Published online Jun 16, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i6.121

Peer-review started: January 14, 2018

First decision: February 9, 2018

Revised: April 8, 2018

Accepted: April 16, 2018

Article in press: April 17, 2018

Published online: June 16, 2018

Processing time: 159 Days and 3.4 Hours

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma is uncommon in children population. There were few cases reported in the literature with wide range clinical presentations including advanced stage, and more involvement of liver, spleen and bone marrow. Head and neck lymphadenopathy tends to present in younger children. We report a case of 10-year-old boy who initially presented intermittent fever, headaches and neck lymphadenopathy. Subsequently, he developed diffuse lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma was diagnosed on a cervical lymph node biopsy. Cervical lymphadenopathy in this age group is most commonly reactive or non-malignant processes. Lymphoma is much less frequent; mainly are non-Hodgkin lymphomas. However, a subset of large B-cell lymphoma called T-cell/histiocyte- rich B-cell lymphoma is rare in children.

Core tip: We report a case of a 10-year-old boy presenting with intermittent fevers, fatigue, weight loss, and head and neck lymphadenopathy. A cervical lymph node biopsy revealed scattered large neoplastic cells surrounded by small reactive lymphocytes and histiocytes without residual germinal center meshwork. These pathologic features are consistent with T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL) which tends to be rare in the pediatric population and can be easily missed leading to inappropriate treatment and poorer outcome. Therefore, THRLBCL should be consisted as a differential diagnosis for persistent lymphadenopathy in the pediatric population.

- Citation: Wei C, Wei C, Alhalabi O, Chen L. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma in a child: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(6): 121-126

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i6/121.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i6.121

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL) was originally described by Ramsay et al[1] in 1988 as a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. It is characterized by scattered neoplastic large B-cells with predominant small reactive T-cells and histiocytes in the background, and an absence of follicular dendritic meshworks[2]. THRLBCL is most commonly seen in older people and rarely seen in the pediatric population[3]. It can be easily misdiagnosed for a classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) or nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL); or not considered in the differential diagnosis for lymphadenopathy (LAD) in a child.

We describe a case of a 10-year-old boy with intermittent fevers, headache, weight loss, and head and neck lymphadenopathy. A cervical lymph node biopsy showed scattered large neoplastic cells in the background of small reactive lymphocytes and histiocytes without germinal center meshwork; with features were consistent with THRLBCL.

A 10-year-old previously health boy initially presented with intermittent headache, fever, and cough for few months. He was seen by his pediatrician and symptoms were thought to be infectious in nature. His headaches and fevers persisted for several weeks despite supportive management with hydration and antipyretics. Two months after initial presentation, he was seen by a neurologist for his headaches. He was diagnosed with migraine like headaches and given a course of steroids with minimal improvement. Later, he developed neck lymph nodes swelling and nausea/vomiting. His mother noticed that he had lost weight (3 kg) and fatigue, and the neck lesions increased in size and number. Three months after initial presentation, he was admitted to the hospital and physical exam revealed multilevel neck lymphadenopathy (in range of 1-2 cm), significant splenomegaly, and swelling in both lower extremities. Labs demonstrated significant anemia with a hemoglobin of 6 g/dL. MRI of the abdomen showed significant, small bilateral pleural effusions, splenomegaly of 19 cm and multiple retroperitoneal nodes. A left cervical lymph node excisional biopsy was done.

A small cervical lymph node was received in pathology department, measuring 1.2 cm × 1.2 cm × 0.2 cm. A portion of the lymph node was sent for flow cytometric analysis as routine lymphoma protocol. A result of flow cytometry was noncontributory; no aberrant lymphoid population identified.

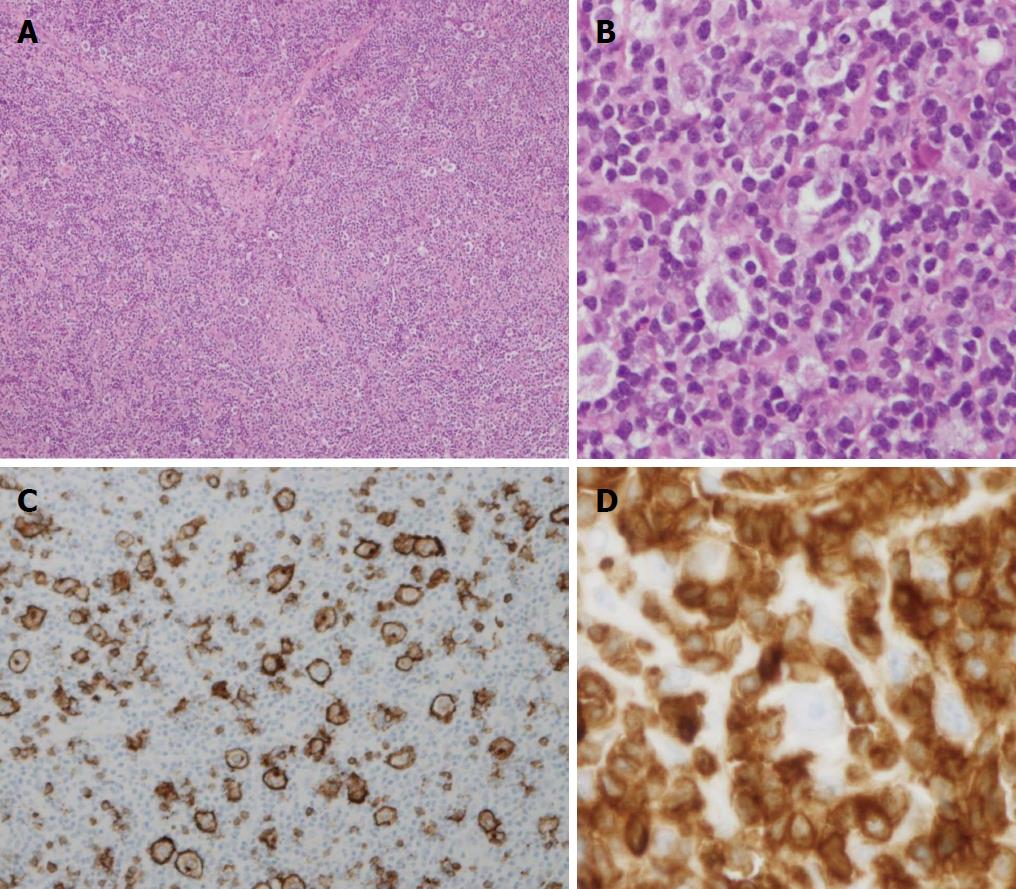

Histologic sections of the lymph node revealed entirely effaced nodal architecture with lymphoid infiltrated and focal sclerosis (Figure 1A). No residual germinal center meshwork was revealed by CD23 stain. There were scattered atypical large lymphoid cells in the background of small reactive lymphocytes and histiocytes. These neoplastic cells were medium to large size with pleomorphic morphologic features. Many of them showed moderate or abundant cytoplasm; some of them showed binucleate or multinucleate with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli that were mimicking “Hodgkin cells” (Figure 1B). A panel of markers was performed as immunohistochemical stains. The neoplastic large cells were positive for CD20 (Figure 1C), CD45, CD79a, PAX5 and EMA. They were negative for CD3, CD15, ALK1, PD-1 and EBER (EBV encoded small RNA by in situ hybridization). These large lymphoma cells were surrounded by CD3+ small T-cell (Figure 1D). CD30 showed nonspecific variable stain on a small subset of lymphoma cells. These pathologic features were consistent with THRBCL. Bone marrow biopsy was shown involvement by THRLBCL.

Initial staging positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) showed hypermetabolic multi compartmental lymphadenopathy above and below the level of the diaphragm, marked splenomegaly compatible with lymphomatous involvement and multiple hypermetabolic bony lesions suspicious for bony involvement. Given the significant disease burden he was given pre-phase cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednisone (COP) and he had an excellent response by PET-CT. Given the bone marrow involvement he was given prophylactic intrathecal therapy with methotrexate alternating with cytarabine. He was treated with a rituximab containing regimen followed by cytarabine, and etoposide maintenance therapy. The patient did well and had resolution of his fevers, headaches, and lymphadenopathies. On follow up PET-CT, the spleen measured 14 cm and there was no evidence of metabolically active disease. His follow up bone marrow biopsy was clear of disease as well.

Lymphadenopathy (LAD) is common in children; often stemming from non-malignant processes[4]. The most common etiology of benign head and neck LAD is usually from infection. They are often focal, acute onset (less than 3 wk), and associated with fever and local signs of infection such as erythema, warmth, and tenderness.

Malignant LAD is far less common. The concerning signs for malignant LAD on physical exam are nontender, firm, immovable lymph nodes usually greater than 2 cm. In addition, systemic symptoms, like weight loss, night sweat, fatigue, and fever, and findings of generalized LAD, supraclavicular LAD, and hepatosplenomegaly raise suspicion for malignancy or lymphoma. Malignant lymphomas are the third most common malignancy in pediatric population (including HL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma or NHL)[5]. In a younger population, NHL is more common. Unlike HL, its incidence increases with age and may occur at any age in childhood with median age of 10 years old. In addition, the incidences of histologic subtypes of NHL vary across the world. In equatorial Africa and northeastern Brazil, Burkitt lymphoma is the predominant histologic subtype of NHL. However, in Japan, Burkitt lymphoma is very rare.

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma is a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) commonly seen in adults in their sixth to seventh decade with a male predilection (male: female ratio of 7:1)[6,7]. Patients with THRLBCL tend to have more advanced-stage disease, B-symptoms, extranodal involvement in contrast to other DLBCL types. Although THRLBCL patients are younger relative to DLBCL, they are uncommon in children[2,3].

We searched PubMed for cases 18 years old or younger with THRLBCL. We found 35 cases (36 cases including this case) reported on literature, with age from 4 to 18 years old, 29 males and 7 females (ratio of 4.1; Table 1[3,8-18]). More than a half of patients were adolescents. Younger children appear more often to have head and neck LAD (Table 1). In cases with known tumor sites, pediatric cases share similar clinical features such as often spleen, liver, and bone marrow involvement as seen in adults; bone marrow infiltrate in 4/15 (26%), as reported 27% in the large adult series[19].

| Case | Ref. | Age (yr) | Gender | Nodal and extranodal locations | BM involvement |

| 1 | Aki et al[8] | 18 | F | Unspecified LN, liver, spleen, pleura | Yes |

| 2 | Gheorghe et al[3] | 15 | M | Axillary, retroperitoneal, hepatic LN, liver, extradural mass (T5) | Yes |

| 3 | Gheorghe et al[3] | 17 | F | Mediastinal, splenic, mesenteric, hepatic LN, liver | No |

| 4 | Kunder et al[9] | 17 | M | Perihepatic | NA |

| 5 | Lones et al[10] | 15 | M | Neck, mediastinal | No |

| 6 | Lones et al[10] | 12 | M | Neck, mediastinal, abdomen, inguinal, spleen, liver | No |

| 7 | Lones et al[10] | 16 | M | Abdomen, inguinal | No |

| 8 | Lones et al[10] | 15 | M | Axillary, inguinal, spleen | No |

| 9 | Lones et al[10] | 16 | M | Neck | No |

| 10 | Lones et al[10] | 16 | M | Axillary | No |

| 11 | Ohgami et al[11] | 16 | M | Periportal | No |

| 12 | Ozgönenel et al[12] | 8 | M | Neck | Yes |

| 13 | Paulli et al[13] | 8 | NA | NA | NA |

| 14 | Petroscu et al[14] | 4.5 | M | Thymus | No |

| 15 | Sathipalan et al[15] | 6 | M | Neck, axillary, peripancreatic, para-aortic, subcarinal, hilar | No |

| 16 | Stenhammer et al[16] | 7 | F | Neck, para-aortic | No |

| 17-32 | Tiemann et al[17] | 8-17 | 13M, 3F | NA | NA |

| 33-35 | Greer et al[18] | 17-18 | 2M, 1F | NA | NA |

| 36 | Wei et al (current case) | 10 | M | Neck, liver, spleen | Yes |

Diagnosis of THRLBCL can be challenging due to its histopathologic features in general. It is characterized as having < 10% neoplastic large B-cells mixed in the background of small reactive T-cells and histiocytes without any large B-cells residing in nodules of small B-cells or in follicular dendritic meshwork, which would indicate nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), a rare subtype of HL. Sometimes, it can be difficult to distinguish THRLBCL from NLPHL[6]. THRLBCL have overlapping features with diffuse NLPHL sharing several identical morphologic and immunophenotypic characteristics. However, latter lack of germinal center meshwork is seen in this case. Although it is still controversial between these two entities, more authors suggest these histopathologic changes seen in these subtypes may represent as a spectrum of same disease. Other lymphomas often share overlapping morphologic features, such cHK, less likely DLBCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, etc. These misclassified cases made up 82% of THRLBCL cases reported in a large series. Overall, the two common mimickers are NLPHL and cHL. All three entities are male predominance. cHL likely presents as limited stage than THRLBCL; NLPHL tend to be younger and rarely present with advanced stage[7,19-21].

THRLBCL is a more aggressive disease with an advanced stage (about two thirds are stage III or IV). It is suggested to treat these patients aggregately with anthracyclin-containing chemotherapy as appropriate for DLBCL at similar clinical stage[2,20]. The 3-year survival rate is estimated to be 50%-64%[20]. However, the pediatric population tend to have a better prognosis upon diagnosis and respond better with therapy compared to adults[3]. Misdiagnosing a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma (one of the treatable childhood cancers with a 5-year survival rate above 98%[22]) and missing THRLBCL would negatively impact patient’s survivability and treatment outcome as the stage of the cancer advances without appropriate treatment.

THRLBCL may be under-recognized in pediatric population[3]. This is due to the high incidence of Hodgkin Lymphoma in pediatric population, and some cases share histological similarity between these two lymphomas. In addition, BM involvement of THRLBCL can be easily missed on aspirate histology alone. Both a high amount of suspicion and immunohistochemistry of any atypical lymphoid infiltrate are needed to make the diagnosis for THRLBCL.

In summary, we describe a case of T-cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma in a child with head and neck lymphadenopathy. Although lymphoma appears much less frequent than reactive LAD, it is still important to consider lymphoma and its subtypes like THRLBCL in the differential. In addition, THRLBCL typically appears more frequently in adults than children. However, that does not rule out this type of lymphoma in the setting of a pediatric patient with lymphoma until proven otherwise by biopsy. A precise diagnosis or classification of THRLBCL will ensure appropriate treatments in these patients. We hope that this case may expand our knowledge and contribute to the review of literature on THRLBCL.

Patient presented to the hospital with 3 mo of persistent intermittent headaches, fevers, nausea/vomiting, cough, swollen neck lymph nodes, and weight loss.

Patient had multilevel neck lymphadenopathy on exam, significant splenomegaly, swelling of lower extremities upon examination, concerned for malignancy.

Neoplastic etiology, such lymphoma and other malignancies were considered in the differential diagnoses.

Complete blood cell count showed anemia.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen revealed significant, small bilateral pleural effusions, splenomegaly of 19 cm and multiple retroperitoneal nodes.

A cervical lymph node biopsy revealed entirely effaced nodal architecture with scattered neoplastic large lymphoid cells in the background of small T-cell and histiocytes, consistent with T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma.

The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednisone (COP), and prophylactic intrathecal therapy with methotrexate alternating with cytarabine.

T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL) is rare in pediatric population. Previous reports have also shown that pediatric patients with THRLBCL may also present with head and neck lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and similar rates of bone marrow involvement compared to adult patients. Pediatric patients tend to have a better prognosis and respond better to therapy compared to adult patients despite there being an overall 3-year survival rate of 50%-64%. Despite knowing pediatric patients do better than adult patients, it is imperative to diagnose THRLBCL as early as possible because prognosis worsens if treatment delayed. Barriers to proper diagnosis of THRLBCL in a pediatric patient are misdiagnosing it as NLPHL and cHL.

HL: Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma; THRLBCL: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma; DLBCL: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; LAD: Lymphadenopathy; NLPHL: Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma; cHL: Classic Hodgkin lymphoma; COP: Cyclophosphamide, oncovin, prednisone; H and E: Hematoxylin and Eosin stain.

THRLBCL should be considered as a differential diagnosis in a pediatric patient presenting with persistent head and neck lymphadenopathy.

| 1. | Ramsay AD, Smith WJ, Isaacson PG. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:433-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chan ACL, Chan JKC. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA; 4: Elsevier; 2017; 433-437. |

| 3. | Gheorghe G, Rangarajan HG, Camitta B, Segura A, Kroft S, Southern JF. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma in pediatric patients: an under-recognized entity? Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2015;45:73-78. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rosenberg TL, Nolder AR. Pediatric cervical lymphadenopathy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kelly KM, Burkhardt B, Bollard CM. Malignant lymphomas in childhood. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017; 1330-1342. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica. 2010;95:352-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hartmann S, Döring C, Jakobus C, Rengstl B, Newrzela S, Tousseyn T, Sagaert X, Ponzoni M, Facchetti F, de Wolf-Peeters C. Nodular lymphocyte predominant hodgkin lymphoma and T cell/histiocyte rich large B cell lymphoma--endpoints of a spectrum of one disease? PLoS One. 2013;8:e78812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aki H, Tuzuner N, Ongoren S, Baslar Z, Soysal T, Ferhanoglu B, Sahinler I, Aydin Y, Ulku B, Aktuglu G. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases and comparison with 43 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2004;28:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kunder C, Cascio MJ, Bakke A, Venkataraman G, O’Malley DP, Ohgami RS. Predominance of CD4+ T Cells in T-Cell/Histiocyte-Rich Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Identification of a Subset of Patients With Peripheral B-Cell Lymphopenia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2017;147:596-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lones MA, Cairo MS, Perkins SL. T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents: a clinicopathologic report of six cases from the Children’s Cancer Group Study CCG-5961. Cancer. 2000;88:2378-2386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ohgami RS, Zhao S, Natkunam Y. Large B-cell lymphomas poor in B cells and rich in PD-1+ T cells can mimic T-cell lymphomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ozgönenel B, Savaşan S, Rabah R, Mohamed AN, Cushing B. Pediatric EBV-positive T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma with clonal cells in the bone marrow without overt involvement. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:465-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Paulli M, Viglio A, Boveri E, Pitino A, Lucioni M, Franco C, Riboni R, Rosso R, Magrini U, Marseglia GL. Nijmegen breakage syndrome-associated T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: case report. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:264-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Petrescu IO, Pleşea IE, Foarfă MC, Bondari S, Singer CE, Dumitrescu EM, Pană RC, Stănescu GL, Ciobanu MO. Rare thymic malignancy of B-cell origin - T-cell÷histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:1075-1083. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sathiapalan RK, Hainau B, Al-Mane K, Belgaumi AF. Favorable response to treatment of a child with T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma presenting with liver failure. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:809-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stenhammar L, Masreliez V. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma in a child with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;17:337-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tiemann M, Riener MO, Claviez A, Meyer U, Dörffel W, Reiter A, Parwaresch R. Proliferation rate and outcome in children with T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study from the NHL-BFM-study group. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1295-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Greer JP, Macon WR, Lamar RE, Wolff SN, Stein RS, Flexner JM, Collins RD, Cousar JB. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas: diagnosis and response to therapy of 44 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1742-1750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | El Weshi A, Akhtar S, Mourad WA, Ajarim D, Abdelsalm M, Khafaga Y, Bazarbashi S, Maghfoor I. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: Clinical presentation, management and prognostic factors: report on 61 patients and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1764-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abramson JS. T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Revised 4th ed. Volume 2. Lyon, France: IARC 2017; 298-299. |

| 22. | Kelly KM. Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents: improving the therapeutic index. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:514-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

CARE Checklist (2013): The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Pathology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Yamamoto S S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW