Published online Sep 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.108124

Revised: April 26, 2025

Accepted: May 27, 2025

Published online: September 6, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 1.6 Hours

Patients with schizophrenia may lack awareness of the importance of post-tracheotomy care due to the impact of their condition, often showing resistance or misunderstanding of care measures. When coupled with the impact of negative symptoms and the risk of complications after tracheotomy, patients may experience emotional fluctuations, restlessness, anxiety, and hostile behaviors, which pose significant challenges to nursing work.

We have reported the case of an 87-year-old male patient who was admitted to the hospital because of negative symptoms of schizophrenia and who underwent tracheotomy for severe pneumonia. In this study, we have summarized the nursing experience of a patient with negative symptoms of schizophrenia who underwent tracheotomy. The key nursing strategies included proper tracheotomy care, the management of psychiatric symptoms, a thorough assessment and implementation of enteral and parenteral nutrition, effective skincare, infection prevention, and comprehensive mental care. Individualized nursing skills helped stabilize the patient’s condition, followed by isolation and observation in a psychiatric hospital.

Effective postoperative tracheostomy care in patients with schizophrenia necessitates a tailored, multidisciplinary approach that addresses their psychiatric, physical, and emotional needs to achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

Core Tip: Managing postoperative tracheostomy care in elderly patients with chronic schizophrenia, particularly those presenting with negative symptoms and multiple comorbidities, presents significant clinical challenges. This case report discusses an 87-year-old man with a 63-year history of schizophrenia, complicated by pneumonia and other health issues, who exhibited persistent low mood and restlessness after undergoing a tracheostomy. We present novel clinical strategies and practical care approaches designed to support nursing staff in psychiatric settings. The involvement of a multidisciplinary care team and comprehensive risk assessments are essential for enhancing patient outcomes and experiences in similar complex cases. This report underscores the importance of specialized, integrative care in managing postoperative recovery in older adults with long-standing schizophrenia.

- Citation: Li JY, Liu XE, Li W, Wang LN. Nursing care of a patient with negative symptoms of schizophrenia who underwent tracheotomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(25): 108124

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i25/108124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.108124

Schizophrenia usually manifests as a chronic and disabling disorder characterized by heterogeneous positive and negative symptom constellations[1]. The disease course is often prolonged, demonstrating repeated attacks or deterioration, with the possibility of decline. The presentation of the following five characteristic symptoms or at least two of them being present for a month are required for the diagnosis of schizophrenia DSM-5: Delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms; it is also required that at least one of the minimum two requisite characteristic symptoms be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech[2]. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as anhedonia, affective blunting, and social withdrawal, which often appear earlier than any other symptoms, are prominent and clinically relevant in the majority of these patients[3]. These symptoms substantially account for the impairment of health, social functioning, and quality of life, and their treatment is often difficult[4]. Patients with mental illnesses along with severe pneumonia are more likely to experience increased anxiety, anger, impulsiveness, and strong suicidal thoughts[5]. Meanwhile, the negative effects of invasive mechanical ventilation through a tracheotomy may impair mental health, such as worries and insecurity. There have been limited studies on nursing care for patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia undergoing tracheotomy and inadequate nursing experience reports. We have summarized here the nursing experience of an elderly patient with negative symptoms of schizophrenia who underwent a tracheotomy due to severe pneumonia in March 2023.

An 87-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital in March 2023 with a 63-year history of schizophrenia characterized by negative symptoms. He had undergone a tracheotomy 86 days earlier due to severe pneumonia.

The patient has displayed behavioral symptoms such as social withdrawal, laziness, and an inability to communicate effectively for the past 63 years. A workplace injury in 1960 resulted in social withdrawal and diminished interaction with others. Although he continued his normal daily activities, he experienced the first onset of mental disorders in 1987. He displayed various symptoms such as often being in a daze, social withdrawal, staying indoors, sleep-pattern changes, random self-talk, and algophobia; and his strange behavior gradually worsened. In June 1996, due to hallucinations and delusions of victimization, the patient was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for the first time. After observing symptoms like uncontrolled laughter, confusion, and a lack of self-care, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. In December 2022, the patient was admitted to a general hospital due to fever, excessive coughing, and dyspnea, and underwent a tracheotomy there. The patient was transferred to our hospital for further treatment after his respiratory symptoms had partially improved (Figure 1A). Following his admission, the patient displayed hazy consciousness, lethargy, and intermittent restlessness.

The patient's medical history included hypertension, sinus bradycardia, and pneumonia.

There was no significant family history of psychiatric or medical illness.

On admission, the patient's vital signs were as follows: Temperature, 36.2°C; pulse, 60 beats/min; respiratory rate, 19 breaths/min; blood pressure, 127/67 mmHg; and oxygen saturation, 100%. Auscultation revealed moist rales in both lungs.

nitial laboratory tests showed elevated white blood cell count at 13.75 × 109/L and neutrophil count at 8.79 × 109/L. Blood biochemistry revealed serum calcium and magnesium levels of 2.0 and 0.6 mmol/L, respectively, and a total protein level of 54.9 g/L. Inflammatory markers were elevated, with a C-reactive protein level of 14.14 mg/L and interleukin-6 level of 17.3 pg/mL.

Chest computed tomography revealed bilateral pneumonia and bronchiectasis in the upper lobe of the right lung.

The patient was diagnosed with schizophrenia, severe pneumonia, hypoalbuminemia, and electrolyte imbalance. The nursing diagnosis for our patient was impaired verbal communication, malnutrition, anxiety and fear, risks of infection, asphyxia, skin damage, and unplanned extubation.

The patient was administered first-rate care, including mental nursing care, tracheotomy care, high-flow oxygen therapy with heating and humidification, sputum aspiration, anti-infection, electrocardiogram monitoring, sedation, nutritional support, and other symptomatic treatments.

The patient was conscious, responsive, emotionally stable, and less anxious after > 1 month of personalized treatment and care (Figure 1B), and he would occasionally smile at the nursing staff. His vital signs were stable, and his respiratory function, swallowing reflex, coughing ability, nutritional status, and disease symptoms were gradually improving. Moreover, he had no pressure sores and could defecate daily. Considering the patient's advanced age and multiple comorbidities, the prognosis was deemed poor.

Environment and posture management: We maintained strict hygiene in the ward environment and ensured fresh air supply by ventilating twice a day for 30 min each time. The ward’s temperature and humidity were set at 18°C-22°C and 50%-60%, respectively. Single-room accommodations were arranged to prevent cross-infection and minimize disturbances caused by inappropriate behavior from other psychiatric patients. The patient’s head of bed was raised by 30°-45° to improve lung ventilation and increase the body’s oxygen supply. After nebulization, chest and back percussion were performed while the patient was placed in a seated position so as to promote effective coughing and local blood circulation, thereby enhancing lung function and shortening the duration of the tracheostomy tube placement. Moreover, after turning the patient, the head, neck, and trunk were all kept on the same axis to prevent the cannula’s rotation angle from being too large[6].

Airway management: Patients with sticky sputum were treated by providing heated, humidified high-flow oxygen flow, keeping the airway moist, and atomization for effective sputum discharge and no sputum scab formation that could cause airway blockage and affect breathing. The nursing measures included: (1) To treat phlegm, ambroxol hydrochloride (30 mg) tid was administered orally, and budesonide (1 mg) q8h along with acetylcysteine solution (3 mL) q8h inhalation suspensions were atomized; (2) Daily mechanical expectoration helped in sputum discharge; (3) The sputum aspirator was used to aspirate the sputum with the least negative pressure. In addition, the sputum was aspirated gently to avoid any airway damage. The individual sputum aspiration time was not > 15 s to reduce irritation and the risk of hypoxia for the patient. The frequency of suctioning was usually determined by the patient’s condition and the amount of secretions. Caregivers regularly assessed the patient’s respiratory status and the condition of the secretions to decide if suctioning was needed and how often. In case of oxygen-saturation reduction or difficulty in breathing, the procedure was stopped immediately, and high-flow oxygen inhalation was administered; and (4) The tracheal cuff pressure was maintained at 25–30 cmH2O and measured every 4 h considering that extremely high tracheal cuff pressure might hinder the mucous membrane’s blood flow by adding the pressure of the mucosal lymphatic vessels. Subsequently, the mucous membrane became necrotic, fell off, or got perforated.

