Published online Dec 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.114352

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: December 6, 2025

Processing time: 79 Days and 19.6 Hours

The special physiological changes during pregnancy pose a huge challenge to the diagnosis of cervical cancer in pregnancy (CCIP). However, due to the poor prognosis of advanced-stage CCIP, there is currently no consensus or guideline for diagnosis and treatment.

In this case report, we presented the case of a 30-year-old woman at 30 weeks of gestation who presented with irregular vaginal bleeding and was admitted to a local hospital at 35 weeks of gestation with a sudden gush of fluid and underwent a C-section. During the surgery, a rotten fish-like solid mass in the lower segment of the posterior wall of the uterus was excised for biopsy. The patient was referred to our hospital because she experienced heavy vaginal bleeding 13 days after one chemotherapy session. The solid mass was initially misdiagnosed as uterine clear-cell carcinoma at local hospital but later confirmed as cervical adenosquamous carcinoma by a multidisciplinary team. Three months posttreatment, she succumbed to multiple tumor metastases. The infant was healthy at the latest 2-year follow-up.

Obstetricians should expand differential diagnoses when obstetric factors cannot explain symptoms of persistent vaginal bleeding during pregnancy. Atypical and insidious clinical presentations are often concealed by physio

Core Tip: Timely and precise diagnosis and management of advanced cervical cancer in pregnancy remain challenging, with limited reports available. We describe a case of advanced-stage cervical cancer initially misdiagnosed after cesarean section, leading to an adverse maternal outcome. Accurate pathological assessment and multidisciplinary collaboration are crucial for timely diagnosis and optimal management. This case highlights the importance of vigilance in diagnosis to improve maternal outcomes and prevent treatment delays.

- Citation: Liu XJ, Wang P, Yang KX, Wang QL. Misdiagnosis and fatal outcome of advanced cervical adenosquamous carcinoma in pregnancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(34): 114352

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i34/114352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i34.114352

Cervical cancer in pregnancy (CCIP), also termed cervical cancer associated with pregnancy, is defined as a tumor present during pregnancy, puerperium, and 6 months postpartum[1]. CCIP is rare, with an incidence of 1.4-4.6 per 100000 pregnancies[2]. The clinical manifestations are atypical, easily confused with pregnancy-associated diseases, often concealed by physiological pregnancy changes, and easily misdiagnosed. Consensus and guidelines on the optional treatment of CCIP were established recently and are mainly based on limited data from a few cases and expert opinions[2]. Advanced-stage CCIP is an extremely rare but serious complication of pregnancy that is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as maternal death.

The diagnosis and management of CCIP presented unique and multifactorial challenges compared with non-pregnant patients[3-5]. The reason lies in non-specific symptoms masked by pregnancy[3,4], hormone-induced cytologic and histologic alterations[2,3], and restricted use of diagnostic modalities[3]. Managing CCIP is exceptionally complex because clinicians must simultaneously consider maternal prognosis, fetal well-being, and ethical constraints[2]. Herein, we present a case of specific diagnostic pitfall, which was misdiagnosis and fatal outcome of advanced cervical adeno

A 30-year-old female patient (gravida 1, para 1) was diagnosed with intrauterine pregnancy by ultrasonography at 7 gestational weeks. Intermittent spotting and pale pink excreta starting at 30 weeks of gestation.

The color Doppler ultrasonography examination during the first trimester, at 12 weeks of gestation, showed a myoma in the posterior wall of the uterus, measuring 3.7 cm × 3.1 cm × 3.1 cm. She received regular antenatal care and showed normal nuchal translucency, low risk on Down’s screening, and a normal oral glucose tolerance test result at a local hospital. At 23 weeks, color Doppler ultrasonography indicated a single viable fetus with no structural anomalies and normal amniotic fluid volume. The placenta was attached to the bottom of the uterus, and there was no abnormality in its appearance or location. At approximately 30 weeks, she experienced minor intermittent, irregular vaginal bleeding, accompanied by irregular abdominal tightness and firmness at night. During a routine prenatal visit at 32 weeks of gestation, a gynecologic pelvic examination revealed cervical hypertrophy, cervical ectropion, and cervical contact bleeding. Routine laboratory examinations showed no major abnormalities. Routine color Doppler ultrasonography examination showed that the fetus was well developed, but the myoma at the uterine posterior wall near the cervix had grown to approximately 6.1 cm × 5.0 cm, for which a local doctor recommended observation and rest. The patient presented at 35 weeks of gestation with a sudden gush of fluid, redness, and no uterine contractions and was hospitalized with a diagnosis of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) with a Bishop score of 3 points. The patient did not experience onset of labor after PPROM; oxytocin was administered for labor induction, and cefoxitin was admin

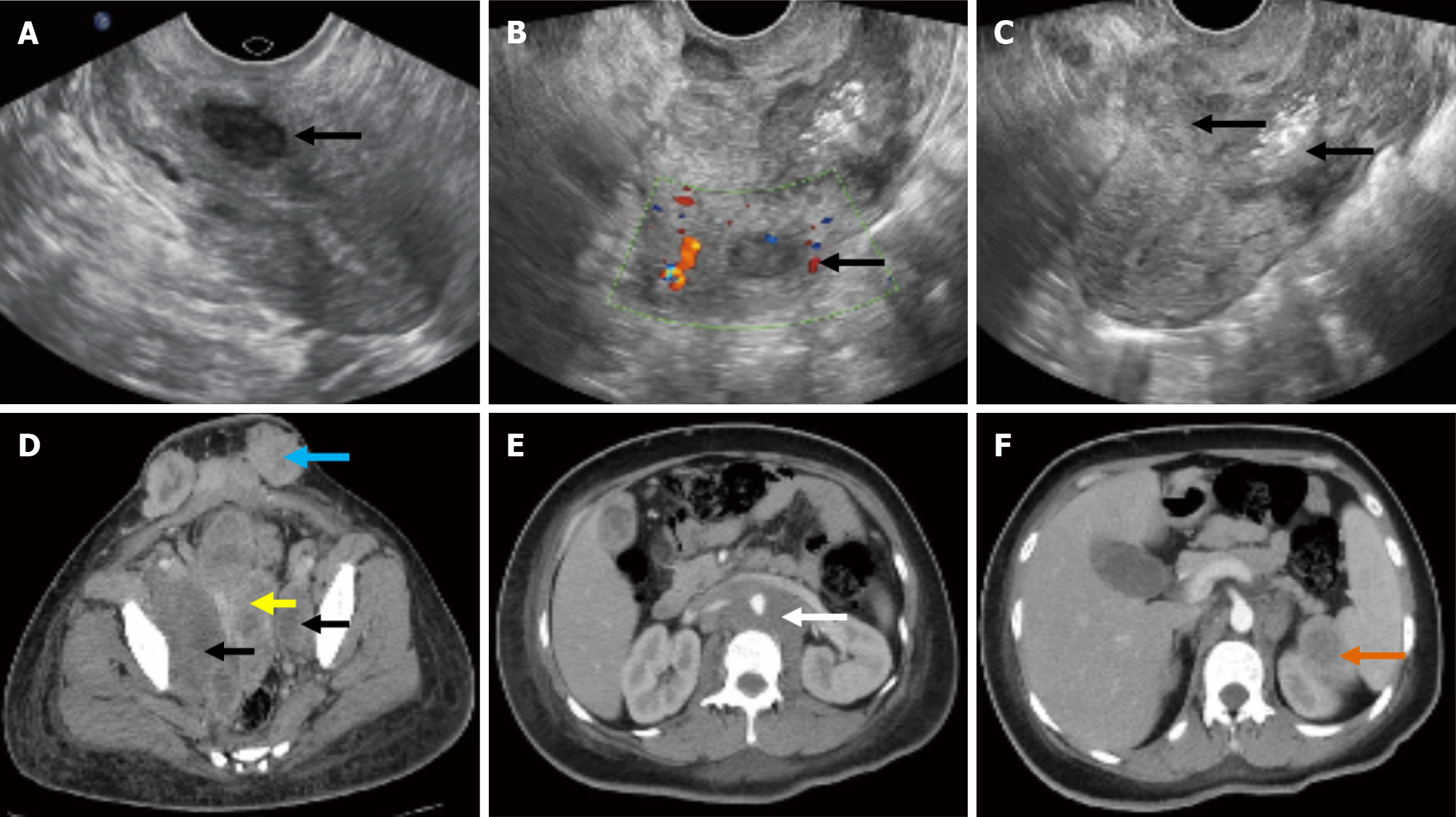

The patient had a pre-pregnancy examination 11 months prior to this pregnancy. ThinPrep cytologic test (TCT) and human papillomavirus (HPV) test results were negative. Transvaginal Ultrasonography revealed that the intramural uterine myoma was approximately 1.5 cm in diameter and located in the inferior-posterior wall of the uterus (Figure 1A).

Her menstrual, surgical, and family history was unremarkable.

One month after a cesarean section, when the patient developed a large amount of vaginal discharge after receiving chemotherapy at a local hospital, a gynecological oncologist from our hospital performed a thorough physical examination. Visual inspection revealed a barrel-shaped cervix. A gynecological pelvic examination revealed that the uterus was significantly enlarged, tumors invaded the fornix, and the parametrial tissue was thickened and hardened.

After delivery, serum tumor marker tests were performed, and the results revealed that the level of cancer antigen (CA) 125 was 244.5 U/mL and that of CA199 was 444.1 U/mL, while squamous cell carcinoma antigen, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen, alfa fetoprotein (AFP), and CA15-3 were negative.

Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed the intramural uterine myoma have not changed (Figure 1B), and an uneven, weak-echo mass of approximately 5 cm in diameter in the inferior uterine segment and cervical canal that invaded the entire layer of the muscle wall (Figure 1C). An enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of a large mass, measuring 5.2 cm × 5.6 cm × 2.6 cm, located in the cervix and middle and lower uterine cavity (Figure 1D). The tumor involved the upper one-third of the vagina and the entire myometrium and broke through the uterine serous layer. Both the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes showed metastases. Meanwhile, the tumor metastasized to paracolic sulci, subcutaneous tissue of the scar area of the abdominal wall, spleen, and left subclavian lymph nodes (Figure 1E and F).

A multidisciplinary team (MDT) consisting of specialists in gynecology, pathology, oncology, maternal-fetal medicine, radiology, ultrasonography, and palliative care convened to discuss this case. The patient was diagnosed with stage IIIC cancer, according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) (2018) classification system. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy was recommended, and surgery was ruled out.

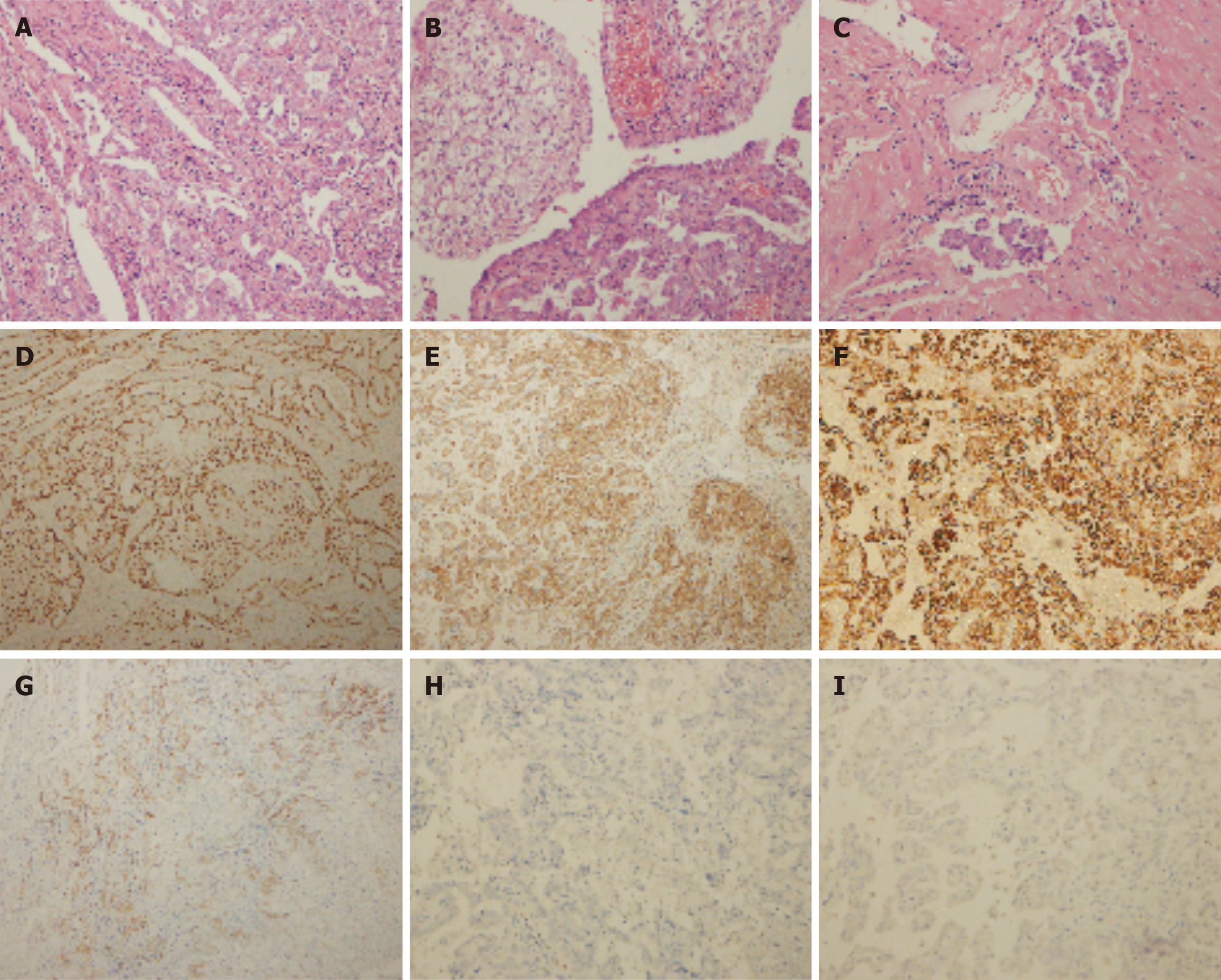

Histological examination revealed that the tumor was an adenosquamous carcinoma of cervix rather than uterine clear-cell carcinoma (CCC) that had invaded the uterine wall, and the carcinoma thrombus had permeated the muscular wall vessel by expert pathologists at our hospital. Glycogen-rich adenosquamous carcinoma can exhibit clear or vacuolated cytoplasm on hematoxylin–eosin staining due to glycogen depletion, closely resembling the “clear-cell” morphology of CCC (Figure 2A-C). Extensive pathological examination of the placenta and umbilical cord revealed no metastasis of maternal malignancy. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining demonstrated that the tumor cells were positive for hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)-1β, epithelial membrane antigen, p16, cytokeratin (CK) 7, vimentin, CK18, β-catenin, CK5/6, insulin-like growth factor-II mRNA-binding protein 3, CA125, and a mutant-type P53 immunostaining pattern, and all tumor cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, GATA binding protein 3, AFP, α-inhibin, P63, sall-like protein 4, placental alkaline phosphatase, Lin-28 homologue A, human placental lactogen, hCG, CD146, CK20, Wilms tumor protein-1, and NapsinA (Figure 2D-I); the Ki67 proliferative index was approximately 90%. The tumor had a positive DNA result for HPV16.

Postoperative pathologic examination revealed CCC of the solid mass in the uterine intramural cavity, and the patient was readmitted to the local hospital 1 month after the cesarean section for chemotherapy with intravenous paclitaxel and carboplatin. The patient was admitted to our hospital with massive and consistent active vaginal bleeding 13 days after chemotherapy. She received multiple blood transfusions for severe anemia. Bilateral uterine artery embolization was performed immediately, which eventually stopped the profuse vaginal bleeding.

The patient exhibited symptoms such as persistent high fever and general pain. Her general condition rapidly deteriorated, and she was unable to withstand subsequent treatments. The tumor marker levels were progressively elevated, and abnormal signals on enhanced CT examination was detected in multiple locations, including the intrapelvic and bilateral paracolic vessels, paracolic sulci, subcutaneous tissue of the scar area of the abdominal wall, spleen, and left subclavian lymph nodes, suggesting metastasis. Unfortunately, 3 months after treatment, the patient succumbed to multiple distant tumor metastases, leading to severe infection and systemic multiple organ failure. Despite this tragic outcome, the infant was discharged in a healthy condition. The infant underwent a 2-year follow-up and is currently in good health without any complications or tumor metastasis.

The clinical manifestations of CCIP are atypical, easily confused with pregnancy-related diseases, easily concealed by pregnancy status, and difficult to diagnose. Pregnant women often neglect prenatal examinations, which makes tumor detection difficult[3]. The early stages of cervical cancer are asymptomatic. Vaginal bleeding is the main complaint, which might often be mistaken for potential miscarriage or misdiagnosed as premature labor or placenta previa when the patient visits the clinic in mid or late pregnancy[4]. Physiological changes during pregnancy can delay the proper investigation of an underlying neoplasm[6]. In the present case, the patient experienced minor irregular vaginal bleeding at 30 weeks of gestation. The local obstetrician thought that this was a normal physiologic change during pregnancy and did not perform further examinations, such as magnetic resonance imaging, TCT and HPV test, colposcopy, or biopsy.

An accurate pelvic examination, including speculum and bimanual examination, is necessary, regardless of the gestational age. The cervical size, shape, and consistency were assessed during the bimanual examination. In the presence of pregnancy symptoms that cannot be explained by obstetric causes (e.g., irregular vaginal bleeding), the differential diagnosis should be expanded to consider the possibility of a cervical neoplasm. Biopsies performed during colposcopic examinations are considered safe for the fetus in all trimesters and reliable for diagnosis[7]. Therefore, obstetricians should pay close attention to vaginal bleeding and discharge during pregnancy and perform vaginal examinations promptly to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. When indicated, liquid-based cytology examination and colposcopy are performed as routine examinations for diagnosing pre-invasive lesions during pregnancy. If early cytology or colposcopy results are unsatisfactory, these can be repeated during the third trimester of pregnancy.

However, the diagnosis of gynecologic malignancies during pregnancy is very difficult and depends mainly on pathologic examinations. The misdiagnosis in this case resulted primarily from overlapping histomorphologic and immunophenotypic features between glycogen-rich SCC and CCC, compounded by pregnancy-related cellular alterations. Glycogen-rich SCC can exhibit clear or vacuolated cytoplasm on hematoxylin–eosin staining due to glycogen depletion, closely resembling the “clear-cell” typical morphology of CCC. However, true CCC usually shows hobnail cells, tubulocystic and papillary architecture, and frequent hyalinized stromal cores, whereas glycogen-rich SCC lacks these structural hallmarks and shows intercellular bridges and focal keratinization. In our case, limited sampling and tumor heterogeneity led to the absence of these hallmark features. CCC typically shows HNF-1β (+), Napsin A (+), p16(–), and diffuse p53 aberration; in contrast, adenosquamous carcinoma demonstrates strong p16(+), p53 wild-type pattern, and high Ki-67 (> 80%), consistent with HPV-driven cervical carcinoma. Our specimen exhibited p16 positivity, p53 wild-type staining, high Ki-67, and HPV16 DNA positivity, supporting a diagnosis of cervical rather than endometrial origin. The focal HNF-1β positivity likely reflected nonspecific expression in adenosquamous differentiation rather than a true Müllerian-type CCC phenotype[8].

Under the influence of high estrogen and progesterone levels during pregnancy, morphologic changes in tumor cells are often atypical. Pregnancy has various effects on benign conditions that may mimic malignancies, presenting challenges in the diagnosis of the pathologic types of malignant tumors[9]. During pregnancy, the increase of estrogen and progesterone leads to the displacement of the squamous column junction, glandular hyperplasia, basal-cell proliferation, and the enlargement and irregularity of the cell nucleus, making it easy for cytological examination to mis

For pregnant women with advanced cervical cancer, as in this case, a unified treatment plan is currently lacking, and the principle of individualized treatment by a MDT should be followed[11]. When a large cervical mass is accidentally discovered during cesarean section, immediate frozen-section consultation and intraoperative communication among obstetrics, pathology, and gynecologic oncology are essential. If the initial pathology report appears clinically inconsistent, an automatic MDT review should be convened. Moreover, the members of the MDT must be senior experts with rich clinical experience. The process should involve re-evaluation of clinic presentation, slides, imaging, and tumor markers before initiating treatment.

