Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.114672

Revised: October 25, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 80 Days and 7.4 Hours

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressants to control inflammation. Drugs like azathioprine (AZA) and anti-tumor necrosis factor agents increase the risk of extraintestinal malignancies. However, no association has been established between these therapies and endo

Female, 49 years old, with UC pancolitis extension since 2017. She used aminosalicylates and AZA with non-response. She started infliximab and AZA combination therapy in 2020, with optimization in 2021 due to endoscopic activity. In the same year, the patient presented to the emergency room with ascitis and underwent diagnostic paracentesis, which showed serum-ascites albumin gradient < 1.1 g/dL, absence of neoplastic cells, and abdominal and pelvic tomography reported a hypoechoic nodular lesion in the posterior wall of the uterus and elevated carbohydrate antigen 125. Given the suspicion of neoplasia, the suspension of immunosuppressive therapy was indicated. The patient underwent a total abdo

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have a higher risk of cancer due to inflammation or treatment. Proper screening with multidisciplinary care can improve outcomes.

Core Tip: Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunosuppressants. Though rare, treatments such as azathioprine and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy may increase the risk of extraintestinal cancers. This report describes a patient with ulcerative colitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy who was diagnosed with endometrial stromal sarcoma during treatment. Clinical, diagnostic, imaging, and treatment details are discussed. The case highlights the importance of understanding medication side effects to enhance patient safety, prognosis, and quality of life.

- Citation: Soares AABDS, Grillo TG, Almeida LC, Cavalleiro GST, Lopes MA, Craveiro MMS, Herrerias GSP, Baima JP, Saad-Hossne R, Sassaki LY. Endometrial stromal sarcoma in a patient with ulcerative colitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(35): 114672

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i35/114672.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.114672

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease resulting from genetic and environmental factors[1]. It is characterized by relapsing inflammation of the colonic mucosa, typically starting in the rectum[2,3]. Treatment is guided by disease severity and includes conventional therapies (e.g., aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators) and advanced options such as biologics [anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents, anti-integrins, anti-interleukins] and small molecules like Janus Kinase inhibitors and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators[4,5]. Thiopurines [e.g., azathioprine (AZA)] are effective for maintenance in patients unresponsive to mesalamine or those requiring repeated corticosteroid courses[6,7]. Anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab) are recommended for induction and maintenance in patients with moderate-to-severe UC who are unresponsive to conventional therapy[5]. Treatment selection depends on clinical factors, cost, adherence, and drug availability[8]; however, therapeutic complexity has increased, along with concerns about adverse effects[9,10].

Long-term immunosuppression may increase the risk of malignancies related to chronic inflammation or drug exposure. While intestinal cancers are linked to inflammation, extraintestinal neoplasms (melanoma, non-melanoma skin cancers, lymphomas, cervical and urinary tract cancers) are more commonly associated with immunosuppression[11-13]. Endometrial stromal sarcoma is a rare uterine malignancy affecting women aged 40-50 years, representing < 1% of gynecological cancers[14-16]. Although factors like tamoxifen, unopposed estrogens exposure, and polycystic ovary syndrome may contribute to its development[17,18], no current evidence links AZA, anti-TNF agents, or UC itself to its development. This report presents an unusual case of a patient with UC who developed endometrial stromal sarcoma while receiving infliximab and AZA, along with a review of the literature.

A woman with UC receiving treatment with infliximab and AZA presented to the emergency room with progressive abdominal discomfort and distension.

A 49-year-old female patient was diagnosed with UC with pancolitis in April 2017, presenting with abdominal pain, oral aphthae, and diarrhea containing mucus and blood. Colonoscopy revealed ulcerated lesions in the ascending colon and mucosal changes in the sigmoid and rectum, including edema, erythema, friability, and pinpoint erosions covered by fibrin (Endoscopic Mayo score: 3). Histological analysis showed chronic inflammation with focal inflammatory activity and crypt abscess formation. Initial treatment included oral mesalamine (4 g/day) and mesalamine suppositories (1 g/day), followed by AZA (150 mg/day), with no clinical response. Combination therapy with infliximab (5 mg/kg) and AZA (150 mg/day) was initiated in November 2020, with optimization to 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks in July 2021 owing to persistent endoscopic activity (Endoscopic Mayo score: 2). In the same month, the patient presented to the emergency department with progressive abdominal discomfort and distension lasting two weeks.

There was no past illness history of gynecological malignancies.

There was no family history of gynecological malignancies.

Physical examination revealed ascites.

Diagnostic paracentesis showed a serum-ascites albumin gradient of < 1.1 and absence of malignant cells. Tumor marker analysis revealed an elevated carbohydrate antigen 125 level of 248.4 U/mL (reference: ≤ 30.2 U/mL), prompting referral for gynecological evaluation.

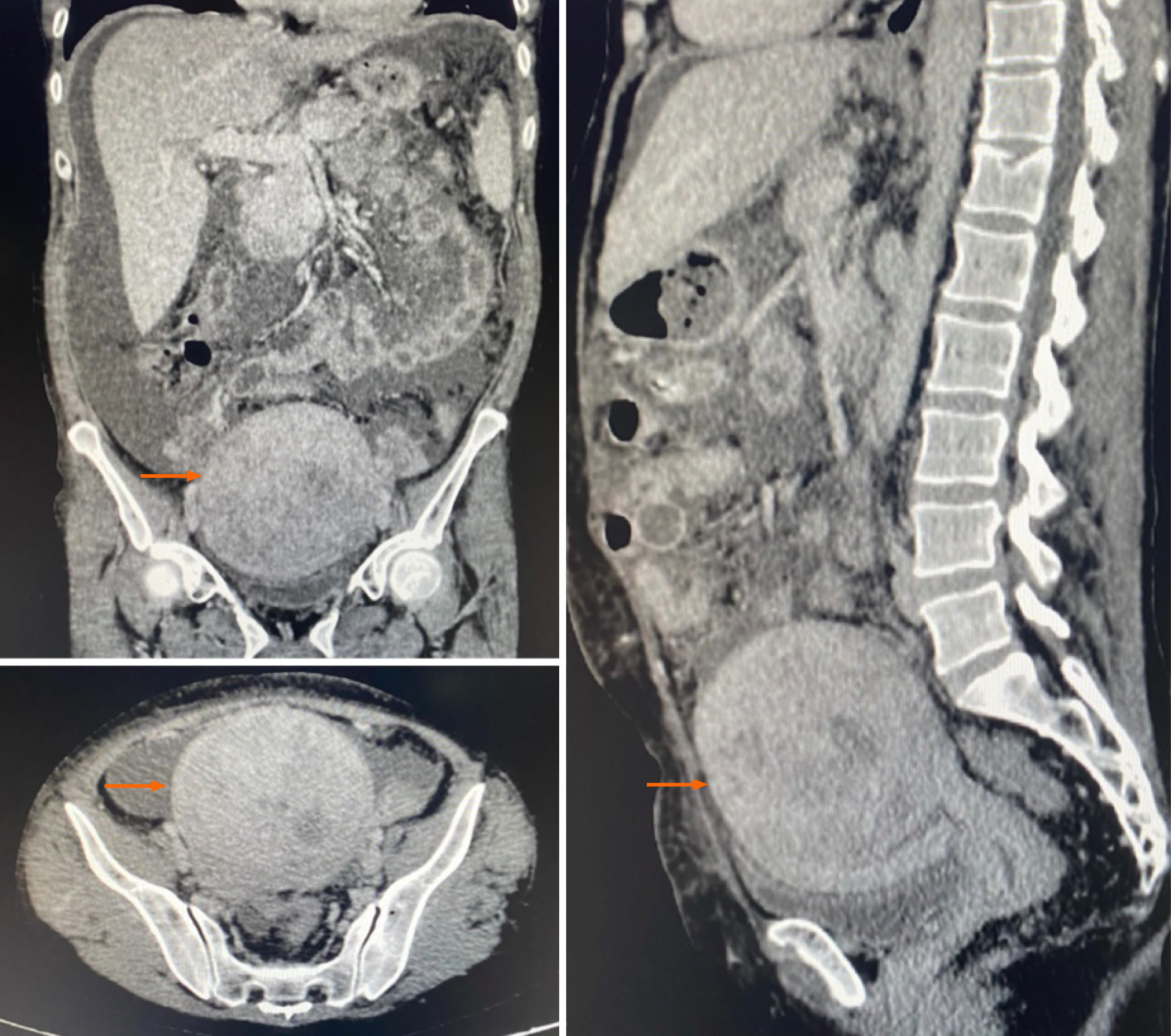

Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis identified a hypoechoic nodular lesion located in the posterior wall/fundus of the uterus, measuring 9.8 cm × 6.8 cm × 10.3 cm (estimated volume: 351.3 cm3) on ultrasound and 10.4 cm × 10.1 cm × 9.4 cm (estimated volume: 523.3 cm3) on computed tomography (Figure 1), indicative of a leiomyoma or one of its histopathological variants.

The final diagnosis was endometrial sarcoma in a patient with UC.

Given that clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings supported the hypothesis of ascites secondary to a gynecologic malignancy, immunosuppressive therapy was discontinued in August 2021. The patient subsequently underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in October 2021. Histopathological analysis confirmed a low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma confined to the body of the uterus, for which neither adjuvant chemotherapy nor radiotherapy was considered necessary.

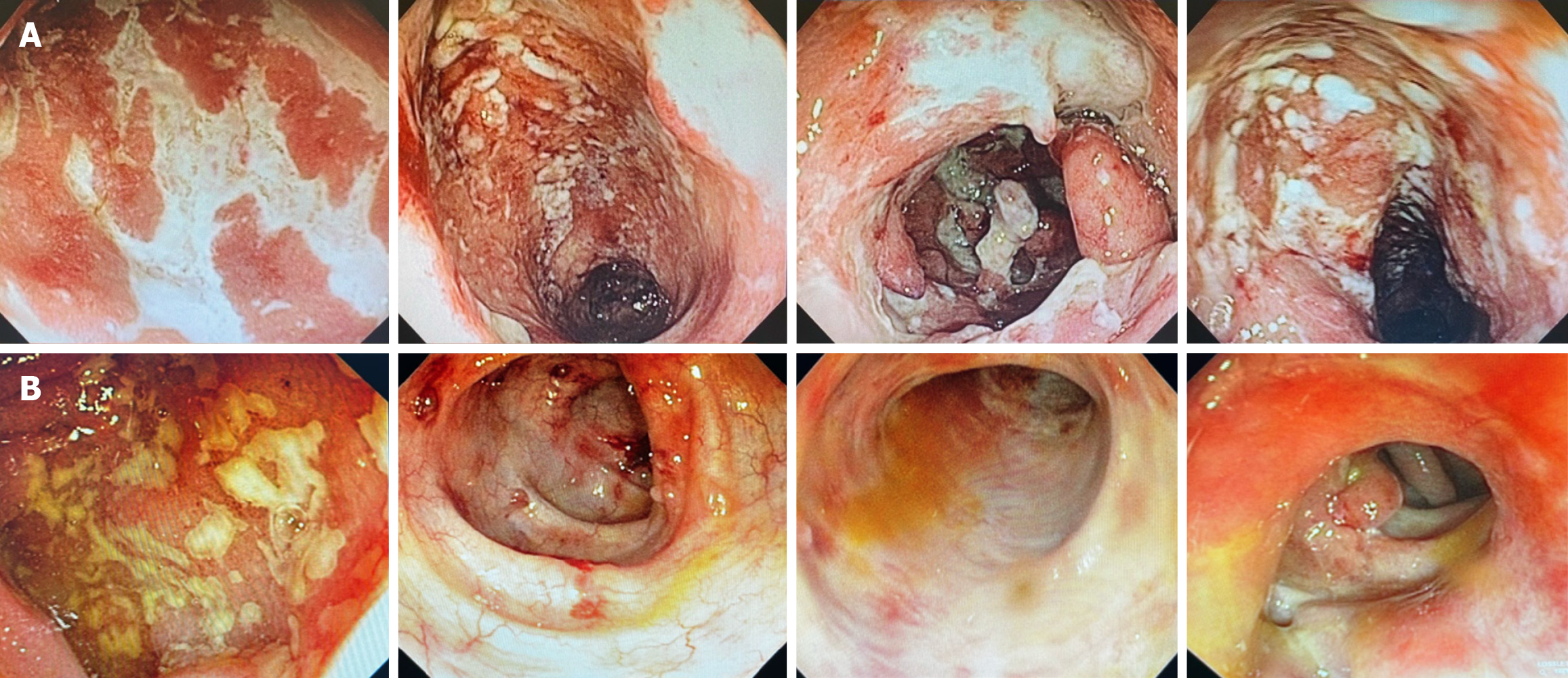

At a follow-up visit with the gastroenterology clinic after surgery, the patient reported continued use of AZA (150 mg/day). Although she experienced well-formed stools and postoperative improvement in abdominal pain, she complained of pain in the perianal region following defecation. In this context, AZA was definitively discontinued, and initiation of vedolizumab was planned. While awaiting approval for the anti-integrin agent, oral mesalamine (3.2 g/day) was prescribed for symptomatic management. In January 2022, the patient experienced worsening in intestinal symptoms, including bloody diarrhea and persistent perianal pain. She self-initiated prednisone (35 mg/day). A planned tapering of corticosteroids was implemented, along with an increased mesalamine dose to 4.8 g/day. The patient received the first dose of the anti-integrin agent in April 2022, with gradual discontinuation of mesalamine. During the induction phase (weeks 0, 2, and 6), she continued to exhibit clinical disease activity, with passage of mucus and blood via the anal canal. A follow-up colonoscopy was performed in 2022 to assess the response to vedolizumab after two months of therapy. The examination (Figure 2A) revealed areas of edema with complete loss of submucosal vascular pattern, marked erythema and multiple confluents, linear fibrin-covered erosions, approximately 25 cm from the anal verge; as well as severe edema and erythema of the rectum, with friability and two deep ulcers of about 15 mm each (Endoscopic Mayo score: 3). Owing to persistent clinical and endoscopic activity, the patient was considered a primary non-responder to vedolizumab. Total proctocolectomy was recommended in light of clinical refractoriness and a history of malignancy, but the patient refused surgical intervention. She is currently clinically stable and asymptomatic, maintained on oral mesalamine (3 g/day) and rectal suppositories (500 mg/day). Nevertheless, her most recent colonoscopy in 2024 revealed severe inflammatory activity, with an Endoscopic Mayo score of 3 (Figure 2B).

The association between IBD and malignancies is well established in the literature. These tumors arise either from chronic tissue inflammation and/or from immunosuppression induced by medications such as AZA and anti-TNF agents[12,13].Those associated with chronic inflammation result in intestinal malignancies such as colorectal cancer, small bowel adenocarcinoma, intestinal lymphoma, and anal cancer[12,13]. In contrast, immunosuppression-related neoplasms are predominantly extraintestinal, including skin cancer (melanoma and non-melanoma), hematologic cancers (lymphoma), as well as cervical and urinary tract cancers[12,13]. In recent years, both the incidence and prevalence of IBD-associated cancers have declined, reflecting advances in therapeutic options and the implementation of more effective surveillance strategies[19-21].

Multiple risk factors for neoplasm development have been identified, including medications used for the treatment of IBD. Among the most well-established risk factors are disease extent and duration[19]; the greater the colonic involve

From a pharmacological perspective, thiopurines have been associated with an increased risk of lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative disorders, particularly in older adults[22]. They play a role in the development of B-cell lymphomas, particularly Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas, in patients with IBD[23-26] receiving thiopurines either as monotherapy or in combination with anti-TNF agents[27]. Such patients have a 3-fold to 5-fold increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative diseases[23,25]. Although the evidence remains inconclusive regarding the isolated risk of lymphomas associated with anti-TNF therapy[12,28-32], studies clearly show a higher risk with combination therapy (anti-TNF agents plus thiopurine) than with monotherapy using either agent[22].

The most common cancer in humans is NMSC[33]; both current and past exposure to thiopurines significantly increase the risk of NMSC in patients with IBD[22,33-35]. Conversely, exposure to anti-TNF agents has been associated with an increased risk of melanoma[36,37]. However, no evidence indicates that the risk of skin cancer is higher with combination therapy (anti-TNF plus thiopurine) than with monotherapy[22]. Regarding urinary tract malignancies, thiopurine use in patients with IBD has been linked to a higher risk of kidney and bladder cancer, particularly among older male patients and smokers[38,39]. This increased risk has not been observed with the use of anti-TNF agents[36].

With respect to cervical cancer, patients receiving thiopurines appear to have a higher risk of high-grade cervical dysplasia and cancer than the general population without IBD, as demonstrated in a meta-analysis by Allegretti et al[40]. However, whether immunosuppressive therapy is independently associated with a higher risk of cervical dysplasia in patients with IBD remains nuclear[11,41]. In the present case report, the patient developed endometrial stromal sarcoma while on thiopurine (AZA) in combination with anti-TNF therapy (infliximab). This aligns with existing evidence indicating an increased risk of lymphoma with this drug combination; however, no evidence supports an increased risk of solid organ or skin cancers in such cases[22,28]. Furthermore, no data exists in the literature linking the development of endometrial stromal sarcoma to the use of either thiopurines or anti-TNFs[22,28].

For non-cutaneous solid tumors, the continuation of anti-TNF agents is generally recommended, except in cases where cytotoxic chemotherapy is administered concurrently, or metastatic disease is present[13]. In this case, infliximab was discontinued owing to initial uncertainty regarding the primary site of the neoplasm and the potential need for adjuvant chemotherapy. In patients diagnosed with lymphoma, clinicians should discontinue anti-TNF therapy during treatment and consider transitioning to a biologic with an alternative mechanism of action[13]. Conversely, for patients with NMSC, continuation of all biologic therapies is generally advised. However, in cases of melanoma, anti-TNF agents should be discontinued during oncologic treatment and replaced with a drug with an alternative mechanism of action once cancer therapy is completed. For patients with a history of malignancy in remission, biologic therapy need not be suspended, except in instances of metastatic melanoma, given its well-recognized potential for late recurrence[13].

Regarding thiopurines, although these agents exhibit carcinogenic potential, this effect seems to be reversible upon drug discontinuation[12]. Patients with IBD and a prior history of cancer do not appear to have additional malignancy risk with thiopurine use beyond the known baseline risk of this drug class. However, thiopurines should be withdrawn in cases of active malignancy[22], as was done with the present patient, where AZA was discontinued following the cancer diagnosis. Nevertheless, in the presence of pre-neoplastic cervical lesions or non-aggressive basal cell carcinoma, continuation of thiopurines may be considered under close surveillance[22]. Some studies have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy with the use of vedolizumab, an anti-integrin biologic agent[42]. Moreover, patients receiving vedolizumab may continue treatment even in the setting of cutaneous or non-cutaneous malignancies (solid tumors or lymphoma), regardless of the need for chemotherapy[13]. Accordingly, in the present case, the patient started vedolizumab after the cancer treatment.

Although patients with IBD face an elevated risk of developing extraintestinal solid tumors, current evidence does not support distinct strategies for their prevention or early detection. Establishing a direct causal link between cancer development and a specific medication is also challenging, as most patients are exposed to multiple therapies over time, making it difficult to attribute adverse outcomes to a single agent. In this context, individuals with IBD should be encouraged to follow the same primary and secondary prevention programs as the general population for extraintestinal solid tumors, with consideration of their individual risk profiles[22]. This report has some limitations. Being an isolated case, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship between the use of immunosuppressants (AZA) and biological agents (infliximab) with the development of endometrial stromal sarcoma through the data from this report alone. The rarity of this neoplasm and the lack of epidemiological data supporting an association with UC or the medications used prevent generalizations. Furthermore, other potential risk factors, such as prior hormonal exposures or genetic factors, could not be fully evaluated. Finally, the clinical follow-up period remains limited, which prevents conclusions about long-term outcomes, such as tumor recurrence or sustained response to the new biological agent.

Physicians must be attentive to the adverse effects of pharmacological therapies and should periodically reassess combination therapies, safety profiles, and the indications and contraindications of each agent. Regular oncological monitoring is necessary for patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Multidisciplinary evaluation is essential in cases of malignancy, and immediate discontinuation of immunosuppressants is warranted in the event of active cancer. Finally, preventive and screening measures should be implemented according to population-based guidelines.

| 1. | Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagórowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1580] [Cited by in RCA: 1367] [Article Influence: 151.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, Kucharzik T, Adamina M, Annese V, Bachmann O, Bettenworth D, Chaparro M, Czuber-Dochan W, Eder P, Ellul P, Fidalgo C, Fiorino G, Gionchetti P, Gisbert JP, Gordon H, Hedin C, Holubar S, Iacucci M, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Lakatos PL, Lytras T, Lyutakov I, Noor N, Pellino G, Piovani D, Savarino E, Selvaggi F, Verstockt B, Spinelli A, Panis Y, Doherty G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 584] [Cited by in RCA: 661] [Article Influence: 165.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV Jr, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2148] [Cited by in RCA: 2422] [Article Influence: 201.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kucharzik T, Molnár T, Raine T, Sebastian S, de Sousa HT, Dignass A, Carbonnel F; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 910] [Article Influence: 101.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Baima JP, Imbrizi M, Andrade AR, Chebli LA, Argollo MC, Queiroz NSF, Azevedo MFC, Vieira A, Costa MHM, Fróes RSB, Penna FGCE, Quaresma AB, Damião AOMC, Moraes ACDS, Santos CHMD, Flores C, Zaltman C, Vilela EG, Morsoletto E, Gonçalves Filho FA, Santana GO, Zabot GP, Parente JML, Sassaki LY, Zerôncio MA, Machado MB, Cassol OS, Kotze PG, Parra RS, Miszputen SJ, Coy CSR, Ambrogini Junior O, Chebli JMF, Saad-Hossne R. Second Brazilian Consensus On The Management Of Ulcerative Colitis In Adults: A Consensus Of The Brazilian Organization For Crohn's Disease And Colitis (Gediib). Arq Gastroenterol. 2023;59:51-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Timmer A, McDonald JW, Macdonald JK. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;CD000478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stournaras E, Qian W, Pappas A, Hong YY, Shawky R; UK IBD BioResource Investigators, Raine T, Parkes M; UK IBD Bioresource Investigators. Thiopurine monotherapy is effective in ulcerative colitis but significantly less so in Crohn's disease: long-term outcomes for 11 928 patients in the UK inflammatory bowel disease bioresource. Gut. 2021;70:677-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, Hayee B, Lomer MCE, Parkes GC, Selinger C, Barrett KJ, Davies RJ, Bennett C, Gittens S, Dunlop MG, Faiz O, Fraser A, Garrick V, Johnston PD, Parkes M, Sanderson J, Terry H; IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group, Gaya DR, Iqbal TH, Taylor SA, Smith M, Brookes M, Hansen R, Hawthorne AB. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1-s106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1929] [Cited by in RCA: 1713] [Article Influence: 244.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Laredo V, Gargallo-Puyuelo CJ, Gomollón F. How to Choose the Biologic Therapy in a Bio-naïve Patient with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Med. 2022;11:829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Queiroz NSF, Regueiro M. Safety considerations with biologics and new inflammatory bowel disease therapies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020;36:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Magro F, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sokol H, Aldeger X, Costa A, Higgins PD, Joyce JC, Katsanos KH, Lopez A, de Xaxars TM, Toader E, Beaugerie L. Extra-intestinal malignancies in inflammatory bowel disease: results of the 3rd ECCO Pathogenesis Scientific Workshop (III). J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:31-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Greuter T, Vavricka S, König AO, Beaugerie L, Scharl M; Swiss IBDnet, an official working group of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Malignancies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion. 2020;101 Suppl 1:136-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Click B, Regueiro M. A Practical Guide to the Safety and Monitoring of New IBD Therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:831-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Puliyath G, Nair VR, Singh S. Endometrial stromal sarcoma. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2010;31:21-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Molina-Loza E, Altez-Navarro C. Sarcoma del estroma endometrial de grado alto: presentación de un caso. Rev Peru Ginecol Obstet. 2011;57:2304-5132. |

| 16. | Soriano Sarrió P, Martínez-Rodríguez M, Soriano D, Llombart-Bosch A, Navarro S. Sarcoma de estroma endometrial. Estudio clinicopatológico e inmunofenotípico de 5 casos. Rev Esp Patol. 2007;40:40-45. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Puliyath G, Nair MK. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: A review of the literature. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2012;33:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cohen I. Endometrial pathologies associated with postmenopausal tamoxifen treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:256-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beaugerie L, Itzkowitz SH. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1441-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jess T, Horváth-Puhó E, Fallingborg J, Rasmussen HH, Jacobsen BA. Cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease according to patient phenotype and treatment: a Danish population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1869-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:375-81.e1; quiz e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gordon H, Biancone L, Fiorino G, Katsanos KH, Kopylov U, Al Sulais E, Axelrad JE, Balendran K, Burisch J, de Ridder L, Derikx L, Ellul P, Greuter T, Iacucci M, Di Jiang C, Kapizioni C, Karmiris K, Kirchgesner J, Laharie D, Lobatón T, Molnár T, Noor NM, Rao R, Saibeni S, Scharl M, Vavricka SR, Raine T. ECCO Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:827-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, Larson RJ, Sands BE. Risk of lymphoma associated with combination anti-tumor necrosis factor and immunomodulator therapy for the treatment of Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:874-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, Colombel JF, Lémann M, Cosnes J, Hébuterne X, Cortot A, Bouhnik Y, Gendre JP, Simon T, Maynadié M, Hermine O, Faivre J, Carrat F; CESAME Study Group. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617-1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 823] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Khan N, Abbas AM, Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV Jr, Bazzano LA. Risk of lymphoma in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1007-1015.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chupin A, Perduca V, Meyer A, Bellanger C, Carbonnel F, Dong C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: comparative risk of lymphoma with anti-tumour necrosis factor agents and/or thiopurines in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1289-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, Carrat F, Zureik M, Carbonnel F, Dray-Spira R. Association Between Use of Thiopurines or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Alone or in Combination and Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JAMA. 2017;318:1679-1686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Afif W, Sandborn WJ, Faubion WA, Rahman M, Harmsen SW, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV Jr. Risk factors for lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1384-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kopylov U, Vutcovici M, Kezouh A, Seidman E, Bitton A, Afif W. Risk of Lymphoma, Colorectal and Skin Cancer in Patients with IBD Treated with Immunomodulators and Biologics: A Quebec Claims Database Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1847-1853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | DʼHaens G, Reinisch W, Panaccione R, Satsangi J, Petersson J, Bereswill M, Arikan D, Perotti E, Robinson AM, Kalabic J, Alperovich G, Thakkar R, Loftus EV. Lymphoma Risk and Overall Safety Profile of Adalimumab in Patients With Crohn's Disease With up to 6 Years of Follow-Up in the Pyramid Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:872-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yang C, Huang J, Huang X, Huang S, Cheng J, Liao W, Chen X, Wang X, Dai S. Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated With Anti-tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha Agents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1042-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Diepgen TL, Mahler V. The epidemiology of skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146 Suppl 61:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 785] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, Bouvier AM, Chevaux JB, Simon T, Carbonnel F, Colombel JF, Dupas JL, Godeberge P, Hugot JP, Lémann M, Nahon S, Sabaté JM, Tucat G, Beaugerie L; Cesame Study Group. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1621-28.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Ariyaratnam J, Subramanian V. Association between thiopurine use and nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nyboe Andersen N, Pasternak B, Basit S, Andersson M, Svanström H, Caspersen S, Munkholm P, Hviid A, Jess T. Association between tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists and risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2014;311:2406-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Long MD, Martin CF, Pipkin CA, Herfarth HH, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:390-399.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Pasternak B, Svanström H, Schmiegelow K, Jess T, Hviid A. Use of azathioprine and the risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1296-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bourrier A, Carrat F, Colombel JF, Bouvier AM, Abitbol V, Marteau P, Cosnes J, Simon T, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Beaugerie L; CESAME study group. Excess risk of urinary tract cancers in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:252-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Allegretti JR, Barnes EL, Cameron A. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease on chronic immunosuppressive therapy at increased risk of cervical high-grade dysplasia/cancer? A meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1089-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hazenberg HMJL, de Boer NKH, Mulder CJJ, Mom SH, van Bodegraven AA, Tack Md PhD GJ. Neoplasia and Precursor Lesions of the Female Genital Tract in IBD: Epidemiology, Role of Immunosuppressants, and Clinical Implications. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:510-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Luthra P, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1227-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/