INTRODUCTION

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) was first described in 1989[1,2]. DSRCT is a rare, aggressive malignant neoplasm of unknown origin, and is comprised of small round cells with a characteristic desmoplastic stroma. DSRCT is most common in children and young adults (mean age 22 years), with a male predominance (male to female ratio 4:1)[3]. The most common location is the abdominal and/or pelvic cavity, but it has been described in many organ systems, including ovary, paratesticular region, kidney, lung, pleura, parotid gland and central nervous system[4-11]. Typically, DSRCT has a distinctive immunohistochemical profile and expresses polyphenotypic markers simultaneously. The tumor cells usually express epithelial (cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen), mesenchymal (desmin, vimentin) and neural (neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin, synaptophysin) markers. Desmin immunoreactive displays in a perinuclear dot-like Golgi pattern. DSRCTs with atypical morphology or immunohistochemical features have been reported[12,13]. Cytogenetics, FISH, RT-PCR and molecular testing are crucial in rendering the correct diagnosis[14].

DSRCT is associated with a unique chromosomal translocation t(11:22)(p13;q12) which involves the Ewing sarcoma gene breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) on 22q13 and the Wilms tumor gene (WT1) on chromosome 11p13[15]. EWSR1 gene encodes EWS protein, which is a multifunctional protein associated with gene expression, cell signaling, and RNA processing and transport. WT1 is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes a zinc finger protein which regulates several growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGFA)[16]. The most common breakpoints involve the intron between EWSR1 exon 7 and 8 and the intron between WT1 exons 7 and 8, although breakpoint variations have been described[17-19].

CASE REPORT

An 8 years old male with no known significant past medical history presented with 1 wk history of vague abdominal pain. The child was afebrile, had regular bowel movements, tolerated a regular diet, and denied nausea and vomiting. Physical examination showed a mildly distended abdomen without a readily palpable mass. CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 17-cm heterogeneously enhancing complex cystic lesion, which displaced the colon and small intestine laterally and superiorly. On exploratory laparotomy, the mass was adherent to the omentum. The mass was tossed, with large dilated blood vessels on the external surface of the tumor. The patient tolerated the surgical procedure well.

Gross pathology

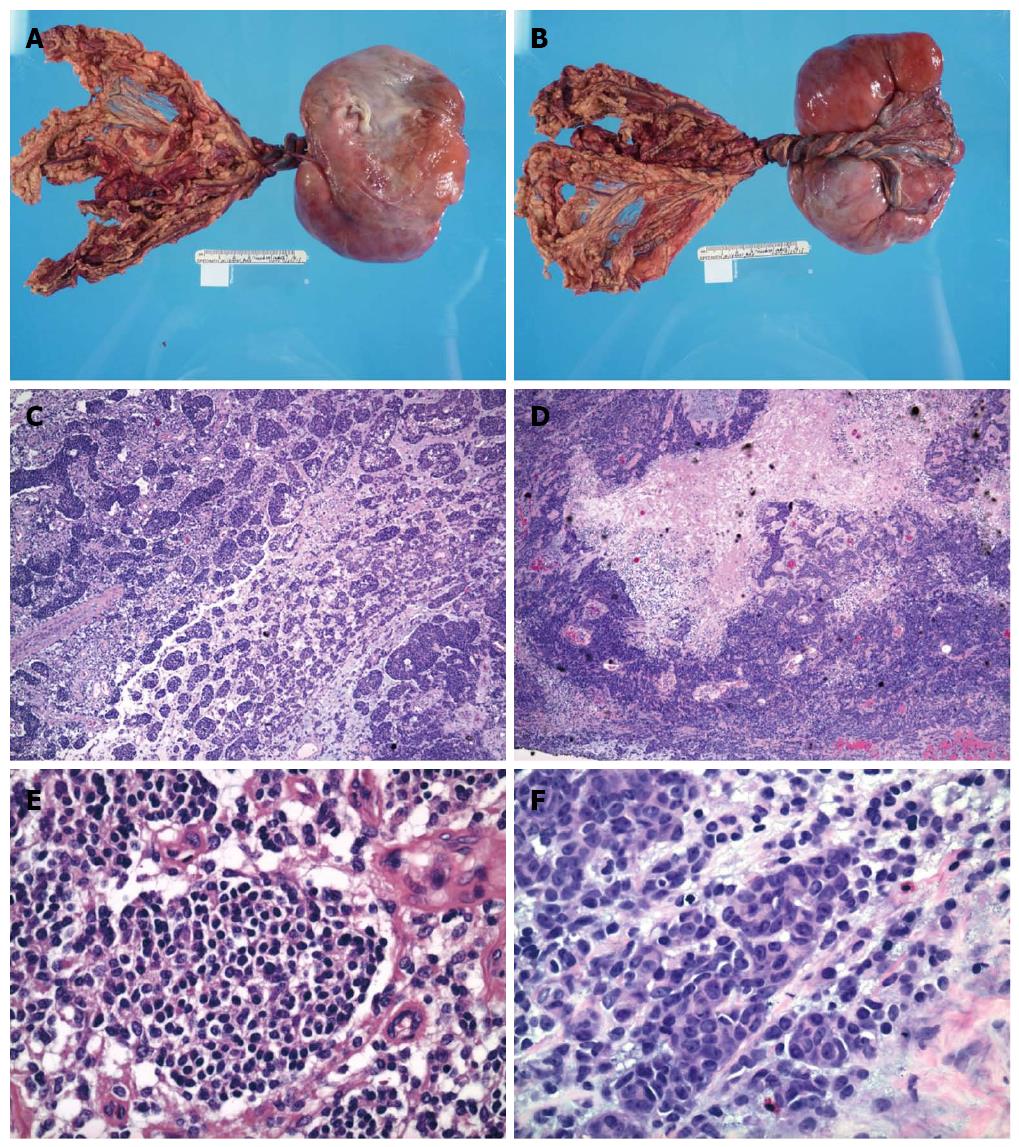

Upon gross examination, the mass was encapsulated, lobulated and measured 17.0 cm × 11.0 cm × 5.0 cm, with attached omental tissue (Figure 1A, B). Cross sections of the mass showed variegated cut appearance ranging from tan to red to black in color. Focal areas of hemorrhage and necrosis were noted.

Figure 1 Gross and microscopic feature of abdominal mass.

A, B: Gross examination showed an encapsulated and lobulated soft tissue mass with attached omental tissue; C-F: The small round cell tumor possessed round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm. Focal tumor cells with enlarged nuclei, open chromatin and prominent nucleoli, as well as rhabdoid differentiation were noted. Focal tumor necrosis and hemorrhages were present (HE staining).

Microscopic and immunohistochemical features

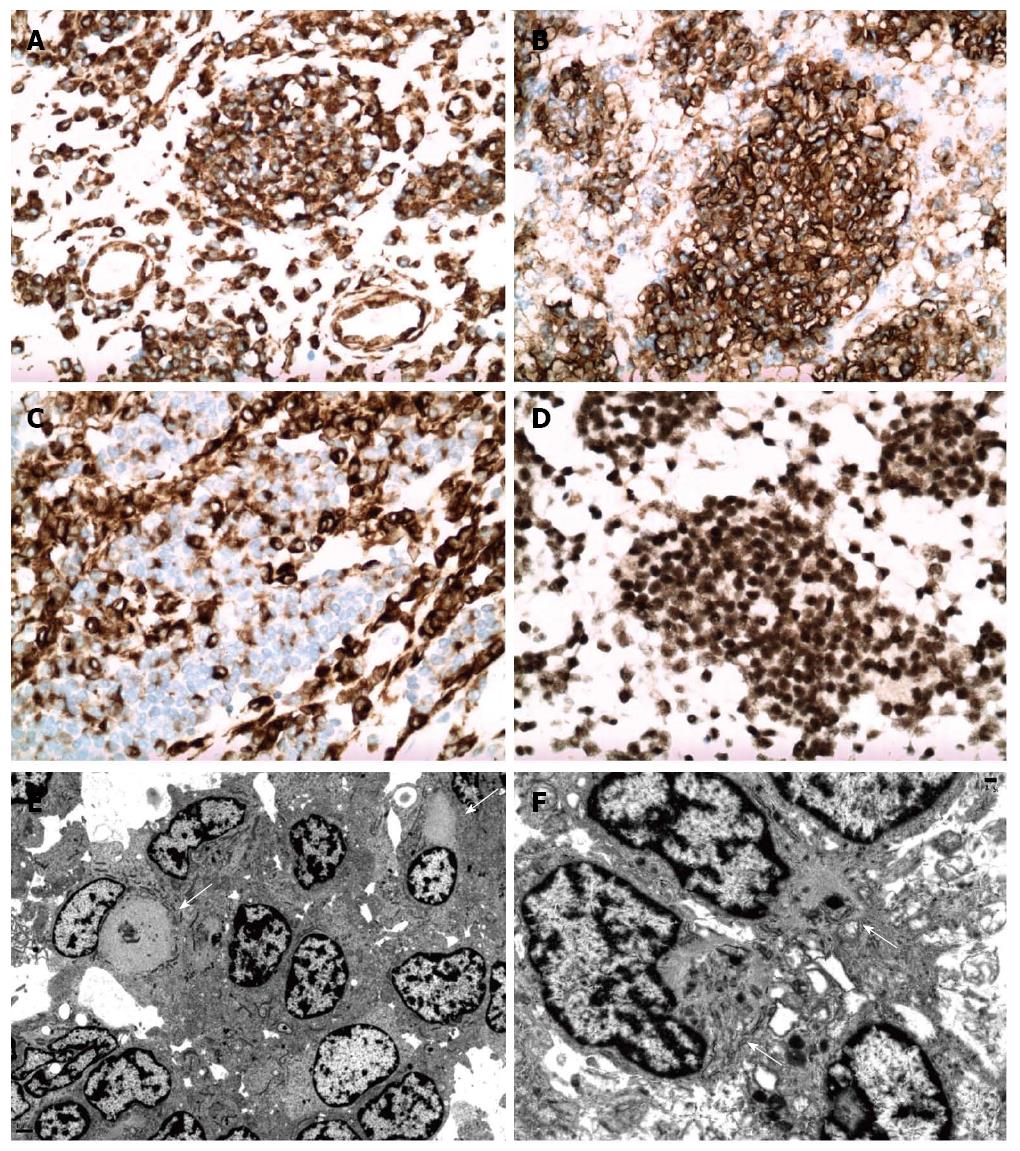

Microscopic examination showed small round cell aggregates embedded in a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1C-F). The tumor cells were round to oval with scant cytoplasm, hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. However, certain tumor cells have a different histomorphologic appearance with enlarged nuclei, open chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Focal tumor necrosis and hemorrhage were present, corresponding to these features seen upon gross examination. Prominent vascular proliferation was associated with the tumor. An atypical immunophenotype (Figure 2A-D) was demonstrated. The tumor cells were positive only for vimentin, desmin (cytoplasmic membranous pattern) and CD56, while being negative for smooth muscle actin, synaptophysin, CD117, CD45, myogenin, CAM5.2, pancytokeratin, WT1, EMA, CD99, neurofilament, CD34 and p53. Ki67 showed a low proliferative activity.

Figure 2 Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of abdominal mass.

Tumor cells exhibited strong diffuse cytoplasmic vimentin expression (A), diffuse membranous CD56 expression (B), cytoplasmic and membranous desmin expression (C), and nuclear INI-1 reactivity (SNF-5/BAF47) with tumor cells and non-neoplastic cells. Electron microscopy (E, F) showed closely apposed tumor cells with irregular nuclear outlines and heterochromatin. There were intermixed tumor cells with aggregates and whirls of intermediate filaments (arrows) that displaced the nuclei and entrapped organelles.

Ultrastructural features

Electronic microscopy (Figure 2E, F) showed closely apposed tumor cells with rudimentary intercellular junctions and without myofilaments, dense core neurosecretory granules, cytokeratin-like intermediate filaments and no glycogen aggregates. The tumor cells had irregular nuclear outlines, prominent heterochromatin and moderate cytoplasm. There was readily identified rhabdoid differentiation within a certain population of tumor cells. These tumor cells had large aggregates of cytoplasmic filaments that displaced the nuclei to the periphery of the cell, with some tumor cells having indented nuclear profiles. There were also entrapped organelles within cytoplasmic filament whirls. Upon discovery of these rhabdoid cells on ultrastructural examination, immunohistochemical staining for INI-1 (SNF-5/BAF47) was performed. Surprisingly, all tumor cells demonstrated preservation of nuclear positivity, eliminating rhabdoid tumor from the differential diagnosis.

Cytogenetics

Upon cytogenetic analysis, the karyotype of the cultured tumor cells was shown to be 46,XY, t(11;22)(p13;q12)[12]/92, idemx2[4] with t(1;15)(q11;p11.2). The t(11;22) translocation harbored the EWSR1-WT1 translocation, a tumor-defining feature of DSRCT. A diagnosis of DSRCT with rhabdoid-like cell component was rendered.

DISCUSSION

The differential diagnosis of a “small round cell tumor” includes Ewing sarcoma, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, small cell osteosarcoma, small cell synovial sarcoma, small cell carcinoma, lymphoma, and rhabdoid tumor. DSRCT has characteristic immunohistochemical features, with expression of epithelial, mesenchymal and neural markers simultaneously, which is helpful in differentiating DSRCT from other “small round cell tumors”. However in the present case, the tumor cells were negative for many epithelial, myogenic and neural markers and positive only for vimentin, CD56 and desmin. CD56 is a nonspecific marker, and expressed in many “small round cell tumors”, including alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, neuroendocrine neoplasms and undifferentiated sarcoma[20]. Desmin showed a cytoplasmic membranous pattern, instead of the typical perinuclear dot-like Golgi pattern characteristic for DSRCT. The atypical immunohistochemical features made it difficult to make a correct diagnosis by morphologic and immunohistochemical features alone. DSRCT lacking epithelial markers and/or divergent immunophenotype has been described in several reports[12,13,21]. Cytogenetic and molecular studies are crucial in these cases in rendering an accurate diagnosis.

DSRCT can have many morphologic variations[22-24]. In our case, focal rhabdoid differentiation was identified on EM. However, the nuclear expression of SNF-5(INI1/BAF47) was preserved in the tumor cells, which did not support a diagnosis of rhabdoid tumor. The ultrastructural features of DSRCT include intracellular whirls and packets of intermediate filaments that usually fill the cytoplasm and displace the nucleus, while entrapping cytoplasmic organelles within the filaments[25-27]. Rhabdoid differentiation, as well as focal areas with increased nuclear atypia, has been previously described in DSRCT [28]. Although DSRCT usually has a desmoplastic stroma, this was not present in our case. Prominent vascular proliferation can be seen in DSRCT, as in our case, and the differential diagnosis of infiltrating glomus tumor may be entertained. However, infiltrating glomus tumor typically expresses smooth muscle actin and variably desmin. Other morphologic variations previously described in DSRCT, such as signet ring-like appearance, “zellballen” pattern, tubular-like structure or papillary areas were not identified in our case[23,29].

Interestingly, our case not only had an unusual immunohistochemical profile, but also a unique karyotype. Cytogenetic study showed translocation t(11;22)(p13;q12), which is characteristic of DSRCT, and an additional translocation t(1;15)(q11;p11.2). Even though the characteristic EWSR1/WT1 translocation can be detected by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), cytogenetic testing is necessary to detect tumor-defining translocations, novel translocations and complex karyotypic aberrations. Of note, the INI-1 (hSNF5) gene is located at 22q11.2 in close proximity to EWSR1. This close proximity may have led to dysregulation of the IN1-1 gene function without loss of INI-1 gene protein expression. Rhabdoid tumors without INI-1 gene loss or mutation and expression of INI-1 gene protein have been reported[30]. These rhabdoid tumors have loss or mutation of SMARCA4 (19p13.2) which dysregulates a signaling pathway downstream from INI-1 gene protein function. In an extensive search of the English language literature, the t(1;15)(q11;p11.2) has not been previously reported in pediatric neoplasia. Of interest, translocations involving 1q11 have been reported in myelodysplastic syndromes. The pericentromeric region of chromosome 1 is an unstable region involved in several chromosomal rearrangements. A possibility is that the heterochromatin of chromosome 1 may have a silencing effect, or otherwise interfering effect, with genes present in the region involved in the translocation. Few myelodysplastic syndrome cases with a der(1;15) translocation have been reported[31].

In the present case, infrequent tumor cells also showed tetraploid clonal evolution, which is common in many tumors and has been previous reported in DSRCT[32]. Our hypothesis is that the unusual immunohistochemical profile in our case was due to the complex karyotype. It is debatable if the tumors with complex karyotype should still be called DSRCT or a new category of “gray zone small blue cell tumor” should be created in the future. Currently, no standard oncologic therapy is available for DSRCT and the prognosis is dismal even with multimodality oncologic therapy[33-35]. The 5-year survival rate is approximately 15%[35]. The prognosis significance of DSRCT with complex karyotype is currently unclear.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

An 8 years old male with no known significant past medical history presented with 1 wk history of vague abdominal pain.

Clinical diagnosis

The child was afebrile, had regular bowel movements, tolerated a regular diet, and denied nausea and vomiting. Physical examination showed a mildly distended abdomen without a readily palpable mass.

Differential diagnosis

Electronic computer X-ray tomography technique of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a 17-cm heterogeneously enhancing complex cystic lesion, which displaced the colon and small intestine laterally and superiorly.

Treatment

The authors describe a case of desmoplastic small round cell tumor with an atypical immunohistochemical profile and rhabdoid-like tumor cells on electron microscopy.

Experiences and lessons

This case is a diagnostic challenge because of atypical immunohistochemical profile and cytogenetic study is crucial in rendering the correct diagnosis.

Peer review

The authors report an atypical small round cell tumor case. The manuscript is clearly written and the case is of interest.