Due to a lack of self-awareness and unpredictable behavior of the patient, we ensured that the nurses paid attention to the patient’s dynamics with a focused 24-h monitoring, and kept them separate from other mental illness patients. When administering psychotropic drugs to elderly patients, the efficacy and adverse reactions should be closely monitored, and the dosage should be adjusted accordingly. We should communicate with the patients in a gentle tone, understand their nonverbal movements, show patience, and avoid discussing their illnesses in front of them to avoid anxiety. In our case, when the patient exhibited impulsive behavior that necessitated the use of physical restraint, the following factors were considered: (1) Restriction of the patient’s body position to be comfortable, maintaining the limb’s functional position, and no overstretching of the limbs to avoid sprains or fractures due to osteoporosis; (2) The tightness of the restraint belt was kept appropriate to be able to reach into one finger, and the local skin and blood circulation were observed during the restraint; (3) When the shoulder was restrained, cotton pads were used for underarm cushioning; (4) Restraint mittens were used to avoid unintentional extubation; (5) After turning the patient, the back was patted every 2 h from bottom to top and from outside to inside. The hands were kept spoon-shaped to increase the resonance force when patting; (6) Psychiatrists and nurses were obliged to complete a medical review no later than 4 hours during the day and no later than 12 hours at night after the commencement of physical restraint, and they were required to remove its use unless the risk was sustained[7]; and (7) Medical personnel were not allowed to adopt physical restraint for convenience or to use it as a form of punishment toward the patient who disrupted the therapeutic environment[8].

The present patient’s body composition analysis revealed reduced body weight and muscle fat composition, uneven body water distribution, and swollen trunk and lower limbs. The patient’s segmental phase angle was 2.5, indicating that his poor body condition may become potentially life-threatening. The nursing’s main goal was to increase nutritional intake and prevent aspiration, for which the following measures were taken: (1) The nutritional intake was ensured by feeding the enteral nutrition suspensions and nutritional emulsions regularly; (2) The gastric contents were determined before each nasal feeding, and the patient was fed at a longer interval if it was > 100 mL to avoid gastric retention; (3) An enteral nutrient solution was heated to 38-40°C before nasal feeding and was consumed within 24 h; (4) The nurses avoided twisting, folding, and blocking the nasal feeding tube, and the gastric tube was rinsed with warm water after feeding. Aspiration was avoided by elevating the head of the bed at the time of feeding by the nose or by the mouth. First, the gastric tube’s position in the stomach was determined using an adhesive tape to secure the gastric tube in place to prevent it from moving. Second, normal airbag pressure was maintained, considering that insufficient airbag pressure may lead to aspiration after descent into the lungs, and the residues and secretions on the airbag were cleaned promptly; and (5) Drugs were used to promote gastric motility, as directed by the doctor. In a stable condition, drugs can be given orally to restore gastrointestinal motility, and feeding should be stopped in case of coughing.

Pressure injuries develop due to long-term bed rest, incontinence, a long-term indwelling gastric tube, and a tracheotomy cannula, among others. However, the patient’s skin remained intact with no pressure injuries, thanks to the meticulous care provided by the nursing staff. The nursing measures included the following: (1) The indwelling gastric tube is made of soft material and was replaced regularly to avoid nasopharyngeal discomfort and skin ulcers; (2) The tightness of the tracheotomy cannula fixation band was kept appropriate. The neck skin was wiped with normal saline after removing the old fixing belt to clean it. Furthermore, the gauze was wrapped around the fixing belt during the dressing change after the tracheotomy to prevent neck redness and ulceration of the neck skin; (3) An air cushion bed was used to avoid pressure injuries, and a pressure relief pad or protective device was applied to the area of the bone bulge so as to reduce local pressure. For example, irrigated rubber gloves were used under areas such as the elbows and heels; and (4) The patient’s vomit, excrement, wet clothes, and sheets were kept clean at all times, and the skin was cleaned with warm water to make it clean and sweat-free.

