Published online Sep 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.108429

Revised: April 27, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: September 6, 2025

Processing time: 84 Days and 3.4 Hours

Meningiomas represent the most common primary intracranial tumor in adults. The majority of meningiomas are indolent, benign, and sporadic in nature. The incidence of meningiomas is directly proportional to the age, peaking around 65 years. The presenting symptomatology of intracranial meningiomas is mainly dependent on their anatomical location, as with the majority of brain tumors. Surgical resection and radiation therapy remain the treatment modality for meningiomas of all grades.

We present a case describing a 78-year-old female who came in following a ground level fall. The primary assessment was notable for a history of similar recurrent falls and subtle left-sided peripheral visual field loss. Further neuro

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for intracranial pathology in elderly patients with nonspecific presentation.

Core Tip: This case report presents an unusual clinical scenario describing a 78-year-old female who was admitted after a ground-level fall. Neuroimaging unexpectedly revealed a large intracranial mass, measuring over 6 cm at its greatest and situated in the posterior falx. It was associated with extensive vasogenic edema and mass effect. This imaging finding was remarkable given the minimal symptomology of the patient's presentation with no significant neurological deficits. Only a subtotal resection was feasible in our case. Histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of fibrous meningioma with areas of focal necrosis. Other info: (1) Informed consent was obtained; (2) Does not apply to case reports; (3) Manuscript has been reviewed multiple times; and (4) Fibrinous meningioma represents a rare and under-characterized histological variant ofmeningioma, with distinct pathological features such as extensive fibrin deposition and reduced tumor cellularity. This case does not exemplify a new treatment or new mechanism research. The case has an educational value regarding rare occurrence of subtype of meningiomas.

- Citation: AlSabea N, Syeda S, Gubran M, Gibatova V, Sharma R, Aswani A. Atypical presentation of a large posterior falx meningioma involving the parafalcine region in a 78-year-female: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(25): 108429

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i25/108429.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.108429

Meningiomas are dural-based tumors originating from either arachnoid cap or meningothelial cells[1]. They represent the most common primary intracranial tumor in adults. The majority of meningiomas are indolent, benign, and sporadic in nature. These tumors account for approximately 41.7% of all tumors and 56.8% of all non-malignant tumors[2]. The incidence of meningiomas is directly proportional to the age, peaking around 65 years. Additionally, they are twice as prevalent in females compared to males, with a threefold increase observed between the ages of 35 to 54 years. Subtypes of meningiomas classified by histology include meningothelial, fibrinous, psammomatous, angiomatous, microcystic, secretory, lymphoplasmacytic-rich, metaplastic, choroid, clear cell, papillary and rhabdoid which are further classified into World Health Organization (WHO) grade I (benign), II (atypical) and III (malignant)[3].

Benign brain tumors demonstrate a favorable prognosis with an estimated five-year relative survival rate of around 92.0%[2]. Among the histological subtypes, fibroblastic (fibrinous) meningiomas represent approximately 7%-11% of all meningiomas, with only 8% of those arising in the posterior fossa or parafalcine area[3]. Fibrinous meningiomas are characterized microscopically by spindle-shaped meningothelial cells arranged in interlacing fascicles, accompanied by abundant collagen production and a dense reticulin network. These tumors are typically slow-growing and benign, with a favorable prognosis following complete surgical resection. The presence of excess fibrin or a proteinaceous matrix may occasionally be seen secondary to prior hemorrhage, infarction, or inflammatory response within or adjacent to the tumor.

The presenting symptomatology of intracranial meningiomas is mainly dependent on their anatomical location, as with the majority of brain tumors[1]. Those arising specifically in the posterior fossa or falx cerebri may exhibit bulbar palsy, cerebellar symptoms, paresis, facial palsy, hearing deficit, lower cranial nerve palsies, and neck pain.

Therefore, the overall presentation is contingent on the exact tumor location and its degree of local invasion. Cases of high-grade meningiomas, exhibiting a mass effect with surrounding edema, produce more pronounced neurological symptoms. However, in patients who are minimally symptomatic, identification and robust early differential is challenging. Therefore, we describe a case of a patient with large posterior falx meningioma involving the parafalcine region, exhibiting significant mass effect but presenting with lack of expected clinical manifestations.

This is a 78 year old Black female who presented to our emergency department after experiencing a fall at her home. Patient tried reaching for her phone, lost her balance and fell backwards hitting the back of her head but not losing consciousness. She was on the floor, unable to get up for 20-24 hours until found by her neighbors.

The patient reported having numbness in her bilateral upper extremities and occasional loss of balance due to her arthritis and older age. She also confirmed that she has a left-sided visual field deficit. Otherwise, she denied any headaches, weakness, fatigue, weight loss, loss of consciousness or seizure activity. She reports knowing the mass findings for a few years but does not recall its progression. Her last computed tomography (CT) head reported on 7/7/23 prior to hospital admission showed posterior parafalcine extra axial mass measures grossly 2.8 cm × 3.8 cm × 3.6 cm, no significant vasogenic edema. At the time, the patient's PCP recommended no further investigation of the mass.

The patient reported having a history of hypertension and arthritis. There were no surgeries or procedures related to the central nervous system (CNS) system. She has a remote history of hysterectomy.

No personal and/or family history reported by patient.

In the ED, the patient was not in any acute distress. Vital signs were within normal range: Blood pressure, 122/85, Temperature 36.9°C, heart rate 84 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air.

Physical examinations was within normal limits.

She had elevated levels of creatine kinase, 1856, all other values within normal ranges.

