Published online Apr 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.90

Revised: January 12, 2014

Accepted: March 13, 2014

Published online: April 16, 2014

Processing time: 183 Days and 9 Hours

Left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication that is reported in less than 0.1% of all patients with myocardial infarction. It is the result of cardiac rupture contained by the pericardium and is characterized by the absence of myocardial tissue in its wall unlike true aneurysm which involves full thickness of the cardiac wall. The clinical presentation of these patients is nonspecific, making the diagnosis challenging. Transthoracic echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging are the noninvasive modalities whereas coronary arteriography and left ventriculography are invasive modalities used for the diagnosis. As this condition is lethal, prompt diagnosis and timely management is vital.

Core tip: Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm is a rare and lethal condition. It can be challenging to diagnose as it has an ambiguous clinical presentation. Timely recognition and management is critical and can be lifesaving.

- Citation: Alapati L, Chitwood WR, Cahill J, Mehra S, Movahed A. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(4): 90-93

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i4/90.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.90

Left ventricular (LV) pseudoaneurysm is a lethal condition, but the diagnosis and differentiation from LV true aneurysm is challenging as the clinical presentation of LV pseudoaneurysm is non-specific. We describe a 75-year-old patient who presented with symptoms and signs of myocardial infarction and was diagnosed to have LV pseudoaneurysm.

A 75-year-old african american female with hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, gout, status post coronary artery bypass graft and aortic valve replacement with bio-prosthetic valve performed a year ago, presented to the emergency department two weeks after mitral and tricuspid valve repair surgery, with shortness of breath, cough and chest pain for 2-3 d.

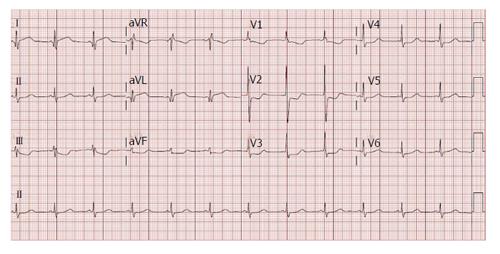

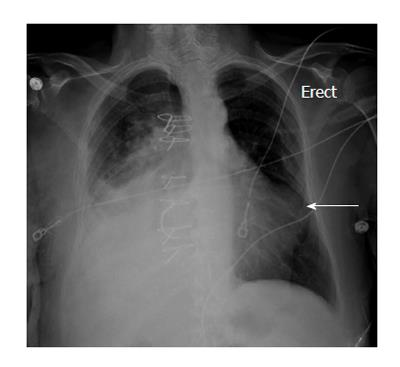

Her medications included aspirin, hydrochlorthiazide, irbesartan, simvastatin, verapamil and metformin. Vital signs on presentation were heart rate 74/min, blood pressure 127/56 mmHg, respiratory rate 16/min, temperature of 97.4 F and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. On physical examination, patient had normal S1 and S2, grade 2/6 systolic murmur heard over the aortic area, no gallops, no rub, and no jugular venous distension. There were diminished breath sounds in the mid and lower right lung fields and crackles over the left lower lung field. Trace bilateral lower extremity edema was present. Her white blood cell count: 13.50 k/μL, hemoglobin: 10.2 g/dL, hematocrit: 31.2%, platelets: 334 k/μL, creatinine: 0.74 mg/dL, troponin: 4.00 ng/mL, total creatinine phosphokinase: 75 U/L, creatinine kinase myocardial band: 10.4 ng/dU. An electrocardiogram showed 1.5 to 2 mm ST elevation in I, aVL, 1 to 2 mm ST depression in II, aVF, V1 to V4, and R/S ratio > 1 in V1 and V2 (Figure 1). A chest radiograph showed right sided consolidation and pleural effusion and a convex out pouching along the left heart border (Figure 2).

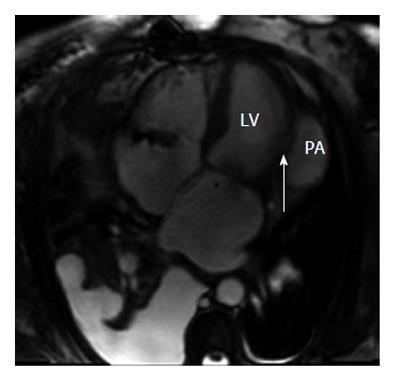

The patient was started on nitroglycerin drip but continued to have chest pain. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed dyskinesis and marked thinning of mid and basal anterior-lateral segments consistent with infarction in the distribution of the left circumflex artery. It also showed a ruptured ventricular wall with a large pericardial effusion adjacent to the dyskinetic segment. On doppler, a bidirectional shunt across the lateral left ventricle is seen, indicative of LV aneurysm (Figure 3). The width of the neck is 5.8 mm and the maximal internal diameter of the aneurysmal sac is 48 mm with the neck to sac ratio of less than 0.5 (about 0.12) which is strongly suggestive of pseudoaneurysm. Coronary angiograpy showed left anterior descending artery free of angiographic disease, left circumflex with 90% disease ostially and proximally. The right coronary artery (RCA) was 100% occluded ostially. Saphenous vein graft to RCA was patent with normal flow. Saphenous vein graft to the first obtuse marginal (OM1) with a jump graft to second obtuse marginal (OM2) were patent but there was distal disease in both the OM1 and OM2 up to 80%.

Subsequently, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were done and the diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm was confirmed (Figures 4 and 5). Intra-operatively, the patient was found to have a LV lateral pseudoaneurysm with approximately 1.5 cm diameter free wall perforation; the LV pseudoaneurysm contained a thrombus and was communicating with the LV cavity. The LV pseudoaneurysm was repaired with a bovine pericardial patch. She was discharged to a rehabilitation center on post-operative day 7. Four weeks post operatively, she was discharged from the rehabilitation center and was performing very well.

LV pseudoaneurysm also referred to as contained LV wall rupture is a rare complication that is reported in less than 0.1% of all myocardial infarction patients. It is catastrophic causing death in 48% of patients without surgical intervention[1]. LV pseudoaneurysm is a result of cardiac rupture contained by the pericardium and is characterized by the absence of myocardial tissue in its wall unlike true aneurysm which involves the full thickness of the cardiac wall.

Frances et al[2] in 1998 reviewed data from 290 patients and reported the most common etiology of LV pseudoaneurysm to be myocardial infarction followed by cardiac surgery. The risk factors for the LV pseudoaneurysms are older age, female sex, hypertension and inferior and lateral wall myocardial infarction. The common location for LV pseudoaneurysm is postero-inferior followed by postero-lateral and anterior, in contrast to true LV aneurysm which is more commonly located in the anterior and apical walls[2]. The patients with LV pseudoaneurysm usually present within 2 mo of a myocardial infarction[3].

The clinical presentation of patients with LV pseudoaneurysm is not specific and can mimic myocardial infarction or heart failure. Patients could be asymptomatic (12%) or could have persistent or recurrent chest pain (30%), shortness of breath (25%) or non-specific symptoms like dizziness or altered mental status, and 3% of the patients could have sudden death as a presenting symptom[4].

The physical examination is nonspecific with soft heart sounds, pericardial friction rub and a new systolic murmur. Electrocardiogram changes in most cases include sinus bradycardia, junctional rhythm and changes reflecting ischemia or infarction. A convexity or a mass adjacent to the cardiac silhouette can be present on the chest radiograph in more than half of the cases (Figure 2). None of these findings are specific for LV pseudoaneurysm which brings the focus to the cardiac imaging modalities.

It can be challenging to diagnose LV pseudoaneurysm with the ambiguity in its clinical presentation and the nonspecific physical findings. However, prompt diagnosis is essential as LV pseudoaneurysm is associated with a cardiac rupture risk of 30%-45%[4]. Therefore, cardiac imaging plays a very significant role in the diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm. Currently, various cardiac imaging modalities are available for diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm.

TTE has increased the number of diagnosed LV pseudoaneurysm cases. Being a noninvasive technique, TTE is routinely used for initial assessment in suspected patients as it helps in diagnosing LV pseudoaneurysm and also in determining the infarction. A ratio of < 0.5 between the width of the neck and the maximal internal diameter of the aneurysmal sac[5] or the presence of bidirectional turbulent flow through the neck by color and pulsed Doppler study[6], are suggestive of a LV pseudoaneurysm. TEE further assists in improving the accuracy of diagnosing LV pseudoaneurysm because in TTE there can be field of view limitation for visualization of the LV inferior wall.

Cardiac MRI is a non-invasive modality that enables the diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm. It is useful in identification of the pericardium, detection of thrombi, and in distinguishing between necrotic and normal myocardium. It provides morphological definition of a LV pseudoaneurysm location, extension and relation to adjacent structures. Delayed enhancement enables accurate assessment of the location and extent of the infarcted area and of viable myocardium, all of which are essential to determine optimal management. Cardiac MRI being a non invasive modality without risk of radiation exposure, has an enormous value in differentiating between LV aneurysms and LV pseudoaneurysms, with the ability to obtain cross sectional views in any plane. Cardiac MRI has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 83%[7].

Cardiac computed tomography is another non invasive imaging modality used for acquiring the three-dimensional anatomical and functional information on the myocardium and pericardium[8]. However, the limited temporal resolution, the usage of iodinated contrast and exposure of the patient to ionizing radiation, makes it less favorable.

Left ventriculography demonstrates the narrow neck connecting the ventricle to the cavity in which contrast liquid remains for several beats following the injection.Though left ventriculography is considered the gold standard modality with a diagnostic accuracy of about 85%[9], it is seldom used because of the concern for thrombus dislodgement.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, urgent surgical intervention is necessary in acute LV pseudoaneurysm[10] as the risk of rupture outweighs the risk of surgery. Small retrospective studies have shown that patients with incidental finding of chronic small LV pseudoaneurysm less than 3 cm in size[10] and patients with increased surgical risk[11] can be managed conservatively. But until large studies confirm the favorable outcomes of medical management over surgical intervention, the preferred approach would remain surgical management.

In conclusion, since it is challenging to diagnose LV pseudoaneurysm because of the ambiguity in its presentation, diagnosis in a timely manner is crucial. High clinical suspicion and early utilization of the non-invasive modalities for detection of LV pseudoaneurysm are essential to improve the outcome in these patients.

A 75-year-old female patient with history of coronary artery bypass graft and aortic valve replacement presenting with cough, shortness of breath and chest pain.

Grade 2/6 systolic murmur over the aortic area, no gallops, no rub, and no jugular venous distension. Diminished breath sounds in the mid and lower right lung fields and crackles over the left lower lung field and trace bilateral lower extremity edema.

Myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, left ventricular (LV) aneurysm, LV pseudoaneurysm, pericarditis.

White blood cell count: 13.50 k/μL, hemoglobin: 10.2 g/dL, hematocrit: 31.2%, platelets: 334 k/μL, creatinine: 0.74 mg/dL, troponin: 4.00 ng/mL, total creatinine phosphokinase: 75 U/L, creatinine kinase myocardial band: 10.4 ng/dU.

Transthoracic echocardiogram with doppler showed a bidirectional shunt across the ruptured lateral left ventricle. The width of the neck is 5.8 mm and the maximal internal diameter of the aneurysmal sac is 48 mm.

Surgical repair of LV pseudoaneurysm.

The diagnosis of LV pseudoaneurysm is challenging requiring high clinical suspicion for timely diagnosis and management.

This case report presents a rare case of pseudoaneurysm and the use of advanced imaging modalities in the diagnosis.

LV pseudoaneurysms are a rare finding mainly in patients after myocardial infarction; difficult to diagnose and are associated with a high mortality. The case report demonstrates very nicely the main diagnostic findings in this setting.

| 1. | Hoey DR, Kravitz J, Vanderbeek PB, Kelly JJ. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm causing myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:431-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Frances C, Romero A, Grady D. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:557-561. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yeo TC, Malouf JF, Reeder GS, Oh JK. Clinical characteristics and outcome in postinfarction pseudoaneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:592-595, A8. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Contuzzi R, Gatto L, Patti G, Goffredo C, D’Ambrosio A, Covino E, Chello M, Di Sciascio G. Giant left ventricular pseudoaneurysm complicating an acute myocardial infarction in patient with previous cardiac surgery: a case report. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2009;10:81-84. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gatewood RP, Nanda NC. Differentiation of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm from true aneurysm with two dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:869-878. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sutherland GR, Smyllie JH, Roelandt JR. Advantages of colour flow imaging in the diagnosis of left ventricular pseudoaneurysm. Br Heart J. 1989;61:59-64. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gill S, Rakhit DJ, Ohri SK, Harden SP. Left ventricular true and false aneurysms identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:e35-e37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ghersin E, Kerner A, Gruberg L, Bar-El Y, Abadi S, Engel A. Left ventricular pseudoaneurysm or diverticulum: differential diagnosis and dynamic evaluation by catheter left ventriculography and ECG-gated multidetector CT. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:e209-e211. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Figueras J, Cortadellas J, Domingo E, Soler-Soler J. Survival following self-limited left ventricular free wall rupture during myocardial infarction. Management differences between patients with or without pseudoaneurysm formation. Int J Cardiol. 2001;79:103-111; discussion 111-112. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Prêtre R, Linka A, Jenni R, Turina MI. Surgical treatment of acquired left ventricular pseudoaneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:553-557. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yeo TC, Malouf JF, Oh JK, Seward JB. Clinical profile and outcome in 52 patients with cardiac pseudoaneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:299-305. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewers: Kettering K, Wu CC S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