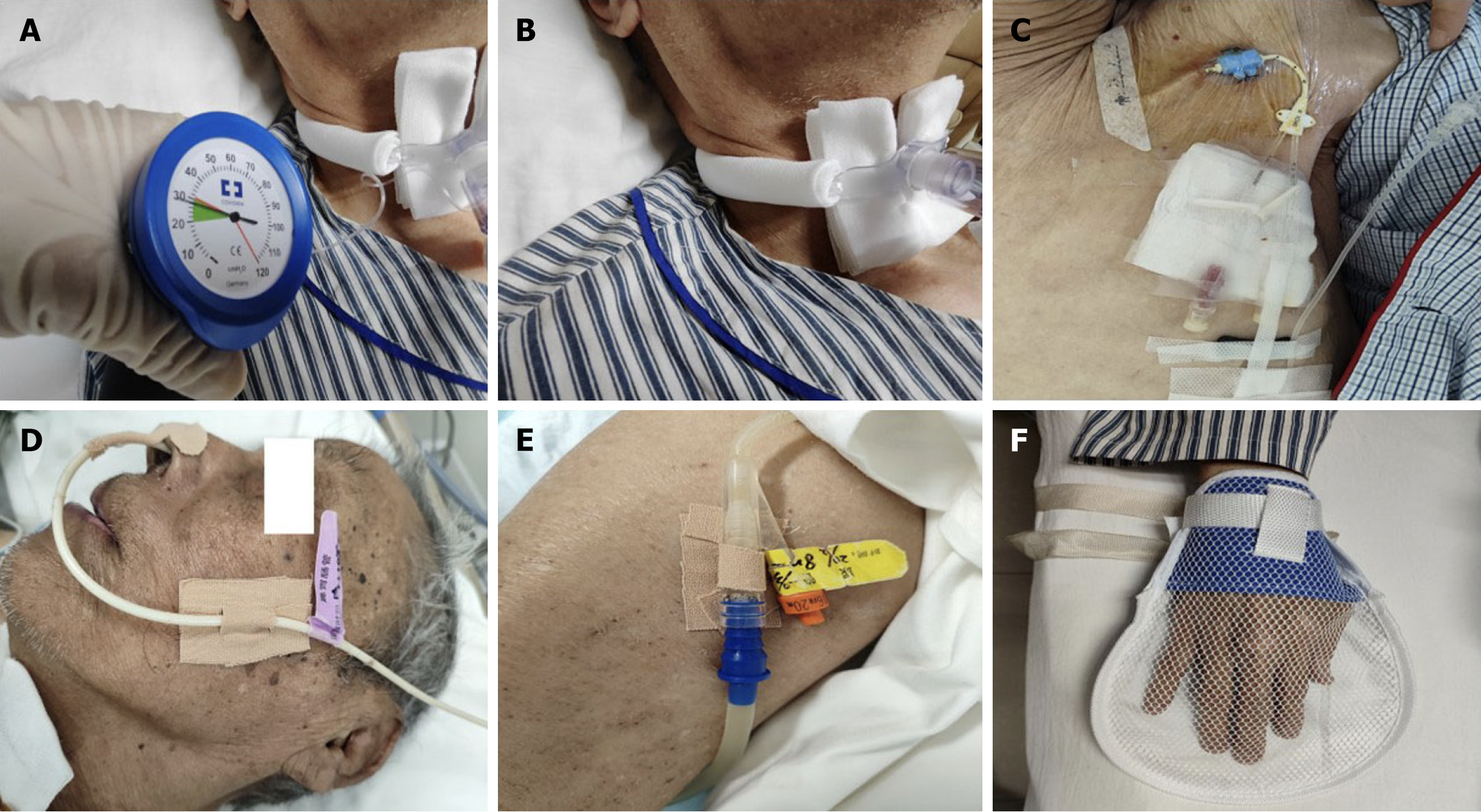

All tracheal cannulas, central venous catheters, gastric tubes, and other devices were reserved. Based on the patient’s mental status, cognitive function, and the degree of treatment compliance, comprehensive and continuous assessments of the likelihood of unplanned extubation were conducted. Regular monitoring and adjustment of the tracheal cuff pressure are essential for maintaining the correct position of the tracheostomy cannula and minimizing its movement within the trachea (Figure 2A). Proper fixation of medical devices—including the tracheostomy tube (Figure 2B), central venous catheter (Figure 2C), gastric tube (Figure 2D), and urinary catheter (Figure 2E)—is critical to prevent accidental dislodgement. By providing the necessary information about the tubing to the caregivers, including its function, purpose, and potential risks, it was ensured that the caregivers also understood its necessity and were attentive to the patient’s safety. Using distraction strategies, such as playing music that the patient enjoys, can reduce the patient’s focus on the tubing, which lowers the likelihood of extubation. In addition, behavioral interventions such as the application of gentle restraints, including restraint gloves (Figure 2F), can significantly reduce the risk of unplanned extubation. If necessary, a psychiatrist could be consulted for medication management and physical constraints. In addition, nursing staff should strengthen monitoring and patrol practices and take shift handovers seriously. Moreover, the doctor should be notified immediately in case of any unplanned extubation and first aid should be applied as soon as possible.

The infection risk was increased greatly as the patient was bedridden for a longer time, had poor nutritional status, and had a tracheotomy along with central venous and urinary catheters in place for an extended period. The nursing care included the following steps: (1) Oral care was performed daily to keep the oral cavity clean, moist, and odorless as well as to prevent bacterial respiratory tract infections; (2) The tracheotomy wound skin was closely monitored, and an aseptic dressing was applied daily to keep the skin clean and dry. However, the dressing was changed as soon as there was an exudate, bleeding, secretion, or sputum discharge. Physical therapy or topical drugs were considered in cases of reddish skin development around the incision; (3) All aseptic procedures were followed during sputum aspiration, and the sputum aspiration tube that had already been pulled up was not reinserted downward. If the sputum aspiration was incomplete, it was replaced with a new sputum aspiration tube for respiration. Furthermore, the sputum aspiration tube was never inserted up and down to avoid any infections; (4) A vein catheterization maintenance was performed by proper catheter fixation and flushing daily to keep it clear and the dressing was changed regularly to prevent infection; and (5) As suggested by previous studies, we focused on reducing the length of stay and urinary catheter device utilization ratio to avoid urinary catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and implemented evidence-based CAUTI prevention recommendations[9].

The patient was in extremely critical condition and faced a death threat. The use of various instruments after tracheotomy had increased the patient’s anxiety and fear. In addition, due to two instances of unplanned extubation, the use of physical restraints intensified the patient’s emotional responses, which led to the development of symptoms of depression, anger, and helplessness, further exacerbating his mental health symptoms. The following steps were taken in this situation: (1) The nurses “empathized” with the patients’ feelings of loneliness and cared for them; (2) When the patient was unable to speak and was called by name, the nurses responded by touching him, giving him the impression that he was cared for; (3) All procedures were performed gently, and close attention was paid to the protection of private parts so that the patient did not feel any disrespect; (4) In the convalescence stage, the patient could cooperate with doctors to improve his psychological rehabilitation ability through supportive psychotherapy and cognitive therapy; and (5) The support of the family also affects the patient’s mental health, hence we encouraged the patient to use electronic devices to chat with family. Furthermore, the family members’ supportive attitudes were evaluated, and we worked with the families to provide consistent psychological care to the patient.

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects the social function and quality of life of patients. In the case of our patient, three major challenges were encountered in the early stage of nursing. First, communication between the nurse and patient was difficult; the patient had been suffering from schizophrenia for 63 years, lacked self-awareness, and had evident negative symptoms, which made it difficult to accurately grasp the patient’s condition and needs and to accordingly adopt the targeted nursing care. Second, knowledgeable multidisciplinary staff were required to handle the patient’s care regimen. The patient was 87 years old and had multiple serious physical illnesses, which warranted a high level of nursing expertise. Third, the treatment cooperation was poor. After undergoing tracheotomy, the patient displayed low mood, fear, and sometimes restlessness, he repeatedly attempted to remove the tracheal cannula and other tubes but was promptly stopped. The patient showed significant risks of malnutrition, unplanned extubation, infection, pressure ulcers, and other symptoms. The condition of the patient was complex and rare, and improper care could have led to a series of problems, some even life-threatening. At present, there is no report on the nursing care of patients with negative symptoms of schizophrenia who underwent tracheotomy, which is a complex condition. Therefore, we have summarized the entire process from the time of hospital admission to the stabilization of the patient’s condition in the hope of providing others with a reference in nursing care.

Comforting and improving the patient psychologically for recovery were important aspects to be considered in our care journey. We communicated fully with the patient to relieve his psychological negative emotions and establish confidence in the patient for the treatment. The patient was withdrawn, had poor speech, and could not communicate effectively with clinical nurses. Therefore, we provided targeted and systematic intervention methods through close observation, verbal comfort, nonverbal encouragement, and other measures to ensure that he would show better cooperation with our treatment, and, accordingly, continuously worked toward improving the nursing plan based on patient feedback. The patient gradually responded to the care of nurses and cooperated with the treatment, as well as conveying his needs through his eyes and using simple words, suggesting that the adopted measures were effective.

The complexity of tracheotomy care is dependent on a range of professional expertise, and emerging evidence suggests that optimal tracheotomy management requires a multidisciplinary approach[10]. Care by a multidisciplinary team composed of psychiatrists, nurses, respiratory physiotherapists, speech-language pathologists, dieticians, and psychologists, from a wide range of specialty backgrounds, is beneficial for patients[11].

Schizophrenia patients affected by mental symptoms are prone to attack and destruction of objects, self-injury suicide, and non-cooperation with treatment. To timely control the occurrence and escalation of harmful behaviors, physical restraint has become a mandatory protective measure implemented in psychiatric wards to cope with risks such as suicide, falls, and unplanned extubation. We suggests that restraint should be applied when no other alternative measures are available, using the lowest degree and shortest period of restraint. Our patient was an elderly patient who had been bedridden for a long time with such risks, and the use of physical restraint was applied rarely and cautiously to avoid any adverse effects on the patient’s physical, psychological, and doctor–patient relationships, such as mobility disorders, skin injuries, deep vein thrombosis, constipation, and lack of cooperation with the treatment. It was necessary to build an effective risk-assessment system for such patients, fully considering their multidimensional needs and complex physical conditions, as well as implementing differentiated risk-management strategies.

As cases of negative symptoms of schizophrenia complicated by multiple complications are rare, especially after undergoing tracheotomy, information about post-tracheotomy nursing of such cases is also limited. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a post-tracheotomy nursing experience of negative symptoms of schizophrenia complicated by multiple complications in a psychiatric ward. This report summarizes our nursing experience in the light of relevant literature, which could be useful for guiding post-tracheotomy nursing of this type of patient. We hope that our findings will be helpful for the rehabilitation of such patients. However, considering that our nursing intervention was based on a single case, some measures may not apply to other patients because of individual differences. Therefore, we hope that more clinical nurses can share their nursing experience about similar conditions in the future to help create a better care plan.

We have reported here the nursing experience of an elderly schizophrenic patient who presented with negative symptoms, lack of self-knowledge, and poor compliance. After tracheotomy, the symptoms of viscous sputum, hypoxemia, and hypoproteinemia appeared. Because of the patient’s discomfort and fear of tracheotomy, the risk of unplanned extubation was increased, making it more difficult for the nursing staff to precisely conduct care measures after tracheotomy and suitably manage the patient’s mental symptoms. Meanwhile, the prevention of infection and psychological care were also very important. After > 1 month of careful nursing, the patient’s life indexes became stable, indicating good efficacy of nursing interventions. Our experience indicated that newer clinical coping strategies and effective modalities need to be devised for the nursing staff caring procedures for older schizophrenic patients who have undergone tracheotomy in a psychiatric hospital. This case has important clinical implications for psychiatric nursing practice, as it offers a more scientific and systematic approach to nursing care for patients with schizophrenia exhibiting negative symptoms after tracheotomy. The insights gained can aid in promoting patient rehabilitation and improving overall quality of life. By presenting this case, we aim to enhance caregivers’ understanding of how to deliver safe and effective care in complex clinical scenarios, ultimately advancing the quality and efficacy of psychiatric nursing practice.

We express our sincere gratitude to all the physicians and nurses in the Department of Psychiatry who contributed to the clinical and biochemical data collection, diagnosis, and treatment of this patient.

| 1. | Correll CU, Schooler NR. Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Review and Clinical Guide for Recognition, Assessment, and Treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:519-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 88.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gur RE, Heckers S, Malaspina D, Owen MJ, Schultz S, Tsuang M, Van Os J, Carpenter W. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:3-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Marder SR, Umbricht D. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Newly emerging measurements, pathways, and treatments. Schizophr Res. 2023;258:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wójciak P, Rybakowski J. Clinical picture, pathogenesis and psychometric assessment of negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Pol. 2018;52:185-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, Hu Y, Luo X, Jiang X, McIntyre RS, Tran B, Sun J, Zhang Z, Ho R, Ho C, Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 624] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 111.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Trouillet JL, Collange O, Belafia F, Blot F, Capellier G, Cesareo E, Constantin JM, Demoule A, Diehl JL, Guinot PG, Jegoux F, L'Her E, Luyt CE, Mahjoub Y, Mayaux J, Quintard H, Ravat F, Vergez S, Amour J, Guillot M. Tracheotomy in the intensive care unit: guidelines from a French expert panel. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mental Health Professional Committee of Chinese Nursing Association. Expert consensus on the implementation and removal of protective restraints in psychiatry. Chin J Nurs. 2022;57:146-151. |

| 8. | Ye J, Wang C, Xiao A, Xia Z, Yu L, Lin J, Liao Y, Xu Y, Zhang Y. Physical restraint in mental health nursing: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6:343-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yin R, Jin Z, Lee BH, Alvarez GA, Stagnaro JP, Valderrama-Beltran SL, Gualtero SM, Jiménez-Alvarez LF, Reyes LP, Henao Rodas CM, Gomez K, Alarcon J, Aguilar Moreno LA, Bravo Ojeda JS, Cano Medina YA, Chapeta Parada EG, Zuniga Chavarria MA, Quesada Mora AM, Aguirre-Avalos G, Mijangos-Méndez JC, Sassoe-Gonzalez A, Millán-Castillo CM, Aleman-Bocanegra MC, Echazarreta-Martínez CV, Hernandez-Chena BE, Jarad RMA, Villegas-Mota MI, Montoya-Malváez M, Aguilar-de-Moros D, Castaño-Guerra E, Córdoba J, Castañeda-Sabogal A, Medeiros EA, Fram D, Dueñas L, Carreazo NY, Salgado E, Rosenthal VD. Prospective cohort study of incidence and risk factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infections in 145 intensive care units of 9 Latin American countries: INICC findings. World J Urol. 2023;41:3599-3609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bonvento B, Wallace S, Lynch J, Coe B, McGrath BA. Role of the multidisciplinary team in the care of the tracheostomy patient. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wiberg S, Whitling S, Bergström L. Tracheostomy management by speech-language pathologists in Sweden. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2022;47:146-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |