Published online Mar 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i3.94

Peer-review started: June 10, 2015

First decision: August 15, 2015

Revised: October 14, 2015

Accepted: November 13, 2015

Article in press: November 17, 2015

Published online: March 16, 2016

Processing time: 280 Days and 19.5 Hours

Chronic hepatitis caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an endemic disease in India. It is associated with extrahepatic manifestations like polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) which is a vasculitis like disorder, presenting in subacute or chronic phase; involving visceral and systemic vessels. It should always be considered as a possible etiology of hypertension in an underlying setting of hepatitis B. We describe a 56-year-male patient with a history of chronic HBV who presented to the outpatient clinic with history of recent onset hypertension and suspected liver disease. Further work up for the cause of recent hypertension included a contrast computerized tomography of abdomen, which revealed concomitant pathologies of chronic liver disease and multiple aneurysms in bilateral kidneys. This case illustrates the unusual presentation of extrahepatic manifestation of viral hepatitis in the form of PAN of kidneys. PAN as an independent entity may be missed in specialized clinics evaluating liver pathologies, due to its insidious onset, atypical clinical symptoms and multi-systemic manifestations. The knowledge of extrahepatic, renal and vascular manifestations of hepatitis B unrelated to liver disease should be considered by physicians at the time of diagnosis and management of patients with HBV.

Core tip: Extra hepatic manifestation of viral hepatitis B infection may be its first presenting symptom. This unusual presentation may be in the form of hypertension in a middle aged patient which is usually a part of vasculitis like disease process such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). PAN as an independent entity may be missed in specialized clinics evaluating liver pathologies, due to its insidious onset, atypical clinical symptoms and multi-systemic involvement. It is prudent for diagnosticians and physicians to be aware of this entity and its imaging features, which may help as pointers to its diagnosis.

- Citation: Laroia ST, Lata S. Hypertension in the liver clinic - polyarteritis nodosa in a patient with hepatitis B. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(3): 94-98

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i3/94.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i3.94

India has a vast carrier pool of hepatitis B and C viruses, which are the leading causes of chronic hepatitis in the country[1]. Most of these patients, reporting to specialized liver hospitals and institutions are usually investigated and managed, primarily for liver and related issues. A small percentage (usually 6%-7%) may have subclinical or overt extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis[2,3]. These include glomerulonephritis, polyarteritis nodosa (PNA), aplastic anemia, cryoglobulinemia and other immune related disorders. It has been hypothesized that immune related mechanisms are responsible for such systemic extrahepatic manifestations in patients with hepatitis B[4].

A 56-year-old gentleman who had long standing history of hepatitis B antigen positive, presented to our liver hospital out-patient clinic with recent onset hypertension. No obvious associated symptoms were present. No history of fever, rash, arthralgia, visual disturbances, headaches, fatigue or change in urinary output could be elicited. Findings of physical examination were unremarkable. Examination of peripheral pulses revealed no asymmetry, bruit or radio-femoral delay. Renal bruit was absent. Laboratory tests revealed microcytic hypochromic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (Reference range 13-17 g/dL). The differential leukocyte counts were normal. Liver function tests showed mildly elevated liver enzymes with Aspartate Aminotransferase of 76 IU/L (Reference range 5-40 IU/L) and Alanine Aminotransferase of 104 (Reference range 10-40 IU/L). Serum proteins, Albumin: Globulin ratio and the bilirubin levels were normal. The renal function tests showed normal blood urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes and uric acid levels. Markers for hepatitis viruses showed the following results: Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was positive with negative hepatitis C antibodies. HBsAg and HBe antigen were reactive. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA was tested by real time polymerase chain reaction. Viral load at the time of presentation in the patient was 5.8 × 107 IU/mL.

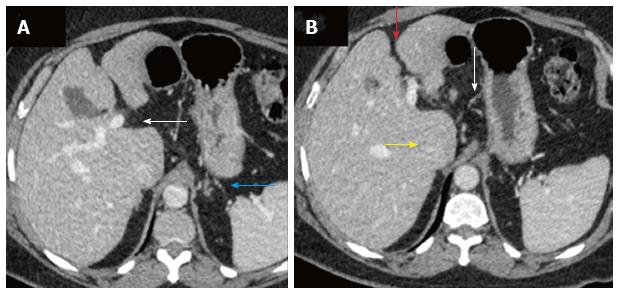

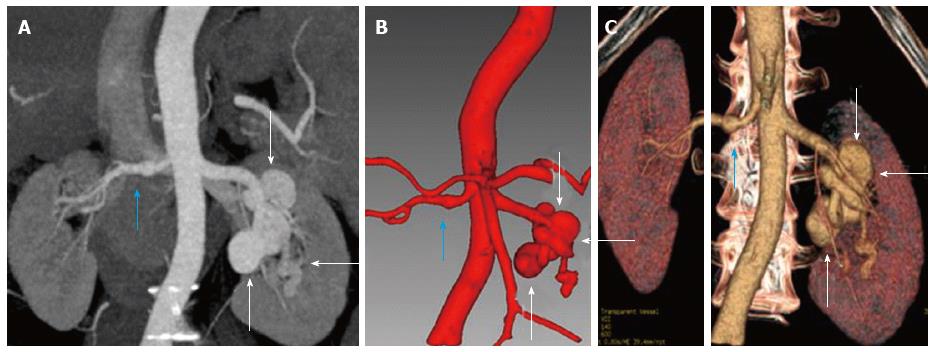

Multiphase dynamic computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed to evaluate the status and extent of parenchymal chronic liver disease. It showed imaging features of irregular contours of the liver, prominent caudate lobe and widened periportal space consistent with chronic liver disease (Figure 1). Incidentally, CT angiography revealed multiple aneurysms of main right and left segmental renal arteries, seen predominantly on the left side (Figure 2).

Immunology profile including antinuclear antibody and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies (anti MPO) were negative. These findings were in accordance with a diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa. Differential diagnoses of segmental arterial mediolysis (which is a non-inflammatory vasculopathy), Microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (which are ANCA-associated systemic vasculitides) were considered. These disorders have some features similar to those of classic PAN, with the additional involvement of renal glomeruli and pulmonary capillaries. These could however, be excluded with the help of imaging and laboratory findings, viral markers and subsequent therapeutic response. As per institute policy and standard guidelines, the patient was prescribed corticosteroids for initial two weeks to control the inflammatory damage to organs. Antiviral therapy with Lamivudine was started after the course of short term steroids to bring down the viral load and seroconversion of the patient. The follow up serology revealed conversion of hepatitis B e antigen to anti HBe antibody after six months. The patient made a good recovery without any significant side effects and tolerated the therapy well.

An abdominal CT performed after one year demonstrated no increase in the size and extent of the aneurysms and appeared as stable disease. The extent of liver disease also remained stable with no change in the liver size and no signs of decompensation or portal hypertension.

About one percent of HBV infected patients and less than one percent patients of HCV infection are known to develop PAN as an extrahepatic manifestation of liver disease[5,6]. These patients can develop features of PAN as early as, six months post infection[7]. Thirty percent patients of PAN have HBV infection as their etiological factor whereas the rest are idiopathic[5]. Microaneurysms are the most common presentation of PAN and are predominantly seen to involve the vasculature supply of kidneys, mesentery and liver[8]. Circulating immune complexes containing viral proteins, deposit in vessel walls of visceral arteries and induce focal inflammation resulting in stenosis and microaneurysms[9].

The diagnosis of HBV is based on serological demonstration of viral markers namely HBsAg, anti-HBsAg, immunoglobulin M, anti hepatitis B core (HBc) antibody and HBV DNA[1]. Clinical presentation of PAN includes involvement of cutaneous and peripheral nerves, vessels as well as multisystemic vasculitis. Diagnosis may be made with the help of muscle, skin or nerve biopsy and in cases of visceral involvement by angiography to demonstrate multiple aneurysms[10]. Isolated multiple bilateral renal aneurysms are very rare and the most common cause would be systemic vasculitis such as seen in PAN, as was present in our patient. Hypertension is an indirect presentation of renal artery aneurysms which cause segmental dilatation and stenosis of the renal vessels due to aneurysm formation.

In a case where hepatitis B is concomitantly present with an extrahepatic manifestation such as PAN, management would consist of combined immunosuppressant and antiviral therapy[4]. Recent role of plasmapheresis has been emphasized in clearing up circulating immune complexes in this group of patients. Remission of PAN is associated with the loss of HBV DNA replication. This was also observed in the patient described in our study above. The 5-year survival has been predicted as 75%[11].

Renal or peri-renal haematomas may result from the rupture of microaneurysms. The indications for treatment of a renal artery aneurysm are the presence of intra-aneurysmal clots, hypertension and potential for rupture.

Hypertension in the liver clinic may be the only manifestation of PAN; hence this association should be ruled out using imaging techniques such as CT angiography, for better management of this subgroup. All physicians need to be aware of concomitant presentation of PAN as hypertension and systemic vascular aneurysms in a patient of chronic liver disease.

A middle aged gentleman with history of positive hepatitis B antigen, presented to the out-patient clinic of the liver care hospital with recent onset hypertension.

The physical examination including examination of renal bruit, peripheral pulses and clinical history pertaining to the symptoms were unremarkable, hence essential hypertension with chronic liver disease was the working clinical diagnosis.

Included: Essential hypertension with underlying liver disease, renal artery stenosis with chronic liver disease, chronic renal and liver disease leading to hypertension.

The patient’s laboratory tests revealed microcytic hypochromic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 gm/dL. The differential leukocyte counts were normal. Liver function tests showed mildly elevated liver enzymes with aspartate aminotransferase of 76 IU/L (Reference range 5-40 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 104 (Reference range 10-40 IU/L). Serum proteins, Albumin: Globulin ratio and the bilirubin levels were normal. The renal function tests showed normal blood urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes and uric acid levels. Hepatitis B surface antigen was positive. Hepatitis B surface antigen and HBe antigen were reactive. Hepatitis B virus DNA was tested by real time polymerase chain reaction. Viral load at the time of presentation in the patient was 5.8 × 107 IU/mL.

Multiphase dynamic computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed irregular contours of the liver, prominent caudate lobe and widened periportal space consistent with chronic liver disease with incidental CT angiography revealing multiple aneurysms of the main right and segmental left renal arteries.

Immunology profile including antinuclear antibody and antimyeloperoxidase antibodies (anti MPO) were negative and no further biopsy was carried out to rule out cause of the vasculitis like process due to the well-known association of polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) with hepatitis B infection and classical imaging findings.

As per institute policy and standard guidelines, the patient was prescribed corticosteroids for two weeks to control the inflammatory damage to organs. Antiviral therapy with Lamivudine was started after the course of short term steroids to bring down the viral load and seroconversion of the patient. The follow up serology revealed conversion of hepatitis B e antigen to anti HBe antibody after six months.

Very few cases of isolated renal, multiple bilateral aneurysms, which are usually otherwise seen in systemic vasculitis have been reported in literature. In our case study, the unusual finding of PAN indirectly presenting as hypertension due to renal artery aneurysms with resultant segmental dilatation and stenosis in a case of underlying chronic liver disease has been highlighted.

PAN is an immune system related disorder where circulating immune complexes containing viral proteins, deposit in vessel walls of visceral arteries and induce focal inflammation resulting in stenosis and microaneurysms commonly involving the vasculature supply of kidneys, mesentery and liver.

Hypertension in the liver clinic may be the only manifestation of PAN and should be ruled out using imaging techniques such as CT angiography for better management of this subgroup. All physicians need to be aware of concomitant presentation of PAN as hypertension and systemic vascular aneurysms in a patient of chronic liver disease.

This study reports the case of PAN in a 56-year-male patient with a history of hepatitis B infection. This case illustrates the unusual presentation, hypertension, of extrahepatic manifestation of viral hepatitis in the form of PAN of kidneys. This case has the reference value for clinical settings. The manuscript’s presentation is well and readable.

| 1. | Puri P. Tackling the Hepatitis B Disease Burden in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:312-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baig S, Alamgir M. The extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis B virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:451-457. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Amarapurkar DN, Amarapurkar AD. Extrahepatic manifestations of viral hepatitis. Ann Hepatol. 2002;1:192-195. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rodrigo D, Perera R, de Silva J. Classic polyarteritis nodosa associated with hepatitis C virus infection: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mahr A, Guillevin L, Poissonnet M, Aymé S. Prevalences of polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome in a French urban multiethnic population in 2000: a capture-recapture estimate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:92-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Timmeren MM, Heeringa P, Kallenberg CG. Infectious triggers for vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ebert EC, Hagspiel KD, Nagar M, Schlesinger N. Gastrointestinal involvement in polyarteritis nodosa. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:960-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lhote F, Cohen P, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Lupus. 1998;7:238-258. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Guillevin L, Mahr A, Callard P, Godmer P, Pagnoux C, Leray E, Cohen P. Hepatitis B virus-associated polyarteritis nodosa: clinical characteristics, outcome, and impact of treatment in 115 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:313-322. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hernández-Rodríguez J, Alba MA, Prieto-González S, Cid MC. Diagnosis and classification of polyarteritis nodosa. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:84-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huang WH, Wang LJ, Yu CC, Lin JL. Bilateral renal aneurysms in a chronic hepatitis B patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:276-277. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Gui X S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL