INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder primarily that affects approximately 0.5%-1.0% of adults worldwide[1]. Its impact extends far beyond the musculoskeletal system, since evidence links RA with interstitial lung disease (ILD) and even with metabolic derangements such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)[2].

Large epidemiological series estimate that approximately 6% to 10% of RA patients meet criteria for clinically significant ILD[3]. Several studies suggest that patients who present these conditions simultaneously have higher mortality rates, with the death risk increasing by almost 400% in some cohorts[4,5]. Moreover, RA-ILD has been associated with an increased healthcare utilization and costs as this group of patients present higher inpatient admissions, longer length of stay and greater resource consumption[6]. In parallel, some studies propose that a higher-than-average prevalence of T2DM, obesity, and other metabolic disorders in some cohorts of patients with RA, being that a study observed an almost 25% higher risk for individuals with RA developing diabetes mellitus compared to non-RA controls[7-9].

Taken together, these observations suggest a previously poor-recognized intersection between RA, ILD, and T2DM, with few studies addressing this topic. Among them, the study by Sutton et al[10], published in the World Journal of Clinical Cases, stands out as the largest population-based study ever conducted on the subject, including observing an almost 2-fold increase risk of patients with T2DM and RA developing ILD when compared to patients with RA and without T2DM (odds ratio = 2.02; 95% confidence interval: 1.84-2.22). Thus, these editorial aims to examine the aforementioned article to highlight its strengths, draw attention to the mechanistic, epidemiological, and clinical aspects presented in the topic, and encourage future research on the subject.

METABOLIC-PULMONARY AXIS IN RA

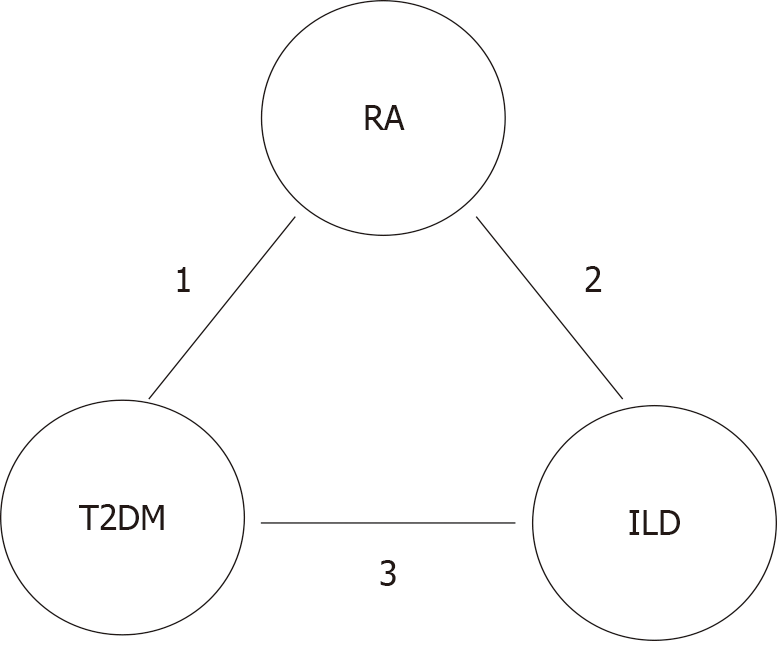

RA-ILD appears to arise from a confluence of local lung injury and systemic autoimmunity[3,4,11]. In this case, the occurrence of inhaled exposures (notably cigarette smoke) could affect genetically susceptible individuals (such as carriers of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-DRB1 and mucin 5B) promoting persistent epithelial stress of the airways, with consequent local inflammatory response, increased profibrotic mediators, reactive oxygen species and inflammasome signaling that may produce the histological and radiological patterns of interstitial pneumonia or nonspecific interstitial pneumonia[3,5,11-13]. These processes could be amplified by systemic cytokine storms characteristic of RA that not only sustain synovial inflammation but also potentiate pulmonary fibroproliferation and matrix remodeling[11,12,14]. These same chronic markers of pro-inflammation also may cause metabolic disorders, insofar as they induce serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins, impair phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B signaling in adipocytes and myocytes, and promote lipolysis with ectopic lipid deposition - producing peripheral insulin resistance[14,15]. Furthermore, they alter intracellular molecular pathways, causing epigenetic changes and mitochondrial dysfunctions that generate a chronic “metainflammatory” state[13-15]. In an organism affected by the chronic pro-inflammatory state of RA, there is a potentiation of nod-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activation with a consequent increase in circulating profibrotic cytokines, creating a vicious cycle of fibrosis in epithelial regions such as the lung, cellular dysfunction such as that of pancreatic beta cells, and even greater inflammation[9,11-13]. Simultaneously, chronic hyperglycemia could lead to non-enzymatic glycation and the accumulation of advanced glycation end products in the pulmonary interstitium; advanced glycation end products interact not only with pneumocyte cellular receptors, which may potentiate local inflammation, but also with the pulmonary microvasculature, causing local oxidative stress and even more damage and consequent fibrosis (Figure 1)[8,12,16-18].