Further treatment strategies are required according to the gestational stage at the time of diagnosis, tumor stage, histopathological type, fetal viability and growth, and the patient’s wishes concerning continuation vs termination of pregnancy, which need to consider both maternal and fetal conditions. Previous studies have reported that neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is the only strategy to preserve pregnancy and achieve fetal maturity in advanced stages of cervical cancer[4,12]. Radiation therapy is not routinely recommended during pregnancy because of potential risks, including spontaneous abortion, congenital malformations, and pediatric malignancies[13]. Satisfactory tumor responses in pregnant women with locally advanced cancer have been reported, with complete or partial response after NACT[14]. Chemotherapy during the second and third trimesters is considered relatively safe but recommended to be discontinued 3 weeks before the expected delivery date or after ≥ 35 weeks of gestation to reduce hematologic risk to the fetus[6,15]. If the pregnancy is ≥ 34 weeks and fetal lung maturity is expected: A cesarean section is planned as soon as possible, and a standard concurrent radiochemotherapy is initiated within 2 weeks to 4 weeks[2]. National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline insighted that in non-pregnant patients, stage II–III–IVA cervical cancer is treated with definitive concurrent chemoradiation as the treatment of choice[16]. For a FIGO IIIC cervical cancer diagnosed at 35 weeks’ gestation with a near-term fetus, the preferred strategy is immediate delivery (usually cesarean section) followed by standard definitive chemoradiation, rather than NACT[17].

Patients with poor prognosis were reported to be more likely to have an advanced-stage disease at the time of diagnosis[18], possibly due to the increased metabolism in pregnancy, hyperdynamic circulation, rich uterine blood supply, increased estrogen-progesterone levels, and altered immunologic function[19]. To our knowledge, surgical extrusion may lead to tumor spread, which is closely related to the timing and surgical incision selection. These factors can accelerate the proliferation of tumor cells, which may metastasize through the pelvic lymph and blood circulation, as in this case. Therefore, more active management is needed for patients with CCIP to improve their prognosis.

Based on this case, we propose several recommendations. First, although cervical cancer was detected after cesarean section, it was present during pregnancy; therefore, more attention needs to be paid to the impact of physiological changes during pregnancy. Endometrial carcinoma is rarely associated with pregnancy because it is a state of naturally increased progesterone levels, which act protectively on the endometrium. Second, pathologists should focus on cell morphology and IHC marker results and carefully consider the medical history, clinical presentation, imaging, and serum tumor marker results, which are crucial for making an accurate pathologic diagnosis. Finally, highly experienced pathologists must decide who can examine and draw a conclusion from the film to reduce misdiagnoses.

The identification and management of CCIP remain challenging. This case serves to remind obstetricians of the necessity for a broad differential diagnosis when symptoms of abnormal vaginal bleeding are encountered that cannot be explained by obstetric factors. Owing to physiologic changes in pregnancy, the lack of typicality from laboratory testing to microscopic cytologic morphology greatly increases the difficulty of diagnosis. This case serves to remind pathologist that pathological diagnosis of pelvic masses in pregnancy must integrate clinical presentation, hormonal status, imaging findings, and IHC results. Glycogen-rich squamous carcinomas are prone to misclassification as CCC, and HPV status with p16 expression are critical discriminators. Management requires “a delicate balance between maternal benefit and fetal risk”, achieved through individualized, multidisciplinary decision-making. Implementing a mandatory, efficient MDT consultation mechanism is fundamental to preventing such tragic outcomes.

We thank the patient for participation and her family for facilitating the clinical reports preparation.

| 1. | Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Mayr N, Anderson B, Buller RE, Niebyl J. Cervical cancer diagnosed shortly after pregnancy: prognostic variables and delivery routes. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:832-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Amant F, Berveiller P, Boere IA, Cardonick E, Fruscio R, Fumagalli M, Halaska MJ, Hasenburg A, Johansson ALV, Lambertini M, Lok CAR, Maggen C, Morice P, Peccatori F, Poortmans P, Van Calsteren K, Vandenbroucke T, van Gerwen M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, Zagouri F, Zapardiel I. Gynecologic cancers in pregnancy: guidelines based on a third international consensus meeting. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1601-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beharee N, Shi Z, Wu D, Wang J. Diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer in pregnant women. Cancer Med. 2019;8:5425-5430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li M, Zhao Y, Qie M, Zhang Y, Li L, Lin B, Guo R, You Z, An R, Liu J, Zhang Z, Bi H, Hong Y, Chang S, He G, Hua K, Zhou Q, Liao Q, Wang Y, Wang J, Li X, Wei L. Management of Cervical Cancer in Pregnant Women: A Multi-Center Retrospective Study in China. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:538815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Halaska MJ, Uzan C, Han SN, Fruscio R, Dahl Steffensen K, Van Calster B, Stankusova H, Marchette MD, Mephon A, Rouzier R, Witteveen PO, Vergani P, Van Calsteren K, Rob L, Amant F. Characteristics of patients with cervical cancer during pregnancy: a multicenter matched cohort study. An initiative from the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hepner A, Negrini D, Hase EA, Exman P, Testa L, Trinconi AF, Filassi JR, Francisco RPV, Zugaib M, O'Connor TL, Martin MG. Cancer During Pregnancy: The Oncologist Overview. World J Oncol. 2019;10:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | La Russa M, Jeyarajah AR. Invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;33:44-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Němejcová K, Cibula D, Dundr P. Expression of HNF-1β in cervical carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study of 155 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Haan J, Vandecaveye V, Han SN, Van de Vijver KK, Amant F. Difficulties with diagnosis of malignancies in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;33:19-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Félix A, Nogales FF, Arias-Stella J. Polypoid endometriosis of the uterine cervix with Arias-Stella reaction in a patient taking phytoestrogens. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2010;29:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kurniadi A, Setiawan D, Kireina J, Suardi D, Salima S, Erfiandi F, Andarini MY. Clinical and Management Dilemmas Concerning Early-Stage Cervical Cancer in Pregnancy - A Case Report. Int J Womens Health. 2023;15:1213-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Perrone AM, Bovicelli A, D'Andrilli G, Borghese G, Giordano A, De Iaco P. Cervical cancer in pregnancy: Analysis of the literature and innovative approaches. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:14975-14990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chen G, Huang K, Sun J, Yang L. Cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma in the third trimester: a rare case report and literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Guo Y, Zhang D, Li Y, Wang Y. A case of successful maintained pregnancy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery for stage IB3 cervical cancer diagnosed at 13 weeks. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wolters V, Heimovaara J, Maggen C, Cardonick E, Boere I, Lenaerts L, Amant F. Management of pregnancy in women with cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:314-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, Barber E, Bradley K, Brooks R, Campos SM, Chino J, Chon HS, Crispens MA, Damast S, Fisher CM, Frederick P, Gaffney DK, Gaillard S, Giuntoli R, Glaser S, Holmes J, Howitt BE, Lea J, Mantia-Smaldone G, Mariani A, Mutch D, Nagel C, Nekhlyudov L, Podoll M, Rodabaugh K, Salani R, Schorge J, Siedel J, Sisodia R, Soliman P, Ueda S, Urban R, Wyse E, McMillian NR, Aggarwal S, Espinosa S. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Cervical Cancer, Version 1.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:1224-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cibula D, Raspollini MR, Planchamp F, Centeno C, Chargari C, Felix A, Fischerová D, Jahnn-Kuch D, Joly F, Kohler C, Lax S, Lorusso D, Mahantshetty U, Mathevet P, Naik R, Nout RA, Oaknin A, Peccatori F, Persson J, Querleu D, Bernabé SR, Schmid MP, Stepanyan A, Svintsitskyi V, Tamussino K, Zapardiel I, Lindegaard J. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP Guidelines for the management of patients with cervical cancer - Update 2023. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33:649-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 99.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bigelow CA, Horowitz NS, Goodman A, Growdon WB, Del Carmen M, Kaimal AJ. Management and outcome of cervical cancer diagnosed in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:276.e1-276.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Xia T, Gao Y, Wu B, Yang Y. Clinical analysis of twenty cases of cervical cancer associated with pregnancy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:1633-1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/