Published online Feb 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i2.42

Revised: December 23, 2013

Accepted: January 7, 2014

Published online: February 16, 2014

Processing time: 143 Days and 10.1 Hours

Malignant melanoma is a malignancy of pigment-producing cells (melanocytes) located predominantly in the skin. Nodal metastases are an adverse prognostic factor compromising long term patient survival. Therefore, accurate detection of regional nodal metastases is required for optimization of treatment. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remain the primary imaging modalities for regional staging of malignant melanoma. However, both modalities rely on size-related and morphological criteria to differentiate between benign and malignant lymph nodes, decreasing the sensitivity for detection of small metastases. Surgery is the primary mode of therapy for localized cutaneous melanoma. Patients should be followed up for metastases after surgical removal. We report here a case of inguinal lymph node enlargement with a genital vesicular lesion with a history of surgery for malignant melanoma on her thigh two years ago. CT and diffusion weighted-MRI (DW-MRI) were applied for the lymph node identification. DW-MRI revealed malignant lymph nodes due to malignant melanoma metastases correlation with pathological findings.

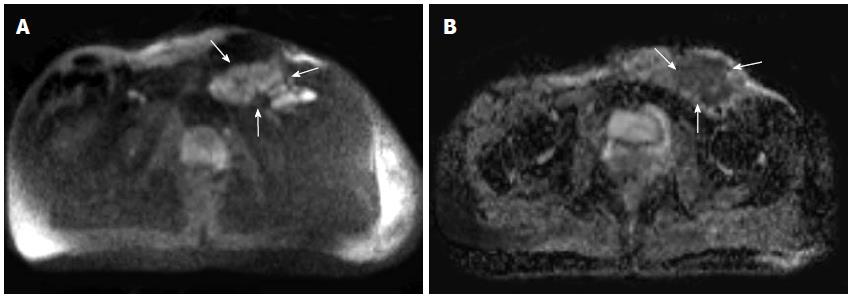

Core tip: Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) measures differences in tissue microstructure based on the random displacement of water molecules. The differences in water mobility are quantified using the apparent diffusion coefficient which has an inverse relationship with tissue cellularity. As such, the technique is able to differentiate between tumoral tissue and normal or necrotic tissue. In this paper, we present an inguinal lymph node metastasis of malignant melanoma after surgery, with DW-MRI findings.

- Citation: Bayraktutan U, Kantarci M, Pirimoglu B, Ogul H, Okur A, Gursan N. Utility of diffusion-weighted imaging in the diagnosis of inguinal lymph node metastasis with malignant melanoma. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(2): 42-44

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i2/42.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i2.42

Malignant melanoma is located predominantly in the skin but also found in the eyes, ears, gastrointestinal tract, leptomeninges and oral and genital mucous membranes. Melanoma accounts for only 4% of all skin cancers; however, it causes the greatest number of skin cancer-related deaths worldwide. Early detection of thin cutaneous melanoma is the best means of reducing mortality[1]. We present a case with inguinal lymph node enlargement with a genital vesicular lesion with a history of surgery for malignant melanoma two years ago.

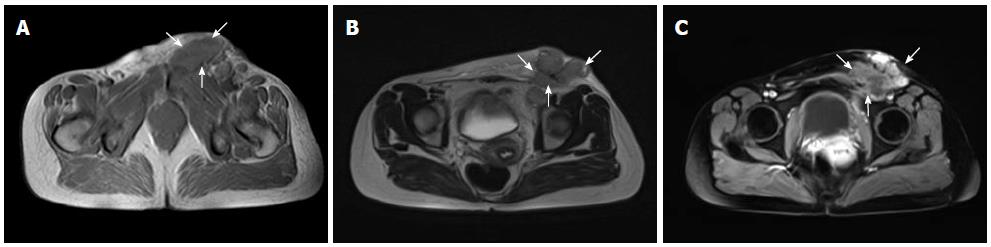

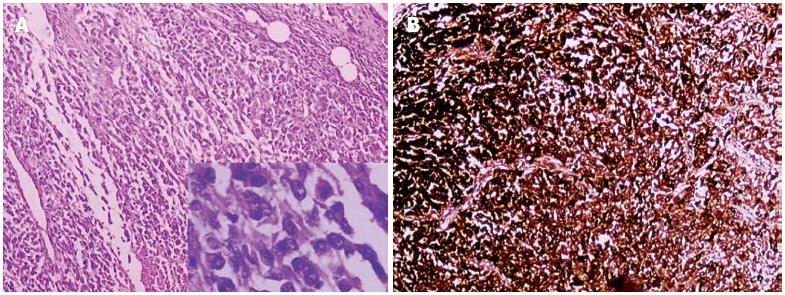

A 38-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital complaining of a mass on her left inguinal region for about 1 mo. On physical examination there was left inguinal lymph node swelling and a genital vesicular lesion. The patient had a history of malignant melanoma on her thigh 2 years ago. Computed tomography (CT) scans showed inguinal conglomerated lymph node enlargement that may be inflammatory due to a genital lesion or malignant melanoma metastases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also showed inguinal conglomerated lymph node enlargement (Figure 1). Diffusion-weighted MRI revealed reduced apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values in these lymph nodes consistent with malignancy (Figure 2). After removal of the mass by surgery, histopathological examination showed evidence of malignant melanoma metastases (Figure 3).

Malignant melanoma arises from melanocytes, the cells that give skin its color, and can spread to nearby lymph nodes and, eventually, distant sites in the body. Approximately 50000 new cases of malignant melanoma occur in the United States every year and about 8000 people die from this most lethal form of skin cancer. If untreated, malignant melanomas can spread rapidly, sometimes causing death within months of diagnosis. However, the five year cure rate of early, superficial lesions is nearly 100%[1,2].

Melanomas can occur on mucous membranes of the mouth, genital regions and anus. Sun-exposed areas are at higher risk than shielded areas. Although melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, and some types are more likely to be found in some areas than others, women tend to develop more melanomas on their legs, while men’s arise more frequently on the torso[2].

Risk factors for malignant melanoma are sun exposure, white race, first degree relatives with a history of melanoma (may increase one’s risk by up to eight times), personal history of previous melanoma, dysplastic nevus syndrome, large congenital melanocytic nevi, lentigo maligna (“Hutchinson’s freckle”), history of other non-melanoma skin cancers, immunosuppression and higher numbers of melanocytic nevi (moles)[3].

Surgical removal of melanomas that have not metastasized or penetrated to deeper layers of skin is often curative. Metastatic disease is generally inoperable. Lymph node dissection, immunotherapy, vaccine therapy, chemotherapy and hyperthermia are among the modalities used to treat metastases[4]. Current the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines do not recommend surveillance laboratory or imaging studies for asymptomatic patients with stage IA, IB and IIA melanoma (i.e., tumors ≤ 4 mm depth). Imaging studies (chest radiograph, CT and/or positron emission tomography-CT) should be obtained as clinically indicated for confirmation of suspected metastasis or to delineate the extent of disease and may be considered to screen for recurrent/metastatic disease in patients with stage IIB-IV disease, although this latter recommendation remains controversial. Routine laboratory or radiological imaging in asymptomatic melanoma patients of any stage is not recommended after 5 years of follow-up[5].

CT and MRI facilitate detection of lymph nodes; however, both modalities rely on size-related and morphological criteria to differentiate between benign and malignant lymph nodes. Diffusion-weighted imaging measures differences in tissue microstructure based on the random displacement of water molecules. The magnitude of water molecule movement is expressed as an ADC value. Its usefulness in the diagnosis of malignant tumors has gained interest. The technique is able to differentiate between tumoral tissue and normal or necrotic tissue[5,6]. The improved nodal identification may aid treatment planning and further nodal characterization[7]. In conclusion, DWI is recommended for evaluation of lymph node metastasis in patients with malignant melanoma.

A 38-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with complaint of a mass on her left inguinal region for about 1 mo ago.

On physical examination there were left inguinal lymph node swelling and a genital vesicular lesion.

Computed tomography (CT) scans showed inguinal conglomerated lymph node enlargement, may be inflammatory due to genital lesion or malignant melanoma metastases.

CT and diffusion weighted-magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) were applied for the lymph node identification, DW-MRI revealed malignant lymph nodes due to malignant melanoma metastases correlation with pathological findings.

DWI is recommended for evaluation of lymph node metastasis in patients with malignant melanoma.

Presentation and readability of the manuscript is good, the paper is brief, concise, the text is clear and easily comprehensible, adequately describes the course of the disease, its diagnostics and treatment of the patient.

P- Reviewers: Kimyai-Asadi A, Negosanti L, Zamurovic M S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7953] [Cited by in RCA: 8113] [Article Influence: 477.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13286] [Cited by in RCA: 13559] [Article Influence: 645.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Friedman GD, Tekawa IS. Association of basal cell skin cancers with other cancers (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:891-897. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Demierre MF, Nathanson L. Chemoprevention of melanoma: an unexplored strategy. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Balch CM. 2010 TNM staging system for cutaneous melanoma...and beyond. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1475-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vandecaveye V, De Keyzer F, Hermans R. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in neck lymph adenopathy. Cancer Imaging. 2008;8:173-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mir N, Sohaib SA, Collins D, Koh DM. Fusion of high b-value diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted MR images improves identification of lymph nodes in the pelvis. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2010;54:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |