Published online Oct 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i28.109536

Revised: June 4, 2025

Accepted: July 4, 2025

Published online: October 6, 2025

Processing time: 85 Days and 6.8 Hours

Uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis are exceptionally rare in adolescents and can pose significant diagnostic challenges due to their nonspecific clinical presentation and imaging features, which may mimic malignancy. Here, we describe a case of adenomyosis-associated uterine rupture (secondary to hemorrhagic necrosis) and concurrent pulmonary endometriosis in a 16-year-old girl initially suspected of having advanced uterine cancer.

A 16-year-old girl presented with acute abdominal pain and oliguria. Imaging studies revealed a 15-cm ruptured uterine mass accompanied by hemoperitoneum and multiple pulmonary nodules suggestive of metastatic disease. Laboratory tests demonstrated severe anemia and markedly elevated tumor markers [cancer antigen (CA)-125: 1063 U/mL; CA-19-9: 1347 U/mL]. Emergency laparotomy revealed adenomyosis-associated uterine rupture secondary to hemorrhagic necrosis, with no macroscopic abnormalities in other organs. A total abdominal hysterectomy was performed. Histopathological analysis confirmed uterine ade

This case of an adolescent patient highlights how benign gynecological conditions can mimic malignancy, necessitating broad differential diagnoses despite alarming presentations.

Core Tip: This case underscores the considerable diagnostic challenges associated with rare presentations of uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis in adolescent patients. The clinical overlap with malignancy underscores the need for a high index of suspicion and a multidisciplinary approach to ensure accurate diagnosis and timely intervention. As demonstrated here, early surgical management combined with appropriate postoperative medical therapy can lead to favorable outcomes, even in the context of severe and atypical diseases. This case reinforces the necessity of including benign etiologies in the differential diagnosis of presumed advanced-stage malignancies, particularly in young female patients.

- Citation: Ju UC, Kang WD, Kim SM. Adenomyosis-associated uterine rupture and pulmonary endometriosis mimicking advanced-stage uterine malignancy in an adolescent female: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(28): 109536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i28/109536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i28.109536

Adenomyosis is a prevalent gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma extending beneath the endomyometrial interface and deeply infiltrating the myometrium, whereas endometriosis is defined by the ectopic presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity[1,2]. Both conditions commonly present with nonspecific symptoms such as dysmenorrhea and chronic pelvic pain. Acute manifestations of the uterine adenomyosis—including uterine rupture and massive hemoperitoneum—are exceedingly uncommon[3]. Necrotizing rupture of adenomyosis, a life-threatening complication, has been sporadically documented in the context of trauma, infection, or spontaneous degeneration; however, reports in adolescent patients are virtually nonexistent. Although endometriosis is most often confined to the pelvic region, ectopic endometrial tissue has also been identified in extrapelvic sites, such as the umbilicus, abdominal scars, breasts, extremities, pleural cavity, and lungs[4-7]. Pulmonary endometriosis, a rare form of extrapelvic endometriosis, poses significant diagnostic challenges due to its nonspecific respiratory symptoms and is especially uncommon in adolescent populations. Its clinical presentation may closely resemble that of metastatic malignancy, thereby complicating diagnostic evaluation.

The concurrent occurrence of uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis in a single patient is exceptionally rare, and to our knowledge, no such case has been previously reported in the English-language literature involving an adolescent girl. Herein, we describe a unique case of a 16-year-old girl with adenomyosis-associated uterine rupture (secondary to hemorrhagic necrosis) and concurrent pulmonary endometriosis who was initially suspected to have advanced-stage uterine malignancy.

Abdominal pain and oliguria.

A 16-year-old nulligravid and nulliparous girl presented to the emergency department of our institution in June 2022 with abdominal pain and oliguria. There were no other symptoms, such as hemoptysis.

She had no relevant medical or surgical history.

She had no notable menstrual abnormalities other than moderate dysmenorrhea.

A tender mass was palpated below the umbilicus. Her vital signs were unstable, with a blood pressure of 60/40 mmHg, a heart rate of 140/minute, and a body temperature of 36.0 °C.

Laboratory tests revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin, 6.2 g/dL) and marked leukocytosis (25900/μL). Inflammatory and tumor markers were elevated, including C-reactive protein at 28.2 g/dL (reference range: 0-0.3 g/dL), lactate dehydrogenase at 1476 U/L (reference range: 218-472 U/L), cancer antigen (CA)-125 at 1063 U/mL (reference range: 0-35 U/mL), and CA-19-9 at 1347 U/mL (reference range: 0-37 U/mL).

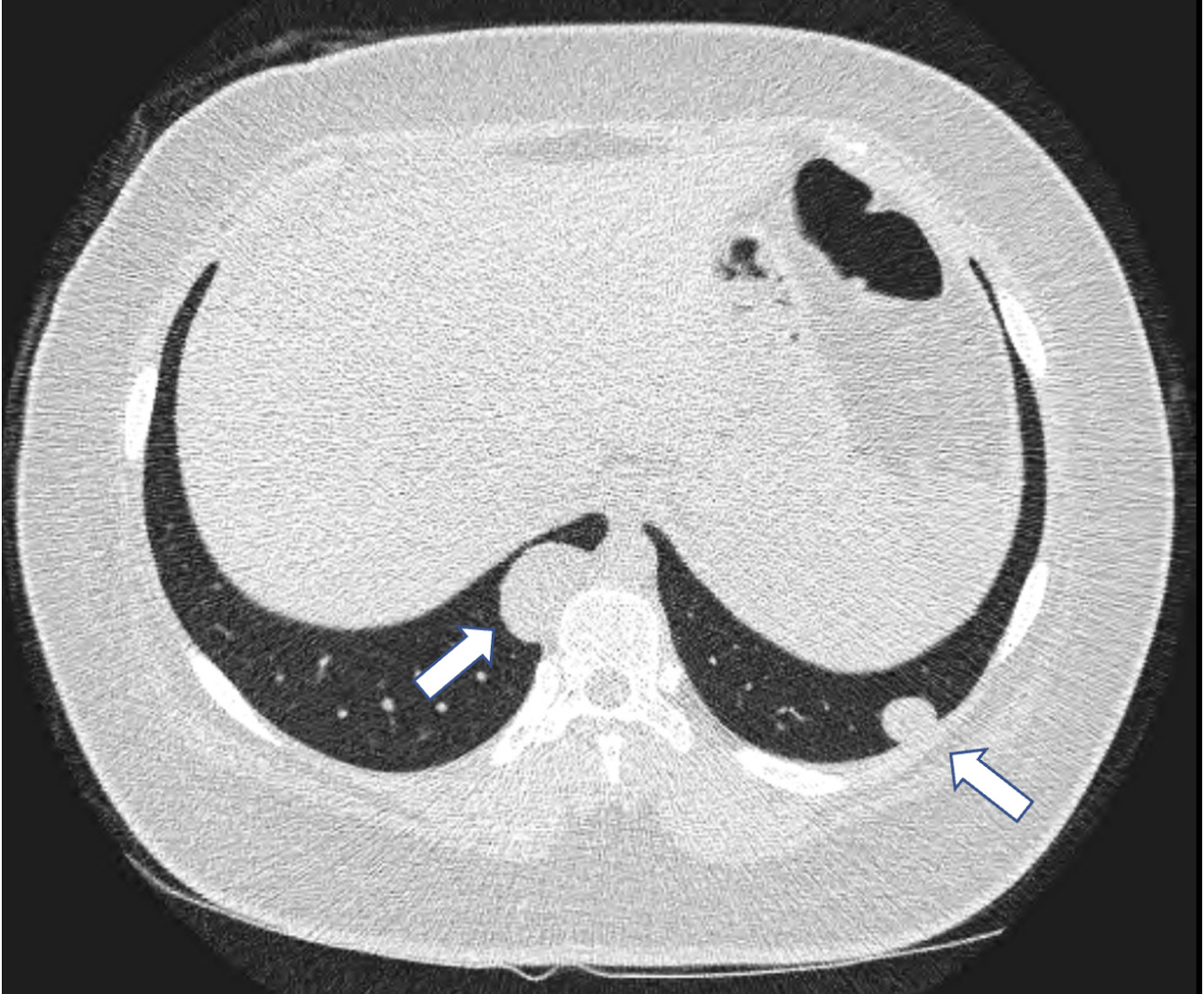

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 15-cm ruptured uterine mass accompanied by massive hemoperitoneum. While receiving transfusions of packed red blood cells, the patient underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging and chest CT (Figures 1 and 2). The findings of these imaging investigations suggested a ruptured uterine malignancy and multiple pulmonary nodules highly suspicious for metastatic disease. No abnormalities were noted in other organs, and no lymphadenopathy was detected. Due to the patient’s hemodynamic instability and the high suspicion of an aggressive uterine malignancy, we had no choice but to proceed with an emergency surgical intervention.

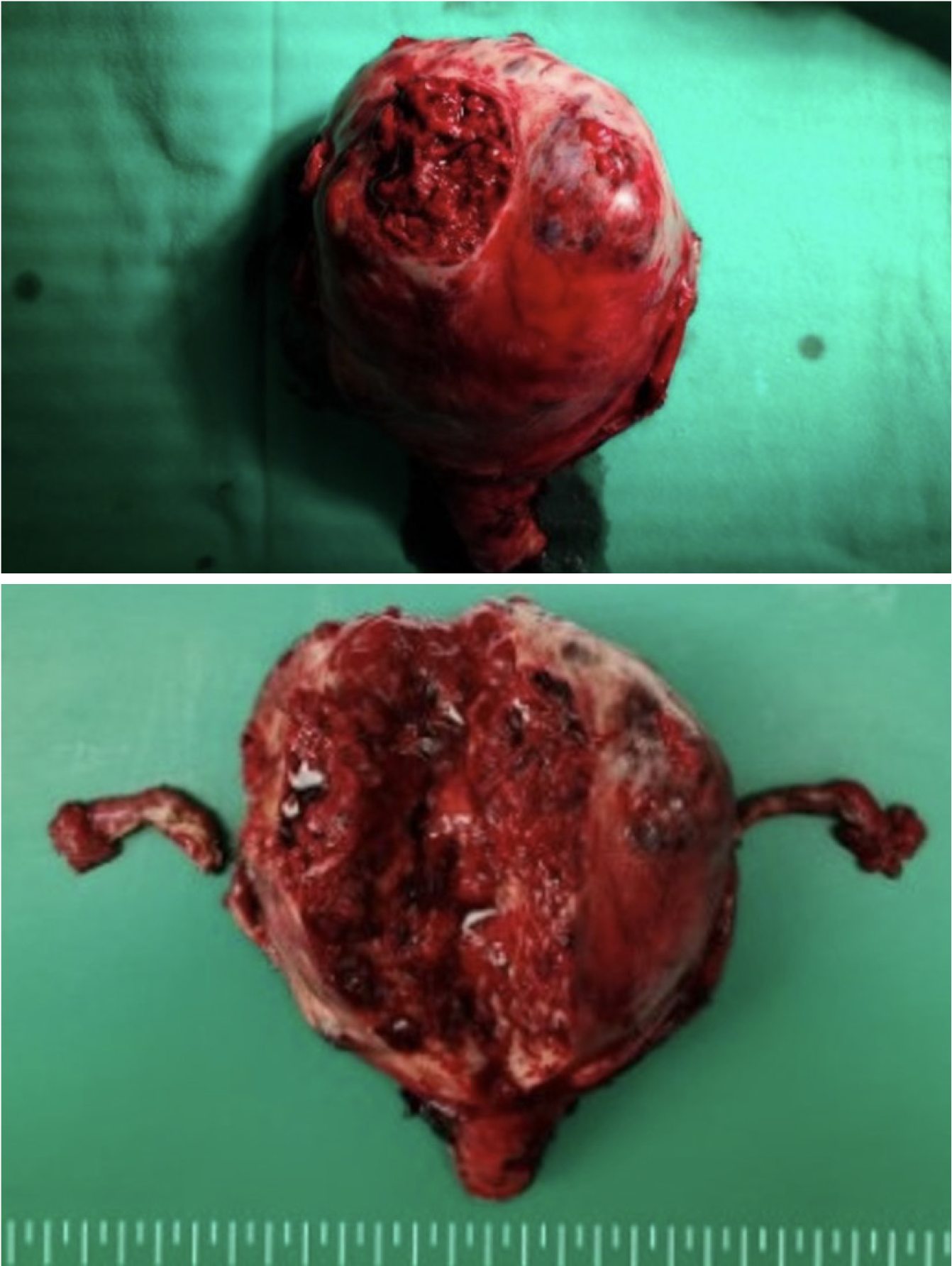

Histopathological examination confirmed uterine adenomyosis with hemorrhagic necrosis and pulmonary endometriosis with associated hemorrhage. The uterine lesion showed extensive hemorrhagic necrosis of adenomyotic foci, while the pulmonary nodules demonstrated endometrial glands, stroma, and hemosiderin-laden macrophages, confirming ectopic endometrial tissue (Figure 3).

Owing to persistent hemodynamic instability despite transfusions, an emergency laparotomy was performed. Intraoperative findings included a completely necrotic and massively enlarged (15 cm) uterus with multiple perforations and hemoperitoneum of approximately 4 L. The remaining abdominal organs, including both ovaries, appeared grossly normal, and no palpable lymphadenopathy was observed. Given the severity of uterine necrosis and the impossibility of uterine preservation, a total abdominal hysterectomy was performed despite the patient’s young age.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered well, requiring a 1-day stay in the intensive care unit and an additional 5 days in the general ward. On postoperative day 7, she underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resections for bilateral pulmonary nodules (3.5 cm in the right lower lobe and 1.5 cm in the left lower lobe).

Following surgery, serum CA-125 and CA-19-9 levels decreased to 108 U/mL and 67 U/mL, respectively. The patient was prescribed oral dienogest at 2 mg daily for the prevention of recurrent pulmonary endometriosis. Follow-up abdominal and chest CT performed 6 months later revealed no abnormalities, and serum tumor marker levels remained within normal limits. At 3 years postoperatively, the patient was asymptomatic with no evidence of recurrence on imaging, and is currently leading a normal life.

This case describes an exceptionally rare clinical presentation in a 16-year-old nulliparous adolescent: (1) Adenomyosis-associated uterine rupture secondary to hemorrhagic necrosis; and (2) Accompanied by pulmonary endometriosis—initially misinterpreted as advanced-stage uterine malignancy with pulmonary metastases. Adenomyosis is rare in adolescents and typically affects women of reproductive age. Rupture of adenomyosis, particularly with necrotizing features, represents an exceedingly uncommon complication. The clinical manifestations of uterine rupture secondary to necrotic adenomyosis are poorly characterized in the literature, especially among adolescent patients[3]. Most documented cases of uterine rupture are associated with pregnancy or a history of uterine surgery, neither of which was present in this patient. Similarly, pulmonary endometriosis constitutes a rare extrapelvic manifestation of endometriosis, with fewer than 100 cases reported over the past 2 decades, predominantly in women older than 20 years[6]. The concurrent presentation of these two pathologies in a teenager, along with a life-threatening clinical course, distinguishes this case as a unique and noteworthy contribution to the medical literature.

Uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis are exceedingly uncommon in adolescents, and accurate diagnosis necessitates comprehensive clinical, radiological, and histopathological assessment. In this case, the diagnosis was particularly challenging due to an aggressive initial presentation suggestive of advanced-stage uterine malignancy. Elevated tumor markers, extensive uterine rupture, and pulmonary nodules raised substantial concern for disseminated malignant disease.

The marked elevation of both CA-125 and CA-19-9 further complicated the diagnostic process. CA-125 and CA-19-9 were measured as part of the initial malignancy workup given the large pelvic mass with hemorrhagic features and suspicion for gynecologic cancer. While these tumor markers are commonly used for the evaluation of gynecological malignancies, they may also be elevated in benign gynecological conditions such as adenomyosis and endometriosis[8,9]. The precise pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these increases remain unclear but are thought to involve inflammatory responses, extensive tissue destruction, and peritoneal irritation. This case underscores the importance of interpreting tumor marker data within the broader clinical and imaging context, rather than relying on serological findings in isolation.

Another notable diagnostic challenge involved the identification of pulmonary nodules, which were initially presumed to represent metastatic disease. Pulmonary endometriosis, a rare component of thoracic endometriosis syndrome, is typically associated with catamenial pneumothorax or hemoptysis[5,6,10]. In this patient, however, the pulmonary lesions remained asymptomatic and were detected incidentally during staging imaging. A definitive diagnosis was established following surgical resection and histopathological analysis, which confirmed the presence of hemorrhagic endometriotic implants in the absence of malignancy. This finding emphasizes the need to include benign thoracic etiologies in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary nodules, particularly in patients with known or suspected gynecological pathologies.

Surgical intervention was imperative owing to the extensive uterine necrosis and the resultant hemodynamic instability. Although total abdominal hysterectomy is an extraordinary and irreversible intervention in a 16-year-old patient, it was deemed lifesaving in this context. Intraoperative findings confirmed the impossibility of uterine preservation owing to diffuse necrosis and perforation, thus necessitating definitive surgical management to prevent ongoing hemorrhage and mortality.

Postoperatively, hormonal suppression therapy with dienogest was initiated to reduce the risk of endometriosis recurrence and manage potential residual symptoms[11,12]. Dienogest, a selective progestin, has demonstrated clinical effectiveness in reducing endometriotic lesions and controlling pain[13,14]. Given the rarity and complexity of this presentation, long-term surveillance is warranted to monitor the recurrence or emergence of new lesions.

This case offers several important clinical insights. First, both uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis, although rare in adolescents, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of young female patients presenting with complex gynecological and thoracic findings. Second, elevated tumor markers (e.g., CA-125 and CA-19-9) must be interpreted with caution, as they may be elevated in both benign and malignant gynecological conditions. Third, it should not be presumed that the presence of pulmonary nodules indicates metastatic disease without histopathological confirmation. Finally, prompt surgical intervention may be lifesaving in cases of uterine rupture, even in the absence of classic risk factors such as pregnancy or prior uterine surgery.

Further research is warranted to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying adenomyosis-related uterine rupture and to identify risk factors in adolescent populations. Improved clinical awareness and detailed documentation of similar cases may facilitate earlier diagnosis and timely management of this rare, yet potentially life-threatening, presentation.

This case underscores the considerable diagnostic challenges associated with rare presentations of uterine adenomyosis and pulmonary endometriosis in adolescent patients. The clinical overlap with malignancy underscores the need for a high index of suspicion and a multidisciplinary approach to ensure accurate diagnosis and timely intervention. As demonstrated here, early surgical management combined with appropriate postoperative medical therapy can lead to favorable outcomes, even in the context of severe and atypical disease. Importantly, this case reinforces the necessity of including benign etiologies in the differential diagnosis of presumed advanced-stage malignancies, particularly in young female patients.

| 1. | Bird CC, McElin TW, Manalo-Estrella P. The elusive adenomyosis of the uterus--revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;112:583-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Erguvan R, Meydanli MM, Alkan A, Edali MN, Gokce H, Kafkasli A. Abscess in adenomyosis mimicking a malignancy in a 54-year-old woman. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2003;11:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manivannan A, Pandurangi M, Vembu R, Reddy S. Exophytic Subserosal Uterine Adenomyomatous Polyp Mimicking Malignancy: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15:e43675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hilaris GE, Payne CK, Osias J, Cannon W, Nezhat CR. Synchronous rectovaginal, urinary bladder, and pulmonary endometriosis. JSLS. 2005;9:78-82. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Huang H, Li C, Zarogoulidis P, Darwiche K, Machairiotis N, Yang L, Simoff M, Celis E, Zhao T, Zarogoulidis K, Katsikogiannis N, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Li Q. Endometriosis of the lung: report of a case and literature review. Eur J Med Res. 2013;18:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tong SS, Yin XY, Hu SS, Cui Y, Li HT. Case report of pulmonary endometriosis and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:1766-1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yao J, Zheng H, Nie H, Li CF, Zhang W, Wang JJ. Endometriosis of the lung: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:4326-4333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Anastasi E, Gigli S, Ballesio L, Angeloni A, Manganaro L. The Complementary Role of Imaging and Tumor Biomarkers in Gynecological Cancers: An Update of the Literature. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:309-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Kimura T, Miyatake T, Yoshino K, Fujita M, Kimura T. Serum biomarkers for early detection of gynecologic cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2010;2:1312-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen C, Zhai K, Tang Y, Qu W, Zuo J, Ke X, Song Y. Thoracic endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:3500-3503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zakhari A, Edwards D, Ryu M, Matelski JJ, Bougie O, Murji A. Dienogest and the Risk of Endometriosis Recurrence Following Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1503-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liu Y, Gong H, Gou J, Liu X, Li Z. Dienogest as a Maintenance Treatment for Endometriosis Following Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:652505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thiel PS, Donders F, Kobylianskii A, Maheux-Lacroix S, Matelski J, Walsh C, Murji A. The Effect of Hormonal Treatment on Ovarian Endometriomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2024;31:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Maiorana A, Maranto M, Restivo V, Gerfo DL, Minneci G, Mercurio A, Incandela D. Evaluation of long-term efficacy and safety of dienogest in patients with chronic cyclic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/