Published online Sep 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i26.100363

Revised: November 21, 2024

Accepted: June 3, 2025

Published online: September 16, 2025

Processing time: 335 Days and 4.9 Hours

Although exposure therapy is a proven treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), empirical research is difficult due to ethical issues. Recently, virtual reality-based content that can provide space and time similar to reality for exposure therapy techniques is increasing.

To examine exposure therapy using driving simulations in patients with PTSD due to traffic accidents with PTSD symptoms.

The intervention was provided to two individuals who experienced PTSD symptoms after a traffic accident using a driving simulator. Among the single-subject experimental designs, the ABA (baseline-intervention-baseline) design was used, and the PTSD checklist and brain wave frequency were used to measure the results.

In all participants, the standard category departure time of the electroencephalogram decreased from baseline, and PTSD symptoms decreased after the intervention.

These results suggest the potential use of a driving simulator as an exposure treatment tool for PTSD.

Core Tip: This study suggest the potential of using a driving simulator as an exposure treatment tool for in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to traffic accidents with PTSD symptoms.

- Citation: Jeong HW, Jung JW, Jang SH, Kim DY, Lee JY, Jang JS. Effects of driving simulator intervention on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after traffic accidents: A single-subject study. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(26): 100363

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i26/100363.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i26.100363

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that occurs after an extremely traumatic experience and is characterized by three symptoms: Hyperarousal, re-experiencing, and avoidance[1]. It is influenced by stress, the victim’s personality tendencies, and social environment. Traffic accidents occur frequently and are the most traumatic events experienced by Koreans[2]. Additionally, individuals who have experienced trauma reported traffic accidents as the most shocking among various traumatic events[3]. The number of car users is continuously increasing, and the number of traffic accidents was expected to reach 196836 or 381.3 per 100000 people by 2022[4].

The main clinical features of PTSD are repetitive traumatic thoughts accompanied by painful emotions (repeated painful images and nightmares), numbness in trauma-related responses, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, and persistence of a hyperarousal state (sleep disturbance and startleness). Moreover, PTSD is accompanied by negative emotions, such as general anxiety, depression, shame, guilt, trauma-related avoidance, and anxiety[5].

There are two treatment methods for PTSD, drug and non-drug. Antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were the primary drug treatments[6]. Recently, antidepressants with new mechanisms have been reported to be effective in treating PTSD, but most drugs are only effective against specific symptoms. Therefore, the present results of drug treatment are insufficient[7]. Non-drug treatments include psychodynamic psychotherapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, hypnotherapy, cognitive therapy, and behavioral therapy. Behavioral therapy includes biofeedback and exposure therapy[8]. Exposure therapy desensitizes patients to fear-inducing stimuli by allowing them to remain afraid for prolonged periods[6]. Although exposure therapy is an effective treatment for PTSD, empirical research is difficult because of ethical issues[9]. Accordingly, exposure therapy techniques for PTSD have been combined with virtual reality (VR)-based content, which can provide space and time similar to the real world[10,11].

Driving simulators can provide highly realistic driving situations and simultaneously provide a high possibility of controlling various variables that are essential for empirical research[12]. Additionally, driving simulators can configure various scenarios to perform tasks essential to driving, such as avoiding dangerous substances and sudden braking, without exposing the driver to danger[12,13]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of exposure therapy using driving simulations on post-traumatic stress symptoms in patients with PTSD caused by traffic accidents.

The participants in this study were those who experienced PTSD symptoms after a traffic accident and met the selection criteria below. The subject information is shown in Table 1.

| Subject A | Subject B | |

| Age (gender) | 19 (F) | 21 (F) |

| Age at the time of accident | 8 | 9 |

| Symptoms at the time of the accident | No memory; Even now, surprised at the crosswalk | Repeatedly sleeping and waking up; At first it was fine, but as time passed it hurts |

| Motivation for participation | She wants to know if her current fear of cars is due to an accident, she had as a child and, if so, if she can overcome it | She wants to get her driver's license but is worried that her trauma will affect her, so she wants to experience it first through a simulation |

Selection criteria: (1) Primary care PTSD screening for DSM-5 of ≥ 2 items; (2) Not diagnosed with any other disability; and (3) Voluntary participation (Table 2).

| Target selection; PC-PTSD-5 > 2 | ||

| ↓ | ||

| Pre-test; PCL-5-K | ||

| ↓ | ||

| Baseline (A); three sessions | - | Watch driving video + BTS-2000 |

| Intervention (B); nine sessions | Driving simulator program | |

| Baseline (A); three sessions | - | |

| ↓ | ||

| Post-test; PCL-5-K | ||

This study used a single-subject ABA experimental design comprising 15 sessions, each lasting approximately 30 min. To reduce simulator sickness of the driving simulator, a 5-minute break was allowed after the 5-minute adaptation period, and an explanation of safety was provided during the break. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee (KWNUIRB-2023-05-005-002).

During the baseline and re-baseline periods, brain waves were measured while participants watched a 5-minute driving video without any intervention. Driving videos were selected randomly by the researcher and displayed on a tablet. All videos were filmed from the driver’s perspective, and those with minimal differences in weather, traffic volume, and road conditions were selected.

During the intervention period, after driving on the simulator, brain waves were measured while the participants watched driving videos. The driving simulator course was set to normal and conducted in a situation in which other vehicles were present. The driving environment was set to clear weather and moderate traffic conditions. After driving in the simulator, the driving video was viewed in the same manner as that in the baseline.

Driving simulator: The driving simulator included three monitors that provided a 60–180° field of view to the driver, two speakers, a driver’s seat, a steering wheel control device, a pedal control device, an experimenter, and a computer. It is the most widely used driving device for people with disabilities in Korea. The road content includes the national driver’s license test and basic driving courses, reproducing the driving environment in the city center, highways, and local roads. By adjusting the weather and traffic volume, situations such as waiting at a signal, cutting into a vehicle on the shoulder, entering a turn at an intersection, and driving on a congested road can be simulated, thereby allowing simulations in various driving situations. The GDS-SEDAN-2014-D was used as a tool to safely drive in real-life situations similar to real life. Driving tests were conducted in Gangnam, Gangseo, Seobu, and Dobong, and detailed driving environments were conducted randomly.

Korean version of PTSD checklist-5: This is a self-report questionnaire developed to observe changes in PTSD symptoms in DSM-5 and comprised 20 factors and four sub-factors: “invasion”, “avoidance”, “negative changes in cognition and emotion”, and “hyperarousal”. The extent to which the symptoms caused by stressful experiences caused pain over the past month was rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much), with the total score ranging from 0 to 80. The reliability was Cronbach's α = 0.93.

Brain education system-2000: It measures and analyzes the abilities required for learning using brain waves, which are electrical signals generated in the human brain. It objectively and accurately evaluates the advanced cognitive functions involved in the learning process using neurophysiological brain wave indicators. Additionally, it can extract the response strength and timing from the frequency-domain response pattern of brain waves according to the stimulus induction and present it visually. We observed the frequencies of the brain waves and attempted to determine the degree of response to stimulation by measuring the time required to deviate from the standard range presented by the equipment.

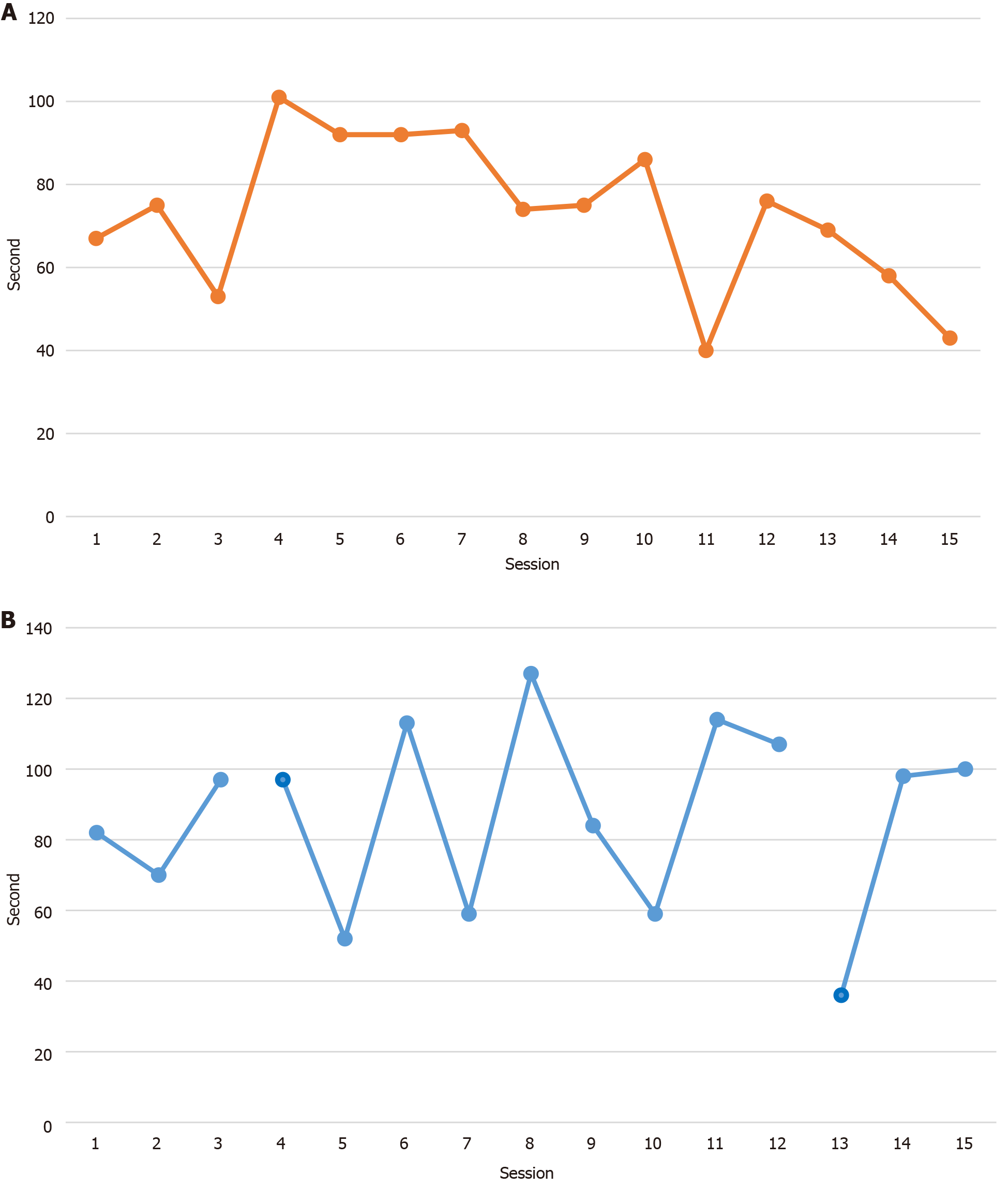

Consequent to measuring the time that the brain wave frequency deviated from the standard range while watching the driving video in each session, the time that the brain wave frequency deviated from the standard range for participant A increased at the beginning of the intervention period but tended to decrease gradually. Additionally, the baseline average decreased from 65.0 s to the re-baseline average of 56.7 s (Figure 1A).

The brain wave frequency deviation time of participant B from the standard category was observed inconsistently but decreased from the baseline average of 83.0 s to the re-baseline average of 78.0 s (Figure 1B).

The changes in PTSD symptoms after the intervention are shown in Table 3. Participant A’s total score decreased from 17 to six points. For participant B, the total score decreased from 22 to six points. The hyperarousal area showed the greatest change from eight to one point.

| Participant/Item | A | B | ||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Intrusion | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| Avoidance | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| Negative alterationin cognition and mood | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Alterations in arousal and reactivity | 9 | 4 | 8 | 1 |

| Total | 17 | 6 | 22 | 6 |

The possibility of combining VR technology with medicine is of significant interest to many academic circles, and the size of the medical market for VR technology may increase further eventually[14]. Accordingly, this study aimed to determine the effects of exposure therapy using a driving simulator on PTSD symptoms.

Regarding brain wave frequencies, the brain wave standard category departure time significantly increased in all participants during the intervention period, suggesting that the driving simulator provided sufficient stimulation for exposure therapy. Subsequently, the symptoms decreased owing to the effect of exposure. Furthermore, the effectiveness of this study was indirectly confirmed, as the deviation time from the standard range was reduced at baseline after the intervention compared with baseline. These results are similar to those of previous studies, showing that sustained exposure therapy is effective in improving the clinical symptoms of PTSD[9,15]. However, while existing studies have provided interventions using a cognitive behavioral approach, this study provides a VR intervention using a driving simulator, which appears to be a better intervention. Accordingly, the effectiveness of VR interventions using a driving simulator should be demonstrated through continuous intervention in future research.

Based on the results of the PTSD checklist-5, all participants reported experiencing PTSD symptoms that were not severe enough to be diagnosed with PTSD, even before the intervention. However, they reported feeling uncomfortable daily because of traffic accidents, and the degree of their daily PTSD symptoms appeared to decrease after the intervention. These results support the use of exposure therapy with a driving simulator in patients with PTSD symptoms.

The VR intervention used in this study can treat fearful situations by creating the illusion of being in the real world without having to face them directly[16]. However, cybersickness may occur because of the gap between the virtually realized graphic image and the real environment, and the disability that occurs when returning to the real world after the treatment process must be considered[5]. In the driving simulator, the external environment is presented on the screen, and the internal environment has the same structure as the actual vehicle; therefore, it is possible to obtain the effect of exposure therapy and minimize cybersickness. Additionally, it can be a more effective treatment tool for patients who experience a fear of car spaces. Based on these results, it is necessary to apply tools to reduce the gap between VR and real environments in future research.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the brain waves used to measure PTSD symptoms in each session are devices that respond sensitively to external stimuli, making it difficult to reduce the reliability of the participants’ results. Second, the results are difficult to generalize because the participants were not diagnosed with PTSD. Therefore, in future research, participants diagnosed with PTSD should be assessed using tools related to PTSD symptoms, such as blood pressure and breathing. However, this study revealed that exposure therapy using a driving simulator positively affected the clinical symptoms of PTSD.

We confirmed the effects of exposure therapy using a driving simulator in patients who experienced PTSD symptoms after a traffic accident. During participation in this research intervention, the participants were observed to have symptoms of exposure, which allowed us to verify the effectiveness of the exposure therapy. Additionally, all partici

| 1. | Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, Nutt DJ, Foa EB, Kessler RC, McFarlane AC, Shalev AY. Consensus statement on posttraumatic stress disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 Suppl 5:60-66. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Seo YS, Joe HJ, Ann HY, Lee JS. [Traumatic events experienced by South Koreans: types and prevalence]. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2012;24:671-701. |

| 4. | Statistics Korea. 2023. Future population projections. Available from: https://www.index.go.kr/unity/potal/indicator/IndexInfo.do?cdNo=2&clasCd=10&idxCd=F0001. |

| 5. | Kim EY. [Cognitive behavioral therapy program development and effectiveness of for the reduction of sexual trauma counselor vicarious traumatization]. M.D. Thesis, Myongji University. 2018. Available from: https://www.riss.kr/link?id=T14743402. |

| 6. | Kim W, Bae JH, Woo JM. Prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder: A case report. Cogn Behav Ther Korea. 2005;5:25-33. |

| 7. | Asnis GM, Kohn SR, Henderson M, Brown NL. SSRIs versus non-SSRIs in post-traumatic stress disorder: an update with recommendations. Drugs. 2004;64:383-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi UK. [The effect of bilateral eye movements, imaginal exposure, and imagery rescripting on intrusive memory: an experimental study]. Cogn Behav Ther Korea. 2014;14:165-190. |

| 9. | Choi UK. Effects of prolonged exposure for PTSD: A pilot study. Cogn Behav Ther Korea. 2010;10:97-116. |

| 10. | Beck JG, Palyo SA, Winer EH, Schwagler BE, Ang EJ. Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for PTSD symptoms after a road accident: an uncontrolled case series. Behav Ther. 2007;38:39-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Meyerbröker K, Emmelkamp PM. Virtual reality exposure therapy in anxiety disorders: a systematic review of process-and-outcome studies. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:933-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee J. Comparisons of Middle- and Old-Aged Drivers’ Recognition for Driving Scene Elements using Sensitivity, Response Bias, and Response Time. Korean Data Anal Soc. 2018;20:3185-3199. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Marmeleira J, Ferreira I, Melo F, Godinho M. Associations of physical activity with driving-related cognitive abilities in older drivers: an exploratory study. Percept Mot Skills. 2012;115:521-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Global Industry Analysts. Market research reports, 2022. |

| 15. | Chae JH, Kim HJ. [Prolonged exposure for post-traumatic stress disorder: A case report]. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;5:1-10. |

| 16. | Park JW, Oh SH. [A study on the development of VR-based life care contents for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for traffic accident]. J Korean Inst Next Gener Comput. 2013;14:56-65. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/