Published online Jan 6, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.115845

Revised: December 1, 2025

Accepted: December 22, 2025

Published online: January 6, 2026

Processing time: 59 Days and 17.5 Hours

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is a common condition in both preterm and term infants characterized by either thyroid gland absence or hypofunctionality. The clinical association of refractory lactic acidosis and heart failure has rarely been observed in cases of pediatric patients with CH pathology. Here, we ex

A 33-day-old extremely premature female infant presented with tachypnea, re

This case links CH-induced heart failure with refractory lactic acidosis, urging prompt thyroid screening in affected neonates to reduce mortality.

Core Tip: This report details a critical case of congenital hypothyroidism in a preterm infant, presenting as severe heart failure and refractory lactic acidosis. The infant showed a rapid, life-saving response to levothyroxine, highlighting congenital hypothyroidism’s role as a reversible cause of cardiovascular collapse. A key novelty is the profound lactic acidosis, a rarely reported feature of neonatal hypothyroidism. This case underscores the need for high clinical suspicion and repeat screening in preterm infants with unexplained heart failure or metabolic acidosis. Our findings advance understanding of thyroid hormones’ role in cardiac metabolism and confirm that prompt treatment is vital for excellent outcomes.

- Citation: Chen HJ, Li J, Xu XM, Zhang B, Cheng BC, Shi J. Preterm heart failure and refractory lactic acidosis caused by congenital hypothyroidism: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(1): 115845

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i1/115845.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i1.115845

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disability, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 2000-3000 children[1], and an even higher rate among preterm infants[2]. Primary CH results from thyroid hormone deficiency due to thyroid gland agenesis, ectopia, or functional impairment. Its increased in

CH typically manifests with non-specific symptoms, including lethargy, feeding difficulties, prolonged jaundice, and abdominal distension, although some infants are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. The neurodevelopmental consequences of delayed diagnosis were well-established; however, the cardiovascular implications in neonates remain considerably underrecognized. In adults, hypothyroidism is closely related to heart failure and cardiac mortality[4]. However, reports of CH presenting with overt cardiovascular collapse and refractory lactic acidosis in early infancy are remarkably few. This case report details a 33-day-old preterm infant who developed severe heart failure and refractory lactic acidosis secondary to previously undiagnosed CH, demonstrating an exceptional response to levothyroxine (L-T4) replacement therapy.

A 33-day-old female infant was urgently transferred to our hospital for management of worsening respiratory distress and significant abdominal distension.

She was born prematurely at 27 weeks and 5 days of gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a healthy 31-year-old mother, with a birth weight of 950 g. Her initial neonatal course was complicated by respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation, surfactant administration, and subsequent transition to nasal continuous positive airway pressure support. She received standard prophylactic antibiotics (penicillin plus cefotaxime) for 48 hours in accordance with the expert consensus guidelines for neonatal sepsis[5], as well as intravenous caffeine citrate. Enteral feeding with breast milk was initiated on postnatal day 2. On day 18, her clinical condition deteriorated markedly, with the emergence of recurrent apneic episodes, decreased responsiveness, and progressive abdominal distension. Suspected late-onset sepsis prompted treatment with a 14-day course of meropenem, although blood cultures ultimately returned negative. By day 33, some clinical improvement was noted; however, the abdominal distension and respiratory distress persisted despite no radiological evidence of necrotizing enterocolitis.

The patient was a neonate with a medical history identical to that of the present case.

Her mother had received a complete course of antenatal corticosteroids, and her prenatal examination showed no significant abnormalities. Her parents had no genetic or family history.

On admission, her physical examination revealed a poorly responsive infant with pallor and scattered ecchymosis. She exhibited severe respiratory distress with tachypnea (67 breaths/minute) and prominent intercostal, subxiphoid, and subcostal retractions. Cardiovascular examination revealed distant heart sounds with a continuous murmur audible along the left sternal border. Pulmonary auscultation revealed bilateral scattered rhonchi and moist rales. Abdominal examination showed significant distension with hepatomegaly palpable 3 cm below the right costal margin.

Initial laboratory evaluation revealed the following: White blood cell count, 3.4 × 109/L; neutrophils, 1.05 × 109/L; hemoglobin, 69 g/L. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe metabolic acidosis (pH 7.204, bicarbonate 10.7 mmol/L) and a critically elevated lactate level (23 mmol/L). Myocardial enzymes were significantly elevated, with mild-to-mod

| Blood index (unit) | Before treatment | After treatment | Reference range |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 3959.67 | 13.26 | (0-100) |

| cTnI (μg/L) | 0.484 | 0.047 | (0-0.06) |

| CK-MB (μg/L) | 77.67 | 8.85 | (0-5) |

| CK (U/L) | 1039 | 89 | (39-192) |

| Ammonia (μmol/L) | 99.9 | 34.5 | (10-47) |

| Pyruvate (μmol/L) | 240.7 | 79.9 | (20-100) |

| β-hydroxybutyric acid (mmol/L) | 0.78 | 0.15 | (0-0.27) |

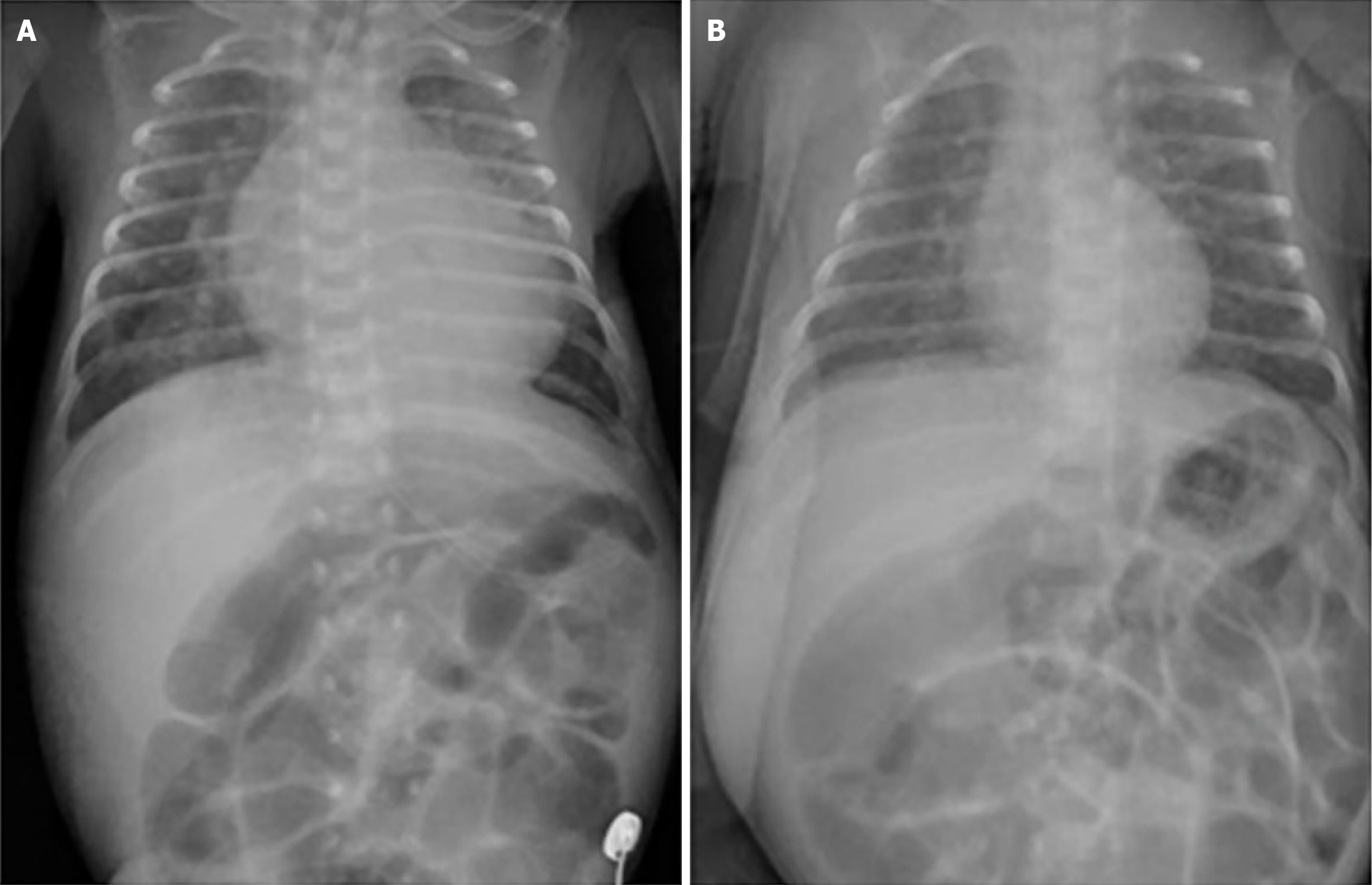

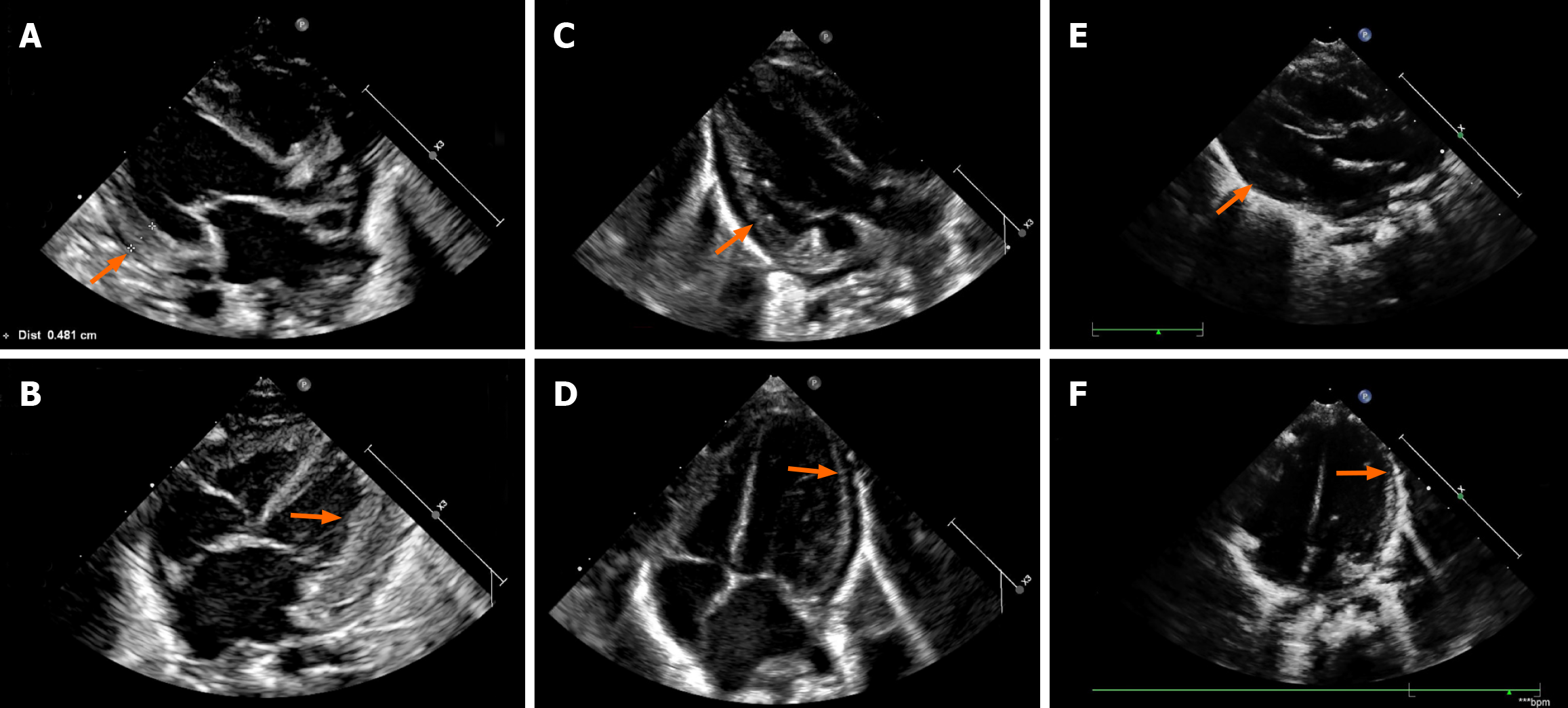

Chest radiography revealed cardiomegaly and increased pulmonary congestion (Figure 1). Echocardiography showed cardiac enlargement, marked left ventricular wall thickening (Figure 2), a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) measuring 4.5 mm in diameter, and pericardial effusion.

The infant was initially diagnosed with neonatal severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, heart failure, lactic acidosis, neonatal anemia, suspected neonatal sepsis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, extreme prematurity, and extremely low birth weight.

Treatment included invasive mechanical ventilation, aggressive sodium bicarbonate infusion for acidosis correction, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with cefoperazone-sulbactam, and hemodynamic support with dobutamine (10 μg/kg/minute) and norepinephrine (0.3-0.5 μg/kg/minute) infusions. Diuresis was induced with furosemide, and anemia was corrected with a packed red blood cell transfusion (20 mL/kg).

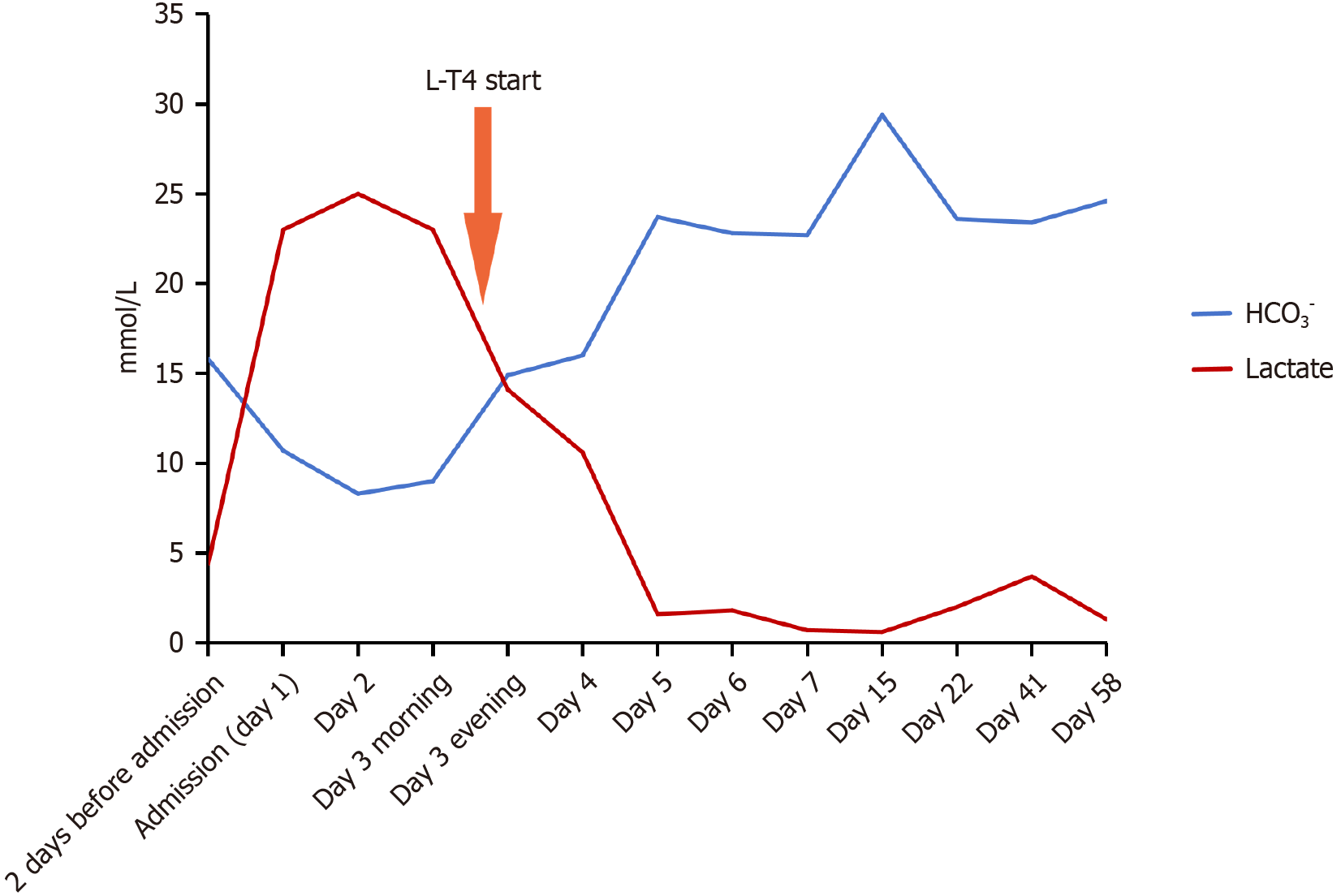

Despite comprehensive supportive measures, the lactic acidosis remained refractory to treatment. The infant developed Kussmaul respiration and exhibited cherry-red lips, indicating profound metabolic derangement. Serial blood gas analyses showed progressive clinical deterioration, with lactate levels rising to 25 mmol/L by the second hospital day (Figure 3). An extensive diagnostic evaluation was initiated to identify the etiology of the refractory lactic acidosis, including bacterial cultures, inflammatory markers, hepatic and renal function tests, and blood/urine tandem mass spectrometry, all of which remained within normal limits. Notably, the newborn screening (NBS) for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) performed on postnatal day 7 had been reported as normal. Family history was negative for metabolic or thyroid disorders, and maternal thyroid function during pregnancy was documented as normal. Given the persistent abdominal distension and refractory clinical course, thyroid function tests were repeated. The results were unequivocal: Profoundly depressed triiodothyronine [0.49 nmol/L, reference range (the same below), 1.11-3.62 nmol/L], free triiodothyronine (2.15 pmol/L, 5.1-8.0 pmol/L), thyroxine (12.80 nmol/L, 77.4-171.57 nmol/L), and free thyroxine (FT4) (1.03 pmol/L, 12.26-21.67 pmol/L) levels, accompanied by markedly elevated TSH levels > 150.000 mIU/L (1.7-9.1 mIU/L).

A diagnosis of CH was established. L-T4 replacement therapy was initiated immediately at 12.5 μg/kg/day, resulting in a rapid and dramatic clinical response.

Serum lactate levels decreased by 43.6% within 5 hours of the first L-T4 dose, with complete normalization achieved within 3 days (Figure 3). Bicarbonate levels improved correspondingly. The signs of heart failure and abdominal distension resolved markedly, with regression of hepatomegaly and resolution of peripheral edema. Follow-up echocardiography showed remarkable improvement in cardiac function and resolution of ventricular wall thickening.

The infant’s clinical course thereafter showed steady improvement. Neuroimaging at 38 weeks postmenstrual age revealed normal findings. She was successfully weaned to room air and achieved full enteral feeding. She was discharged 57 days after admission, at the postmenstrual age of 40 weeks and 4 days, with continued L-T4 therapy. Careful endocrine follow-up with dose titration maintained euthyroidism until drug discontinuation at 3 years of age (Table 2). Subsequent monitoring until 4 years of age showed normalized cardiac findings and appropriate neurodevelopment with catch-up growth. Genetic evaluation and thyroid ultrasound revealed no abnormalities.

| Age | T4 (nmol/L) | FT4 (pmol/L) | TSH (mIU/L) | TGAb (U/mL) | TPOAb (U/mL) | Dosage of L-T4 |

| 35 days | 12.80 | 1.03 | > 150.000 | NE | NE | 12.5 μg/kg/day |

| 47 days | 220.30 | 31.85 | 1.433 | < 15.0 | 165.3 | 8 μg/kg/day |

| 73 days | 134.10 | 22.65 | 0.703 | < 15.0 | 109.3 | 4.77 μg/kg/day |

| 4 months | 116.00 | 16.87 | 5.099 | NE | NE | 3.02 μg/kg/day |

| 6 months | 129.20 | 16.83 | 2.556 | NE | NE | 1.89 μg/kg/day |

| 9 months | 141.30 | 18.60 | 2.371 | NE | NE | 1.85 μg/kg/day |

| 12 months | 99.60 | 18.35 | 2.830 | NE | NE | 1.62 μg/kg/day |

| 18 months | 111.2 | 21.01 | 5.104 | NE | NE | 12.5 μg qod |

| 27 months | 113.7 | 17.61 | 4.884 | NE | NE | 12.5 μg every 2 days |

| 36 months | 105.0 | 16.83 | 4.657 | NE | NE | Stop |

| 37 months | 119.8 | 20.88 | 4.080 | NE | NE | Stop |

| Reference range | 77.4-171.57 | 12.26-21.67 | 1.7-9.1 | < 60 | < 60 |

In newborns and infants, severe lactic acidosis usually results from severe hypoxia, infection, shock, heart failure, or inborn errors of metabolism such as pyruvate carboxylase deficiency[6] or mitochondrial disorders[7]. In this case, the infant had no family history of inborn metabolism errors, and no obvious abnormalities were found in bacterial cultures, inflammatory markers, hepatic and renal function, or blood and urine tandem mass spectrometry. The refractory nature of the lactic acidosis, unresponsive to conventional therapies, highlights the primacy of thyroid hormone deficiency in this clinical presentation. The immediate and definitive resolution following L-T4 administration establishes a clear dose-effect causal relationship. Therefore, the most likely cause was heart failure and metabolic dysfunction from CH. This case exemplifies a severe, life-threatening presentation of CH, including profound cardiovascular and metabolic compromise.

Thyroid hormone receptors are extensively distributed throughout myocardial tissue and cardiac endothelial cells. Thyroid hormone reduces systemic vascular resistance while increasing heart rate, contractile force, and cardiac output[8]. Therefore, hypothyroidism can adversely affect heart muscle bioenergetics, leading to myocardial injury and dysfunction that progresses to heart failure[9], with consequent lactate overproduction. Even subclinical hypothyroidism is linked to cardiovascular risk in younger populations[10], potentially through mechanisms such as left ventricular diastolic dysfunction from endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and inflammatory state which are mediated by TSH apoptosis-derived microparticles, as well as systolic dysfunction from cardiac remodelling and increased predisposition to heart failure[11]. In this case, the infant developed heart failure and left ventricular posterior wall thickening due to hypothyroidism. L-T4 therapy rapidly normalized thyroid function and biomarkers (B-type natriuretic peptide, cardiac troponin I, lactate), and gradually reversed the structural cardiac changes. This highlights hypothyroidism as an im

A proven link exists between hypothyroidism and both heart failure and cardiac mortality. However, CH-induced se

To better understand the clinical manifestations of the cardiac effects of hypothyroidism in children, we reviewed 21 previously reported cases of cardiac dysfunction directly or partly caused by hypothyroidism in children (Supple

Owing to the transplacental passage of maternal thyroid hormones, which provide protective effects for approximately 2 weeks after birth, only 1%-4% of infants with CH are detected by clinical examination at birth[8]. As neonatal manifestations are often subtle or atypical, most countries have established NBS programs to identify infants at high risk. However, a crucial aspect of this case, as evidenced by screening data over recent decades, involves the limitations of initial NBS in preterm infants, having increased risk for delayed TSH elevation, up to a maximum age of 56 days of life[2,3]. European guidelines (2021) recommend repeat screening at 10-14 days after birth for preterm infants[1], while current guidelines (2023) advise a second NBS at 2-4 weeks of age, even after a normal initial result, for neonates meeting any of the following criteria: Acute illness requiring admission; prematurity (< 32 weeks gestation); very low birth weight (< 1500 g); transfusion prior to the first NBS; monozygotic (or same-sex twin if zygosity is unknown) or multiple birth status; or trisomy 21. Given its considerably lower cost, repeat NBS is preferred over serum TSH and FT4 testing in these cases[34]. In addition, some centers perform a third screen at 6-8 weeks of age for extremely preterm infants to enhance detection, though this increases false-positive risks and costs[2]. A study of 5992 very preterm Chinese infants reported that dynamic thyroid function screening by weeks throughout the first month of life is crucial for the timely diagnosis and treatment of CH[35].

Additionally, research suggests that a lower TSH cut-off may be appropriate for second screenings, as preterm infants < 34 weeks more commonly exhibit blood TSH levels of 5-9.9 mIU/L than ≥ 10 mIU/L[36]. Some protocols employ a two-stage screen (TSH cut-off 8 mIU/L at 48-72 hours, then 6 mIU/L at 2 weeks)[2]. However, an Australian study reported that while a lower threshold (≥ 8 mIU/L) improved CH detection, it also increased recall rates eightfold[37]. In the present case, the primary focus on managing prematurity-related complications likely led to the omission of a repeat thyroid function test. This omission highlights the critical need for rigorous adherence to follow-up screening protocols[34], a trade-off that merits further clinical and economic evaluation.

The management of critically ill infants with CH necessitates aggressive hormone replacement. Current guidelines recommend that neonates diagnosed with CH through a second screening begin L-T4 treatment as soon as possible, and no later than 2 weeks after birth or immediately after confirmatory thyroid function testing, with the initial dose individualized based on TSH and FT4 levels[1]. The 2025 Chinese guidelines advise a full initial replacement L-T4 dose to rapidly normalize thyroid hormone levels within 2 weeks and TSH within 4 weeks. Specifically, the recommended initial dose for mild CH cases (FT4 > 10 pmol/L with elevated TSH) is 10 μg/kg/day, while 10-15 μg/kg/day for severe CH cases (FT4 < 5 pmol/L with elevated TSH)[38]. In this case, an initial L-T4 dose of 12.5 μg/kg/day was critical for rapidly reversing severe deficiency and cardiac dysfunction; however, it later led to elevated FT4 levels, necessitating careful follow-up and downward titration to prevent iatrogenic hyperthyroidism, a particular concern at L-T4 doses exceeding 10.2 μg/kg/day[39]. While overtreatment should be avoided, excessive caution should not lead to undertreatment, which may increase the risk of suboptimal neurodevelopmental outcomes. A balanced approach to dosing and vigilant monitoring is essential in optimizing outcomes for these infants.

However, causal inference in individual cases has inherent limitations. Furthermore, this atypical CH case, with normal initial TSH and ultrasound, presented diagnostic ambiguity. The long-term impact of our treatment on her neurological outcomes requires continued follow-up, with imaging and neurological assessments.

This case serves as an essential reminder to clinicians that CH can represent a reversible etiology of cardiovascular collapse in infants. In any infant, particularly those born preterm, presenting with unexplained heart failure, shock, or refractory lactic acidosis, thyroid function must be urgently evaluated regardless of previous NBS results. Prompt diagnosis and initiation of thyroxine replacement therapy can be life-saving and facilitate excellent cardiac and neur

We would like to thank You Lu for collecting data.

| 1. | van Trotsenburg P, Stoupa A, Léger J, Rohrer T, Peters C, Fugazzola L, Cassio A, Heinrichs C, Beauloye V, Pohlenz J, Rodien P, Coutant R, Szinnai G, Murray P, Bartés B, Luton D, Salerno M, de Sanctis L, Vigone M, Krude H, Persani L, Polak M. Congenital Hypothyroidism: A 2020-2021 Consensus Guidelines Update-An ENDO-European Reference Network Initiative Endorsed by the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and the European Society for Endocrinology. Thyroid. 2021;31:387-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tuli G, Munarin J, Topalli K, Pavanello E, de Sanctis L. Neonatal Screening for Congenital Hypothyroidism in Preterm Infants: Is a Targeted Strategy Required? Thyroid. 2023;33:440-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brown A, Hofman P, Webster D, Heather N. Screening Blind Spot: Missing Preterm Infants in the Detection of Congenital Hypothyroidism. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2025;11:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chaker L, Papaleontiou M. Hypothyroidism: A Review. JAMA. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Subspecialty Group of Neonatology; the Society of Pediatric; Chinese Medical Association; Professional Committee of Infectious Diseases, Neonatology Society, Chinese Medical Doctor Association. [Expert consensus on the diagnosis and management of neonatal sepsis (version 2019)]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2019;57:252-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xue M. Case Report: Prenatal neurological injury in a neonate with pyruvate carboxylase deficiency type B. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1199590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shimozawa H, Sato T, Osaka H, Takeda A, Miyauchi A, Omika N, Yada Y, Kono Y, Murayama K, Okazaki Y, Kishita Y, Yamagata T. A Case of Infantile Mitochondrial Cardiomyopathy Treated with a Combination of Low-Dose Propranolol and Cibenzoline for Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Stenosis. Int Heart J. 2022;63:970-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cavarzere P, Mancioppi V, Battiston R, Lupieri V, Morandi A, Maffeis C. Primary congenital hypothyroidism: a clinical review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1592655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kahaly GJ, Liu Y, Persani L. Hypothyroidism: playing the cardiometabolic risk concerto. Thyroid Res. 2025;18:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang P, Zhang W, Liu H. Research status of subclinical hypothyroidism promoting the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025;12:1527271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bielecka-Dabrowa A, Godoy B, Suzuki T, Banach M, von Haehling S. Subclinical hypothyroidism and the development of heart failure: an overview of risk and effects on cardiac function. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | El-Khuffash A, Levy PT, Gorenflo M, Frantz ID 3rd. The definition of a hemodynamically significant ductus arteriosus. Pediatr Res. 2019;85:740-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Williams LH, Jayatunga R, Scott O. Massive pericardial effusion in a hypothyroid child. Br Heart J. 1984;51:231-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanda S, Newfield RS. A child with pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade due to previously unrecognized hypothyroidism. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1411-1413. [PubMed] |

| 15. | De Sanctis V, Govoni MR, Sprocati M, Marsella M, Conti E. Cardiomyopathy and pericardial effusion in a 7 year-old boy with beta-thalassaemia major, severe primary hypothyroidism and hypoparathyroidism due to iron overload. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6 Suppl 1:181-184. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Anah MU, Ansa VO, Etiuma AU, Udoh EE, Ineji EO, Asindi AA. Recurrent pericardial effusion associated with hypothyroidism in Down Syndrome: a case report. West Afr J Med. 2011;30:210-213. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Leonardi A, Penta L, Cofini M, Lanciotti L, Principi N, Esposito S. Pericardial Effusion as a Presenting Symptom of Hashimoto Thyroiditis: A Case Report. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mangaraj S. Hypothyroidism Presenting as Cardiac Emergency. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54:1404-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mansueto ML, Zagni G, Sartori C, Olivares Bermudez BA, Righi B, Catellani C, Fusco C, Frasoldati A, De Fanti A, Iughetti L, Street ME. Late diagnosis of severe long-standing autoimmune hypothyroidism after the first lockdown for the Covid-19 pandemic: clinical features and follow-up. Acta Biomed. 2022;92:e2021239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thompson MD, Henry RK. Myxedema Coma Secondary to Central Hypothyroidism: A Rare but Real Cause of Altered Mental Status in Pediatrics. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;87:350-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nakanomori A, Nagano N, Seimiya A, Okahashi A, Morioka I. Fetal Sinus Bradycardia Is Associated with Congenital Hypothyroidism: An Infant with Ectopic Thyroid Tissue. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;248:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Janson A, Hällström C, Iversen M, Finder M, Elimam A, Nergårdh R. Initial low-dose oral levothyroxine in a child with Down syndrome, myxedema, and cardiogenic shock. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1291-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Olguntürk R, Tunaoğlu FS, Oğuz D, Cinaz P, Bideci A. Complete atrioventricular heart block in congenital hypothyroidism. Turk J Pediatr. 1998;40:431-435. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Zhang N, Shao S, Yan Y, Hua Y, Zhou K, Wang C. Case Report: Hypothyroidism Misdiagnosed as Fulminant Myocarditis in a Child. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:698089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fusco FP, Sindico P, Pia De Carolis M, Costa S, Cota F, De Rosa G, Romagnoli C. Hypertrabecular aspect of left ventricular myocardium: a possible complication of congenital hypothyroidism in a preterm infant. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:732-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chimatapu SN, Schachter JL, Batra AS, Sirignano R, Okawa ER. A Pediatric Case of Refractory Torsades de Pointes in Autoimmune Hypothyroidism. JCEM Case Rep. 2024;2:luae124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Drop SL, Krenning EP, Docter R, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM, Visser TJ, Hennemann G. Congenital hypothyroidism and partial thyroid hormone unresponsiveness of the pituitary in a patient with congenital thyroxine binding albumin elevation. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149:90-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zaki SA, Dolas A. Refractory cardiogenic shock in an infant with congenital hypothyroidism. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pokrajac D, Zergollern L, Gjergja Z. [Cardiac insufficiency--a rare major symptom of hypothyroidism in an infant]. Lijec Vjesn. 1989;111:144-147. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Jain V, Kannan L, Kumar P. Congenital hypopituitarism presenting as dilated cardiomyopathy in a child. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2011;24:767-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Choi Y, Jung SY, Park JM, Suh J, Shin EJ, Chae HW, Kim HS, Kwon A. Combination therapy of liothyronine and levothyroxine for hypothyroidism-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2023;28:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Altman DI, Murray J, Milner S, Dansky R, Levin SE. Asymmetric septal hypertrophy and hypothyroidism in children. Br Heart J. 1985;54:533-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kerbage J, Dairo OO, Ketchum L, Smith C, Tobias JD. Pulseless Electrical Activity and Perioperative Cardiac Arrest Due to Undiagnosed and Asymptomatic Hypothyroidism During Outpatient Surgery in an Adolescent. Cardiol Res. 2023;14:468-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rose SR, Wassner AJ, Wintergerst KA, Yayah-Jones NH, Hopkin RJ, Chuang J, Smith JR, Abell K, LaFranchi SH; Section on Endocrinology Executive Committee; Council on Genetics Executive Committee. Congenital Hypothyroidism: Screening and Management. Pediatrics. 2023;151:e2022060419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shi R, Jiang J, Wang B, Liu F, Liu X, Yang D, Li Z, He H, Sun X, Liu Q, Li H, He J, Yu J, Zhang M, Reddy S, Yu Y, Zhao J. Dynamic Screening of Thyroid Function for the Timely Diagnosis of Congenital Hypothyroidism in Very Preterm Infants: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2023;33:1055-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Vincenzi G, Petralia IT, Abbate M, Vigone MC. 50 years of newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism: evolution of insights in etiology, diagnosis and management: Transient or permanent congenital hypothyroidism: from milestones to current and future perspectives. Eur Thyroid J. 2025;14:e250019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yu A, Alder N, Lain SJ, Wiley V, Nassar N, Jack M. Outcomes of lowered newborn screening thresholds for congenital hypothyroidism. J Paediatr Child Health. 2023;59:955-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Working Group on Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Congenital Hypothyroidism; Chinese Society of Endocrinology; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Pediatric Society; Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of congenital hypothyroidism]. Zhonghua Neifenmi Daixie Zazhi. 2025;41:267-289. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Chooprasertsuk N, Dejkhamron P, Unachak K, Wejaphikul K. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism in primary congenital hypothyroidism: prevalence and predictive factors. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022;35:1250-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/