Figure 1 The metabolic-pulmonary-autoimmune axis linking rheumatoid arthritis, interstitial lung disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

1: Interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, hyperglycemia and advanced glycation end-products; 2: Genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures trigger pulmonary epithelial injury, autoantigen release, immune activation, inflammation and fibroblast proliferation, and fibrosis; 3: Non-enzymatic glycation, endothelial damage, activation of profibrotic mediators, systemic inflammation, and metabolic stress. RA: Rheumatoid arthritis; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; ILD: Interstitial lung disease.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The triad of metabolic dysfunction, RA, and ILD frequently manifests silently in its early stages, often delaying diagnosis and the initiation of targeted therapy[5,19]. Given the overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms and potential for mutual amplification among these conditions, integrated screening strategies may be warranted[5,6,11]. Early and concurrent detection could facilitate timely, coordinated interventions, allowing clinicians to optimize both glycemic and immunologic control, mitigate pulmonary injury, and potentially slow the progression of systemic complications[15,19]. In fact, as presented by Sutton et al[10], patients with type T2DM and (RA have an almost 2-fold increased risk of developing ILD when compared to patients with RA and without T2DM.

Therapeutic decisions in patients affected by RA, T2DM, and ILD therefore require an individualized, multidisciplinary approach, as immunomodulatory therapies, antifibrotic strategies, and metabolic interventions interact in clinically meaningful ways[15,20,21]. Systemic glucocorticoids, often used to control RA flares, can exacerbate hyperglycemia, increase infection risk, and complicate ILD management[7,16,20]. Conversely, selected disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics may reduce the risk of both diabetes and pulmonary complications by dampening systemic inflammation and modulating shared pathogenic pathways[6,7,20].

From a prognostic perspective, the coexistence of T2DM appears to further worsen outcomes in RA-ILD. Metabolic comorbidity compounds pulmonary morbidity and healthcare utilization, likely reflecting the self-perpetuating pathophysiological cycle linking systemic inflammation, hyperglycemia, and fibroblast activation, compounded by metabolic compromise of renal and cardiovascular systems[19-21]. In fact, as observed by Sutton et al[10] patients with T2DM and RA had higher rates of pulmonary hypertension and pneumothorax, while hospital stays were, on average, 0.6 days longer than in non-T2DM counterparts.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In addition to the evidence presented by Sutton et al[10], further studies in this area are urgently needed for a greater understanding of the subject. Specifically, mechanistic studies should dissect the cellular and molecular interactions linking hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and RA-induced pulmonary inflammation could contribute to elucidating not only the pathophysiological pathways involved, but also to the development of targeted therapies on it. Furthermore, the impact of glycemic control on the development, progression, and severity of RA-associated lung disease remains largely unexplored; prospective and interventional cohort studies could clarify whether optimizing glycemia and insulin sensitivity attenuates pulmonary fibrosis or delays the decline in lung function. Moreover, pharmacological nuances deserve attention as antidiabetic agents can modulate inflammatory and fibrotic pathways, while immunomodulatory therapies for RA can differentially affect both metabolism and pulmonary risk, and possible interactions between these variables should be evaluated. Ultimately, more refined subphenotyping of ILD in RA is needed, encompassing radiological patterns, histopathology, and molecular signatures, to identify the patient subgroups most susceptible to metabolic amplification of fibrosis.

CONCLUSION

The recognition of diabetes as a possible conspirator in RA-ILD redefines the frontier between rheumatology, pneumology, and endocrinology. By bridging systemic autoimmunity, metabolic dysfunction, and pulmonary fibrosis, the metabolic-pulmonary-autoimmune axis compels clinicians to adopt a more holistic perspective that transcends joint-laboratorial-radiological-focused paradigms. Perhaps it is time to expand the treat-to-target concept beyond local inflammation to include metabolic homeostasis as a therapeutic goal in the care of patients with RA, diabetes mellitus, and ILD. Consequently, studies focusing on evaluating a routine metabolic screening in RA patients with pulmonary symptoms or clinical trials assessing the impact of glycemic control on ILD progression in RA could be welcome and expand our boundaries in this field. Thus, the study by Sutton et al[10], despite its limitations, can serve as a cornerstone for redirecting medical practice to provide better care to this particular group of patients.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Gupta A, Assistant Professor, Nepal S-Editor: Zuo Q L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu J