Published online Sep 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.107948

Revised: April 22, 2025

Accepted: May 18, 2025

Published online: September 6, 2025

Processing time: 97 Days and 13.2 Hours

Bradycardia, renal failure, atrioventricular nodal blockade, shock, and hyper

We present a case of a 54-year-old male on a beta-blocker and angiotensin-con

Increased awareness of BRASH syndrome may improve outcomes through timely diagnosis and aggressive intervention.

Core Tip: Bradycardia, renal failure, atrioventricular nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalemia (BRASH) syndrome is an acronym used to describe a constellation of BRASH. Effective management of BRASH syndrome often requires a multidisciplinary approach within the intensive care unit and consists of cessation of offending agents, potassium lowering measures, renal replacement therapy, hemodynamic pressor support, and/or cardiac pacing.

- Citation: Pavlatos NT, Daga P, Smiley Z, Belur A, Bhattacharya P, Khan R. Critical presentation of bradycardia, renal failure, atrioventricular nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalemia syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(25): 107948

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i25/107948.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.107948

Bradycardia, renal failure, atrioventricular nodal blockade, shock, and hyperkalemia (BRASH) syndrome is an acronym characterized by the pentad of Bradycardia, Renal failure, Atrioventricular (AV) nodal blockade, Shock, and Hyper

BRASH syndrome was first described by Dr. Joshua Farkas in 2016. Although underdiagnosed, it is likely many physicians have treated BRASH without the benefit of a formal diagnosis or a full understanding of its pathophysiology. Mild cases can be managed with basic medical interventions including fluid resuscitation and treatment of hyperkalemia with more severe cases (characterized by severe, refractory, renal injury, hyperkalemia, and shock) requiring hemodialysis and/or pacing. The two main prognostic factors are the severity of acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia[3,4].

BRASH is mostly seen in the elderly who have underlying cardiac and renal impairment, with common precipitants being dehydration, up-titration of medications that reduce cardiac output, and initiation of nephrotoxic medications[4]. It most commonly presents with encephalopathy, syncope, and/or other signs of decreased cerebral perfusion[5-7].

AV-nodal blocking agents commonly associated with BRASH syndrome are the non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and beta blockers. Although non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem and verapamil) and beta-blockers (e.g. metoprolol and propranolol) are metabolized in the liver, they are still subject to a synergistic interaction with even mild hyperkalemia that can lead to severe bradycardia[8,9]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers also place patients at risk of BRASH through a different mechanism as these medications can lead to both renal failure and hyperkalemia independently[10].

A 54-year-old male presented to the emergency department via emergency medical services with a one-day history of nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath.

The patient was in his normal state of health until the day before presentation, when he developed flu-like symptoms which prompted him to contact emergency medical services.

The patient had a past medical history of diet-controlled type 2 diabetes and hypertension managed with carvedilol and losartan.

The patient had no relevant family medical history.

Physical examination significant for patient was alert and oriented but appeared ill with a heart rate in the 30’s.

Admission labs revealed blood urea nitrogen 79 mg/dL, creatinine 12.97 mg/dL, potassium 9.1 mmol/L, lactic acid 19.2 mmol/Lole/Liter, anion gap 32, and high sensitivity troponin of 6 ng/L.

Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed the patient had an estimated ejection fraction of 70% with no regional wall motion abnormalities.

Patient diagnosed with BRASH syndrome.

