Published online Jun 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i6.146

Peer-review started: January 19, 2016

First decision: February 26, 2016

Revised: March 23, 2016

Accepted: April 20, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

Published online: June 16, 2016

Processing time: 135 Days and 21.1 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD) can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to anus. However, gastroduodenal CD is rare with a frequency reported to range between 0.5% and 4.0%. Most patients with gastroduodenal CD have concomitant lesions in the terminal ileum or colon, but isolated gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease is an extremely rare presentation of the disease accounting for less than 0.07% of all patients with CD. The symptoms of gastroduodenal CD include epigastric pain, dyspepsia, early satiety, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. The diagnosis of gastroduodenal CD requires a high level of clinical suspicion and can be made by comprehensive clinical evaluation. Here we report a rare case of isolated duodenal CD not confirmed by identification of granuloma on biopsy, but diagnosed by clinical evaluation.

Core tip: Most gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease (CD) is associated with involvement of the terminal ileum and colon. CD confined to the stomach or duodenum may occur very rarely. Upper CD is typically confirmed by the presence of granulomas on biopsy, but endoscopic biopsies often fail to reveal granulomas. Thus, diagnosis of gastroduodenal CD requires a high level of clinical suspicion and can be made by comprehensive clinical evaluation if there are no definite histologic findings. This rare case highlights the importance of clinical suspicion and comprehensive clinical evaluation for the diagnosis of isolated gastroduodenal CD.

- Citation: Song DJ, Whang IS, Choi HW, Jeong CY, Jung SH. Crohn's disease confined to the duodenum: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(6): 146-150

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i6/146.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i6.146

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disease with transmural involvement of any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to anus[1]. Although CD can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, it is most often associated with involvement of the terminal ileum or colon and may rarely affect the stomach and duodenum[2]. CD confined to the stomach or duodenum without involvement of the small intestine and colon is very rare[1,2].

The first report of duodenal involvement of CD was described by Gottlieb and Alpert in 1937, and Ross reported gastric CD for the first time in 1949[3-5]. Gastroduodenal CD may present with symptoms of epigastric pain, dyspepsia, early satiety, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss[6,7]. There is no gold standard criteria for the diagnosis of CD, which is usually made by comprehensive clinical evaluation and there are no definitive guidelines for management of CD[8,9].

We encountered a case of a 33-year-old woman with isolated duodenal CD presenting with epigastric soreness and dyspepsia without evidence of involvement of the ileum or colon. Here we describe the details of this case with a review of the literature.

A previously healthy 33-year-old woman visited our outpatient department with epigastric soreness and dyspepsia lasting one month. These symptoms were constant and not associated with meals. There were no provoking or palliating factors for these symptoms. Her medical and surgical history was unremarkable as was her family history. She had never undergone endoscopy nor did she take any medicines. She did not drink alcohol or smoke.

In the outpatient clinic her blood pressure was 117/60 mmHg, pulse 76/min, respiratory rate 20/min and body temperature 36.7 °C. Physical examination revealed normal bowel sounds, a soft, flat abdomen, and no epigastric tenderness. Initial laboratory tests were normal (Table 1). Chest X-ray was unremarkable.

| Reference value | ||

| WBC (/μL) | 4160 | 4 × 103-10 × 103 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.7 | 12-16 |

| Hct (%) | 40.8 | 37-47 |

| RBC (/μL) | 4.21 | 4.2 × 106-5.4 × 106 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0-0.5 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 96 | 74-100 |

| TP/Alb (g/dL) | 6.7/4.1 | 6-8/3.3-5.3 |

| AST/ALT (IU/L) | 25/21 | 0-40/0-40 |

| ALP/γ-GTP (IU/L) | 44/8 | 39-117/0-58 |

| TB/DB (mg/dL) | 0.8/0.2 | 0.2-1.2/0-0.6 |

| BUN/Cr (mg/dL) | 9.1/0.62 | 5-25/0.5-1.4 |

| TC (mg/dL) | 160 | 150-250 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 55 | 44-166 |

| U/A | No remarkable findings | |

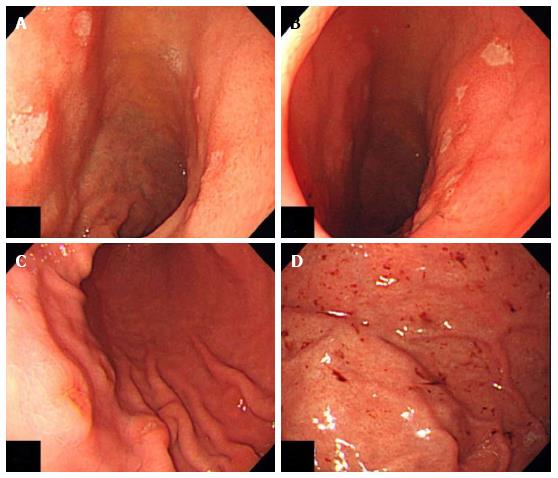

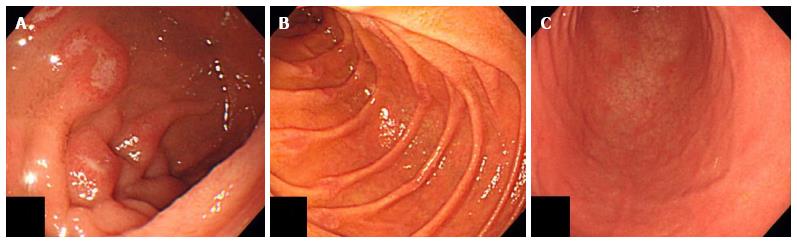

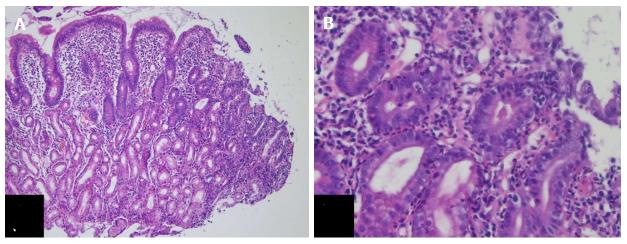

Subsequently, she underwent esophago gastroduo denoscopy (EGD), which revealed multiple early stage ulcers in the bulb of the duodenum and acute to healing stage erosions on the great curvature side of the lower body and hemorrhagic spots in the fundus of stomach (Figure 1). The Campylobacter-like organism test was negative. She took a proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 40 mg) orally for two weeks at home, but visited our outpatient department again as her epigastric soreness and dyspepsia had not improved. She was instructed to take the proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 20 mg) for an additional four weeks. Despite taking pantoprazole for a total of six weeks, her symptoms did not improve at all. She underwent a repeat EGD with biopsy, which showed multiple progressive ulcers and erosions with surrounding mucosal edematous changes in the bulb and the second portion of the duodenum (Figure 2). The gastric lesions had disappeared completely (Figure 2). Biopsies from the ulcerative lesion in the duodenal bulb indicated erosion and infiltration of inflammatory cells, which were primarily plasma cells (Figure 3). The entire colon and terminal ileum were unremarkable on colonoscopy.

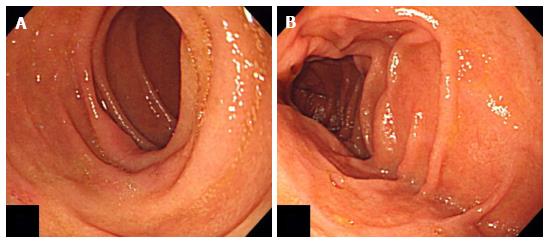

Although endoscopic biopsies failed to reveal granulomas, the unresponsiveness of her duodenal ulcers to pantoprazole and the nonspecific inflammatory changes observed on biopsies from the duodenal bulb were thought to be compatible with duodenal CD. Thus, she was started on 20 mg of prednisolone for two weeks, 10 mg of prednisolone for one week, and 5 mg of prednisolone for one week orally at home. The patient did not complain of any gastrointestinal symptoms at her follow-up visit four weeks later. She underwent a follow-up EGD after completing her four-week course of oral prednisolone. The EGD showed multiple nearly healed ulcers and erosions in the bulb and second portion of the duodenum (Figure 4). With respect to the patient’s response to corticosteroid treatment, duodenal CD is more likely suggested. She continues to see us in follow-up.

CD is almost always found in the small intestine and colon[1,2]. CD may rarely affect the stomach and duodenum, and the frequency of gastroduodenal CD is reported to range between 0.5% and 4.0% in all patients with CD[1,2,10]. Most patients with gastroduodenal CD have concomitant lesions in the terminal ileum or colon[3,11]. CD confined to the duodenum or stomach without involvement of the small intestine or colon is very rare and occurs in less than 0.07% of all patients with CD[1].

The incidence and prevalence of CD in East Asia is lower than in Western countries, but are on the rise[12]. There have been no large epidemiologic studies conducted on a nationwide scale to examine CD in South Korea, but it is possible to estimate the epidemiologic pattern of CD in South Korea from a 20-year population-based epidemiologic study of CD in the Songpa-Gangdong district of Seoul. This study showed that the incidence of CD was 0.05 cases per 100000 person-years in 1986-1990 and rose to 1.34 cases per 100000 person-years in 2001-2005[13]. The adjusted prevalence of CD per 100000 persons on December 31, 2005 was 11.24 cases. That study also indicated that the incidence and prevalence of CD in Seoul, South Korea are still lower than those in Western countries, but rapidly increasing in recent years. There have been no epidemiologic studies on patients with upper gastrointestinal CD in South Korea.

Many patients with gastroduodenal CD are asymptomatic[1,2,7]. The most common symptom is epigastric pain, which is often postprandial, does not radiate, and usually relieved by foods and antacids[1,2]. Other common symptoms include dyspepsia, early satiety, nausea with or without vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss[6,7]. Although hematemesis and melena may rarely occur, upper gastrointestinal bleeding may manifest in the form of chronic anemia[2].

The diagnosis of gastroduodenal CD requires a high level of clinical suspicion[2]. The endoscopic findings of gastroduodenal CD are patchy erythematous granular mucosa, multifocal erythematous spots, friability and various degrees of ulceration of the stomach and irregular thickened duodenal folds, a cobblestone-like appearance, polypoid lesions and focal ulceration of the duodenum[6,14]. Identification of granulomas on biopsy is the most important step in confirming upper CD, but endoscopic biopsies often fail to reveal granulomas because tissues from these biopsies are usually confined to the mucosa[3,15]. Granulomas are more often distributed in the submucosa, subserosa, intermuscular septa and regional lymph nodes than in the mucosa[3,15]. For this reason, granulomas are found on endoscopic biopsies only between 0% and 83% of the time, and focally distributed nonspecific inflammation is a more common finding on histology[6,10]. Thus, if there are no definite histologic findings, gastroduodenal CD can still be diagnosed by comprehensive clinical evaluation including detailed history taking, physical examination, radiologic findings, endoscopic evaluation, and histologic and laboratory investigations[8].

Because there is no definitive cure for CD, many management decisions are made depending on the clinical experience of the treating physician(s)[9]. The treatment of gastroduodenal CD is similar to that of more distal CD with the addition of a proton pump inhibitor[1,10]. The first line of the treatment in active gastroduodenal CD is a proton pump inhibitor in combination with steroids[1]. Generally, duodenal CD is initially managed with medical treatment and good results are achieved with corticosteroid therapy[10,16]. However, surgical intervention is required when medical treatment fails or there are complications such as gastric outlet obstruction, bleeding, perforation and fistula formation[10,16].

The prognosis of gastroduodenal CD is usually good whether treated medically or surgically[2,10,16,17], but a number of complications may arise. The most common complication of gastroduodenal CD is gastric outlet obstruction due to stricture formation, which should be considered when there is prominent and continuous abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting[2,10,16,17]. Gastroduodenal fistulas are relatively rare and almost always result from adjacent diseased colon or terminal ileum connecting to the stomach or duodenum[10,16]. In contrast to peptic ulcer disease, perforation and severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage are seldom detected[2,17]. Duodenal CD can also be the cause of chronic or acute pancreatitis[3,8,11]. Pancreatitis in duodenal CD is rare and may be related to reflux of duodenal contents into the pancreatic duct or to stenosis or obstruction of the ampulla of Vater from duodenal inflammation[2,6]. Very rarely, long-standing upper gastrointestinal CD is complicated by malignant degeneration[6,18-20].

Isolated gastroduodenal CD occurs very rarely and can be diagnosed by comprehensive clinical evaluation with a high level of clinical suspicion if there are no confirmative histologic findings. Gastroduodenal CD should also be considered when gastroduodenal ulcers do not respond to antiulcer drugs such as proton pump inhibitors in young patients.

A previously healthy 33-year-old woman with epigastric soreness and dyspepsia lasting one month.

Crohn’s disease (CD) confined to the duodenum without involvement of the small intestine and colon.

Peptic ulcer disease.

The patient’s data were normal in initial laboratory tests.

Despite six weeks of pantoprazole treatment, multiple progressive ulcers and erosions with surrounding mucosal edematous changes in the bulb and the second portion of the duodenum were observed on repeated upper endoscopy.

Biopsies from the ulcerative lesion in the duodenal bulb indicated erosion and infiltration of inflammatory cells, primarily plasma cells.

The patient was given an oral treatment of 20 mg of prednisolone for two weeks, 10 mg of prednisolone for one week, and 5 mg of prednisolone for one week to take at home.

Diagnosis of CD can be made by a comprehensive clinical evaluation if there are no definite histologic findings.

Gastroduodenal CD refers to CD found in the stomach or duodenum.

Isolated duodenal CD is rare and requires a high level of clinical suspicion for an accurate diagnosis.

This article describes a rare case of CD isolated to the duodenum that was diagnosed by careful clinical evaluation.

| 1. | Ingle SB, Adgaonkar BD, Jamadar NP, Siddiqui S, Hinge CR. Crohn’s disease with gastroduodenal involvement: Diagnostic approach. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:479-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kefalas CH. Gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16:147-151. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hwang YY, Jo YK, Cha JM, Kim KH, Na IH, Lee DH, Ha HS, Kim SH, and Song CS. A Case of Crohn’s Disease Confined to the Stomach. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;26:146-149. |

| 4. | Kwon SW, Lee JH, Park YN, Chi HS. Isolated duodenal Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg Treat Res. 1999;56:602-607. |

| 5. | Gottlieb C, Alpert S. Regional jejunitis. Am J Roentgenol. 1937;38:881-883. |

| 6. | van Hogezand RA, Witte AM, Veenendaal RA, Wagtmans MJ, Lamers CB. Proximal Crohn’s disease: review of the clinicopathologic features and therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:328-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loftus EV Jr. Upper gastrointestinal tract Crohn’s disease. Clin Perspect Gastroenterol. 2002;5:188-191. |

| 8. | Ye BD, Jang BI, Jeen YT, Lee KM, Kim JS, Yang SK. [Diagnostic guideline of Crohn’s disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:161-176. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ye BD, Yang SK, Shin SJ, Lee KM, Jang BI, Cheon JH, Choi CH, Kim YH, Lee H. [Guidelines for the management of Crohn’s disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:141-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Isaacs KL. Upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:451-462, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wagtmans MJ, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB, van Hogezand RA. Clinical aspects of Crohn’s disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comparison with distal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1467-1471. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lee JW, Im JP, Cheon JH, Kim YS, Kim JS, Han DS. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Studies in Korea: Present and Future. Intest Res. 2015;13:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lenaerts C, Roy CC, Vaillancourt M, Weber AM, Morin CL, Seidman E. High incidence of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement in children with Crohn disease. Pediatrics. 1989;83:777-781. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Korelitz BI, Waye JD, Kreuning J, Sommers SC, Fein HD, Beeber J, Gelberg BJ. Crohn’s disease in endoscopic biopsies of the gastric antrum and duodenum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;76:103-109. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. An audit of gastroduodenal Crohn disease: clinicopathologic features and management. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nugent FW, Roy MA. Duodenal Crohn’s disease: an analysis of 89 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:249-254. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hawker PC, Gyde SN, Thompson H, Allan RN. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine complicating Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1982;23:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Meiselman MS, Ghahremani GG, Kaufman MW. Crohn’s disease of the duodenum complicated by adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Radiol. 1987;12:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Slezak P, Rubio C, Blomqvist L, Nakano H, Befrits R. Duodenal adenocarcinoma in Crohn’s disease of the small bowel: a case report. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:15-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Korelitz BI, Riss S, Slomiany BL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