Published online Oct 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i10.552

Revised: July 11, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Published online: October 16, 2014

Processing time: 188 Days and 3.3 Hours

AIM: To identify standards, how entities of dental status are assessed and reported from full-arch radiographs of adults.

METHODS: A PubMed (Medline) search was performed in November 2011. Literature had to report at least one out of four defined entities using radiographs: number of teeth or implants; caries, fillings or restorations; root-canal fillings and apical health; alveolar bone level. Cohorts included to the study had to be of adult age. Methods of radiographic assessment were noted and checked for the later mode of report in text, tables or diagrams. For comparability, the encountered mode of report was operationalized to a logical expression.

RESULTS: Thirty-seven out of 199 articles were evaluated via full-text review. Only one article reported all four entities. Eight articles reported at the maximum 3 comparable entities. However, comparability is impeded because of the usage of absolute or relative frequency, mean or median values as well as grouping. Furthermore the methods of assessment were different or not described sufficiently. Consequently, established sum scores turned out to be highly questionable, too. The amount of missing data within all studies remained unclear. It is even so remissed to mention supernumerary and aplased teeth as well as the count of third molars.

CONCLUSION: Data about dental findings from radiographs is, if at all possible, only comparable with serious limitations. A standardization of both, assessing and reporting entities of dental status from radiographs is missing and has to be established within a report guideline.

Core tip: Full mouth dental radiographs are in worldwide daily use and contain various informations about dental and oral health of adult patients. This is why it is often used for epidemiologic research or to augment clinical data. But, when reported, data is presented in multifarious ways. Thus no or only little comparison of research outcome is possible. Existing standards of evaluation and reporting should be fixed in a reporting guideline regarding: number of teeth and implants; caries, fillings and restorations; root-canal fillings and apical health; alveolar bone level. Application of sum scores turned out to be very questionable.

- Citation: Huettig F, Axmann D. Reporting of dental status from full-arch radiographs: Descriptive analysis and methodological aspects. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(10): 552-564

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i10/552.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i10.552

Beside diagnosis support, X-rays are an established method to follow up treatments with surrogate characteristics, such as: bone loss in implantology, periodontology and maxillo-facial surgery, or apical flare up and loss of teeth in endodontology, or caries prevalence in operative dentistry.

Moreover, it is used for assessment of skeletal changes focussing orthodontic or temporo-mandibular-disorders. It is even possible to find approaches of forensic medicine, i.e., for non-invasive age determination via orthopantomograms.

The quality of panoramic radiographs has enhanced during the last years. Namely their sensitivity and specifity to diagnose findings, as mentioned before, is considered to be satisfying. Problems of underestimation are discussed commonly. Nevertheless, determining oral health by radiographic presentable dimensions of the dental status is possible. That is why panoramic radiographs are often used for epidemiologic and retrospective analysis of dental status and oral health respectively. Recently, a review subsumed the competence and application of panoramic radiographs for epidemiologic studies of oral health[1]. However, it remains uncertain, whether standards are established to report radiographic findings which describe dental status or oral health data in general. No results, neither in Pubmed/Medline, EQUATOR-Network (http://www.equator-network.com) or Cochrane Library could be identified searching a relevant guideline. Therefore, this systematic review was launched, to find out, which approaches are commonly used, to assess and report the entities: decay, missing, restorative, endodontic and periodontal status as surrogate dimensions of oral health (Table 1).

| Focused entities | Subject of clinical dentistry | Surrogate of oral health |

| Alveolar bone loss, furcation and vertical bony defects | Periodontology, implantology | Periodontitis/inflammation, risk of tooth loss |

| Fillings/inlays | Operative dentistry | Oral hygiene, caries, decay, risk for massive fillings/partial crowns |

| Massive filling/partial crown | Operative dentistry, prosthodontics | Risk of root canal treatment, risk for crown-treatment |

| Crowns and fixed dental prosthesis/pontics | Prosthodontics, periodontology | Massive decay (even of healthy teeth), risen risk for caries and endodontic problems, risk for bone loss and fracture (missing teeth), missing teeth |

| Root canal filling and root posts | Operative dentistry, endodontology, prosthodontics | High number of life events of intervention, risk of tooth loss by fracture/inflammation, need for crown |

| Apical lesion | Endodontology, oral surgery | High risk of tooth loss, poor root canal treatment, inflammation |

| Missing teeth | Prosthodontics, implantology | High number of life events of interventions, former inflammations, trauma, hypodontia, malocclussion |

| Implants | Periodontology, prosthodontics | Missing teeth, higher risk for inflammation (periimplantitis), occlusal rehabilitation |

| Edentoulism | Prosthodontics, oral surgery | High number of life events, no further risk of odontogenic inflammation (caries, periodontitis, apical lesions) |

A Medline/PubMed search was performed for articles reporting findings from full arch radiographs, focused on oral health and dental status of adults. This search was conducted in November 2011. No time limit was set. Panoramic X-ray or a full-mouth radiographic survey with periapical radiographs of all remaining teeth were definied as “Full arch radiograph”. In the following, the term “radiograph” will be only used in this sense.

To find and include such papers the following search-string was constructed stepwise and applied finally as: (“radiographic study” or “panoramic”) and (“oral health” or “dental status” or “dental health” or “dentition”) not (children OR review OR edentulous)

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were set for a full text review of findings: All peer-reviewed reports with dental findings obtained from full arch radiographs are included, even if there had been additional clinical examination or patient chart reviews. These reports had to focus on at least one surrogate of “dental status” or “oral health” (Table 1), whereas reports handling edentulous or partially edentulous patients were disregarded.

Only articles written in English were included. Studied cohorts had to be of adult age, respectively the mean age had to be at least 18 years.

If it was not determinable in the abstract, which kind of radiography was applied or which variables of dental status were reported, the article was included to full-text review.

Excluded was all literature handling radiometric issues only [i.e., bone density, cephalometric angles of jaw and joint, subjected to soft-tissues (carotis, lymphal-nodes)] or focusing on specific teeth/tooth types only (such as caries in third molars) as well as anthropologic analysis. Articles were also excluded, if they turned out to report on the basis of bitewing radiographs or specific single radiographs to fulfill their objective.

Every previously included paper was reviewed towards the report of at least one out of the following eight variables (Ia-IV), which reflect the surrogates listed in Table 1. If inclusion was validated, information about: (1) Bibliography and focus of study; (2) Number of patients studied and country of origin; (3) Number and kind of radiographs studied was noted first. Then the materials and method section (MMS) and results were checked for the following 8 variables of interest: Ia: remaining/missing teeth (also included in DMFT/S); Ib: implants or implant-loss; IIa: fillings (also included in DMFT/S); IIb: decay/caries (also included in DMFT/S); IIc: restorations (i.e., crowns); IIIa: root canal treatment; IIIb: apical status; IV: alveolar bone level on teeth or implants.

These variables were recorded by their mode of report. Further statistical analyses applied to these variables within the articles were disregarded, due to the different focus of the studies. Regarding the application of these variables, it was noted if additional arrangements, exclusion or inclusion criteria towards the report were mentioned by the authors. For example: how to handle the “third molars”, supernumerary teeth or teeth not depicted clearly on radiographs.

If a variable was mentioned in the section “methods” but not reported, it was mentioned not reported “(NR)”. If a variable was not mentioned within the method section, it was noted as not defined “(ND)”. Furthermore it was recorded, if the authors applied a special method of evaluation and how it was described or whom they cited. A “?” was assigned to indicate an assumption by the reviewers throughout the data, whenever there was no clear statement within the context of the article. For longitudinal studies, the different comparisons between the dates of results were not considered, as far as no other way of report was applied. Information about removable dentures had been neglected, because these are generally not allowed to be seen on radiographs at all. If results of a study or cohort were published twice, first, the longer observation period and, secondly, the higher impact factor in year of publication gave favor for inclusion.

The report of variables I to IV was reduced to a simple logic expression. Every expression, shown in Table 2, can be translated with the following “keys-words” and abbreviations: “ND” or “NR” indicates “not defined” or “not reported”.

| Ref. | Number of X- rays evaluated | Ia: Number of teeth | IIa: Fillings | IIb: Caries | IIc: Restorations | IIIa: RCF | IIIb: apF | IV: ABL |

| Helenius-Hietala et al[17] 2011b | 212 | N[r-teeth](mean,SD)[pat] | ND | N[pat] (mean)/G[spec] | ND | ND | NR | mm(mean,SD)/pat; meanABL[pat]/G[spec]; N[teeth+G[ABL]] (mean,SD)/G[spec] |

| Yoshihara et al[40] 2011a | 177 | N[r-teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec,gender] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Andersen et al[28] 2011b | 52 | N[r-teeth](mean,SD, median,Q)[pat]/G(age) | ND | ND | ND | Combined: N[teeth](mean,SD,median,Q)[pat]/G[age]; N[teeth](F,%)[toothtype]/G[age] | ND | |

| Seppänen et al[18] 2011b | 84 | N[r-teeth](median,rg) [pat] | ND | N[pat](F,%)[all pat], G[spec] | ND | ND | ND | N[pat](F)[ND]/G[spec] |

| Willershausen et al[9] 2011d | 2374? | N[r-teeth](mean?)/ G[age,spec], N[m-teeth](mean)/G[age] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec], N[pat](%)/G[age] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec], N[pat](%)/G[age] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec]; N[pat](%)/G[age] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec], N[pat](%)/G[age] | ND | ND |

| Kirkevang et al[22] 2009b | 470 | N[r-teeth](median,rg)[pat]/G[age] | N[teeth+1,2,3 surfaces](median,range)[pat]/G[age,toothtype] | N[teeth](median,rg)[pat]/G[age,tooth-type] | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Saeves et al[10] 2009d | 93 | N[m-teeth](mean)[pat]/G[age,spec] | N[teeth](mean)[pat]/G[age,spec] | ND | “Some” | N[teeth](%)[all teeth]; N[pat](F)[spec] | ND | ND |

| Tarkkila et al[13] 2008b | 161 | N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | Combined with clinical examination: N[DMFT,DT,FT](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | ND | NR | NR | ND | |

| Buhlin et al[49] 2007b | 51 | N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec,all] | N[DMFS](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec,all]; N[DMFT](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec,all] | ND | ND | N[lesions](F,%)[pat]/G[spec] | N[pat](F,%)/G[grade] | |

| Nalçaci et al[26] 2007d | 190 | N[r-,m-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,tooth-type] | N[teeth](median,SD)[pat]/G[gender,all] | N[teeth](median,SD) [pat]/G[gender,all] | N[FPD](F,%)/G[gender,jaw] N[teeth](SD,median)[pat] | N[teeth](median,SD) [pat]/G[gender,all] | N[teeth](median,SD)[pat]/G[gender,all] | N[pat](median, SD)[ND ABL]/G[gender] |

| Huumonen et al[3] 2007b | 95 | N[m-teeth](F)/G[spec] | ND | N[teeth](F)/G[spec]; N[findings?](F)/G[spec] | ND | N[teeth](F)/G[spec] | N[teeth](F)/G[spec]; | N[pat](F)/G[spec] |

| Jansson et al[36] 2006c | 191? | N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/ G[spec] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | N[pat](F)/G[spec] |

| Tabrizi et al[11] 2006c | 20 | N[r-teeth] (F,mean,SD)[pat] | N[DMFS,DMFT](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | Included to DMFT? | ND | ND | ABL(mean)[pat] | |

| Skudutyte-Rysstad et al[30] 2006d | 146 | ND | ND | ND | ND | N[pat+tooth](F,%)[all]; N[pat]/N[teeth](F); N[teeth](F,%)/G[spec] | N[pat+tooth](F,%)[all]; N[teeth](F)[grade]; N[pat]/N[teeth](F); N[teeth](F,%)[all]/G[spec] | ND |

| Peltola et al[31] 2006a | 307 | NR via DMFT | NR via DMFT N[pat](F)[DMFT = 0]/G[spec] | N[lesions](mean,SD) [pat]/G[spec] | ND | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | N[lesions](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | NR |

| Ma et al[2] 2005a | 1232 | N[pat+m-teeth](%)/G[tooth-type]; N[m-teeth](%)[tooth-type] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Olze et al[14] 2005d | 275 | NR | NR | NR | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Cabrera et al[4] 2005c | 1417 | N[pat](F)/G[m-teeth,spec] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Rosenquist et al[5] 2005b | 452 | N[pat](F)[G[m-teeth]/G[spec] | N[pat](F)[G[m-teeth]/G(spec) | ND | N[pat](F)[teeth]/G[spec] | N[pat](F)[grade]/G(spec) | ||

| Montebugnoli et al[44] 2004c | 113 | NR via pantomography index | ND | NR via Pantomography index | ND | ND | NR | NR |

| Abou-Raya et al[46] 2002a | 50 | N[pat+m-teeth](%)/G[spec] | ND | NR via Pantomography index | ND | ND | NR via pantomography index | NR via pantomography index |

| Enberg et al[21] 2001a | 137? | N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,age,spec] | ND | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,age,spec] | ND | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,age,spec] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,age,spec] | N[teeth](F,%)[pat]/G[gender,age-group,spec] |

| Närhi et al[6] 2000a | 396 | N[pat+r-teeth]; N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,jaw,spec] | ND | N[teeth]; N[teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,spec] | ND | absN[teeth], N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,spec] | N[teeth], N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[gender,jaw,spec] | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat,grade]/G[gender, spec] |

| Aartman et al[43] 1999a | 211 | N[r-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/ G[spec] | ND | N[teeth](mean,SD) [pat]/G[spec] | ND | N[teeth](mean,SD)[pat]/G[spec] | ND | ND |

| Taylor et al[38] 1998b | 362 | N[r-teeth?](median)/G[spec] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | N[pat](F,%)[grades]/G[spec, age-group]; |

| Grau et al[48] 1997c | 126 | NR via pantomography index | ND | NR via pantomography index | ND | NR via pantomography index | NR via pantomography index | NR via pantomography index |

| Peltola et al[19] 1993c | 990? | N[pat](%)[DMFT = 0] | N[DMF](mean,SD)[pat]/G[age] | N[teeth](mean,SD,rg)[pat] | ND | N[pat](%) | N[pat](%) | N[pat+ND G[ABL]](F,%) |

| Hakeberg et al[33] 1993c | 180 | N[m-teeth] (mean,SD,rg)[pat]/G[spec,gender,age] | N[surfaces](mean,SD,rg)[pat]/G[spec, gender,age] | N[surfaces](mean,SD,rg) [pat]/G[spec,gender,age] | ND | N[m-teeth] (mean,SD,rg)[pat]/G[spec,gender,age] | N[lesions](mean,SD,rg)[pat]/G[spec,gender,age] | N[lesions](mean)[pat]/G[grade,spec] |

| Corbet et al[24] 1992b | 165 | N[m-teeth] (mean,SD)[pat]/G[age]; N[m-teeth](%)[FDI] | ND | ND | N[pontics,cantilever,crowns](%)[FDI]; N[FPD](%)[units]; N[units,retainers](mean,SD)[all FPD] | ND | ND | ND |

| Lindqvist et al[15] 1989d | 50 | N[r-teeth](mean,rg)[pat] | N[pat+”seriously decayed teeth”](F,%) | N[teeth,pat](F); N[“Inadequate” RCF](F,%) | N[pat](F)/G[lesions] | N[pat](F,%)/ G[“periodontits”]; N[pat?](F)[spec] | ||

| Stermer Beyer-Olsen et al[37] 1989c | 141 | ND | ND | ND | ND | N[teeth](F), N[pat](F,%) | N[teeth,RCF-teeth](F), N[pat](F,%) | N[pat](F,%) |

| Grover et al[7] 1982a | 5000 | N[pat](F,%)/G[m-teeth] | Combined for all carious as N[findings,pat](F,%) | ND | N[findings,pat](F,%) | N[pat+G[periodontits]](F,%) | ||

| Langland et al[16] 1980b | 2921 | ND | ND | N[pat+lesion?](F,%) | N[pat+FPD](F,%) | N[pat+tooth](F,%) | N[pat+lesion?](F,%) | N[pat+G[periodontits]](F,%) |

| Meister et al[25] 1977b | 5783 | ND | ND | ND | N[pat+FPD](F,%) | ND | N[findings](F,%) | N[pat+G[periodontits]](%) |

| Pelton et al[20] 1973d | 200 | ND | ND | N[findings](F)/G[jaw,spec] | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Christen et al[27] 1967b | 1338 | ND | ND | ND | “Many ill fitting crowns” | ND | N[pat+tooth](F) | N[pat+”gross periodontits”](F,%) |

| Lilly et al[8] 1967d | 1285 | N[pat](F,%)/G[r-teeth] | ND | ND | ND | N[teeth](F)/G[tooth-type]; N[pat,canals](F) | N[teeth](F)G[spec] | ND |

“N” = “number”; “[]” = “of/in”; “()” = “expressed as”; “/” = “by presenting values”; “,” = “and”; “+” = “with”; “G” = “in group (s)”; “F” = frequency, “%” = percentage, “SD” = standard deviation, “Q” = quartiles, “rg” = range, “al” = “all patients/teeth/surfaces”, “tot” = “total”, “pat” = “patient(s)”, “grades” = “declared graduation or scaling of measurements”, “FDP” = “fixed dental prosthesis”.

Variable I refers to “r” = remaining, “m” = missing or “f” = lost/failed teeth. Variables II-IV always refer to affected patients, teeth, lesions, surfaces or sites. Following groups were standardized: age, gender, jaw, tooth-type, age-group, grades (of a previously defined classification).

If authors introduce special groupings (i.e., diseased/ healthy, baseline/follow-up and so on), it was abbreviated “spec” for “special”. This was mandatory due to the different outcome-variables of the studies.

For dental terms following abbreviations were used: “ABL” = “alveolar bone level/loss”, “apH” = “apical health”, “RCF” = “root canal filled”, “FDI” = “FDI-tooth code”, “FDP” = “fixed dental prosthesis”.

Two examples of this operationalization: The following expression in the column “IIb Caries/Decay”: “N[surface](mean, SD)[pat]/G[age, gender]” is translated to “The number of carious surfaces is expressed as mean and standard deviation in a patient, by presenting values in groups of age and gender”.

Another exemplary expression in the column “IIIa RCT” is “N[pat + teeth](F)” translated to “Number of patients with affected teeth is expressed as frequency”.

All included papers were ordered according to their objective. Bibliography as well as number and origin of patients were described by frequency distributions. To discuss the consistency, the findings were subsumed for all papers towards each entity of interest. Therefore cited methods of radiographic evaluation were full-text reviewed, as far as these were written in English or German and obtainable via library services.

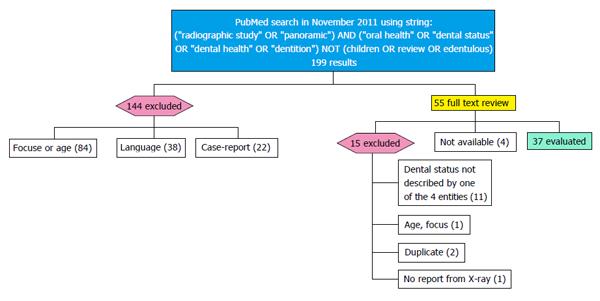

Following Figure 1, thirty-seven studies were evaluated and can be found in Table 2.

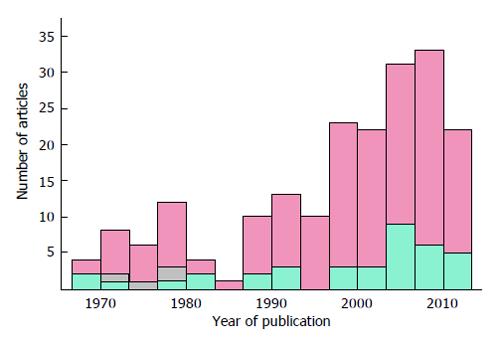

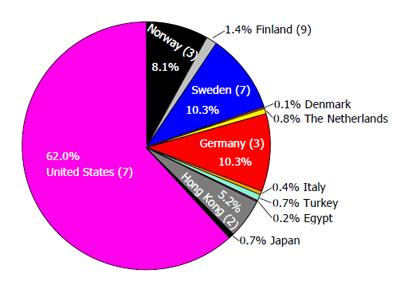

The years of publication of all results are shown in Figure 2. In whole 27447 (median = 191) X-rays have been evaluated and reported within 37 studies including 27772 (median = 215) patients. Figure 3 shows the shares of patients towards their origin. Ninety-four percent of the patients studied were from United States and Europe.

For nine journals no Impact Factor (IF) was noted at Journal Citation Report (JCR) of “Web of Knowledge” (http://www.webofknowledge.com). The 5-year IF in 2010 of all JCR-listed and evaluated journals was median = 2.23, range: 0.89-6.39, SD = 1.16. So the included articles represent an extract of high ranked journals, regarding an average IF of about 1.3 (median = 1.2, mean = 1.5) for Dental Journals listed in the JCR in 2011.

All modes of report are shown-according to the scheme of operationalization-in Table 2. The following subheadings subsume these findings and focus on the methodic of radiographic assessment.

Thirty/37 (81%) of all studies reported remaining and/or missing teeth. Four articles intended a report of these values within their material and method section, but did not so. Beside mean-and median values, two artificial approaches were found: Ma et al[2] reported the prevalence of missing tooth types (first molars). Other authors gave the number of absolute frequency of missing teeth within their studied cohort[3]. In addition to this the following groupings were found: “< 10 missing teeth”[4], “0, 1-5, 6-14, 15-20, > 20 missing teeth”[5], “1-7, 8-20, 21-32 teeth”[6], “1-2, 3-5, 6-9, 10-14, 15-20, 21-27 missing teeth”[7], “0, 1-11, 21-12, 22-27, 28-31, 32”[8].

This approach of grouping allowed the authors mentioned above to report only the “number of patients” within their established groups. Before 1990 absolute frequencies were reported more frequently. Due to the variety of dentition, especially existence of 3rd molars, the problem of report is thoroughly discussed below.

Only 3 articles considered and reported dental implants. That is why this column is not shown in Table 2. The modes of report were: “N[pat + implants](%)/G[age]”[9], “N[implants](F)[all pat]/G[spec]”[3] and worded “some”[10].

Due to the clinical DMFT-index decayed (carious) and filled (restored) teeth are often pooled and mixed up. Six authors did so-three out of these using the DMFT/DMFS-Index[11-13]. Overall 19 out of 37 papers mentioned to evaluate “carious problem”, “-lesions”, “-teeth” or “defective teeth”. One did not report their announced findings[14] and two remained unclear[15,16]. Four authors got more specific towards their assessment by mentioning the following criteria: “deep caries cavities”[17], “carious pulpal exposure lesions”[18], “lesions clearly perforating the enamel and clear radiolucencies under old fillings were recorded. Enamel caries was excluded”[19], “gross carious lesions ¡ in posterior teeth”[7].

Pelton et al[20] classified caries lesions within a reliability study of panoramic and periapical radiographs as “C1: radiographically viewed that involved the enamel, but did not penetrate the dentin; C2: ¡ involved the enamel and the dentin, but not the pulp; C3: ¡ said to involve the pulp”.

Two other authors explained more concrete: “Caries was judged to be present in the radiograph when a clearly defined reduction in mineral content of the proximal, occlusal, and/or restored surfaces was evident”[6], and “(Caries was) present when the lesion reached the dentin proximally or occlusally or was found at restored surfaces”[21].

Kirkevang et al[22] used a method published by Wenzel[23] described as follows: “A surface was assessed as having a caries lesion if a radiolucency, exhibiting the shape of a caries lesion and observed at a caries-susceptible site”, and augmented with “extended into dentine; radiolucencies confined to the enamel were ignored”.

In the same article Kirkevang et al[22] gave concrete information about fillings: “Registrations were performed on mesial, distal and occlusal or incisal surfaces. Fillings in pits and fissures in oral and buccal surfaces were not registered”.

Tabrizi et al[11] stated “Restorations and dental caries were also calculated for each participant”, but owes the data by presenting only DMFT-values.

Reporting is also structured by using absolute frequencies of patients with “lesions”[18,19], or “affected teeth” in all patients[3]. In addition to this, following groupings were found: “0, < 5, > 5 defective teeth”[5], “0, 1-2, ≥ 3 carious lesions”[19]. Restorations were reported six times[9,10,16,24-26], but 2 articles did insufficiently[10,27]. Within three out of seven articles restorations, fillings and decay were merged[5,11,15].

Identification of root canal filled teeth was taken for granted in 15 out of the 18 papers. Within 3 papers it was clarified in more detail within the MMS as “ongoing or completed root canal treatment, ¡, pulp amputation”, “teeth with pulp amputation, endodontic fillings, or both”[3,6,21]. One article merged root canal fillings and apical health[28].

Seventeen further articles focused on apical health. The periapical index (PAI) by Orstavik et al[29] was used for diagnosis of periapical health by only three authors, who regarded the PAI-scores 3-5 as positive finding[3,28,30].

For Peltola et al[31] “A radiolucency measuring > 2 mm in the apical bone was considered to be an apical rarefaction”. Nalçaci et al[26] cited Soikkonen et al[32] method: “A periapical lesion, interpreted as apical periodontitis, was recorded if there was a clearly discernible local widening of the apical periodontal membrane space”. But, this approach is not described within this referred citation (handling edentulous patients at all). Hakeberg et al[33] divided “Periradicular destructions ¡ into three different classes according to size; 1 = pathologically altered lamina dura and radiolucency less than 2 mm, 2 = radiolucency of 2-10 mm, 3 = radiolucency > 10 mm”[33], and set grade 2 as cut-off for affection. The earliest grading found was in Lilly et al[8] 1967: “less than 5 mm and 5-10 mm apical translucency”[8].

The remaining five articles only mentioned to evaluate “apical radiolucencies”[17], “periapical lesions”[5], without further criteria or mentioning additions like: “radicular cysts as well as sclerotic periapical lesions indicating condensing osteitis”[6,21], or “sign of osteolysis”[12].

The most various methods in assessment and reporting were found for alveolar bone level.

Metric measurements were used by five authors[6,7,17,21,33]. In addition to this following groupings were found: “≥ 6 mm, ≥ 4 mm”[17], “> 1-3 mm, > 3-6 mm, > 6 mm”[6], “< 2 mm, 2-4 mm, > 4 mm”[33]. “< 4 mm = moderate periodontitis, > 4 mm = severe periodontits”[7].

To relativize metric measures the following formula for alveolar bone loss is used: “total bone height divided by total root length [the distance from the radiographic apex to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ)] multiplied by 100.”, and applied i.e., by Tabrizi et al[11].

Rosenquist[5,12] decided to use a modified criterion of Lindhe[34]: “< 1/3 of the root length, > 1/3 of the root length, and horizontal loss supporting tissues, > 1/3 of the root length, angular bony defects and/or furcation involvement” which is similar to Nyman et al[35] cited by Tabrizi et al[11]. Two authors used a relative root length, but went for an overall approach and added a criterion for “diseased”via their amount of findings: “≥ 30% of the sites with ≥ 1/3 bone loss”[36] and “including one or more teeth”[37].

Semiquantitative approaches were found specified: “classified as extension to: (1) to the coronal third of the root; (2) the middle third of the root; and (3) the apical third of the root”[18,21]. Graduations apart from thirds exist also: i.e., as an ordinal scale with five grades: “0%, 1%-24%, 25%-49%, 50%-74%, or ≥ 75%”[38] or with only one cut-off point as: “one-fourth or more of the normal bone height”[37].

A direct measurement of ABL-percentages was developed by Schei et al[39] and used by only one author[38].

For two authors “A healthy horizontal bone level was considered to be 2 mm”[21,31]. Huumonen et al[3] graded into “(1) No bone loss, bone level within 2-3 mm of the cemento-enamel junction area; (2) Slight bone loss, bone level at the cervical third of theroots; and (3) Moderate to advanced bone loss, bone level between the middle third of the roots at or beyond the apex”[3]. Slightly different graduation-starting out the same with level 0-Nalçaci et al[26] continues: “(1) Moderate bone loss, bone level at the middle third of the roots; (2) Advanced bone loss, bone level at the apical third of the roots; and (3) Severe bone loss, bone level at or beyond the apex”, but did not mentioned a cut-off. So it remains unclear (ND) what the reported “horizontal bone loss” is intended to be.

In three cases the results were presented with previously not defined expressions like “periodontal problem”[18] or undefined graduations like “Slight marginal bone loss ¡ and vertical bone loss”[19]. The definition lacks what exactly is supposed to mean “affected” in this context. Likewise less helpful is a more historical graduation we came over: “If considerable bone loss was seen, this was called ‘gross periodontal disease’. If there was pronounced ‘arclike’ bone loss limited to the molar and incisor regions, this was designated as periodontosis”[25].

One methodical article on forensics was coping with the calculation of DMFT and DFT-Index. They stated within their material and method section to grade ABL of 2nd premolars towards the criteria “0, less than half of first third, up to third of root, more than a third”. But the findings were not reported at all[14].

The diversity of assessments and report modes is found to be alarming. The applied search strategy covers only a small, but high-ranked, sample of articles handling radiographic findings. It has to be assumed, that diagnosis and report of the entities studied here are not standardized at all, as it is for clinical dental status, namely the DMFT-, CPITN-, PI-, or BOP-Index for example.

In the following, each above mentioned and studied entity is discussed critically towards assessment and report. Further consequences are subsumed.

The method to identify teeth from a radiograph is quite simple. Not so the communication of amounts and values.

Commonly, every time when the descriptive level of absolute frequencies (i.e., number of affected patients) is not used, the calculation has to be relative to a standardized data-set (i.e., all patients studied, all patients with root canal treatment). It gets even more complicated, if the complete dentition is handled as an entity: When median-or mean values are used, the calculation base has to be clear. For the first: including the third molars to the calculation, or not? For the second: how to handle missing or supernumerary teeth? For the third: are edentulous patients excluded[17,40], or included to the calculation-or have there been other selection criteria like “at least 15 remaining own teeth”[9]?

Unfortunately this was not clear for 9 out of the 37 studied papers. Twenty-three included, 4 excluded, the third molars for evaluation. Two articles presented both approaches. Due to the variety of third molars dental history (retention, extraction) it make sense-similar to DMFT Index-to exclude these, if these are not primary focus of a study. Please follow the subheading “report of values” below, where more inherent details are addressed.

Against the backdrop of costly dental implants as a routine therapy after about 40 years now, their presence in oral status should be reported. Their number can give not only important dental input, but also ideas towards the financial background of an individual patient, a group, a whole cohort or even the social system.

The detection of carious lesions within radiographs is discussed and researched by operative dentistry, foremost. Searching “detecting caries and X-ray”via Pubmed/Medline results around 100 findings. The definitions used by the authors studied herein are inconsistent. This is why a clear statement which definition can be used as a gold standard to assess a tooth as affected by caries, would be favorable. We found the approach of Pelton and Bethart the most reproducible[20].

As fillings are made from radiopaque resin, cement, compomer, or metal, these can be easily seen on radiographs. If a restoration material is only slightly radiopaque, like silicate ceramic, the used adhesive composite or luting cements is clearly visible. However, the size of restorations can only be guessed, due to the 2-dimensional projection. But, the amount of decay could be derived from the ratio of filling and remaining coronal tooth substance.

These remarks are valid for fixed restorations (crowns, pontics) too. For all of these 3 findings, the mode of report as a comparable number and the report of missing values has to be standardized.

Root canal fillings can be recognized just as easily as a tooth or restoration itself can be, because radiopaque materials are used around the world very commonly. Two authors judged the quality of root canal fillings[3,30]. If the quality or length of root canal fillings should be regarded or not, remains to be discussed by endodontologist. Works about the potential already exist[41]. Furthermore the existence of root canal posts has to be taken into account. Some of these are either not radiolucent (Fiber-posts) or radiopaque and due to their form not possible to distinct from a perfect root canal filling.

Regarding the reporting mode as frequency or percentage is same as discussed for missing/remaining teeth. Furthermore reporting authors should care about the problem that the number of teeth is easier to compare than the number of roots or even root canals. Moreover the values of root canal treatments should be reported separately from apical affection(s) of a tooth or root.

Beside the controversy of detection capability with periapical and panoramic radiographs (augmented with the problem: digital vs analog), the key point is to diagnose the affection in awareness of healthy variations-without a clinical examination. This is analog to the detection of caries. The method of the PAI by Orstavik et al[29] is a good example for standardization and should be used more often. This 5-grade assessment tool is based on standardized pictures. It might be most reliable if used with a cut-off at Grade 3.

Confusing is the usage of “lesion” or “finding” in contrast to “affected tooth”, because i.e., a lower first molar may have 2 apical or carious lesions (mesial and distal), but is only 1 affected tooth. As for the above-mentioned root-canal fillings, at this point of time no consensus could be found. But, we found one possibility for clarification: “For multi-rooted teeth, the root presenting the highest PAI-score and the quality of the corresponding root filling was used”[30].

The “radiographic alveolar bone loss” is one classical research dimension of periodontology and implantology. Thereby it has been of interest for ages-expressed in hundreds of publications. Thus radiographic assessment of this entity is just as many-faceted. Two general approaches could be identified: metric measuring and proportions of bone height towards root length. The latter might be the better choice due to the variety of root length by anatomy and radiographic projection. Moreover, approaches including the age dependence of bone loss are described[42].

Beside bone level, furcation and vertical defects might be taken into account, too. The authors do not want to judge, which way is the best. But, even if a standard can be found in the future, also the cut off values for healthy and affected shall be defined by the authorities (see caption “grading and cut-offs”). Until then, the authors find the relative approach coping with the “first third of the root”, described by Nyman et al[35], the most reliable.

Depiction problems of X-rays may lead to missing values, because it is not always possible to state a finding (i.e., the vertical alveolar bone height by overlapped projection of two teeth, carious lesion at a filling by a “burn out” artifact). Only 5 papers mentioned depiction problems right in their material and methods section as follows: “If the image of the permanent teeth was blurred, supplementary digital intraoral radiographs were taken of these teeth”[28], “For areas poorly visible in the panoramic radiograph, intraoral radiographs were made”[6,26,37], “A tooth was judged as non-measurable if the CEJ or bone crest could not be identified properly because of overlapping caries or restorations. In cases where any one of the dental or bony landmarks could not be identified on one aspect (mesial or distal), the tooth was excluded”[11]. Projection artifacts may also lead to misinterpretation, which is mostly ruled out by the use of 2 examiners and/or reliability assurance. Such problems were solved differently: “In case of disagreement between the observers, their mean is used in the calculation”[43].

“Only panoramic radiographs that displayed the whole dentition without asymmetry, distortion or error in patient positioning were included”[2], “The radiographs were assessed twice, the first time by each dentist separately and next time by all in cooperation”[10].

One article announced within materials and method section: “Missing values were registered with suitable so-called ‘missing values”[9], but-it was true for all articles above mentioned, these values were not reported.

One of the articles revealed depiction problems while studying the X-rays and stated: “A total of 54 teeth, most often maxillary pre-molars, were excluded”[11].

Discussions about sensitivity and specifity of panoramic radiographs were only anecdotal, not concrete. Montebugnoli et al[44] dropped an important sentence, which was unfortunately not discussed further or towards their findings: “Other factors that could affect the outcomes include differences in the way of measuring ¡ dental status (the measures used to assess the oral status seem to be related to the strength and significance of the associations reported)”[44].

Beside this, Langland et al[16] mentioned within their comparative study in 1980: “Discrepancies in the percentages of periodontal disease may be attributed to variance in the classification of each disease entity each year ¡.”[16] and also Grover et al[7] did so in 1982: “Several discrepancies in findings ¡ explained by variance ¡ in diagnostic methods”. One author explicitly complained about the absence of guidelines and stated: “We found it difficult to clearly define what a short root was and how to define early obliteration of the pulp. There are no guidelines in the literature, which defined what is a short root, and what is obliteration. For that reason it was difficult to compare our data with earlier studies”[10].

In summary, it has to be pointed out again, that panoramic radiographs can be regarded as sufficient diagnosis instrument. During the past 5 years digital imaging made great strides. But, sufficient comprehensive data about quality progress is not published yet. Nonetheless, the assessment of dental findings within a radiograph is restricted by anatomical deviations of oral structures, such as dislocation or rotation of teeth. That implies missing data are common in radiographic based studies-especially for alveolar bone loss, apical health and caries. The option of an “indiscernible/unclear” criteria will reduce bias since firstly, no accidental attribution as “affected” or “healthy” have to take place, secondly an idea about overall image quality is given.

Such missing values may be handled statistically, but have to be reported and how these were regarded in calculation.

The number of remaining and missing teeth is reported most frequently (see caption “missing/remaining teeth and implants”). But even in this case, comparability is difficult due to the different modes of reporting. 4 authors decided for the report of median-number, 16 for mean, 6 for absolute frequencies. The same utilization can be found across the other studied entities: caries, root-canal-filled teeth, apical lesions and even alveolar bone level.

For the report of frequencies the use of median values can be assigned as the better choice due to its lower susceptibility towards extreme single values and the non-normal distribution of remaining and missing teeth in patients. To clarify the distribution of data we recommend the report of both: mean and medium value, augmented with SD, range and quartiles.

A grouping of age, findings, measures are often necessary for further analyses, especially to calculate odd-ratios or only to compare such “self-made” groups. Grouping with a cut-off allows additionally to report absolute and relative frequencies of teeth or patients, instead of mean or median values. Examples for the last mentioned would be “1-10 missing teeth” or “< 20 remaining teeth”. Especially the rationales behind the cut-offs points are questionable. Sometimes these are set following previous analysis of the same sample, such as: “Each group comprised one-third of the dentate subjects in the baseline study”[6], or “Each dental index was dichotomized at the mean value”[44]. It can also be empirical reasons as: “The cut-off point (< 45 and > 45 years) was selected in accordance with the introduction of a new social-security law”[21]. However, cut-off points for “healthy” and “diseased” varied, especially if diagnosis of alveolar bone height and apical lesions are dichotomized for analyses, graphic art and report.

With such intervention to data, these are not universally valid anymore. Further comparability is hindered, if the crude data are not available from the paper.

Three authors reported DMFT-values[11-13]. One team reported only the number of patients (one time as percentage, one time as an absolute frequency) with a DMFT value of zero[19,31]. The DMFT would be helpful for a comparison with existing epidemiological data, but it hinders to extract missing/remaining teeth if only given as a sum score. If not separated by the author, no more information can be extracted from the DMFT; the DMFS is even worse. Furthermore alveolar bone level and apical health are not covered within this (exclusively) clinical index.

Within our review other indices could be found: six authors cited Mattila et al[45]: “Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction” and their sum score of a “Total Dental Index” or “Pantomographic Index”[6,12,18,46]. This is also cited as panoramic tomography score, which is “the sum of radiolucent periapical lesions, third-degree caries lesions, vertical bone pockets, radiolucent lesions in furcation areas[47]” and was applied by Montebugnoli et al[44]. Even if published and cited in high-ranked journals, we found this system neither comprehensible in development nor validated for multipurpose application. Its focus is both: infective oral lesions in a combination of oral and radiographic evaluation as well as from radiographic assessment itself. Furthermore the description of index does not contain either methods of oral nor radiographic assessment for its entities. Despite of this fact, the sum of total dental index (TDI) can reach values “between zero and 10”[45]. Nevertheless, the scale of this cited index varies between publication due to modification by the authors: “0-14”[48], “0-8”[49], “0-10”[18,50], 0-15[6]. Seppänen et al[18] used a classification of the sum scores “good, moderate and poor” which was not established by Mattila et al[45] 1989 as cited in this very article. Montebugnoli et al[44] decided to dicromize “each dental index ¡ at the mean value”. Buhlin et al[49] separated the index according to the statement “TDI of 0 or 1 are considered to have good oral health and those with TDI 4-8 have poor”. Especially these inconstancies left this tool highly questionable. However, further investigation is needed for a concluding evaluation of this approach. Beside, and discussed for the DMFT, a sum score-with such complexity of terms-might not be useful for report. Foremost because, the values of each contained entity are not given to the reader and for future comparison.

This report is only based on articles indexed at PubMed/Medline. The variety of applied approaches was expected to grow if further databases (i.e., EMBASE or MEDPILOT) are searched. Although this might harden the presented conclusion, it would not rise the informative content of this report.

Detailed information about type of X-ray and films used as well as acts of calibration of examiners was not included to this review. We took into account, that journal reviewers have already checked the applied intervention and found these appropriate. Furthermore, the widespread use of dental radiographs implies standardization on a reasonable level and quality. Findings in adults were favored, due to the variety of radiographic studies and dentition in children and adolescents. The variety of the mixed dentition is in fact a problem of standardization. The authors are aware that for every entity studied within this review, hundreds of other articles exist and there might be even standards scientists agree on. But, this can only be figured out by further systematic reviews-one for each entity and a final harmonization in a reporting guideline. Such a general guideline would support the authors preparing their studies and manuscripts as well as the scientists to compare data.

Only one article covered all entities studied in this review[26]. Nevertheless, all researches would have been enabled to report all these entities. Evidently it is often not of interest to report about i.e., alveolar bone loss while presenting results about the prevalence of apical lesions. Nonetheless, such data would contrast and illustrate findings by thorough information about the studied cohort. More accompanied information could be conveyed about dental status of studied subjects. Thus, comparability and multi-variate analyses would be simplified generally. The authors think it would be worthwhile to have an easy reporting system of all entities. Today’s possibilities to provide such data digital via online publication would enable authors and publishers to share data without expensive printed pages.

There are established but not generally accepted and enforced standards to assess and report findings from radiographic surveys. Thereby comparability of published findings is only possible with chief limitations. There is need to agree on standardized assessment and diagnosis first, and about the mode of report secondly. An easy and validated multi-term report-system of dental status would allow a widespread application, especially for dental public health and epidemiology. In consequence: there is need for a reporting guideline.

Reporting standards are necessary to compare research outcomes especially in medical science. Full-mouth radiographic surveys allow information about the dental status. These are: number of teeth, caries, fillings/restorations, root canal treatments/filling, apical health and alveolar bone loss. But findings have to be evaluated and reported in such a way, that a comparison between published results is possible. There is no reporting guideline, yet. Which mode of report could be proper is neither finally discussed nor published. The paper shows shortcommings in current acquisition and presentation of data, hereinafter it recommends suitable methodical approaches.

Dental radiology, epidemiology, research methodology in dentistry and medical statistics for oral health variables.

Only 8 out of 37 scientifically papers are at the maximum comparable towards 3 out of 7 entities of dental status. Evaluation of radiographs differ is widely. Reporting with statistical tools like mean and median or grouping and dichotomization did not allow further comparison, due to a lack of raw data. Also sum scores or indices like Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) impede comparability of data. Thus no standard could be identified. Besides, missing values are underreported.

A guideline of standards for evaluation, report and cut-off points is needed. So far it can be advised, that: (1) depicting problems and resulting missing values are reported; (2) it must be stated, if third molars are included or not when reporting the number of missing or remaining teeth; (3) implants should be taken into account; (4) sum scores are only present with crude data of the study. In case of DMFT the decayed teeth, missing teeth, filled teeth and decayed and filled teeth should be given separately, too; (5) apical health should be evaluated with a validated tool preferably the Peri-Apical-Index; (6) alveolar bone loss should be evaluated and reported in exact percentage or “in thirds” (Lindhe) not in absolute millimeters; (7) all distributions of data are presented with mean and medium value, augmented with SD, range and quartiles; and (8) the reader is given the rational for grouping or a cut-off point if data is dichotomized.

“Full-arch radiographs” are radiographs taken mostly in dental office and depicting all teeth (including the complete root) of a human dentition. Mostly a so called “panoramic radiograph” is taken; but also a survey with intraoral radiographs can be applied. “Apical health” describes the situation around the tip of the tooth root inside the bone of the jaw. This area might be retreat for bacteria causing a painless infection, which is relevant for systemic health and inflammation parameters. Such infections can be detected by radiographs. “Alveolar bone loss” describes the loss of jaw bone around teeth. The amout of lost bone correlates with the infection of tissues around teeth, which is a multifactorial disease promoted by bacteria. As seen in the radiograph the occurrence of a a so called “periodontitis” (inflammation of the gums) can be anticipated by the loss of bone. “DMFT” is the World Health Organization-standard to report a clinically assessed dental status. It is namely the sum of Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth in a dentition. “Reporting guideline” is a standardization for scientific reporting of findings. Today many such guideline exists in Medicine (http://www.equator-network.com).

It is a well organized and written paper.

| 1. | Choi JW. Assessment of panoramic radiography as a national oral examination tool: review of the literature. Imaging Sci Dent. 2011;41:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ma EC, Mok WH, Islam MS, Li TK, MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Patterns of tooth loss in young adult Hong Kong Chinese patients in 1983 and 1998. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005;71:473. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Huumonen S, Sipilä K, Zitting P, Raustia AM. Panoramic findings in 34-year-old subjects with facial pain and pain-free controls. J Oral Rehabil. 2007;34:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cabrera C, Hakeberg M, Ahlqwist M, Wedel H, Björkelund C, Bengtsson C, Lissner L. Can the relation between tooth loss and chronic disease be explained by socio-economic status? A 24-year follow-up from the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:229-236. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rosenquist K. Risk factors in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2005;1-66. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Närhi TO, Leinonen K, Wolf J, Ainamo A. Longitudinal radiological study of the oral health parameters in an elderly Finnish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:119-124. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Grover PS, Carpenter WM, Allen GW. Panographic survey of US Army recruits: analysis of dental health status. Mil Med. 1982;147:1059-1061. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lilly GE, Steiner M, Alling CC, Tiecke RW. Oral health of dentists: analysis of panoramic radiographs. J Oral Med. 1967;22:23-29. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Willershausen B, Witzel S, Schuster S, Kasaj A. Influence of gender and social factors on oral health, treatment degree and choice of dental restorative materials in patients from a dental school. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saeves R, Lande Wekre L, Ambjørnsen E, Axelsson S, Nordgarden H, Storhaug K. Oral findings in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tabrizi F, Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Klinge B. Oral health of monozygotic twins with and without coronary heart disease: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:220-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Buhlin K, Bárány P, Heimbürger O, Stenvinkel P, Gustafsson A. Oral health and pro-inflammatory status in end-stage renal disease patients. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5:235-244. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Tarkkila L, Furuholm J, Tiitinen A, Meurman JH. Oral health in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women from baseline to 2 years of follow-up with reference to hormone replacement therapy. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12:271-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Olze A, Mahlow A, Schmidt S, Wernecke KD, Geserick G, Schmeling A. Combined determination of selected radiological and morphological variables relevant for dental age estimation of young adults. Homo. 2005;56:133-140. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lindqvist C, Söderholm AL, Slätis P. Dental X-ray status of patients admitted for total hip replacement. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1989;85:211-215. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Langland OE, Langlais RP, Morris CR, Preece JW. Panoramic radiographic survey of dentists participating in ADA health screening programs: 1976, 1977, and 1978. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;101:279-282. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Helenius-Hietala J, Meurman JH, Höckerstedt K, Lindqvist C, Isoniemi H. Effect of the aetiology and severity of liver disease on oral health and dental treatment prior to transplantation. Transpl Int. 2012;25:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Seppänen L, Lemberg KK, Lauhio A, Lindqvist C, Rautemaa R. Is dental treatment of an infected tooth a risk factor for locally invasive spread of infection? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:986-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peltola JS. A panoramatomographic study of the teeth and jaws of Finnish university students. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:36-39. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pelton WJ, Bethart H. Student dental health program of the University of Alabama in Birmingham. X. The value of panoramic radiographs. Ala J Med Sci. 1973;10:21-25. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Enberg N, Wolf J, Ainamo A, Alho H, Heinälä P, Lenander-Lumikari M. Dental diseases and loss of teeth in a group of Finnish alcoholics: a radiological study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:341-347. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kirkevang LL, Vaeth M, Wenzel A. Prevalence and incidence of caries lesions in relation to placement and replacement of fillings: a longitudinal observational radiographic study of an adult Danish population. Caries Res. 2009;43:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wenzel A. Dental caries. In White SC, Pharoah MJ (eds): Oral Radiology. Principles and Interpretation, 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby 2009; 270-281. |

| 24. | Corbet EF, Holmgren CJ, Pang SK. Use of shell crowns in Hong Kong dental hospital attenders. J Oral Rehabil. 1992;19:137-143. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Meister F, Simpson J, Davies EE. Oral health of airmen: analysis of panoramic radiographic and Polaroid photographic survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 1977;94:335-339. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nalçaci R, Erdemir EO, Baran I. Evaluation of the oral health status of the people aged 65 years and over living in near rural district of Middle Anatolia, Turkey. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Christen AG, Meffert RM, Cornyn J, Tiecke RW. Oral health of dentists: analysis of panoramic radiographic survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 1967;75:1167-1168. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Andersen MG, Beck-Nielsen SS, Haubek D, Hintze H, Gjørup H, Poulsen S. Periapical and endodontic status of permanent teeth in patients with hypophosphatemic rickets. J Oral Rehabil. 2012;39:144-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Orstavik D, Kerekes K, Eriksen HM. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:20-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Eriksen HM. Endodontic status amongst 35-year-old Oslo citizens and changes over a 30-year period. Int Endod J. 2006;39:637-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Peltola JS, Ventä I, Haahtela S, Lakoma A, Ylipaavalniemi P, Turtola L. Dental and oral radiographic findings in first-year university students in 1982 and 2002 in Helsinki, Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Soikkonen K, Ainamo A, Wolf J, Xie Q, Tilvis R, Valvanne J, Erkinjuntti T. Radiographic findings in the jaws of clinically edentulous old people living at home in Helsinki, Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 1994;52:229-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Gröndahl HG. A radiographic study of dental health in adult patients with dental anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:27-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lindhe J. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. Copenhagen: Munksgaard 1998; . |

| 35. | Nyman S, Lindhe J. Examination of patients with periodontal disease. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. Copenhagen: Munksgaard 2003; 403-413. |

| 36. | Jansson H, Lindholm E, Lindh C, Groop L, Bratthall G. Type 2 diabetes and risk for periodontal disease: a role for dental health awareness. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:408-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Stermer Beyer-Olsen EM, Bjertness E, Eriksen HM, Hansen BF. Comparison of oral radiographic findings among 35-year-old Oslo citizens in 1973 and 1984. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:68-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Taylor GW, Burt BA, Becker MP, Genco RJ, Shlossman M, Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and alveolar bone loss progression over 2 years. J Periodontol. 1998;69:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Schei O, Waerhaug J, Lövdal A, Arno A. Alveolar bone loss as related to oral hygiene and age. J Periodontol. 1959;30:7-16. |

| 40. | Yoshihara A, Deguchi T, Miyazaki H. Relationship between bone fragility of the mandibular inferior cortex and tooth loss related to periodontal disease in older people. Community Dent Health. 2011;28:165-169. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Eriksen HM, Berset GP, Hansen BF, Bjertness E. Changes in endodontic status 1973-1993 among 35-year-olds in Oslo, Norway. Int Endod J. 1995;28:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hardt CR, Gröndahl K, Lekholm U, Wennström JL. Outcome of implant therapy in relation to experienced loss of periodontal bone support: a retrospective 5- year study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Aartman IH, de Jongh A, Makkes PC, Hoogstraten J. Treatment modalities in a dental fear clinic and the relation with general psychopathology and oral health variables. Br Dent J. 1999;186:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Montebugnoli L, Servidio D, Miaton RA, Prati C, Tricoci P, Melloni C. Poor oral health is associated with coronary heart disease and elevated systemic inflammatory and haemostatic factors. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:25-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, Jungell PS, Isoluoma M, Hietaniemi K, Jokinen MJ. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Abou-Raya S, Naeem A, Abou-El KH, El BS. Coronary artery disease and periodontal disease: is there a link? Angiology. 2002;53:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Mattila KJ, Asikainen S, Wolf J, Jousimies-Somer H, Valtonen V, Nieminen M. Age, dental infections, and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 2000;79:756-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Grau AJ, Buggle F, Ziegler C, Schwarz W, Meuser J, Tasman AJ, Bühler A, Benesch C, Becher H, Hacke W. Association between acute cerebrovascular ischemia and chronic and recurrent infection. Stroke. 1997;28:1724-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Ahnve S, Janszky I, Tabrizi F, Klinge B. Oral health in women with coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Abou-Raya S, Abou-Raya A, Naim A, Abuelkheir H. Rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease and coronary artery disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewer: Arısan V, Kamburoglu K S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