Published online Sep 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i9.843

Peer-review started: October 21, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: April 15, 2015

Accepted: June 1, 2015

Article in press: June 2, 2015

Published online: September 16, 2015

Processing time: 330 Days and 16 Hours

Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is a life-threatening infection in immunocompromised patients. It is relatively uncommon in patients with lung cancer. We report a case of PCP in a 59-year-old man with a past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with formoterol and a moderate daily dose of inhaled budesonide. He had also advanced stage non-small lung cancer treated with concurrent chemo-radiation with a cisplatin-etoposide containing regimen. The diagnosis of PCP was suspected based on the context of rapidly increasing dyspnea, lymphopenia and the imaging findings. Polymerase chain reaction testing on an induced sputum specimen was positive for Pneumocystis jirovecii. The patient was treated with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and systemic corticotherapy and had showed clinical and radiological improvement. Six months after the PCP diagnosis, he developed a malignant pleural effusion and expired on hospice care. Through this case, we remind the importance of screening for PCP in lung cancer patients under chemotherapeutic regimens and with increasing dyspnea. In addition, we alert to the fact that long-term inhaled corticosteroids may be a risk factor for PCP in patients with lung cancer. Despite intensive treatment, the mortality of PCP remains high, hence the importance of chemoprophylaxis should be considered.

Core tip:Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is relatively uncommon in patients with lung cancer. We report a case of PCP in a 59-year-old man with a past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with formoterol and a moderate daily dose of inhaled budesonide. He had also advanced stage non-small lung cancer treated with concurrent chemo-radiation. This report attempts to alert for the importance of PCP screening in lung cancer patients under chemotherapeutic regimens and with increasing dyspnea. It also alerts to the role of long-term inhaled corticosteroids as a risk factor for PCP in patients with lung cancer.

-

Citation: Msaad S, Yangui I, Bahloul N, Abid N, Koubaa M, Hentati Y, Ben Jemaa M, Kammoun S. Do inhaled corticosteroids increase the risk of

Pneumocystis pneumonia in people with lung cancer? World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(9): 843-847 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i9/843.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i9.843

Patients with hematological and oncological diseases are at increased risk for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) because of their disease-related and therapy-induced immunosuppression[1]. However, PCP among lung cancer patients is probably an under-diagnosed complication whose incidence is still unknown and risk factors remain incompletely identified. We report here a case of PCP in a 59-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) under long-term inhaled corticosteroid therapy and receiving a concomitant radio-chemotherapy for stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer.

We report the case of a 59-year-old man with a 50 pack-year smoking history. He had moderate COPD treated with formoterol and moderate doses of inhaled budesonide (800 μg/d). He was admitted to our hospital in March 2012 for hemoptysis and evaluation of a right upper lobe lung mass with invasion of the mediastinal pleura and ipsilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT)-guided needle lung biopsies were positive for squamous cell carcinoma of the lungs. Additional work-up using abdominal and brain CT did not detect any extra-thoracic metastases. Thus, the disease was clinically classified as stage IIIB (T3N2M0). From May to November 2012, he had undergone five cycles of etoposide 100 mg/m2 and cisplatin 20 mg/m2 chemotherapy given in combination with 32 rounds of radiotherapy at 74 Gray. Two months after the first chemotherapy cycle, the patient developed grade II persistent lymphopenia (750-1000 cells/mm3). A control CT scan performed in December 2012 showed partial remission.

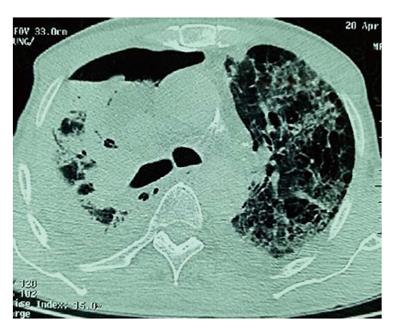

Four months later, the patient came to the emergency department with a ten-day history of increasing breathlessness and fever without any other symptoms (in particular, there was neither chest pain nor hemoptysis). Upon examination, his temperature was 36.7 °C, pulse was 120 bpm, respiratory rate was 33 breaths/min and blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg. His oxygen saturation was 99% on room air and his body mass index was 22 kg/m2. Over the right lower lobe lung, decreased breath sounds and decreased tactile fremitus with dullness to percussion were noted. Results of the remainder of the examination were entirely normal. Chest X-ray showed a tumor in the right upper lobe. Nodular parenchymal infiltrates appeared in the left upper lobe lung. A little right pleural effusion was also noticed (Figure 2). An arterial blood gas obtained with the patient breathing room air showed pH = 7.41, pCO2 = 40.6 mmHg, pO2 = 68 mmHg, HCO3- = 27.2, and O2Sat = 94.5%. Laboratory investigations showed a hemoglobin level of 12.7 g/dL, a leucocyte count of 8030/mm3 with a differential of 81% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 10% lymphocytes (lymphopenia at 803/mm3), 7% monocytes, 1% eosinophiles and a platelet count of 329.000/mm3. The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 86 mm/h, and C-reactive protein was 58 mg/dL. Protein level in the blood was 29 g/dL. Serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase were all within normal limits. Purified protein derivative for a tuberculous skin test was non-reactive. Three acid fast bacilli smears and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing were negative. The patient received 3 g of cefotaxim three times a day. On the fourth day in the hospital, his dyspnea was exacerbated and an arterial blood gas obtained on room air showed pH = 7.47, pCO2 = 39.6 mmHg, pO2 = 44.8 mmHg, HCO3 = 21.9, and O2Sat = 83.9%. A thoracic CT scan eliminated pulmonary embolism. However, it showed, in addition to the primitive tumor, widespread thin-walled cysts and nodules throughout the lungs but most prominent at the right lung. There were also a small right apical pneumothorax and a small bilateral pleural effusion (Figure 3). Pleural fluid was transudative and cultures were negative. The diagnosis of PCP was suspected based on the context of rapidly increasing dyspnea, lymphopenia following treatment with chemoradiation and the imaging findings. Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage was indicated but could not be performed because of severe hypoxemia. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing on an induced sputum specimen was positive for Pneumocystis Jirovecii.

Treatment for PCP was started with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) given orally three times a day at a dose of 20 mg/kg per day with TMP and 100 mg/kg per day with SMX (12 tablets of co-trimoxazole daily). A short course of high-dose dexamethasone (120 mg/d) was also given intravenously for three consecutive days followed by 1 mg/kg per day of prednisone with gradual tapering.

The patient showed clinical and radiological improvement and was discharged after hospitalization for a month with instructions to complete 21 d of treatment with TMP-SMX and one month of corticotherapy. Since then, he has been seen at our hospital once a month and he remained stable during two months. In July 2013, he was re-admitted for rapid deterioration of the general status. He reported also a shortness of breath that gradually worsened. A follow-up thoracic CT scan showed a large right pleural effusion. A needle pleural biopsy confirmed metastatic pleurisy. Therapeutic abstention was decided because of the deep deterioration of the general status, and the patient received just palliative care. He expired three months later. An autopsy was not performed.

PCP is an opportunistic life-threatening fungal infection caused by Pneumocystis Jirovecii. It is seen in immune-compromised individuals, primarily among HIV-infected patients[2]. However, the increasingly frequent use of immunosuppressive drugs had led to outbreak for PCP in patients not infected by HIV[1]. We report here a case of PCP in a patient with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer treated by cisplatin/etoposide concurrent chemoradiation therapy. PCP is relatively uncommon in patients with lung cancer. Its incidence remains unknown. Recent evidence suggests that about 0.11% of the patients with solid malignancies developed PCP (30 cases of PCP among 26085 patients)[3]. In another retrospective investigation of 150 lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy during 1 year, authors found a low incidence of clinical PCP, less than 1%. However, there was a relatively higher (31%) percentage of PCP positivity in patients who developed pneumonia while being treated for lung cancer than in those being treated for other solid tumors[4]. The incidence of PCP in patients with solid tumors has recently increased, probably because of better overall survival and use of more aggressive chemotherapy[5]. The higher risk has been reported with vincristine and cyclophosphamide, but less communally with platinum-based regimens[2,5,6]. With these cytostatic agents, the risk of developing PCP depends on the severity and the duration of neutropenia[1]. Moreover, patients receiving their first cycle of chemotherapy are at a higher risk of infection than in following cycles[1]. In our case, the diagnosis of PCP was not initially suspected because of the long time from the completion of chemotherapy to the onset of pneumonitis and the absence of neutropenia. However, the patient should be regarded as a host risk for PCP due to additional factors such as the advanced stage of the underlying malignancy, associated comorbidities (COPD), the use of radiotherapy as well as inhaled corticosteroid therapy[1,7]. In fact, radiation to the thorax can increase the risk of developing PCP by producing significant lung parenchymal lesions or by causing lymphocyte-depleting as was observed in our case[7]. Paradoxically, it has been reported that PCP infiltrates may spare the area of the lung that is included in a radiation port either during the course of therapy or several months after[7,8]. In our patient, the pulmonary infiltrates were more prominent on the left lung compared to the previously irradiated right side. This presentation called “photographic negative of post-radiation pneumonia” is a distinct finding in PCP[9].

Most patients undergoing chemotherapy for solid tumors received corticosteroids at the time of the PCP diagnosis[2,5]. In fact, it has been long known that systemic corticosteroid treatment is a major and a common factor for PCP, and accounts for 55% to 99% of published cases in non-HIV infected patients[10]. For instance, a dose of 30 mg of prednisone or the equivalent for 12 wk is considered a significant risk factor[6,8]. The mechanism could be a decrease of blood CD4+ lymphocyte count[11]. Nevertheless, the impact of inhaled corticosteroid on the risk of infection is still unknown. On reviewing the medical literature, we only found one case of association between inhaled corticosteroid and PCP in a lung cancer patient with COPD[7]. Another case was also described in one asthmatic child[12]. These reports suggest that long term inhaled corticosteroid should be considered a risk factor for PCP especially in immune-compromised hosts such as COPD or lung cancer patients, even in the absence of marked leucopenia[7]. However, the magnitude of this risk, the effects of different preparations and doses, and the mechanisms of this effect remain unclear[13]. Of the inhaled corticosteroids studied, only fluticasone demonstrated a dose-related increase in risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD. This difference between fluticasone and budesonide may be explained by the longer retention of fluticasone in the airways, with potentially greater inhibition of type-1 innate immunity[14]. More studies are needed to understand the increased PCP risk with inhaled corticosteroids.

The outcome of PCP in patients without HIV infection is worse than that in HIV-positive patients[15] with a higher mortality (30%-60% vs 10%-20%)[16]. Despite its poor outcome, the need for primary PCP prophylaxis in patients with lung cancer is still considered less clear or even questioned by some authors. Several studies recommended that PCP prophylaxis should be performed if patients with lung cancer received prolonged systemic corticosteroids, prednisone or equivalent at least 20 mg for more than 4 wk[17]. Our patient did not receive any PCP prophylaxis because he was not under long-term steroid medication. He was just receiving long-term inhaled corticosteroids that might be, as already mentioned, a risk factor for PCP, even if it has not yet been clearly demonstrated[7]. This fact should lead to discussing prophylaxis in patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids, on a case-by-case basis, even without any specific recommendation.

Long-term inhaled corticosteroids may be linked with an increased risk of PCP in lung cancer patients with COPD, even in the absence of marked pneumonia. More studies are needed to clarify the magnitude of this risk, the effects of different preparations and doses, and the mechanisms of this effect. In lung cancer patients under long-term inhaled corticosteroids, chemoprophylaxis should be considered, although its indication and duration are still controversial.

A case of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in a 59-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases under long-term inhaled corticosteroid therapy and receiving a concomitant radio-chemotherapy for stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer.

Increasing breathlessness and fever.

Bacterial pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Lymphocyte percentage was 10% (lymphopenia at 803/mm3), erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 86 mm/h, C-reactive protein was 58 mg/dL, protein level in the blood was 29 g/dL, purified protein derivative for a tuberculosis skin test was non-reactive and three acid fast bacilli smears and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing were negative.

Thoracic computed tomography scan showed a primitive tumor with widespread thin-walled cysts and nodules throughout the lungs, most prominent at the right lung, associated with a small right apical pneumothorax and a small bilateral pleural effusion.

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Twenty-one days of treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and one month of systemic corticotherapy.

The increasingly frequent use of corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and other immunosuppressive drugs had led to outbreak for PCP in patients not infected by HIV, in particular in oncological diseases such as lung cancer.

Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) is a fungal opportunistic pathogen found in immunocompromised patients. It has gained particular prominence since the onset of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome epidemic.

PCP should be suspected in lung cancer patients with increasing dyspnea if they have risk factors such as chemotherapy and prolonged systemic corticosteroids or even long-term inhaled corticosteroids.

The subject is interesting.

| 1. | Neumann S, Krause SW, Maschmeyer G, Schiel X, von Lilienfeld-Toal M. Primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors: guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol. 2013;92:433-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tasaka S, Tokuda H. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in non-HIV-infected patients in the era of novel immunosuppressive therapies. J Infect Chemother. 2012;18:793-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sepkowitz KA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia among patients with neoplastic disease. Semin Respir Infect. 1992;7:114-121. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mori H, Ohno Y, Ito F, Endo J, Yanase K, Funaguchi N, Bai La BL, Minatoguchi S. Polymerase chain reaction positivity of Pneumocystis jirovecii during primary lung cancer treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:658-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Roux A, Gonzalez F, Roux M, Mehrad M, Menotti J, Zahar JR, Tadros VX, Azoulay E, Brillet PY, Vincent F. Update on pulmonary Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in non-HIV patients. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:185-198. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Roblot F, Godet C, Kauffmann C, Tattevin P, Boutoille D, Besnier JM. Current predisposing factors for Pneumocystis pneumonia in immunocompromised HIV-negative patients. JMM. 2009;19:285-289. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tsai SH, Lin YY, Wu YC, Chu SJ, Wu CP. Pulmonary Opportunistic Infections in A Lung Cancer patient treated by inhaled corticosteroid. J Intern Med Taiwan. 2009;20:92-96 Available from: http://www.tsim.org.tw/journal/jour20-1/12.pdf. |

| 8. | Velcheti V, Govindan R. Pneumocystis pneumonia in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with pemetrexed containing regimen. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:240-242. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kim HH, Park SH, Kim SC, Kim YS. Altered distribution of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia during radiation therapy. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1577-1578. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Fily F, Lachkar S, Thiberville L, Favennec L, Caron F. Pneumocystis jirovecii colonization and infection among non HIV-infected patients. Med Mal Infect. 2011;41:526-531. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Bollée G, Sarfati C, Thiéry G, Bergeron A, de Miranda S, Menotti J, de Castro N, Tazi A, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Clinical picture of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in cancer patients. Chest. 2007;132:1305-1310. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sy ML, Chin TW, Nussbaum E. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia associated with inhaled corticosteroids in an immunocompetent child with asthma. J Pediatr. 1995;127:1000-1002. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Finney L, Berry M, Singanayagam A, Elkin SL, Johnston SL, Mallia P. Inhaled corticosteroids and pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:919-932. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Latorre M, Novelli F, Vagaggini B, Braido F, Papi A, Sanduzzi A, Santus P, Scichilone N, Paggiaro P. Differences in the efficacy and safety among inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)/long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA) combinations in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Role of ICS. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;30:44-50. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ko Y, Jeong BH, Park HY, Koh WJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kwon OJ, Jeon K. Outcomes of Pneumocystis pneumonia with respiratory failure in HIV-negative patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29:356-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thomas CF, Limper AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487-2498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Baden LR, Bensinger W, Angarone M, Casper C, Dubberke ER, Freifeld AG, Garzon R, Greene JN, Greer JP, Ito JI. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:1412-1445. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Esteves F, Vetvicka V S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu SQ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/