Published online Dec 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i15.916

Peer-review started: July 24, 2018

First decision: October 8, 2018

Revised: October 14, 2018

Accepted: November 7, 2018

Article in press: November 7, 2018

Published online: December 6, 2018

Processing time: 135 Days and 23.2 Hours

To test the potential association between atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) and migraine in patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure patients through an observational, single-center, case-controlled study.

We studied a total of 450 migraineurs who had right-to-left shunts and underwent PFO closure in a retrospective single-center non-randomized registry from February 2012 to October 2016 on the condition that they were aged 18-45 years old. Migraine was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition and evaluated using the Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6). All patients underwent preoperative transesophageal echocardiography, contrast transthoracic echocardiography, and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging examinations, with subsequent fluoroscopy-guided PFO closure. Based on whether they have ASA or not, the patients were divided into two groups: A (PFO with ASA, n = 80) and B (PFO without ASA, n = 370). Baseline characteristics and procedural and follow-up data were reviewed.

Compared to group B, group A had an increased frequency of ischemic lesions (11.3% vs 6.2%, P = 0.038) and migraine with aura (32.5% vs 21.1%, P = 0.040). The PFO size was significantly larger in group A (P = 0.007). There was no significant difference in HIT-6 scores between the two groups before and at the one-year follow-up after the PFO closure [61 (9) vs 63 (9), P = 0.227; 36 (13) vs 36 (10), P = 0.706].

Despite its small sample size, our study suggests that the prevalence of ASA in PFO with migraine patients is associated with ischemic stroke, larger PFO size, and migraine with aura.

Core tip: The aim of this study was to test the potential association between atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) and migraine in patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure patients. A total of 450 migraineurs who had right-to-left shunts and underwent PFO closure on the condition that they were aged 18-45 years old were observed. Compared to the PFO without ASA patients, the PFO with ASA patients had an increased frequency of ischemic lesions and migraine with aura. The PFO size was significantly larger in PFO with ASA patients. There was no significant difference in Headache Impact Test-6 scores between the two groups before and at the one-year follow-up after the procedure.

- Citation: He L, Cheng GS, Du YJ, Zhang YS. Clinical relevance of atrial septal aneurysm and patent foramen ovale with migraine. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(15): 916-921

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i15/916.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i15.916

Migraine is common, with an estimated prevalence of 8%-12% in the general population (18% of women and 6% of men), and has been acknowledged as one of the most important causes of disability burdens[1]. Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a remnant of the fetal anatomy with a slit-like interatrial opening that is present in approximately 27% of the general population[2]. Although not all migraineurs have a PFO, and not all PFO patients have migraine, interestingly, PFO is more prevalent in migraineurs (approximately 48% in migraineurs with aura, 23% in in migraineurs without aura, and only 20% in controls)[3]. The pathophysiological mechanisms between PFO and migraine remain entirely unknown. Anecdotally, the closure of a PFO for nonmigraine indications has been shown to ameliorate pre-existing migraine in numerous retrospective series published after 2000[4-8]. Therefore, the hypothesis of the right-to-left shunts (RLS) of chemical or physical triggers for migraine has been proposed.

Atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) is redundant septal primum tissue with excessive mobility of the fossa ovalis. The prevalence of ASA is approximately 2%-3% in the general population. An ASA increases the likelihood of the presence of a PFO, whereas the incidence of ASA in PFO patients is significantly higher than that of the general population[9]. With the continuous deeper study of PFO, ASA has been identified as an independent risk factor for cryptogenic stroke in PFO patients[10,11]. Patients with migraine appear to be at risk for silent stroke, which might be related to the presence of a PFO. However, the association of ASA and migraine in PFO patients remains unknown.

In a retrospective single-center non-randomized registry from February 2012 to October 2016, we enrolled 450 patients diagnosed with migraine who had RLS and underwent transcatheter PFO closure at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University on the condition that they were aged 18-45 years old. All patients underwent preoperative contrast transthoracic echocardiography (cTTE), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations, with subsequent fluoroscopy-guided PFO closure. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition, migraine was diagnosed by two neurologists[12], and evaluated by Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) scores.

The patients gave their informed written consent to the procedures. The local ethics committee approved this study. Based on whether they had an ASA or not, the patients were divided into two groups: A (PFO with ASA, n = 80) and B (PFO without ASA, n = 370). Baseline characteristics and procedural and follow-up data were reviewed.

All patients had a diagnostic cTTE and TEE study performed prior to the procedure. An ultrasound system with a 2-4 MHz transducer was used to perform cTTE and a 4-7 MHz transducer was used to perform TEE. As reported by Agmon et al[9], an ASA was defined if the excursion of the septum primum into the left/right atriums exceeded 10 mm or the total excursion distance was more than 15 mm. The apical four-chamber view was generally selected when performing cTTE. The presence of RLS was identified when micro-bubbles were seen in the left atrium within the first three cardiac cycles after contrast appearance in the right atrium during normal respiration or the Valsalva maneuver. The severity of the RLS was semi-quantified into a four-level scale[13].

The procedure was performed under 2% lidocaine local anesthesia. All the operations were performed by the same interventional cardiologist and first assistant. The right femoral vein was accessed and intravenous heparin (80-100 IU/kg) was administered. The device implantation was guided only by fluoroscopy. The device size was determined according to the surgeon’s preference. The Amplatzer PFO occluder (St. Jude Medical, Golden Valley, MN, United States) and the Cardi-O-Fix PFO occluder (Starway Medical Technology Inc., Beijing) were used during the study period. The occluder type included 18/18 mm, 18/25 mm, 30/30 mm, and 25/35 mm.

After the procedure, low-molecular-weight heparin (10 U/kg·h) was administered for 48 h. Aspirin 100 mg/d for 6 mo and clopidogrel 50-75 mg/d for 3 mo were administered to all patients following device implantation. All patients were followed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo post-procedure and yearly thereafter. The HIT-6 score was recorded to evaluate the severity of migraine. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed to confirm early residual shunting and device embolization within 24 h following the procedure. cTTE was performed at 3 mo after the procedure to observe residual RLS. If there was no residual RLS, cTTE was not required in future follow-up examinations. If the RLS remained, cTTE was performed at 180-d follow-up after the procedure. All patients were followed after device implantation through questionnaires made by phone calls or office visits. For patients with symptoms of palpitation, Holter monitoring was performed to confirm the presence or absence of atrial fibrillation. Follow-up was completed in Oct 2017.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 24.0, for Windows, SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Summary statistics for normally distributed quantitative variables are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences in means for continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test. For non-normally distributed variables, we used the median and interquartile range (IQR). Differences in medians for non-normally distributed variables were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are summarized as ratios and percentages. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used for two-group comparisons. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 450 participants (group A: PFO with ASA, n = 80; group B: PFO without ASA, n = 370) were included in the study. The baseline characteristics of the two groups are listed in Table 1. There were no significant differences regarding age, weight, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, history of smoking, or baseline HIT-6 scores between the two groups (P > 0.05).

| Group A (n = 80) | Group B (n = 370) | Sig (P) | |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 34 (12) | 34 (13) | 0.968 |

| Weight, kg, median (IQR) | 60 (13) | 59 (15) | 0.549 |

| Women | 62 (77.5) | 259 (70) | 0.227 |

| Hypertension | 4 (5.0) | 11 (3.0) | 0.567 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (1.25) | 2 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (6.3) | 31 (8.4) | 0.683 |

| History of smoking | 14 (17.5) | 82 (22.2) | 0.440 |

| Ischemic lesions detected by CT/MRI | 11 (11.3) | 23 (6.2) | 0.038 |

| Migraine with aura | 26 (32.5) | 78 (21.1) | 0.040 |

Compared with group B, group A exhibited an increased frequency of ischemic brain lesions, as observed with MRI/CT (11.3% vs 6.2%, P = 0.038). Migraine with aura was found to be more prevalent in group A (32.5% vs 21.1%, P = 0.040). The PFO size ranged from 1.0-9.3 mm (median 2.6 mm) in group A and 0.7-9.3 mm (median 2.1 mm) in group B. The PFO size was significantly larger in patients with ASA compared those without (P = 0.007).

The Amplatzer PFO occluder was used in 146 patients (32.4%), and the Cardi-O-Fix PFO occluder was used in 304 patients (67.6%). Technical success was defined as the delivery and release of the device and was achieved in all patients. Procedural success, defined as implantation without in-hospital serious adverse events, was also achieved in all patients. Procedural complications included two arteriovenous fistulae, two false aneurysms, and one inguinal hematoma. There were no procedure-related deaths, strokes, or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

The mean follow-up period was 3 (2) years. Residual RLS was detected by cTTE in two (2.5%) cases 180 days after the procedure in group A, while there was no residual RLS detected by cTTE 180 days after the procedure in group B. No patients experienced TIAs or stroke after the procedure. Two (0.44%) cases of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation occurred (at 2 wk and 3 mo after the procedure). One reverted spontaneously to a sinus rhythm, and the other underwent pharmacological conversion to a sinus rhythm. No cases of occluder translocation, occlude erosion, pericardial effusion, or puncture site bleeding was found in our study.

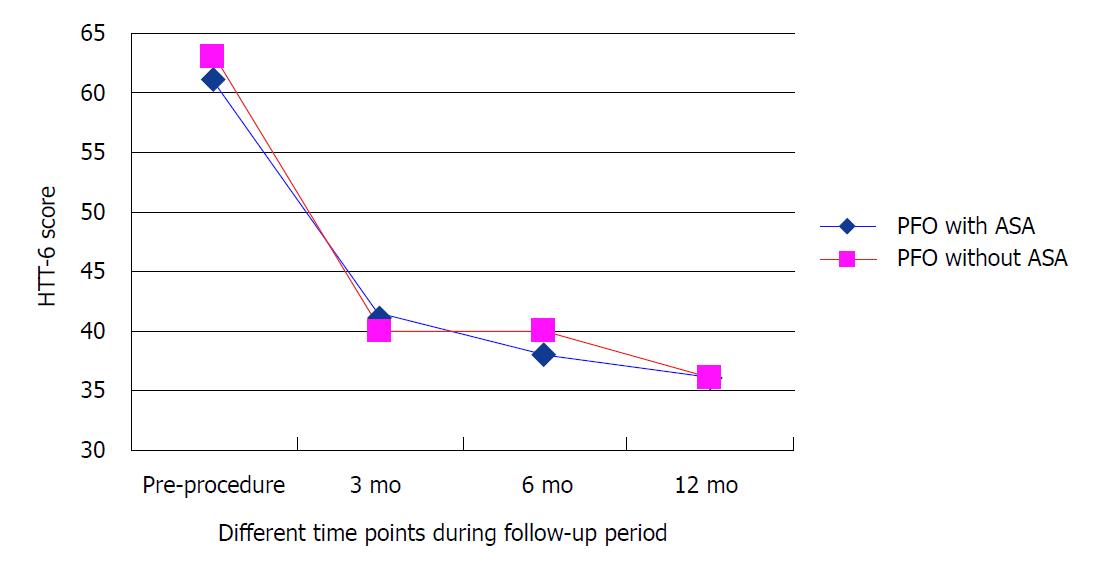

We compared HIT-6 scores at different time points during the follow-up period after the procedure. At 3 mo after closure, the average HIT-6 scores were 41 (15) in group A and 40 (15) in group B. At 6 mo after closure, the average HIT-6 scores were 38 (11) in group A and 40 (10) in group B. At 12 mo after closure, the average HIT-6 scores were 36 (13) in group A and 36 (10) in group B; the average HIT-6 scores at baseline were 61 (9) and 63 (9) for group A and group B, respectively (Figure 1). At the one-year follow-up after the PFO closure, there was no significant difference in HIT-6 scores between the two groups (P = 0.706).

Since 1998, when Del Sette et al[14] found that 41% of a migraine group and 16% of a control group had PFO-RLS, the relationship between migraine and PFO has been extensively studied. Unfortunately, the current literature remains discordant as to whether a link exists between PFO and migraine. Some observational studies have shown that PFO and migraine are closely related. For most migraine patients with a PFO, migraine can be greatly alleviated after PFO closure[15,16]. However, other studies found no association between migraine and the presence of a PFO[17,18].

The reasons for the inconsistent results of the above research might be explained in different ways. First, many observational studies include different types of migraine populations, mainly cryptogenic stroke patients with migraine, while other studies with the opposite opinion mostly exclude these patients with pathological PFO[19]. Second, one of the factors that is most strongly associated with the occurrence of a cryptogenic stroke is the presence of a combination of a PFO with an ASA, and the incidence of migraine in these patients is also significantly higher[20,21]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the link between a PFO and migraine might be an ASA.

The main findings of our study suggest that the prevalence of ASA and migraine in PFO patients is associated with silent stroke, severe RLS, and migraine with aura. The incidence of ASA in the normal population is 1%-2.2%[22] when determined by autopsy and 1%-4.9% when determined by TEE[23].The incidence of ASA in cryptogenic stroke and TIAs is approximately 7.9%, which is significantly higher than that of the general population[9]. In 50%-89% of patients with an ASA, a PFO is also seen, and the PFO size is also larger when accompanied by an ASA[9]. The association between ASA and PFO has emerged as a factor that can potentially increase the risk of stroke occurrence or relapse. Because of the unknown mechanisms of migraine itself, the pathogenesis of silent stroke in migraine patients is also in the hypothesis stage. Previous studies showed that the possibility of stroke was significantly increased in patients with PFO combined with ASA, while a paradoxical embolism was considered to be the main mechanism of stroke. Overell et al[11] found that the risk of stroke was 4.96 times higher in patients with PFO with ASA compared with the normal population. Compared with the control group, the odds ratio for stroke was 6.14 in patients younger than 55 years old; and in patients with a simple PFO, the odds ratio for stroke was 3.10; if patients had a PFO with an ASA, the odds ratio for stroke was as high as 15.59. A prospective cohort study by Mas et al[24] found that the possibility of recurrent stroke or TIAs in simple PFO patients was 6% under 300 mg/d aspirin condition; if an ASA was combined with a PFO, the incidence increased to 15.6%. After 4 years of follow-up, the relative risk of recurrent stroke or TIA was 5.6 in simple PFO patients and 19.2 in PFO with ASA patients. Therefore, an ASA can increase the possibility of paradoxical embolisms in PFO patients. When a PFO is combined with ASA, the presence of an ASA can lead to increased PFO channel opening frequency and a wider opening. In addition, the presence of an ASA can change the direction of blood flow, allowing the blood flow of the inferior vena cava into the PFO and promoting a RLS, thus resulting in cerebral ischemic events[25]. In this study, the prevalence of silent infarct-like lesions in patients with migraine and an ASA was higher, which is also consistent with previous study results.

In the current study, we found that patients with an ASA had a larger PFO than those without an ASA. The grade of the RLS in patients with an ASA was also larger than that of patients without an ASA. The size of the PFO directly correlated with the degree of the shunt. Larger PFO sizes allowed a higher number of microbubbles to enter systemic circulation. Larger shunts might also increase the likelihood of paradoxical embolization to the brain and, hence, explain the statistically increased stroke risk associated with migraine[20].

Our study also found that the incidence of migraine with aura was higher in people with an ASA. Wilmshurst et al[26] studied the incidence of migraine in 200 divers with decompression sickness. The results showed that the prevalence of migraine was higher in patients with a larger RLS (especially in those who showed a persistent RLS at rest). A large RLS may induce migraine, especially migraine with aura. Anzola et al[27] studied 420 cases of RLS and found that the degree of the RLS could predict the occurrence of migraine and that the degree of the RLS in migraine patients was larger than that of non-migraine patients.

Moreover, a recent study by Snijder et al[28] also confirmed this finding. A plausible hypothesis for mrgraine is that, via the PFO, a venous to arterial passage of activated platelets or chemical substances may trigger a headache by overwhelming the filtering capacity of the lungs[29]. Therefore, the size of the PFO and the degree of the RLS through it may be the major determinants for whether a PFO acts as a conduit for paradoxical embolization. By comparing migraine relief after PFO closure at different time points during the follow-up period in patients with or without an ASA, we found similar mean HIT-6 scores at 3, 6, and 12 mo after the procedure, which were all significantly decreased in comparison with the baseline values. However, regardless of whether patients had an ASA or not, there were no significant differences between the two groups. From the above information, we speculated that the PFO closure effects likely affected early judgments about headache relief. In our study, the incidence of a residual RLS was very low in both groups, which was associated with an accurate preoperative TEE examination. We speculate that the low incidence of residual shunts after the operation relieved migraine attacks and significantly reduced the HIT-6 scores.

This single-center, case-controlled study cohort, despite its small sample size, suggests that the prevalence of ASA with migraine in PFO patients is associated with ischemic stroke, larger PFO size, and migraine with aura.

The relationship between patent foramen ovale (PFO) with atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) and migraine remains controversial. We examined this association through an observational, single-center, case-controlled study.

A PFO with ASA has been identified as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Patients with migraine with aura appear to be at risk for silent brain infarction, which might be related to the presence of a PFO. However, the association between ASA and migraine in PFO closure patients has rarely been reported. Therefore, in addition to clarifying the relationship between PFO, ASA, and migraine, this study also hopes to provide guidance for the choice of migraine patients who can benefit more from PFO closure.

The research objective of this study was to test the potential association between ASA and migraine in PFO closure patients. Because ASA is a structural abnormality, our findings also verify the role of ASA in migraine with PFO patients. Further PFO and migraine studies should focus on the specific intra-atrial structural abnormality.

We retrospectively analyzed 450 migraineurs who had right-to-left shunts and underwent PFO closure from February 2012 to October 2016. The patients were classified into two groups according to whether they had ASA or not: the PFO with ASA group and the PFO without ASA group. This study is a single-center, non-randomized, case-controlled study.

Our research found that the PFO with ASA patients had an increased frequency of ischemic lesions and migraine with aura. The PFO size was significantly larger in PFO with ASA patients. However, there was no significant difference in Headache Impact Test-6 scores between the PFO with ASA and without ASA groups before and after the PFO closure. Given its nature, the present study shares all of the limitations of case-controlled studies. In our study, the mean follow-up time was only 1 years. Although the effect of PFO closure on migraine usually appears within this time frame, the results may have been affected. The small sample size is another limitation of this study.

This single-center, case-controlled study cohort, despite its small sample size, suggests that the prevalence of ASA with migraine in PFO patients is associated with ischemic stroke, larger patent foramen ovale size, and migraine with aura. That is to say, the presence/absence of an ASA is associated with differences in baseline characteristics but not with differences in severity of migraine as demonstrated by the similar score results.

We used the anatomical abnormality of ASA as a breakthrough point, and concluded that patients with ASA have a large PFO diameter and a high incidence of ischemic stroke and migraine with aura. According to our experience, the direction of the future research should focus on the anatomical abnormality of PFO. And we also believe that the highest level of evidence in clinical studies is still a multi-center, prospective, randomized controlled study.

| 1. | Lipton RB, Liberman JN, Kolodner KB, Bigal ME, Dowson A, Stewart WF. Migraine headache disability and health-related quality-of-life: a population-based case-control study from England. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:441-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:17-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1669] [Cited by in RCA: 1605] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Anzola GP, Magoni M, Guindani M, Rozzini L, Dalla Volta G. Potential source of cerebral embolism in migraine with aura: a transcranial Doppler study. Neurology. 1999;52:1622-1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wilmshurst PT, Nightingale S, Walsh KP, Morrison WL. Effect on migraine of closure of cardiac right-to-left shunts to prevent recurrence of decompression illness or stroke or for haemodynamic reasons. Lancet. 2000;356:1648-1651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khessali H, Mojadidi MK, Gevorgyan R, Levinson R, Tobis J. The effect of patent foramen ovale closure on visual aura without headache or typical aura with migraine headache. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:682-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morandi E, Anzola GP, Angeli S, Melzi G, Onorato E. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale: a new migraine treatment? J Interv Cardiol. 2003;16:39-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anzola GP, Frisoni GB, Morandi E, Casilli F, Onorato E. Shunt-associated migraine responds favorably to atrial septal repair: a case-control study. Stroke. 2006;37:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wahl A, Praz F, Tai T, Findling O, Walpoth N, Nedeltchev K, Schwerzmann M, Windecker S, Mattle HP, Meier B. Improvement of migraine headaches after percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale for secondary prevention of paradoxical embolism. Heart. 2010;96:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, Gentile F, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, O’Fallon WM, Covalt JL, Wiebers DO, Seward JB. Frequency of atrial septal aneurysms in patients with cerebral ischemic events. Circulation. 1999;99:1942-1944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Handke M, Harloff A, Olschewski M, Hetzel A, Geibel A. Patent foramen ovale and cryptogenic stroke in older patients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2262-2268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Overell JR, Bone I, Lees KR. Interatrial septal abnormalities and stroke: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Neurology. 2000;55:1172-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6960] [Cited by in RCA: 6510] [Article Influence: 813.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhao E, Wei Y, Zhang Y, Zhai N, Zhao P, Liu B. A Comparison of Transthroracic Echocardiograpy and Transcranial Doppler With Contrast Agent for Detection of Patent Foramen Ovale With or Without the Valsalva Maneuver. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Del Sette M, Angeli S, Leandri M, Ferriero G, Bruzzone GL, Finocchi C, Gandolfo C. Migraine with aura and right-to-left shunt on transcranial Doppler: a case-control study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1998;8:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reisman M, Christofferson RD, Jesurum J, Olsen JV, Spencer MP, Krabill KA, Diehl L, Aurora S, Gray WA. Migraine headache relief after transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:493-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rigatelli G, Dell’avvocata F, Cardaioli P, Giordan M, Braggion G, Aggio S, L’erario R, Chinaglia M. Improving migraine by means of primary transcatheter patent foramen ovale closure: long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;2:89-95. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Rundek T, Elkind MS, Di Tullio MR, Carrera E, Jin Z, Sacco RL, Homma S. Patent foramen ovale and migraine: a cross-sectional study from the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS). Circulation. 2008;118:1419-1424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garg P, Servoss SJ, Wu JC, Bajwa ZH, Selim MH, Dineen A, Kuntz RE, Cook EF, Mauri L. Lack of association between migraine headache and patent foramen ovale: results of a case-control study. Circulation. 2010;121:1406-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tobis J. Management of patients with refractory migraine and PFO: Is MIST I relevant? Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Etminan M, Takkouche B, Isorna FC, Samii A. Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2005;330:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, Bakkers JT, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. JAMA. 2004;291:427-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 686] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Silver MD, Dorsey JS. Aneurysms of the septum primum in adults. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1978;102:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Pearson AC, Nagelhout D, Castello R, Gomez CR, Labovitz AJ. Atrial septal aneurysm and stroke: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:1223-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mas JL, Arquizan C, Lamy C, Zuber M, Cabanes L, Derumeaux G, Coste J; Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Aneurysm Study Group. Recurrent cerebrovascular events associated with patent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm, or both. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1740-1746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 969] [Cited by in RCA: 883] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hanna JP, Sun JP, Furlan AJ, Stewart WJ, Sila CA, Tan M. Patent foramen ovale and brain infarct. Echocardiographic predictors, recurrence, and prevention. Stroke. 1994;25:782-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wilmshurst P, Pearson M, Nightingale S. Re-evaluation of the relationship between migraine and persistent foramen ovale and other right-to-left shunts. Clin Sci (Lond). 2005;108:365-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Anzola GP, Morandi E, Casilli F, Onorato E. Different degrees of right-to-left shunting predict migraine and stroke: data from 420 patients. Neurology. 2006;66:765-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Snijder RJ, Luermans JG, de Heij AH, Thijs V, Schonewille WJ, Van De Bruaene A, Swaans MJ, Budts WI, Post MC. Patent Foramen Ovale With Atrial Septal Aneurysm Is Strongly Associated With Migraine With Aura: A Large Observational Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:pii: e003771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Beda RD, Gill EA Jr. Patent foramen ovale: does it play a role in the pathophysiology of migraine headache? Cardiol Clin. 2005;23:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

STROBE Statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dai HL, Hochholzer W, Karatza AA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Song H