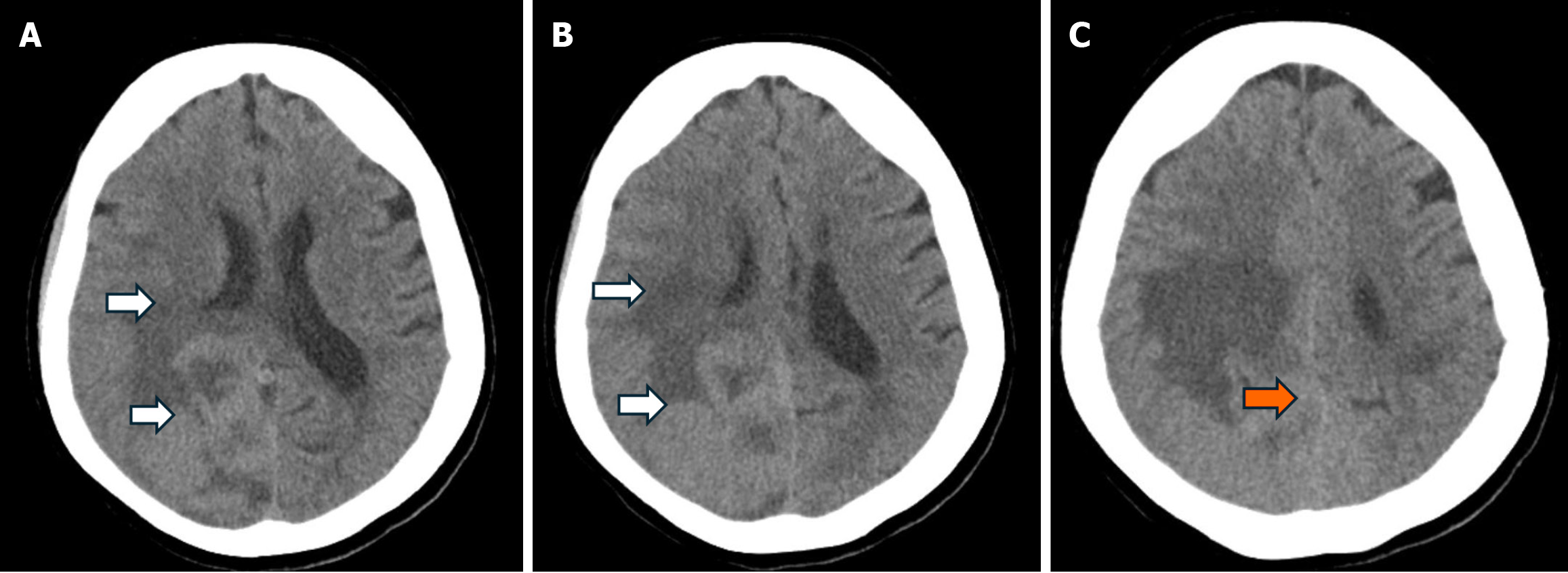

CT cervical spine, chest, pelvic and knee X-rays were unremarkable. CT head without contrast (Figure 1) showed a moderately large area of vasogenic edema (white arrows, Figure 1) seen in the posterior right parietal lobe extending into the right temporal and occipital lobe. There is also mild deviation of the posterior falx as seen with the orange arrow in Figure 1. In this non-contrast study, there is a suggestion of a probable mass lesion along the posterior parietal region crossing the midline measuring at least 3.8 cm × 6.1 cm × 7.2 cm. Findings suggest a probable extra-axial mass lesion though full characterization cannot be performed. Neurosurgery was consulted and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered. Due to the vasogenic edema, neurosurgery added IV Dexamethasone 10 mg loading dose followed by dexamethasone 6 mg every 6 hours maintenance dose.

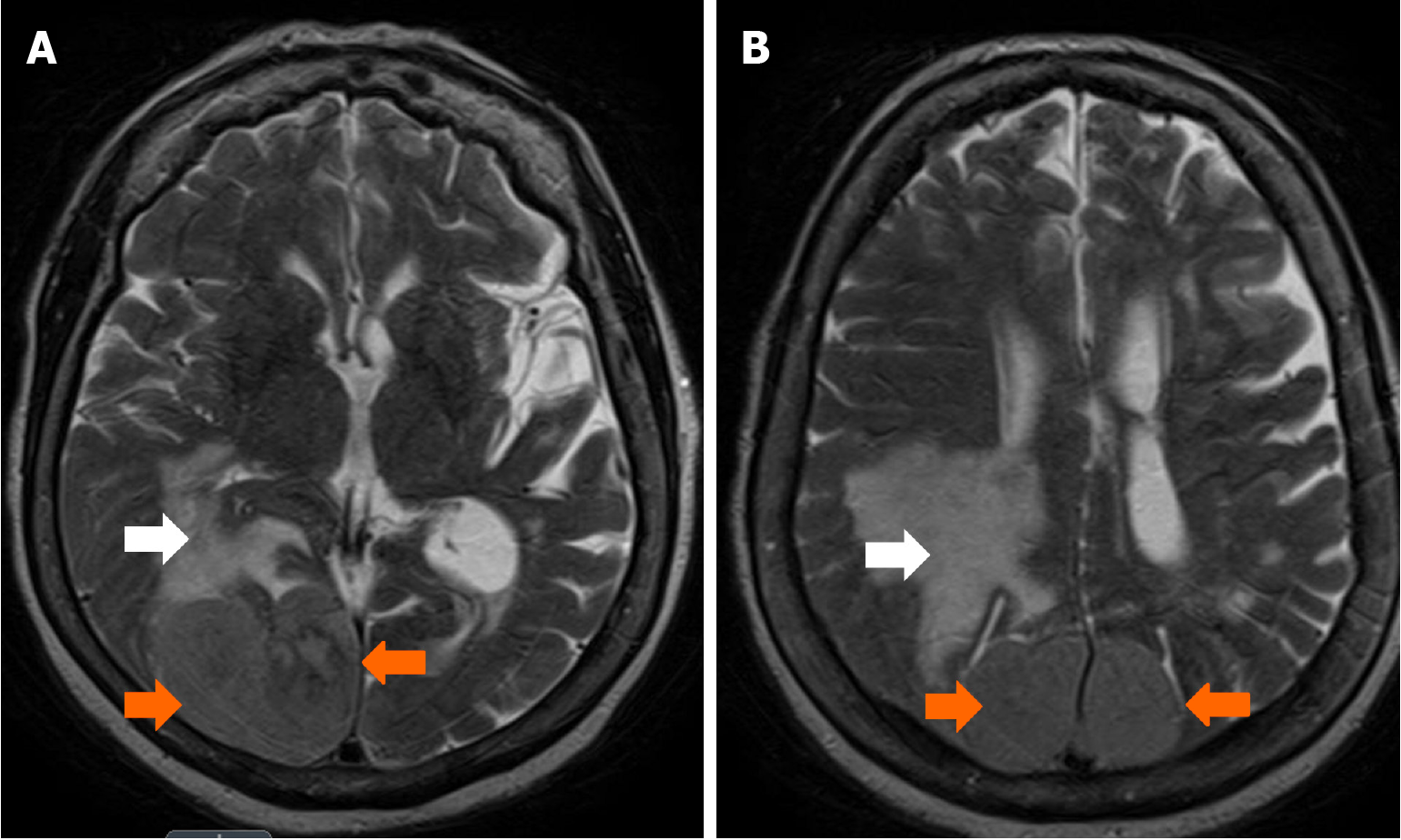

On her 2nd day of admission, MRI head w/wo contrast (Figure 2) showed a large 6.6 cm extra-axial, enhancing mass along the posterior aspect of falx bilaterally (orange arrows, Figure 2) which results in prominent mass effect with sulcal effacement and partial effacement of the right lateral ventricle. The mass surrounds the superior sagittal sinus and partially compresses but does not occlude the sinus. There is prominent edema involving the right cerebrum, most predominantly the right parietal and occipital lobes. Neurosurgery recommended a craniotomy for tumor resection. Patient consented to the craniotomy for the following day, she was kept nil per os (NPO, nothing by mouth) and her steroid regimen was continued.

Neurosurgery: Recommended emergent neurosurgical intervention.

Fibrous meningioma.

Using microdissection techniques, a plane on the inferior and lateral aspect of the tumor was established followed by sequential debulking. The tumor was subsequently elevated from the underlying occipital cortex and truncated from the falx. Using the stereotactic navigation system, the falx was coagulated and resected from the inferior sagittal sinus. This approach facilitated exposure of the contralateral meningioma located on the left side; however, resection was deferred due to suboptimal visualization and concerns regarding hemostatic control in the operative field, which posed a significant risk of intraoperative complications. After tumor resection, significant decompression of the brain was achieved with excellent post-surgical hemostasis. The tissue was subsequently sent for pathological analysis.

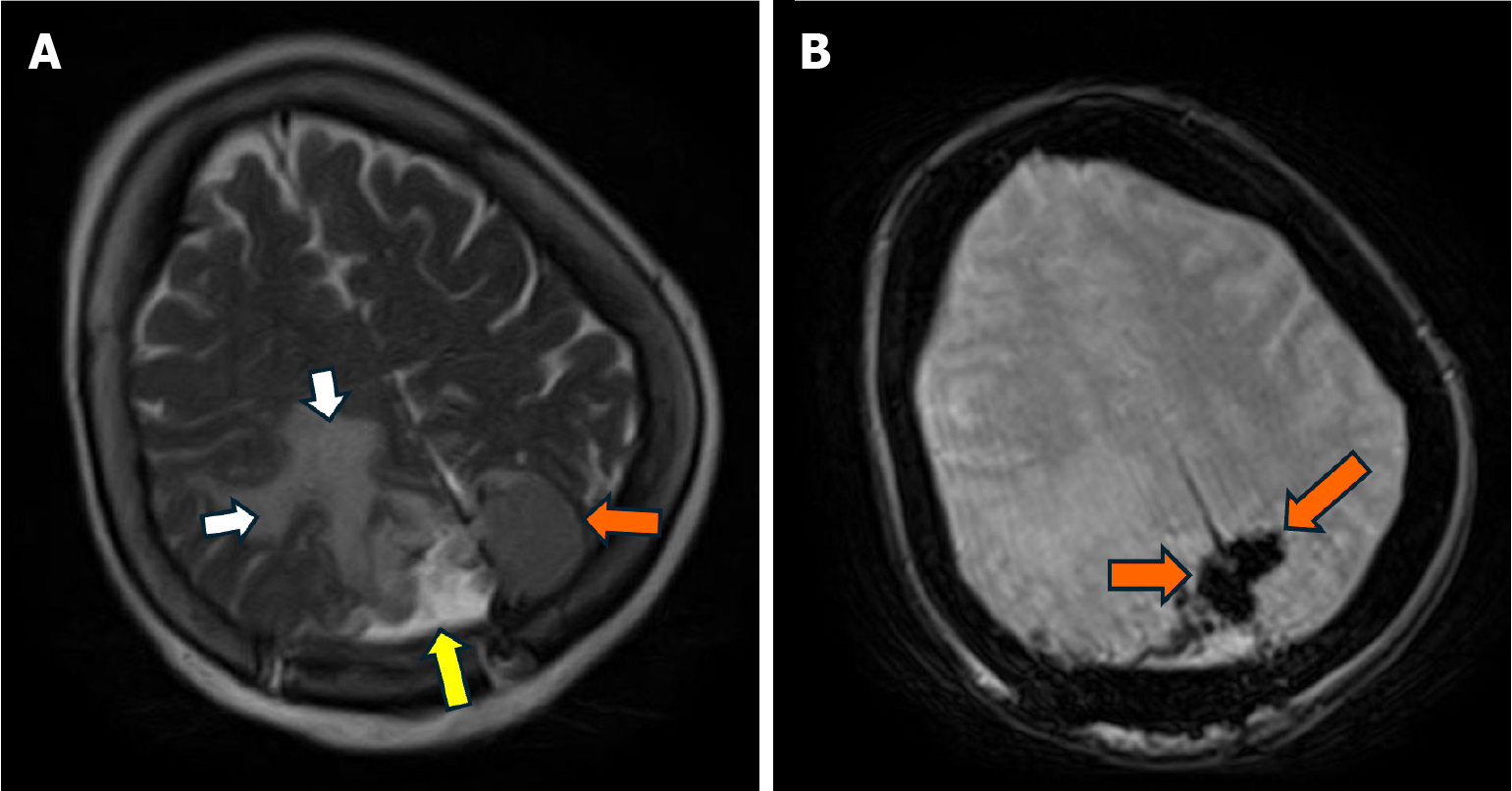

Pathology of the brain specimen confirmed fibrous meningioma with focal necrosis, WHO grade 2. A postoperative MRI brain (Figure 3) showed status post resection with some residual tumor remaining in the left and right posterior parietal parafalcine region with measurements as above. Some associated postoperative blood products (yellow arrow, Figure 3) and decreased vasogenic edema (white arrows, Figure 3) and decreased mass effect on the posterior horn of the right lateral ventricle.

Most meningiomas present with headaches, seizures, hearing loss, vision loss or double vision, memory issues and/or weight loss. This patient’s presentation was atypical in that her only symptoms were vague left-sided vision loss and bilateral upper extremity numbness. Even her loss of balance was from an unknown cause. Her past medical history of arthritis could also contribute to her presentation. The patient’s visual symptoms were mostly related to the right side part of her fibrinous meningioma situated between the occipital and parietal lobes. Hence why the neurosurgeons decided to resect the right side of the meningioma and leave the left side intact. Other than suboptimal visualization and concerns regarding hemostatic control, the left-sided meningioma was asymptomatic.

Patient stayed in surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for 3 days following her craniotomy due to the need for Hemovac drain. When she first regained her consciousness, she was alert to person and place only. She was slightly confused and pulled her IVs out hence, was softly restrained. Her only complaint was light sensitivity. The patient reported her left-sided vision was slowly coming back and the numbness in her bilateral upper extremities was fading. During the first week after surgery and on the medical floor, physical therapy/occupational therapy evaluation indicated that the patient needs post-acute rehab facility upon discharge. Neurosurgery recommended weaning the patient off dexamethasone over the next 8 days and starting Keppra 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

Patient tolerated the surgery well and reported improving left-sided vision after surgery. She was discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility based on Karnofsky Performance score of 50 points, ECOG Performance Status of 2 and Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living (ADL) score of 45 (partially independent). Patient was recommended to follow-up with radiation oncology in 3 months to assess the growth of left-sided meningioma and the need for radiation vs resection. At the time of writing this case, the patient has still not followed up with radiation oncology to determine if she will resect the left-sided meningioma or get radiation therapy.

Epidemiologically, meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial tumors, accounting for approximately 30%-35% of all CNS tumors[4]. They originate in the protective covering of the brain known as the meninges from the meningothelial arachnoid cap cells. They have a higher incidence in females, with a female-to-male ratio of about 2:1, particularly in WHO grade I variants[4]. Majority of meningiomas are diagnosed in middle-aged to elderly individuals, with a peak incidence between the ages of 40 and 70 years[4].

Fibrinous meningioma is a rare histopathological variant of meningioma characterized by extensive fibrin deposition within the tumor stroma. This distinct morphological feature differentiates it from other subtypes of meningiomas and poses challenges in diagnosis and classification. The underlying mechanisms contributing to the excessive fibrin accumulation remain unclear, though some studies suggest an association with increased vascular permeability and tumor microenvironment alterations[5,6]. While fibrinous meningiomas are exceedingly rare, their precise incidence remains undetermined due to limited case reports and studies[7]. The contribution of fibrinous meningioma to overall meni

Clinically, the presentation of fibrinous meningioma does not appear to differ significantly from other meningioma subtypes. Patients often present with symptoms related to mass effect, including headaches, seizures, and focal neurological deficits[4]. However, the impact of fibrin deposition on tumor behavior, recurrence rates, and prognosis remains poorly understood. Some authors hypothesize that the presence of extensive fibrin may correlate with altered tumor vascularity, potentially influencing response to therapy and recurrence patterns[6,7].

Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for fibrinous meningiomas, similar to other meningioma variants. Gross total resection is typically pursued when feasible, with adjuvant radiotherapy considered for higher-grade lesions or subtotal resections[8]. The role of fibrinous composition in influencing surgical outcomes warrants further investigation, as excessive fibrin deposition could theoretically impact tumor consistency and resectability.

In the present case, the tumor was approached using stereotactic navigation and microdissection techniques, which allowed for safe debulking and removal from the occipital cortex. The falx was coagulated and partially resected to expose a contralateral lesion, which was not resected due to visualization limitations and bleeding risk. The asymp

Due to limited information on causes of fibrin accumulation, future research should aim to elucidate the molecular pathways driving fibrin accumulation in meningiomas, as well as its prognostic significance. Further studies with larger patient cohorts and long-term follow-up are essential to better characterize the biological behavior of this rare meningioma subtype. The atypical patient presentation, that is mild symptoms despite the large tumor size also needs to be further investigated. Additionally, investigating potential therapeutic targets within the fibrin deposition pathway may offer novel strategies for managing these tumors more effectively.

Fibrinous meningioma represents a rare and under-characterized histological variant of meningioma, with distinct pathological features such as extensive fibrin deposition and reduced tumor cellularity. Although clinical presentation aligns with more common meningioma subtypes, its true epidemiological prevalence, impact on prognosis, and influence on treatment outcomes remain poorly defined. Moreover, the threshold for initiating early diagnostic evaluation in elderly patients presenting with subtle or nonspecific symptoms should remain low. Even minimal clinical suspicion should prompt timely imaging studies, given the atypical and often muted presentations, which can obscure early detection and delay critical intervention. Accurate diagnosis relies on careful histological and immunohistochemical assessment. Given the potential implications of fibrin accumulation on tumor biology and resectability, further research is essential to clarify its clinical significance and explore targeted therapeutic strategies.

A key limitation of our case report, consistent with inherent constraints of single-case analyses, lies in the limited generalizability due to the atypical presentation observed. Nevertheless, the case highlights the profound clinical impact that heightened early recognition can have on patient outcomes, emphasizing its considerable relevance to practice.

Thanks for all the treatment team and the authors to help taking care of the patient.

| 1. | Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14:2161-2177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Price M, Ballard C, Benedetti J, Neff C, Cioffi G, Waite KA, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Ostrom QT. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2017-2021. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26:vi1-vi85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 109.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bhat AR, Wani MA, Kirmani AR, Ramzan AU. Histological-subtypes and anatomical location correlated in meningeal brain tumors (meningiomas). J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G, Waite KA, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015-2019. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24:v1-v95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 1013] [Article Influence: 253.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10993] [Cited by in RCA: 11218] [Article Influence: 1121.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brat DJ, Scheithauer BW, Fuller GN, Tihan T. Newly codified glial neoplasms of the 2007 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System: angiocentric glioma, pilomyxoid astrocytoma and pituicytoma. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carneiro SS, Scheithauer BW, Nascimento AG, Hirose T, Davis DH. Solitary fibrous tumor of the meninges: a lesion distinct from fibrous meningioma. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Backer-Grøndahl T, Moen BH, Torp SH. The histopathological spectrum of human meningiomas. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:231-242. [PubMed] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/