Published online Apr 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.111

Revised: March 2, 2014

Accepted: March 13, 2014

Published online: April 16, 2014

Processing time: 185 Days and 0.1 Hours

Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor (RNFP), which presents abdominal clinical manifestations and malignant radiographic results, usually requires radical resection as the treatment. However, RNFP has been recently described as an extremely rare benign post-inflammatory lesion of a reactive nature, which typically arises from the sub-serosal layer of the digestive tract or within the surrounding mesentery in association with local injury or inflammation. In addition, a postoperative diagnosis is necessary to differentiate it from the other reactive processes of the abdomen. Furthermore, RNFP shows a good prognosis without signs of recurrence or metastasis. A 16-year-old girl presented with a 3-mo history of epigastric discomfort, and auxiliary examinations suggested a malignant tumor originating from the stomach; postoperative pathology confirmed RNFP, and after a 2-year follow-up period, the patient did not display any signs of recurrence. This case highlights the importance of preoperative pathology for surgeons who may encounter similar cases.

Core tip: Our case report describes a rare benign tumor originating from the gastrointestinal tract. To date, this lesion has been reported in 20 cases worldwide. The most significant and important insights are that these diseases possess fairly good prognosis with opposite radiographic and clinical findings. Pathologically, reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor (RNFP) was recently described arising from the sub-serosal layer or within the surrounding mesentery. However, the veracity of the pathological examination results and the etiology are still controversial. We will describe the complete diagnostic and therapeutic process of a young girl with RNFP and will retrospectively analyze the previously reported cases, particularly the microscopic and immunohistochemical characteristics.

- Citation: Yi XJ, Chen CQ, Li Y, Ma JP, Li ZX, Cai SR, He YL. Rare case of an abdominal mass: Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor of the stomach encroaching on multiple abdominal organs. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(4): 111-119

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i4/111.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i4.111

Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor (RNFP) is a recently reported lesion that may arise from the gastrointestinal tract or the mesentery. It was first described by Yantiss et al[1] in 2003. To date, 20 cases (8 cases in Czech Republic[2], 7 cases in the United States[1,3,4], 2 cases in France[5,6], and 1 case each in Australia[7], Turkey[8] and Italy[9]) have been reported in the literature. We described the first case in China. All the cases require surgical interventions with or without preoperative pathological examinations because of their typically malignant radiographic results. However, this lesion presents an encouraging prognosis during follow-up. Here we present a case in a young female patient.

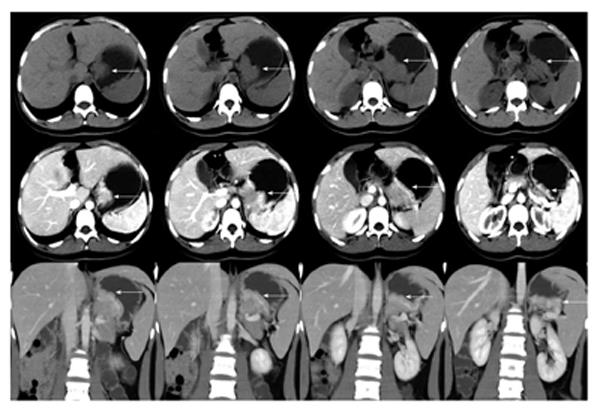

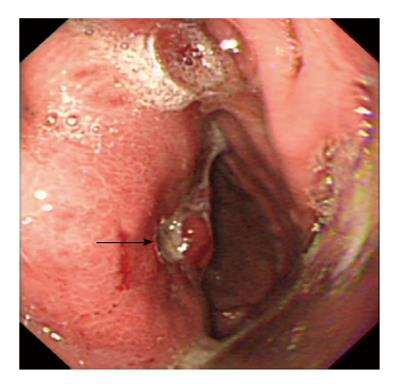

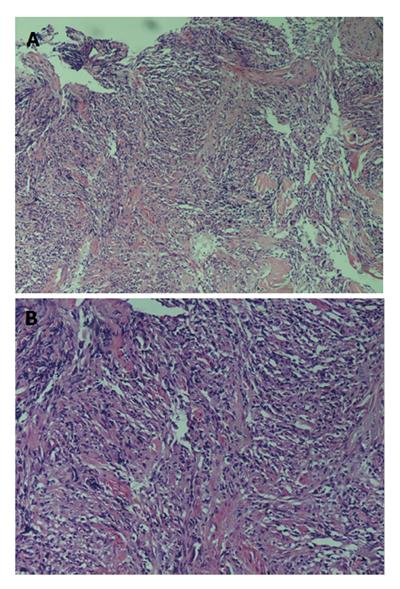

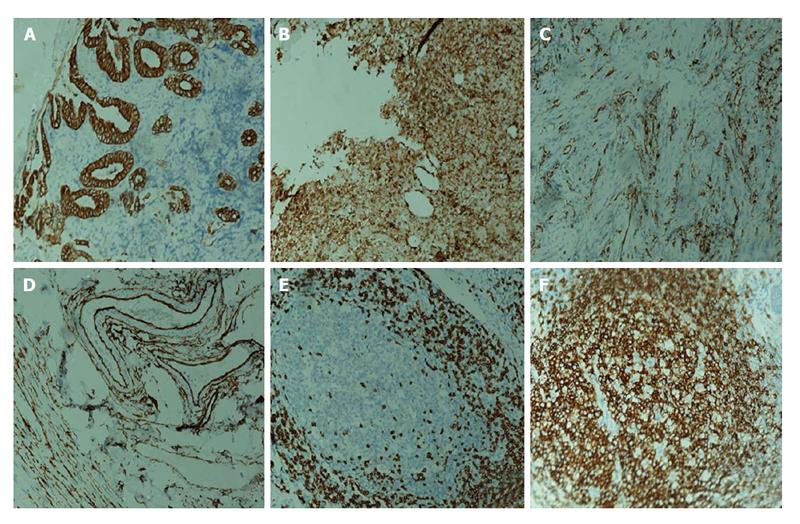

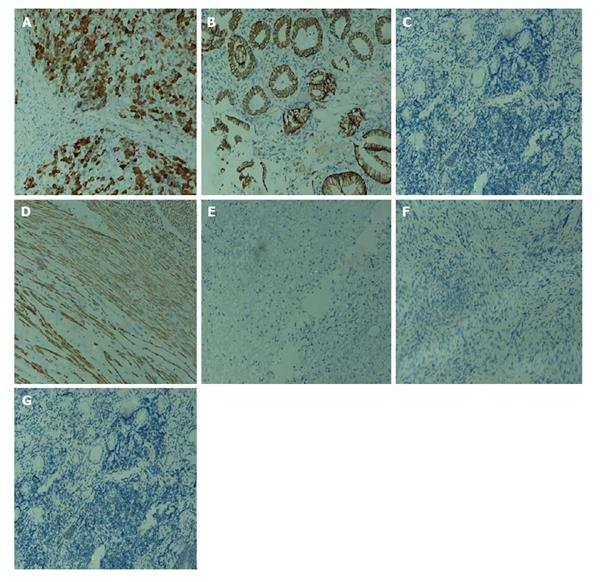

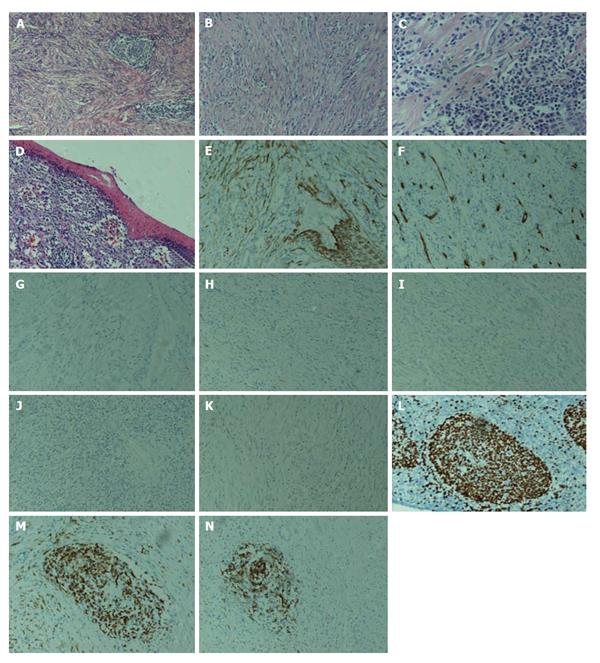

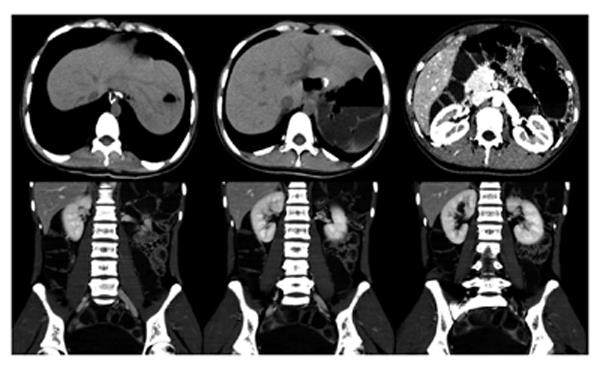

A 16-year-old girl from Jiangxi Province with no surgical history or abdominal injury history presented to a local medical institution with an approximately 3-mo history of progressive epigastric discomfort. Gastroscopy suggested a highly suspicious malignant tumor of the gastric cardia and fundus, chronic erythematosus exudative antral gastritis and a duodenal bulbar ulcer. For further treatment, the patient was admitted to our hospital. Her abdominal examination revealed light tenderness in the epigastric region. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass (5.8 cm × 3.8 cm × 7.9 cm) in the lesser curvature of the fundus attached to the left adrenal gland with obscure boundaries, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) was suspected (Figure 1). Gastroscopy revealed a protruding lesion on the back wall of the gastric cardia and fundus with a coarse surface, and an approximately 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm ulcer was located in the middle of the lesion (Figure 2). Gastroscopic pathological biopsy findings demonstrated an ulcer-forming chronic gastritis without evidence of carcinoma (Figure 3); immunohistochemically, the biopsy specimen was positive for CK and M-CEA in the glandular epithelium, positive for CD31 and CD34 in the vascular endothelium, and positive for CD3 and L26 in the small lymphocytes. Therefore, lymphoma and gastric cancer were excluded (Figure 4), and additional immunohistochemical diagnostic evidence was needed to differentiate GIST from other differential diagnoses (Figure 5). Further gastroscopic ultrasonography showed an immense mass (approximately 4.8 cm × 3.1 cm) that did not penetrate the serosa with an uneven hypoechoic appearance and blood flow on the back wall of the lesser curvature of the fundus. Approximately 6-7 lymph nodes were found next to the mass, and the largest one was 0.6 cm in size. Based on these findings, the patient was sent to the operating room with a presumptive diagnosis of malignant tumor of the fundus (GIST). Upon exploratory laparotomy, a small nodule (1.0 cm × 1.0 cm) in the lesser omentum was detected, and the main mass (approximately 8.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 5.0 cm) was located in the lesser curvature of the gastric cardia and fundus transmurally infiltrating the stomach and encroaching on the pancreatic body and tail, spleen, and left adrenal gland; several swollen perigastric lymph nodes were also visible. Based on the above findings, a total resection of the stomach, pancreatic body and tail, spleen, and left adrenal gland was performed. An esophagojejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis was used to reconstruct the digestive tract. Postoperative pathologic evaluation revealed a mass (approximately 8.0 cm × 6.0 cm) with a coarse surface transmurally infiltrating the stomach. The gross gastric specimen (15.0 cm × 11.0 cm × 5.0 cm in size) revealed a small depressed region 2.0 cm in size below the main mass. Microscopically, ulcers were detected on the mucosa; the sub-mucosa was composed of mature spindle cells embedded in a dense collagenic hyalinized stroma containing abundant infiltrative lymphocytes, plasmocytes, and hyperplastic lymphoid follicles. No mitosis, necrosis, or nuclear atypia was identified. Other sections including the pancreatic body and tail, spleen, and left adrenal gland and lymph nodes did not reveal any carcinoma tissue, and the staple line also appeared to be microscopically free of tumor. The immunohistochemistry findings of the spindle cells were as follows: actin focally (+), CD34 focally (+), CD117 (-), S-100 (-), desmin (-), DOG-1 (-), PDGFR (-), Ki-67 approximately 2% (+); the immunohistochemistry findings of the lymphocytes were as follows: CD3 (+), L26 (+). Combining the Hematoxylin Eosin (HE) stain and immunohistochemistry, the lesion was diagnosed as RNFP (Figure 6). Postoperatively, the patient’s laboratory evaluation revealed elevated white blood cells and platelets. Accordingly, antibiotics, dipyridamole, and bayaspirin were administered as symptomatic treatment. The patient did well after these interventions and was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 11. Then, 10 mo later, a follow-up CT scan examination was clear of signs of recurrence and metastatic disease (Figure 7). After more than 2 years of follow-up, the patient did not complain of any discomfort and no signs of recurrence have been found.

HE stained 4-mm slides were cut from paraffin embedded tissue that was processed with 10% buffered formalin. A panel of antibodies (Table 1) was used to evaluate the tumors for the presence of smooth muscle, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, glandular epithelium, vascular endothelium and lymphocytic classification. Several pivotal markers expressed in GISTs (CD117, CD34, DOG-1, PDGFR) and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors [anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)] were used as well.

| Antibody | Dilution | Source | Antigen retrieval |

| CK | 0.181 | Dako | Heat |

| Actin | 0.181 | Dako | Heat |

| CD34 | Working solution | Novocastra | Heat |

| CD117 | 0.181 | Dako | Heat |

| S-100 | 0.736 | Novocastra | Heat |

| Desmin | Working solution | Zsjqbio | Heat |

| DOG-1 | 0.389 | Zsjqbio | Heat |

| PDGFR | 0.181 | SANTA CRUI | Heat |

| Ki-67 | 0.181 | Zsjqbio | Heat |

| CD3 | Working solution | Zsjqbio | Heat |

| L26 | 0.736 | Dako | Heat |

| ALK | 0.111 | Dako | Heat |

| β-Catenin | 0.181 | Maixinbio | Heat |

| CD31 | Working solution | Novocastra | Heat |

| M-CEA | Working solution | Novocastra | Heat |

The first 5 RNFP cases were reported in adults by Yantiss et al[1]. The original pathological description was considered a landmark in the short history of this disease. More recent cases have been reported, and our case represents the 21st report of this lesion worldwide in the English literature.

The adult population appears to be the main target in terms of the age distribution. A total of 18 adult cases (85.7%, age range, 22-72 years) have been reported compared to 1 case in a 1-year-old boy, 2 cases in a 13-year-old girl and our case of a 16-year-old girl. The average age is 46.1 years old (male: 49.6; female: 39.1). The sexual distribution ratio is 2:1 (male to female) consisting of 14 males (66.7%) and 7 females (33.3%). Unquestionably, males are more predisposed to this disease. The leading clinical characteristics can be summarized as follows: 11 patients including our case presented with abdominal symptoms, among which 4 patients had acute abdominal pain while 3 had chronic abdominal discomfort. Past medical history revealed that 5 patients (23.8%) had a history of abdominal surgery. One patient had undergone a left hemicolectomy 17 years previously for stage pT3N0MO-IIA colon cancer according to the 7th American Joint Committee on Cancer[9]. Yantiss et al[1] reported a patient with a history of alcoholism and recurrent pancreatitis, complicated by necrotizing pancreatitis, which required multiple surgical debridements. Another patient had a history of MEN-1 syndrome and multiple abdominal surgeries, including resections of an endocrine tumor of the pancreatic tail and an adrenal adenoma 23 and 21 years previously, respectively; one patient had a history of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and resection of a duodenal gastrinoma 1 year before the development of this tumor-like mass. The fifth patient’s surgical history included a cholecystectomy some years prior for cholecystitis and an operation in 2001 for a strangulated hernia[7]. A significant abdominal medical history was noted in 9 cases (42.9%), including the following: a peptic ulcer in 3 cases (containing our case); a perforated duodenal diverticulum in a 32-year-old man; endometriosis together with ergotamine use for migraine in a 28-year-old woman; chronic bowel obstruction complicated by an external fistula in a 30-year-old woman; ileus caused by a tumor of the ileum in a 22-year-old man; and ingestion of a foreign body in 2 cases (in one case, it was an iron pin, and in the other, it was a small abscess cavity containing foreign bodies). Hence, in 14 patients (66.7%), a medical or surgical abdominal history appears to play a vital role in the development of RNFP.

In 2004, Daum et al[2] first suggested that RFNP originated from multipotent subserosal progenitor cells rather than myofibroblasts; therefore, some scholars had addressed the importance of investigating a patient’s past abdominal surgery and medical history because such conditions could more or less trigger the occurrence of these lesions’ and illustrated its reactive nature. The general findings were that these lesions represented an exuberant inflammatory response rather than a true tumor. However, our case was similar to the minority of RNFPs without a previous abdominal surgery or injury.

RNFP presented with multiple masses or, a bit more frequently, as a single mass (13 cases, 61.9%). All of the cases underwent complete resections (18 cases, 85.7%) except 3 cases in which incomplete resections were performed because of too many masses or nodules. One patient was a 71-year-old man with multiple hepatic deposits[9], and in a 28-year-old woman, numerous nodules presenting on the surface of the ovaries, appendix, the bowel mesentery, the abdominal peritoneal wall, and the omentum were detected[8]. The anatomic site of the main lesions most commonly involved the colon with the appendix (7 patients) followed by the mesentery and the small bowel (especially the terminal ileum) (7 cases each), omentum (2 cases), the peritoneal wall (3 cases), the hepatic capsule, the gastric wall, and the peripancreas (1 case each). Our case was the first to be diagnosed as RNFP transmurally infiltrating the stomach, encroaching on the pancreatic body and tail, the spleen, and the left adrenal gland. Commonly, RNFP lesions are depicted as firm and of light colors from whitish to tan or gray; rarely, calcifications are present in the lesions (3 cases, 14.3%) (Table 2).

| Ref. | Number of lesion | Size of main lesion (cm) | Morphology | Method of resection | Site of main lesion |

| 2Yantiss et al[1] | Multiple | 6.5 in diameter | Firm, tan-white | Complete resection | Mesentery of small intestine |

| Single | 4.3 in diameter | Ditto | Complete resection | Peripancreas | |

| Multiple | 5.5 in diameter | Ditto | Complete resection | Mesentery of small intestine and large bowel | |

| Multiple | 6.5 in diameter | Ditto | Incomplete resection | Mesentery of small intestine | |

| Single | 2.8 in diameter | Ditto | Complete resection | Mesentery of large bowel | |

| 3Daum et al[2] | Single | 3.0 in diameter | 1 | Complete resection | Small intestine |

| Single | 1 | White fibrous, containing an iron pin | Complete resection | Large bowel | |

| Single | 3.0 × 3.0 | Fibrous | Complete resection | Large bowel | |

| Single | 10.0 in diameter | Containing a coprolith | Complete resection | Large bowel | |

| Single | 8.0 × 3.0 | 1 | Complete resection | Small intestine | |

| Single | 8.0 in diameter | Yellow-white, elastic | Complete resection | Subserosa and mesentery of large bowel | |

| Single | 4.0 × 7.0 × 2.0 | Hard fibrous, containing minute calcifications | Complete resection | Small intestine | |

| Single | 3.0 × 4.0 × 6.0 | A small abscess cavity containing foreign bodies | Complete resection | Subserosa of large bowel | |

| Chatelain et al[5] | Single | 9.0 in diameter | Firm, white | Complete resection | Mesentery of large bowel |

| Zardawi et al[7] | Multiple | 0.5 × 2.2 | Firm, white, containing two gray cord-like structures | Complete resection | Small intestine and the omentum |

| Saglam et al[8] | Multiple | 0.6-6.0 in diameter | Firm, tan to white | Incomplete resection | The pelvic and abdominal peritoneum |

| Gauchotte et al[6] | Multiple | 1.9-2.2 in diameter | Firm, grayish white | Complete resection | Stomach |

| Yin et al[3] | Single | 2.0-3.0 in diameter4 | Tan, white, containing calcifications | Complete resection | Mesentery of small intestine |

| Virgilio et al[9] | Multiple | 6.0 × 4.0 × 3.0 | Firm, white, containing calcifications | Incomplete resection | Small intestine, hepatic capsule the left paracolic gutter |

| McAteer et al[4] | Single | 8.8 × 3.8 × 2.0 | Firm, tan-gray | Complete resection | Mesentery of small intestine |

Microscopically, all of the lesions shared the same feature consisting of a paucicellular proliferation of spindle or stellate cells embedded in a hyalinized matrix and sometimes surrounded by inflammatory cells (mostly in the form of mononuclear lymphoid cells) or lymphoid aggregates. If a lesion contains foreign bodies, dispersed giant cell granulomas are observed. Characteristically, the lesions do not show mitosis, necrosis, or nuclear atypia.

Ultra-structural examination of 3 cases by Daum et al[2] revealed spindle or stellate-shaped cells with rare intercellular junctions and irregular nuclei, prominent rough endoplasmic reticulum, sparse pinocytic vesicles, bundles of microfilaments attached to dense bodies, and focal investment by external lamina. These features were typical of myofibroblastic differentiation. In addition, genetic investigations revealed no substitutions, deletions, or insertions occurring in exon 11 of the c-kit in 7 specimens. Likewise, no deletions or insertions in part of exon 9 were observed. As above, ultra-structural analysis was performed by Yantiss et al[1] in 1 case, and the spindle or stellate-shaped cells were shown to contain abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, aggregates of filaments associating with dense bodies, which are characteristic of fibroblastic and myofibroblastic differentiation.

Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that all of the lesions stained positively for vimentin, (17/18) SMA, (8/15) CK, (10/13) MSA, except 4 cases that stained positively for CD117 reported by Yantiss et al[1] and 1 case reported by Chatelain et al[5]; most cases are negative for CD117. The vast majority of the lesions stained negatively for desmin, CD34, S-100 protein, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1. The immunohistochemical features of our case showed actin focally (+), CD34 focally (+), CD117 (-), S-100 (-), desmin (-), DOG-1 (-), PDGFR (-), Ki-67 approximately 2% (+). Thus, based on these observations, our case is consistent with a diagnosis of RNFP (Table 3).

| Ref. | Vimentin | SMA | Cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) | MSA | Desmin | S-100 | CD34 | CD117 | ALK-1 | CK5/6 | EMA | CAM5.2 | 34βE12 | CD68 | PI |

| 1Yantiss et al[1] | (+) (5/5) | (+) (3/5) | (-) (0/5) | (+) (4/5) | (+) (3/5) | (-) (0/5) | (-) (0/5) | (+) (4/5) | (-) (0/5) | (-) (0/5) | |||||

| 2Daum et al[2] | (+) | Focally (+) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | < 1.0% |

| (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 0% | |

| (+) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | 3.70% | |

| (+) | (+) | Focally (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | < 1.0% | |

| (+) | (+) | Focally (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | < 1.0% | |

| (+) | (+) | Focally (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) | 3.50% | |

| NM | Focally (+) | NM | NM | (-) | (-) | NM | (-) | (-) | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | < 1.0% | |

| (+) | Focally (+) | Focally (+) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | < 1.0% | |

| 3Chatelain et al[5] | (+) | (+) | |||||||||||||

| Zardawi et al[7] | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||

| 4Saglam et al[8] | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (+) | ||||||||||

| 5Gauchotte et al[6] | (+) | (+) | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | |||||||

| Virgilio et al[9] | (+) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | ||||||||||

| 6McAteer et al[4] | (+) | (+) | (+) | Focally (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

Importantly, RNFP must be distinguished from the other reactive processes of the abdomen [such as calcifying fibrous pseudotumor, Vanek’s tumor, retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing mesenteritis, nodular fascitis, intra-abdominal fibromatosis] and more aggressive mesenchymal tumors, such as GIST, intraabdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, and inflammatory fibrosarcoma; such a differentiation may have strict requirement for pathologists.

Of the 21 patients, almost all cases underwent complete resections (18 cases, 85.7%); incomplete resections were performed in 3 cases because of too many masses or nodules. Surgical resection is currently the definitive method in these patients, and no chemotherapy treatment has been reported. Follow-up of 11 patients was available, without signs of recurrence and metastasis regardless of the modus operandi (Table 4).

| Ref. | Gender | Age | Presenting symptoms | Medical history | Follow up |

| Yantiss et al[1] | Male | 48 | 1 | No residual disease following surgical resection (mean follow-up 16.3 mo) and one patient who had an incomplete surgical resection had stable disease at 26 mo | |

| Female | 50 | 1 | Abdominal surgical history | ||

| Male | 53 | Acute abdominal pain | 1 | ||

| Male | 57 | Acute abdominal pain | 1 | ||

| Male | 71 | 1 | Abdominal surgical history | ||

| Daum et al[2] | Male | 59 | Abdominal symptoms | 1 | 4 patients are available, without signs of recurrence and metastatic disease 5, 5, 6, and 7 yr, respectively |

| Male | 46 | 1 | |||

| Male | 1 | Abdominal symptoms | |||

| Male | 68 | 1 | |||

| Female | 30 | Abdominal symptoms | |||

| Female | 65 | 1 | |||

| Male | 22 | Abdominal symptoms | |||

| Male | 41 | 1 | |||

| Chatelain et al[5] | Male | 32 | Chronic abdominal pain | 1 | 1 |

| Zardawi et al[7] | Female | 72 | 1 | Abdominal surgical history | 1 |

| Saglam et al[8] | Female | 28 | Chronic abdominal pain | Abdominal history | 1 |

| Gauchotte et al[6] | Male | 60 | 1 | Abdominal history | No evidence of disease 4 mo later |

| Yin et al[3] | Male | 65 | Acute abdominal pain | No abdominal surgical history | 1 |

| Virgilio et al[9] | Male | 71 | 1 | Abdominal surgical history | No signs of recurrent 4 yr later |

| Mcateer et al[4] | Female | 13 | Acute abdominal pain | No abdominal surgical history | 1 |

A 16-year-old girl presented to the hospital with an approximately 3-mo history of progressive epigastric discomfort.

Approximately 3-mo history of progressive epigastric discomfort.

Gastric cancer, colon cancer, acute pancreatitis.

Laboratory tests were within normal limits.

A computed tomography scan showed a mass (5.8 cm × 3.8 cm × 7.9 cm) in the lesser curvature of the fundus attached to the left adrenal gland with obscure boundaries.

Gastroscopic pathological biopsy demonstrated chronic ulcer-forming gastritis without evidence of carcinoma; immunohistochemically, the biopsy specimen was positive for CK and M-CEA in the glandular epithelium, positive for CD31 and CD34 in the vascular endothelium, and positive for CD3 and L26 in small lymphocytes, therefore, lymphoma and gastric cancer were excluded.

A total resection of the stomach, pancreatic body and tail, spleen, and left adrenal gland was performed, and an esophagojejunal Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed to reconstruct the digestive tract.

The lesion is not very well understood and did not have predictive biomarkers to indicate reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor.

Actin, CD34, CD117, S-100, desmin, DOG-1, PDGFR, CD3 and L26 are immunohistochemical methods that are used for differentiating other tumors.

In the future, more microscopic and immunohistochemical methods should be developed, and more molecular level studies of these lesions to elucidate the etiology are needed.

This case presented in this article is well documented and interesting as it describes a rare pathology.

| 1. | Yantiss RK, Nielsen GP, Lauwers GY, Rosenberg AE. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor of the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery: a clinicopathologic study of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:532-540. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Daum O, Vanecek T, Sima R, Curik R, Zamecnik M, Yamanaka S, Mukensnabl P, Benes Z, Michal M. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumors of the gastrointestinal tract: report of 8 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:365-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chatelain D, Manaouil D, Levy P, Joly JP, Sevestre H, Regimbeau JM. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor of the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:416; author reply 417. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zardawi IM, Catterall N, Cox SA. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor of the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:276-277. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Saglam EA, Usubütün A, Kart C, Ayhan A, Küçükali T. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor involving the pelvic and abdominal cavity: a case report and review of literature. Virchows Arch. 2005;447:879-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gauchotte G, Bressenot A, Serradori T, Boissel P, Plénat F, Montagne K. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor: a first report of gastric localization and clinicopathologic review. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:1076-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yin SS, Zhang L, Cziffer-Paul A, Divino CM, Chin E. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor presenting as a small bowel obstruction. Am Surg. 2011;77:790-791. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Virgilio E, Pucci E, Pilozzi E, Mongelli S, Cavallini M, Ferri M. Reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor of the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery giving multiple hepatic deposits and associated with colon cancer. Am Surg. 2012;78:E262-E264. [PubMed] |

| 9. | McAteer J, Huaco JC, Deutsch GH, Gow KW. Torsed reactive nodular fibrous pseudotumor in an adolescent: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:795-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers: Lu YW, Tanase CP S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