symptom severity and patient enthusiasm for the hospital. Besides, NF-1 is usually present during the first decade of life and malignancies occur up to four to six times more common in patients with NF-1 than in the general population[9]. Therefore, GN associated with NF-1 seems to be more likely to diagnose earlier.

| Ref. | Age/Sex | Extension | Site | Treatment | NF-1 | Presentation | Prognosis | Follow-up imaging |

| Hioki et al[12] | 72/male | Intradural/extradural | C1-2 | PR | - | Tetraparesis; sensory dysfunction | Symptom remission | No recurrence or increase after 2 yr |

| Kyoshima et al[3] | 35/male | Intradural/extradural | C2-3 | PR | + | Tetraparesis; respiratory dysfunction | Hypesthesia | None |

| Miyakoshi et al[2] | 15/male | Extradural | C1-2; C3-4 | PR | + | Tetraparesis; sensory dysfunction | Symptom remission | No recurrence or increase after 2 yr |

| Ugarriza et al[1] | 53/male | Extradural | C2 | TR | - | Tetraparesis; respiratory dysfunction; sensory dysfunction | Tetraparesis | None |

| Ando Hioki et al[13] | 20/male | Intradural/extradural | C1-2; C2-3; C3-4 | PR | - | Tetraparesis; sensory dysfunction | Symptom remission | No recurrence or increase after 2 yr |

The tumor is hardly symptomatic or completely asymptomatic depending on its location. According to previous reports, only 10% of GNs may involve the spinal canal[19]. With tumor growth in the spinal canal, a series of compression symptoms may occur. In the six cases, tetraparesis caused by compression to the spinal cord from bilateral masses was the most frequent symptom, and commonly appeared earlier. Sensory dysfunction may also be involved. With time, some patients may develop respiratory problems. Intriguingly, few patients feel pain in the neck or develop palpable masses. In addition, a few tumors exhibit hormone secretion activity, presenting a broad range of symptoms depending on the hormones produced, e.g., catecholamine production causes hypertension, vasoactive intestinal peptide secretion results in diarrhea, and estrogen production causes female secondary sex characteristic and rophany[3]. Recently, we have demonstrated metaiodobenzylguanidine uptake and elevated catecholamine metabolite amounts in urine[20]. These characteristics may be used as tools for differential diagnosis.

It remains challenging to diagnose GN before operation because of non-specific features. MRI is a relatively accurate diagnostic tool for preoperative identification. Commonly, this tumor has the following manifestations: clearly defined boundary, encapsulation, homogeneous low or intermediate signal intensity in T1-weighted images and heterogeneous intermediate or high signal intensity in T2-weighted images. Besides, it exhibits slight, heterogeneous contrast enhancement. However, in many GN reports, MRI signals are not consistent. Reports analyzed and explained the relationship between the histological structure of this tumor and MRI manifestations. Interestingly, different Schwann’s cell, ganglion cell, collagen fiber, fat tissue, or myxomatous stroma proportions within the tumor cause imaging differences[21]. Recently, diffusion-weighted MRI has been reported to be useful in differentiating benign and malignant paraspinal peripheral nerve sheath tumors. In their work, the apparent diffusion coefficient value of schwannomas is higher than that of neurofibromas because neurofibromas are more cellular tumors than schwannomas[22].

As a subgroup of neuroblastic tumors, which range from immature, undifferentiated to mature, differentiated tumors, GN is the final mature form according to the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification[23]. Although it is a benign lesion, progression, late relapse, and even malignant transformation have also been reported[24,25]. Thus, long-term radiological follow-up is essential. Resection is currently the most direct and effective treatment option for such lesions. The six cases reported all underwent operation; of these, two reached complete excision, including the present one. None of the six patients developed complications. Postoperative quality of life was better than preoperative one in all the cases. Considering the purpose of the surgical treatment was to decompress the spinal cord, in some cases it is not necessary to achieve total resection, e.g., when the paraspinal portion of the tumor causes no symptoms. Instead, performing total resection blindly may affect spine cord stability and even injure it, causing severe complications. A more cautious surgical approach in such situations should be suggested[26]. Furthermore, incomplete resection does not increase the risk of progression when the residual tumor is smaller than 2 cm[20]. Large residual tumors with local progression may contain immature components. Therefore, how to ensure that immature components are removed during the initial surgery appears to be particularly important. Recently, biopsy has been used in GN diagnosis, but it is not always reliable and even misleading preoperatively. Whether it could help define prognosis after operation is worth investigating. Postoperative chemotherapy seems not to be sufficient in previously reported patients[20].

In conclusion, cervical bilateral dumbbell GNs causing spinal cord compression with associated symptoms are extremely rare. In some cases, such tumors could be associated with NF-1. The exact diagnosis cannot be obtained before operation, and pathological outcome is the current gold standard. Surgical resection is the most effective option, and disease outcome is generally good after treatment.

The patient in our case underwent total resection, but we suggest it is not necessary to reach complete resection by literature review. Our study demonstrates that this tumor has a good prognosis after operation and total resection is not necessary.

| 1. | Ugarriza LF, Cabezudo JM, Ramirez JM, Lorenzana LM, Porras LF. Bilateral and symmetric C1-C2 dumbbell ganglioneuromas producing severe spinal cord compression. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:228-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kasukawa Y, Misawa A, Shimada Y. Bilateral and symmetric C1-C2 dumbbell ganglioneuromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 causing severe spinal cord compression. Spine J. 2010;10:e11-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kyoshima K, Sakai K, Kanaji M, Oikawa S, Kobayashi S, Sato A, Nakayama J. Symmetric dumbbell ganglioneuromas of bilateral C2 and C3 roots with intradural extension associated with von Recklinghausen’s disease: case report. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:468-473; discussion 473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dąbrowska-Thing A, Rogowski W, Pacho R, Nawrocka-Laskus E, Nitek Ż. Retroperitoneal Ganglioneuroma Mimicking a Kidney Tumor. Case Report. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:283-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Geoerger B, Hero B, Harms D, Grebe J, Scheidhauer K, Berthold F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer. 2001;91:1905-1913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lonergan GJ, Schwab CM, Suarez ES, Carlson CL. Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:911-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Deng X, Fang J, Luo Q, Tong H, Zhang W. Advanced MRI manifestations of trigeminal ganglioneuroma: a case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Almofada HS, Timms MS, Dababo MA. Ganglioneuroma of the External Auditory Canal and Middle Ear. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:4736895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Razek AAKA. MR imaging of neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the brain and spine in neurofibromatosis type I. Neurol Sci. 2018;39:821-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Varan A, Şen H, Aydın B, Yalçın B, Kutluk T, Akyüz C. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and malignancy in childhood. Clin Genet. 2016;89:341-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Mautner VF, Cooper DN. Emerging genotype-phenotype relationships in patients with large NF1 deletions. Hum Genet. 2017;136:349-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hioki A, Miyamoto K, Hirose Y, Kito Y, Fushimi K, Shimizu K. Cervical symmetric dumbbell ganglioneuromas causing severe paresis. Asian Spine J. 2014;8:74-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ando K, Imagama S, Ito Z, Hirano K, Tauchi R, Muramoto A, Matsui H, Matsumoto T, Ishiguro N. Cervical myelopathy caused by bilateral C1-2 dumbbell ganglioneuromas and C2-3 and C3-4 neurofibromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19:676-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Baty JA, Ogilvie ND, Symons M. Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Br J Surg. 2010;49:409-414. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Choi YH, Kim IO, Cheon JE, Kim WS, Yeon KM, Wang KC, Cho BK, Chi JG. Gangliocytoma of the spinal cord: a case report. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:377-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | STOUT AP. Ganglioneuroma of the sympathetic nervous system. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84:101-110. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pasmant E, Parfait B, Luscan A, Goussard P, Briand-Suleau A, Laurendeau I, Fouveaut C, Leroy C, Montadert A, Wolkenstein P, Vidaud M, Vidaud D. Neurofibromatosis type 1 molecular diagnosis: what can NGS do for you when you have a large gene with loss of function mutations? Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:596-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hoda SA. Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2014;21:216. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pang BC, Tchoyoson Lim CC, Tan KK. Giant spinal ganglioneuroma. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:967-972. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Decarolis B, Simon T, Krug B, Leuschner I, Vokuhl C, Kaatsch P, von Schweinitz D, Klingebiel T, Mueller I, Schweigerer L, Berthold F, Hero B. Treatment and outcome of Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang Y, Nishimura H, Kato S, Fujimoto K, Ohkuma K, Kojima K, Uchida M, Hayabuchi N. MRI of ganglioneuroma: histologic correlation study. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:617-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Razek AAKA, Ashmalla GA. Assessment of paraspinal neurogenic tumors with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:841-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Shimada H, Ambros IM, Dehner LP, Hata J, Joshi VV, Roald B. Terminology and morphologic criteria of neuroblastic tumors: recommendations by the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee. Cancer. 1999;86:349-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Moschovi M, Arvanitis D, Hadjigeorgi C, Mikraki V, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F. Late malignant transformation of dormant ganglioneuroma? Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kulkarni AV, Bilbao JM, Cusimano MD, Muller PJ. Malignant transformation of ganglioneuroma into spinal neuroblastoma in an adult. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:324-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | De Bernardi B, Gambini C, Haupt R, Granata C, Rizzo A, Conte M, Tonini GP, Bianchi M, Giuliano M, Luksch R, Prete A, Viscardi E, Garaventa A, Sementa AR, Bruzzi P, Angelini P. Retrospective study of childhood ganglioneuroma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1710-1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P- Reviewer: Bhalla AS, Razek AA, Sijens PE S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Bian YN