Published online Sep 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.106089

Revised: April 9, 2025

Accepted: May 18, 2025

Published online: September 6, 2025

Processing time: 141 Days and 5.8 Hours

A 56-year-old female presented with acute abdominal pain due to a ruptured pseudoaneurysm associated with median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS), a rare condition caused by the compression of the celiac artery by the median arcuate ligament (MAL), potentially leading to ischemia, aneurysm formation, and rupture.

Computed tomography revealed a retroperitoneal hematoma, celiac artery stenosis, and two aneurysms in the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. Hemo

This case highlights the importance of the early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management of MALS.

Core Tip: This case report describes a rare clinical course of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) presenting with a ruptured aneurysm followed by duodenal stenosis after transcatheter arterial embolization. The patient required early surgical treatment, including gastrojejunostomy and decompression via median arcuate ligament transection. The combination of vascular and gastrointestinal complications highlights the importance of multidisciplinary management and timely intervention in patients with complex MALS.

- Citation: Tanikawa T, Miyake K, Kawada M, Ishii K, Fushimi T, Urata N, Wada N, Nishino K, Suehiro M, Kawanaka M, Shiraha H, Haruma K, Fujiwara H, Yamatsuji T, Kawamoto H. Aneurysm rupture in median arcuate ligament syndrome leading to duodenal stenosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(25): 106089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i25/106089.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i25.106089

The median arcuate ligament (MAL) is a fibrous arch formed by fusion of the right and left crura of the diaphragm. It is located anterior to the aorta, at the level of the T12 vertebra, where the aorta passes through the diaphragm. The MAL plays a crucial role in supporting the diaphragm and protecting the aorta during the passage. However, in a few patients, the MAL can compress the origin of the celiac artery, resulting in a condition known as MAL syndrome (MALS). MALS was first reported in 1968 by Harjola and Lahtiharju[1]. Although considered a rare disease, previous reports have documented cases that were either asymptomatic or diagnosed only after rupture of an associated aneurysm[2-4]. A delayed diagnosis of MALS can lead to a decline in the quality of life. Aneurysm rupture can result in severe complications. Therefore, MALS is considered to be an important disease. Herein, we report a case of MALS diagnosed because of aneurysmal rupture that presented with a rare clinical course, including duodenal stenosis following hemostasis. This case is significant because it highlights a rare clinical course in which a ruptured aneurysm associated with MALS leads to secondary duodenal stenosis, ultimately requiring surgical intervention. Such sequences have been reported infrequently and may expand our current understanding of MALS-related complications.

A 56-year-old female presented with upper abdominal pain and cold sweats.

Three days before admission (day-3), she experienced spontaneous resolution of similar abdominal pain. On day 0, she returned to the emergency department with recurrent symptoms, prompting further evaluation.

She had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or other significant medical conditions.

She had never smoked or consumed alcohol. No notable family history exists.

Her vital signs were stable, with a pulse rate of 90 bpm and a blood pressure of 136/84 mmHg. Abdominal distension was noted without tenderness.

Laboratory data on day 0 revealed white blood cell 10070/μL, hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL, and C-reactive protein 2.26 mg/dL.

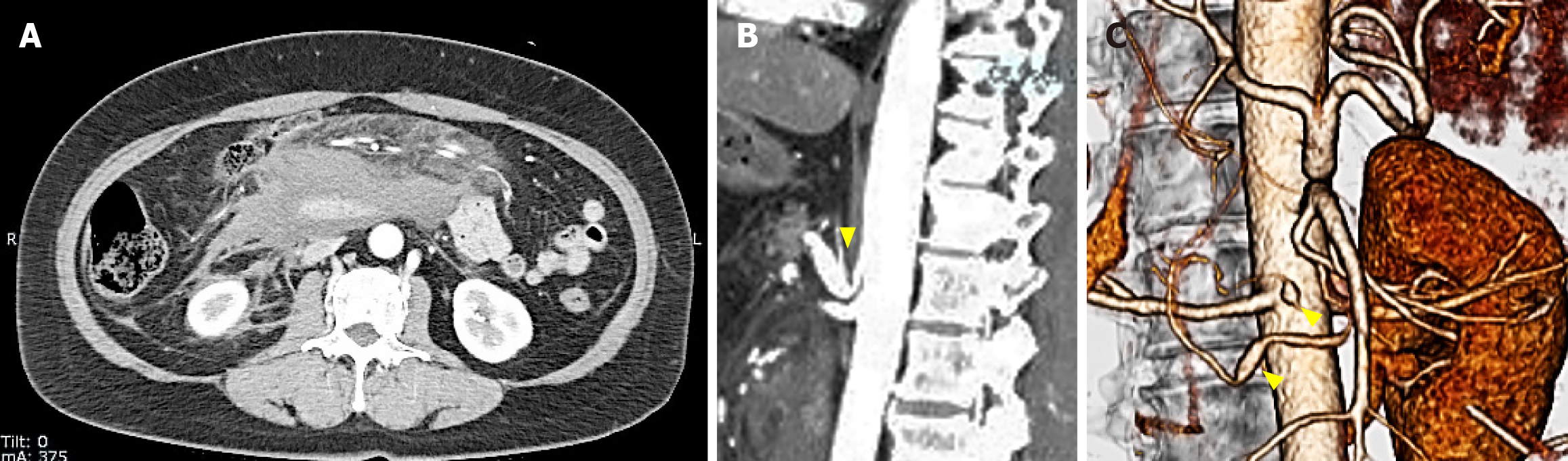

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) on day 0 showed a large retroperitoneal hematoma, smaller hematomas in the pelvic cavity (Figure 1A), stenosis at the origin of the celiac artery (Figure 1B), and two aneurysms in the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (Figure 1C).

On day 0, the patient was reviewed by a multidisciplinary team, including gastroenterologists, interventional radiologists, and surgeons. We agreed to proceed with embolization to achieve hemostasis as the first-line intervention because of its minimally invasive nature and effectiveness in emergency hemorrhage control.

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to a ruptured pseudoaneurysm associated with MALS, complicated by post-embolization duodenal stenosis.

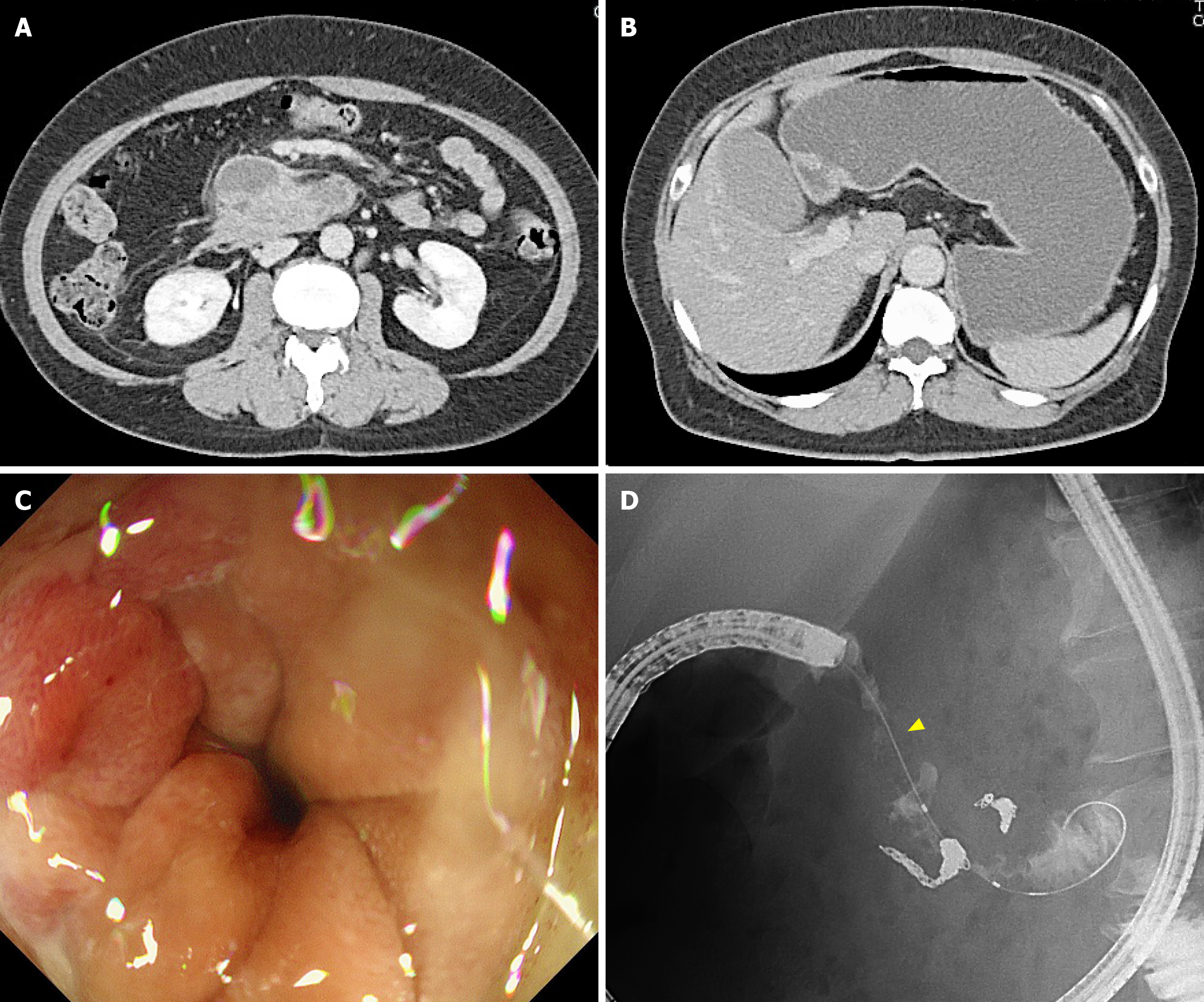

On day 0, interventional radiology was performed to achieve hemostasis via an approach through the right femoral artery. Angiography revealed two aneurysms in the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (Figure 2A). The anterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery was embolized using four microcoils (Figure 2B). Additionally, angiography of the celiac artery revealed stenosis at its root, consistent with MALS findings. After transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), no abdominal pain, signs of acute pancreatitis, or anemia were observed. The patient was discharged on day 8 after stabilization. On day 23, she was readmitted due to gastric distension and nausea. She did not experience any abdominal pain. A CT scan revealed a trend of hematoma reduction; however, gastric distension was observed without any dilation of the duodenum (Figure 3A and B). Gastric passage obstruction due to duodenal stenosis was suspected. Endoscopic observation revealed duodenal stenosis extending from the superior duodenal angle to the third portion of the duodenum. A standard upper endoscope cannot pass through the stenosis, an ultra-slim upper endoscope. The duodenal mucosa showed mild redness and edematous changes, but no mucosal damage such as erosion or ulcers was observed (Figure 3C and D). Despite the reduction of the retroperitoneal hematoma, duodenal stenosis occurred. We considered that the cause of this was not compression of the hematoma but edematous changes due to chemical inflammation of the hematoma. The stenosis was expected to be reversible. However, the stenosis worsened further, and no fluid passed through. Conservative treatment was continued for 12 days without improvement. Because the patient desired a quicker recovery, surgical treatment was decided, including MAL transection and gastrojejunostomy, on day 35.

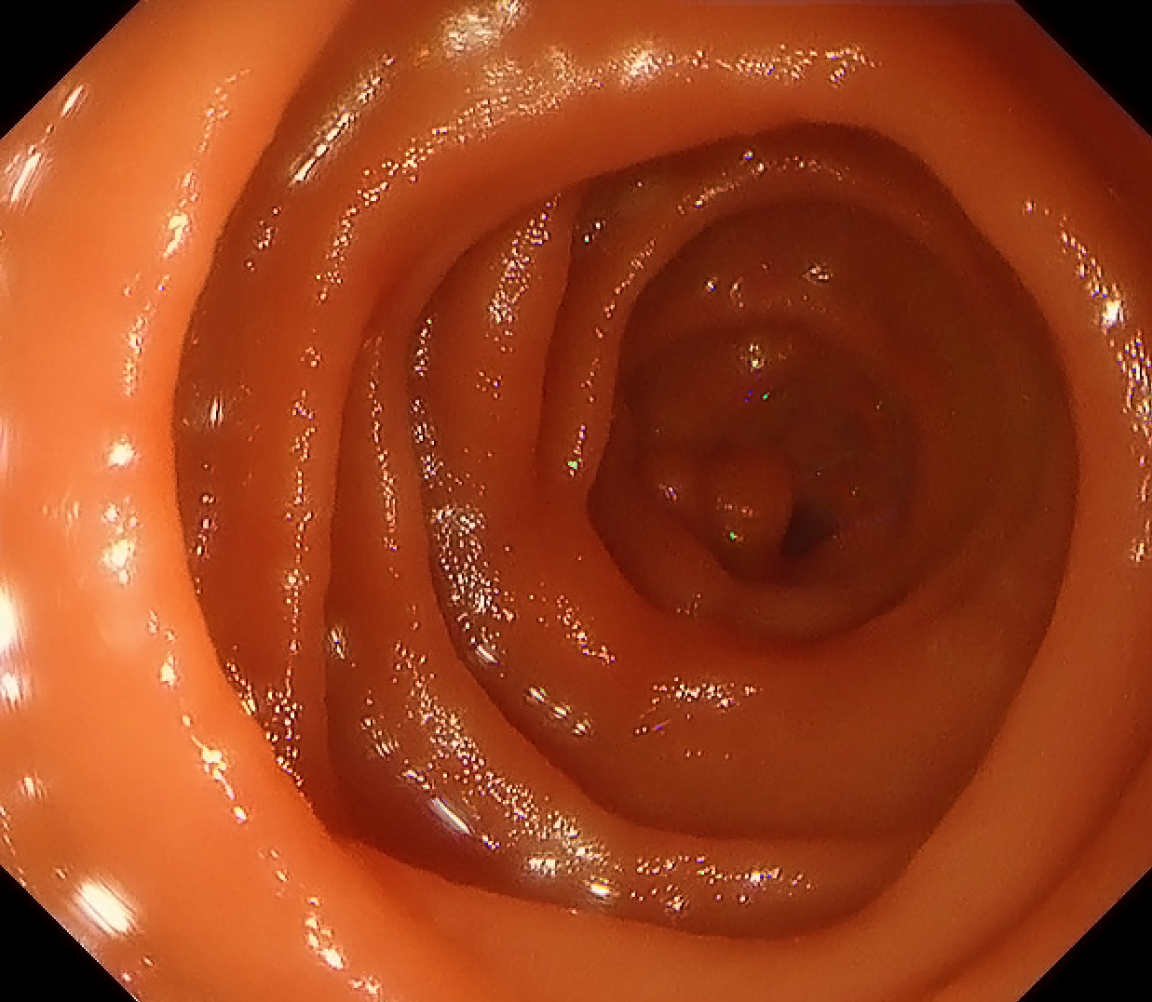

The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged 12 days postoperatively. At the 4-month follow-up, endoscopy showed full resolution of the duodenal stenosis (Figure 4) and no recurrence of the aneurysm.

MALS is a rare condition characterized by the compression of the celiac artery by the MAL, which can lead to gastrointestinal ischemia and, in some cases, aneurysm formation[5-8]. Many patients remain asymptomatic, aneurysms associated with MALS rupture, and present as emergencies[2-4]. Celiac artery compression by MAL has been reported in up to one-third of autopsy cases and in 6.7% of asymptomatic patients on CT imaging[9,10]. This finding may reflect, at least in part, the dynamic nature of celiac artery compression influenced by the respiratory phase, particularly expiration, which can exaggerate narrowing on imaging[10]. This suggests that many patients may be asymptomatic. Aneurysm formation is another consequence of celiac artery compression, often resulting from increased blood flow that compensates for gastrointestinal ischemia. A few patients with MALS have been diagnosed after the rupture[2-4]. In our case, the patient was diagnosed with an aneurysm rupture despite the absence of MALS-related abdominal symptoms prior to the event. The rupture of a pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm, which represents 2% of splanchnic aneurysm ruptures[11-13], is a clinical emergency in nearly 22% of cases and requires urgent treatment[14]. Treatment options for pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm rupture include surgical hemostasis and TAE, with TAE being the preferred choice due to its minimally invasive nature. However, TAE alone may not adequately control aneurysmal rupture. Hofmann et al[15] reported a case of MALS in which aneurysm rupture recurred after TAE. In our case, surgical splitting of the MAL was performed to correct abnormal blood flow. No postoperative aneurysm recurrence was observed. In this case, duodenal stenosis occurred 15 days after TAE. Nakayama et al[16] showed that three types of duodenal stenosis can occur after TAE. The acute phase was defined as within 1 week, the subacute phase was defined as > 1 week but within 1 month, and the chronic phase was defined as > 1 month. In that report, the median period between the onset of duodenal stenosis and TAE was 10 days, and duodenal stenosis occurred in 83% of cases in the subacute stage. In this case, it occurred 15 days after TAE in the subacute phase. Duodenal ischemia, mechanical compression due to hematoma, and duodenal fibrotic encasement have been reported as causes of this condition[17-19]. In our case, despite a reduction in the retroperitoneal hematoma, duodenal stenosis occurred. Additionally, the duodenal mucosa exhibited only edematous changes. Acute pancreatitis is a known complication of TAE. It is possible that inflammation of acute pancreatitis could extend to the surrounding tissues and result in duodenal stenosis. However, in the present case, there was no evidence of acute pancreatitis following TAE. Therefore, duodenal stenosis was suspected to have been caused by inflammation due to ischemia after TAE. Blood supply to the duodenum is primarily provided by branches of the superior mesenteric artery and the gastroduodenal artery, which form an interconnected arcade. This vascular arrangement helps maintain adequate perfusion even if one of the supplying vessels is compromised by TAE, thus reducing the likelihood of duodenal ischemia[20]. Although TAE reduced the blood supply to the duodenum, leading to edematous changes in the mucosa, it prevented complete ischemia. In previous reports, duodenal edematous changes after TAE improved with conservative treatment in most cases[16]. However, Kwon et al[17] reported that conservative treatment did not improve, and surgical intervention was performed on the 24th day after TAE. Our patient required a long period for the improvement of duodenal stenosis. Therefore, we performed a gastrojejunostomy simultaneously with MAL transection. The edematous changes in the duodenal mucosa disappeared 4 months after surgery. In this case, the embolized artery was the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which directly contributes to duodenal perfusion. Although the duodenum has rich collateral flow, embolization of this major arcade component may lead to localized ischemia or inflammation, predisposing the patient to duodenal stenosis[16,20]. Our case reinforces the idea that conservative treatment is often sufficient; a few patients may require timely surgical management. These findings suggest that patients diagnosed with MALS, particularly those presenting with aneurysmal rupture and persistent duodenal stenosis, may benefit from long-term vascular monitoring. When conservative measures fail, early surgical intervention may prevent recurrence and improve outcomes.

This case illustrates a rare but clinically important course of MALS, beginning with an arterial aneurysm rupture and progressing to duodenal stenosis after embolization. Early diagnosis, appropriate vascular and gastrointestinal monitoring, and timely interventions are essential. Further research is needed to establish optimal strategies for managing post-embolization complications of MALS, particularly regarding the timing and indications for surgical intervention.

| 1. | Harjola PT, Lahtiharju A. Celiac axis syndrome. Abdominal angina caused by external compression of the celiac artery. Am J Surg. 1968;115:864-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Okuno N, Maruyama S, Wada D, Komemushi A, Shimazu H, Kanayama S, Saito F, Nakamori Y, Kuwagata Y. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to ruptured artery induced by median arcuate ligament syndrome in patients with COVID-19: A case series. Acute Med Surg. 2024;11:e70015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arino H, Wada M, Kobayashi H, Yoshida A, Oka S, Inokuma T. Metachronous Rupture of Pancreatoduodenal Artery Aneurysm with Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of 11 Cases. Intern Med. 2025;64:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abe K, Iijima M, Tominaga K, Masuyama S, Izawa N, Majima Y, Irisawa A. Retroperitoneal Hematoma: Rupture of Aneurysm in the Arc of Bühler Caused by Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2019;12:1179547619828716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim EN, Lamb K, Relles D, Moudgill N, DiMuzio PJ, Eisenberg JA. Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome-Review of This Rare Disease. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:471-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Toriumi T, Shirasu T, Akai A, Ohashi Y, Furuya T, Nomura Y. Hemodynamic benefits of celiac artery release for ruptured right gastric artery aneurysm associated with median arcuate ligament syndrome: a case report. BMC Surg. 2017;17:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heo S, Kim HJ, Kim B, Lee JH, Kim J, Kim JK. Clinical impact of collateral circulation in patients with median arcuate ligament syndrome. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2018;24:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sempere Ortega C, Gallego Rivera I, Shahin M. Gastric ischaemia as an unusual presentation of median arcuate ligament compression syndrome. BJR Case Rep. 2017;3:20160005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lindner HH, Kemprud E. A clinicoanatomical study of the arcuate ligament of the diaphragm. Arch Surg. 1971;103:600-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kazan V, Qu W, Al-Natour M, Abbas J, Nazzal M. Celiac artery compression syndrome: a radiological finding without clinical symptoms? Vascular. 2013;21:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | El Hassani Y, Haloua M, Alami B, Boubbou M, Maaroufi M, Lamrani MYA. Imaging of retroperitoneal haemorrhage revealing median arcuate ligament syndrome. SA J Radiol. 2021;25:1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kaszczewski P, Leszczyński J, Elwertowski M, Maciąg R, Chudziński W, Gałązka Z. Combined Treatment of Multiple Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms Secondary to Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome: A Case Study and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e926074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Tan EWK, Shelat VG, Monteiro AY, Low JK. Spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage from pancreatoduodenal artery (PDA) rupture and associated complications. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e250383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stanley JC. Abdominal visceral aneurysms. In: Haimovici H, editor. Vascular emergencies. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1981: 387-397. |

| 15. | Hofmann K, Lareida A, Bächler T, Breitenstein S, Kambakamba P. Recurrent aneurysmatic bleeding of pancreaticoduodenal aneurysm due to median arcuate ligament syndrome: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2024;2024:rjae364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nakayama K, Shimohira M, Nagai K, Ohta K, Kawai T, Sawada Y, Shibata S, Shibamoto Y. Duodenal stenosis after transcatheter arterial embolization for rupture of an inferior pancreaticoduodenal aneurysm. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:2869-2872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kwon YJ, Kim JH, Kim SH, Kim BS, Kim HU, Choi EK, Jeong IH. Duodenal obstruction after successful embolization for duodenal diverticular hemorrhage: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3819-3822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamoto K, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Toyoda H, Kanamori A, Tada T, Arakawa T, Fujimori M, Niinomi T, Ando N. [Ruptured aneurysm of a posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery associated with duodenal stenosis after transcatheter arterial embolization]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;108:978-986. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Goda K, Yo S, Katsumata R, Fukushima S, Osawa M, Murao T, Ishii M, Fujimura Y, Matsumoto H, Shiotani A. [Duodenal obstruction after transarterial embolization for rupture of a pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm due to segmental arterial mediolysis:a case report]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2019;116:515-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Foltz G, Khaddash T. Embolization of Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Complicated by Bowel Ischemia. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2019;36:76-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/