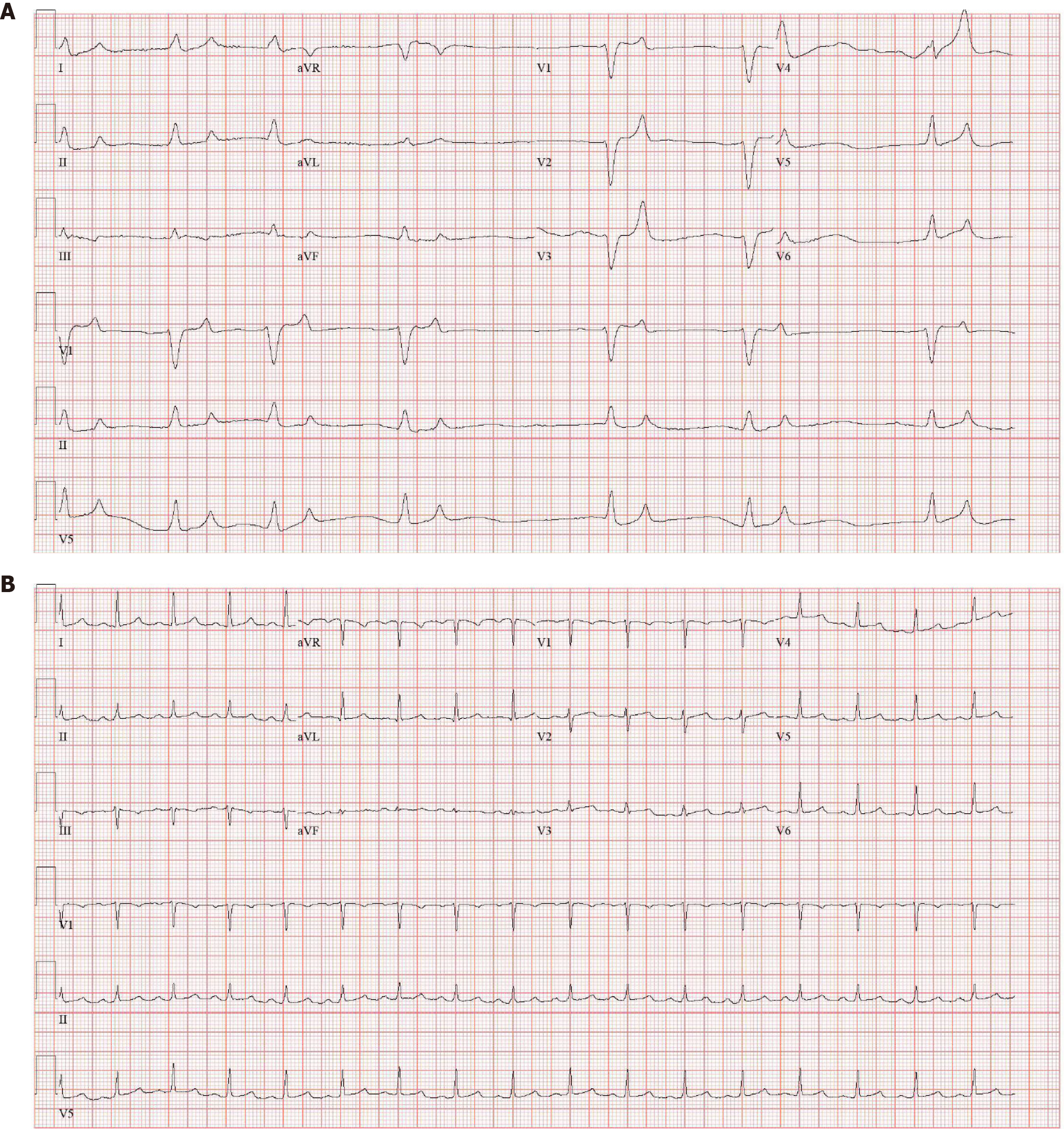

Upon emergency medical services arrival, the patient was bradycardic at 30 beats per minute (BPM) and hypotensive with blood pressure of 74/42 mmHg. Transcutaneous pacing was initiated in the field at a rate of 80 BPM with improvement of his blood pressure to 130/56 mmHg. Pacer pads were removed in the emergency department, and the patient again became bradycardic and hypotensive. Electrocardiogram (EKG) at the time revealed complete heart block with a ventricular rate of 38 BPM and a new left bundle branch block (Figure 1A). He was given atropine 1 mg IV which transiently increased his heart rate to 50 for one minute without any improvement in blood pressure, therefore, transcutaneous pacing was reinitiated. The patient was immediately taken to the Cath Lab where a transvenous pacemaker was placed without complications before transfer to the medical intensive care unit.

Upon admission to the medical intensive care unit, the patient was intubated and placed on vasopressor support with norepinephrine, epinephrine, phenylephrine, and vasopressin. His home medications of carvedilol and losartan were discontinued. He was given intravenous insulin, sodium polystyrene sulfonate, albuterol, and calcium gluconate for acute management of his hyperkalemia followed by continuous renal replacement therapy for 20 hours. Following continuous renal replacement therapy, acute kidney injury, hyperkalemia, and acidosis resolved. On day two of hospitalization both his creatinine and potassium would lower to 2.98 mg/dL and 5.0 mmol/L respectively.

He demonstrated rapid clinical improvement, being extubated on day two of hospitalization and hemodynamically stable, completely off all vasopressor support on day three. He would maintain adequate urine output throughout his hospital course. Once the patient was clinically stable, and renal function had improved, he underwent left heart catheterization which showed non-obstructive coronary artery disease of the distal left anterior descending artery. Renal function remained stable after coronary angiography with no concern for contrast induced nephropathy. Creatinine and potassium at the time of discharge was 1.62 mg/dL and 3.8 mmol/L respectively. EKG at the time of discharge revealed normal sinus rhythm with a ventricular rate of 100 BPM (Figure 1B). The patient continues to do well at subsequent follow-up visits.

BRASH syndrome is a complex disease that involves a cycle of renal failure leading to impaired excretion of potassium and AV nodal blockers. Although approximately 50% of reported cases present with a junctional escape rhythm, BRASH can manifest itself in the form of other bradyarrhythmias as well, such as sinus bradycardia or as with our patient, atrial fibrillation[11]. For this reason, BRASH should be on the differential for those who present with symptomatic bradycardia, especially in the setting of abnormal renal function and hyperkalemia.

Although the pathophysiology is understood, very little is known regarding the epidemiology of the disease as it was first described within the last decade. A recent meta-analysis of seventy cases of BRASH syndrome found that the majority present with modest hyperkalemia (less than 6.5 mmol/L) and can be seen as low as 5.1 mmol/L. Additionally, it was reported that most cases of BRASH can be managed medically with only 20% requiring renal replacement therapy and 33% requiring any forms of pacing. The same study revealed a mortality rate of 5.6%[11].

It has been established that the severity of kidney injury and degree of hyperkalemia are the two most important factors when predicting mortality[3]. Our patient presented with a potassium of 9.1 mmol/L and a creatinine of 12.97 mg/dL. Beyond this, our patient was in severe cardiogenic shock in the setting of normal ejection fraction as evidenced by his lactic acid of 19.2 mmol/Liter and anion gap of 32. What distinguishes this case from others is the level of severity which required a uniquely comprehensive combination of interventions. Although most cases are managed medically in a relatively straightforward manner, our patient required continuous renal replacement therapy, cardiac pacing, and utilization of four different pressors. It is believed that our patient developed BRASH syndrome due to hypovolemia from nausea/vomiting prior to admission, and we attribute our patient’s favorable outcome to the rapid diagnosis of BRASH and early intervention.

Although BRASH syndrome can be life threatening, it is rarely considered in the clinical setting likely due to low awareness and only limited cases described in literature. With a growing elderly population and continued use of medications affecting AV nodal conduction, the incidence of this condition is likely to increase with time. Providers should not only be aware that such a condition exists but also understand the pathophysiology behind the process to best treat it.

| 1. | Farkas J. Pulmcrit- brash syndrome: Bradycardia, renal failure, AV blocker, shock, hyperkalemia. EMCrit Project. Available from: https://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/brash-syndrome-bradycardia-renal-failure-av-blocker-shock-hyperkalemia/. |

| 2. | Farkas JD, Long B, Koyfman A, Menson K. BRASH Syndrome: Bradycardia, Renal Failure, AV Blockade, Shock, and Hyperkalemia. J Emerg Med. 2020;59:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ata F, yasir M, Javed S, Bilal ABI, Muthanna B, Minhas B, Chaudhry HS. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of BRASH syndrome. Med: Case Rep Study Protoc. 2021;2:e0018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Lizyness K, Dewald O. BRASH Syndrome. 2025 Feb 15. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Majeed H, Khan U, Khan AM, Khalid SN, Farook S, Gangu K, Sagheer S, Sheikh AB. BRASH Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Reported Cases. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48:101663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shah P, Gozun M, Keitoku K, Kimura N, Yeo J, Czech T, Nishimura Y. Clinical characteristics of BRASH syndrome: Systematic scoping review. Eur J Intern Med. 2022;103:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Grigorov MV, Belur AD, Otero D, Chaudhary S, Grigorov E, Ghafghazi S. The BRASH syndrome, a synergistic arrhythmia phenomenon. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33:668-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McKeever RG, Patel P, Hamilton RJ. Calcium Channel Blockers. 2024 Feb 22. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Mehvar R, Brocks DR. Stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of beta-adrenergic blockers in humans. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2001;4:185-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arif AW, Khan MS, Masri A, Mba B, Talha Ayub M, Doukky R. BRASH Syndrome with Hyperkalemia: An Under-Recognized Clinical Condition. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020;16:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Majeed H, Khan A, Khalid SN, Khan U, Petrechko O, Sagheer S, Sheikh AB. Brash Syndrome: A Systemic Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:591. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/