Published online Aug 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.107098

Revised: April 12, 2025

Accepted: May 10, 2025

Published online: August 26, 2025

Processing time: 93 Days and 14.9 Hours

Gastritis cystica profunda (GCP) is a rare gastric disorder. It is characterized by non-specific symptoms and diagnostic complexity. This case report enriches the medical literature by highlighting challenges in diagnosing and treating GCP.

Two patients presented with non-specific abdominal symptoms, such as abdo

GCP diagnosis demands caution, and endoscopic treatment is effective.

Core Tip: Gastritis cystica profunda (GCP) is a rare and typically asymptomatic condition, with no distinct clinical manifestations, making it prone to being missed or misdiagnosed in clinical practice. In this report, we present two cases of GCP diagnosed and treated at our hospital. The report aims to enhance the understanding of GCP occurrence and provide guidance for timely and accurate diagnosis.

- Citation: Zheng XL, Xu L, Wang J. Initial misdiagnosis of gastritis cystica profunda: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(24): 107098

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i24/107098.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.107098

Gastritis cystica profunda (GCP) is an infrequently encountered gastric disorder characterized by the abnormal growth of glandular tissue into the mucosa and submucosa of the stomach[1]. The exact pathogenesis remains elusive, but it is hypothesized to involve a combination of congenital and acquired factors. Congenital ectopic glands might serve as a starting point, while acquired factors such as gastric surgery trauma, peptic ulcer-related inflammation, foreign body-induced irritation, or the reflux of digestive juices such as bile could trigger the migration and cystic dilation of these glands in the submucosa[2].

Clinically, GCP poses a significant diagnostic challenge. Its manifestations are non-specific, often overlapping with those of other common gastric conditions[3]. Patients typically present with non-specific digestive symptoms, such as epigastric pain, discomfort, anorexia, and acid reflux. In some cases, more severe symptoms like gastric mucosal erosion, leading to upper abdominal pain and bleeding (manifested as hematemesis or melena), may occur. However, these symptoms are not exclusive to GCP and can be seen in a wide range of gastric diseases[4]. Routine laboratory tests, including blood counts and biochemical analyses, rarely provide conclusive evidence for GCP diagnosis, as they usually yield normal results. Although gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography play crucial roles in detecting potential GCP lesions, they are not definitive diagnostic tools. Gastroscopy may reveal various endoscopic appearances, such as mucosal lesions, polypoid protrusions, submucosal protrusions, or mucosal hypertrophy with thickened folds. Endoscopic ultrasonography often shows multiple hypoechoic areas within the submucosa or muscularis propria, sometimes accompanied by anechoic cystic structures[1]. However, these imaging features are not pathognomonic for GCP and can be mimicked by other gastric disorders like submucosal tumors, gastric polyps, and lymphoma.

As a result, preoperative diagnosis of GCP is frequently inaccurate, and misdiagnosis is common in clinical practice. In this report, we present two cases of GCP that were initially misdiagnosed, one as a submucosal tumor and the other as a gastric polyp. By sharing these cases, we aim to enhance the understanding of GCP’s diagnostic challenges and contribute to improving the accuracy of its diagnosis in future clinical practice.

Case 1: A 46-year-old male patient presented with persistent abdominal distension of unknown etiology, which had lasted 3 months. This abdominal distension was not accompanied by other associated symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting.

Case 2: A 37-year-old female reported a 2-year history of intermittent epigastric discomfort. The discomfort was described as a dull, non-specific sensation. She did not experience concurrent symptoms like abdominal pain radiating to other areas, hematemesis, melena, or significant changes in appetite or bowel habits during this period.

Case 1: Three months ago, the patient presented with persistent abdominal distension. This symptom was not accompanied by abdominal pain, suggesting no acute peritoneal or visceral inflammatory processes. There was also no diarrhea, ruling out infectious or malabsorptive etiologies commonly associated with abdominal distension.

Case 2: The patient had a two-year history of intermittent epigastric discomfort. This discomfort occurred sporadically. She did not experience abdominal pain, which would be concerning for peptic ulceration or gastritis. There were no episodes of hematemesis or melena, indicating the absence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. No specific medical treatment was sought during this period.

Both patients had an unremarkable past medical history. There were no chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, or autoimmune disorders. In the context of the digestive system, neither had a history of peptic ulcers, gastritis, or gastric surgeries. There were no known infections with Helicobacter pylori, and no previous significant gastrointestinal infections.

Both patients had an unremarkable personal and family history, with no chronic diseases or gastrointestinal disorders.

In both patients, cardiac auscultation detected regular heart rhythms, without murmurs, gallops, or abnormal heart sounds. Pulmonary examination, including percussion and auscultation, showed clear lung fields bilaterally, with no adventitious sounds such as rales, wheezes, or rhonchi. Abdominal inspection revealed a flat and symmetric abdomen, without visible masses, distension, or abnormal pulsations. On palpation, there was no tenderness, muscle guarding, or rebound tenderness. The liver and spleen were not palpable below the costal margins, and no masses were detected in the abdominal cavity. Bowel sounds were normal in frequency and character, indicating no signs of bowel obstruction or hyperactivity.

In both patients, comprehensive blood analysis results, including complete blood count, blood biochemical tests such as liver and kidney function, and lipid profiles, were all within the normal reference range. The white blood cell count, red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and platelet levels were normal, indicating no signs of infection, anemia, or bleeding disorders. Liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase, along with kidney-related markers including creatinine and urea nitrogen, were within the normal ranges, suggesting normal hepatic and renal function.

Stool analysis also showed no abnormalities. There was no occult blood detected in the feces, ruling out the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding. Stool appearance, consistency, and microscopic examination for parasites, ova, and white blood cells were all negative. Furthermore, serum tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and alpha-fetoprotein, were all within the normal limits.

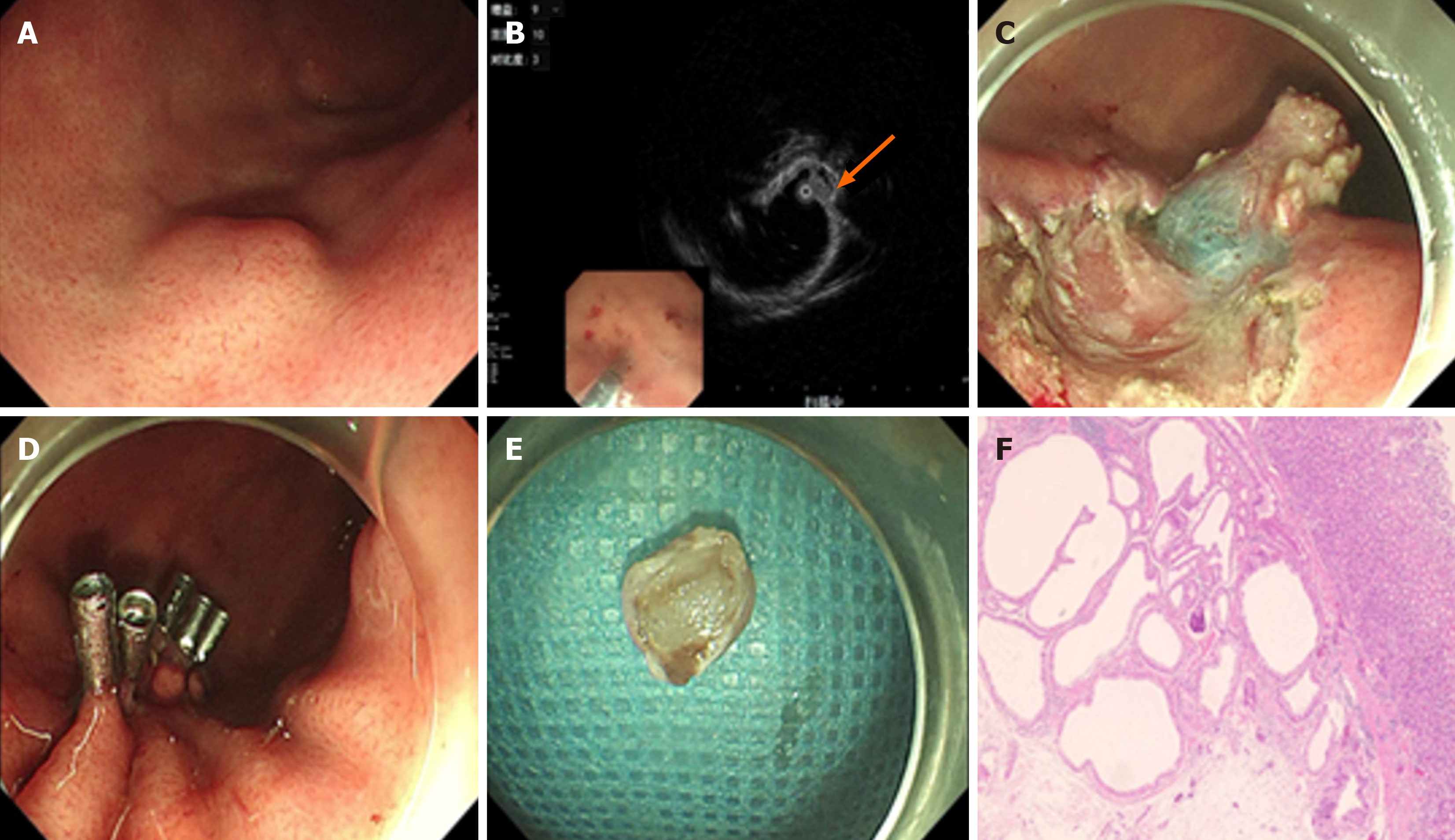

Case 1: Gastroscopy disclosed a submucosal mass approximately 1.2 cm × 0.8 cm on the greater curvature of the gastric fundus. The mucosal surface over the mass was smooth, presenting no signs of inflammation, ulceration, or irregular texture (Figure 1A). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed that the lesion was situated in the submucosal layer. It manifested as a hypoechoic nodule measuring about 1.0 cm × 0.8 cm, with multiple anechoic sacs inside, and its boundaries were clearly demarcated (Figure 1B). An abdominal computed tomography scan failed to detect any obvious abnormalities, such as abnormal densities, masses, or structural changes in the abdominal cavity.

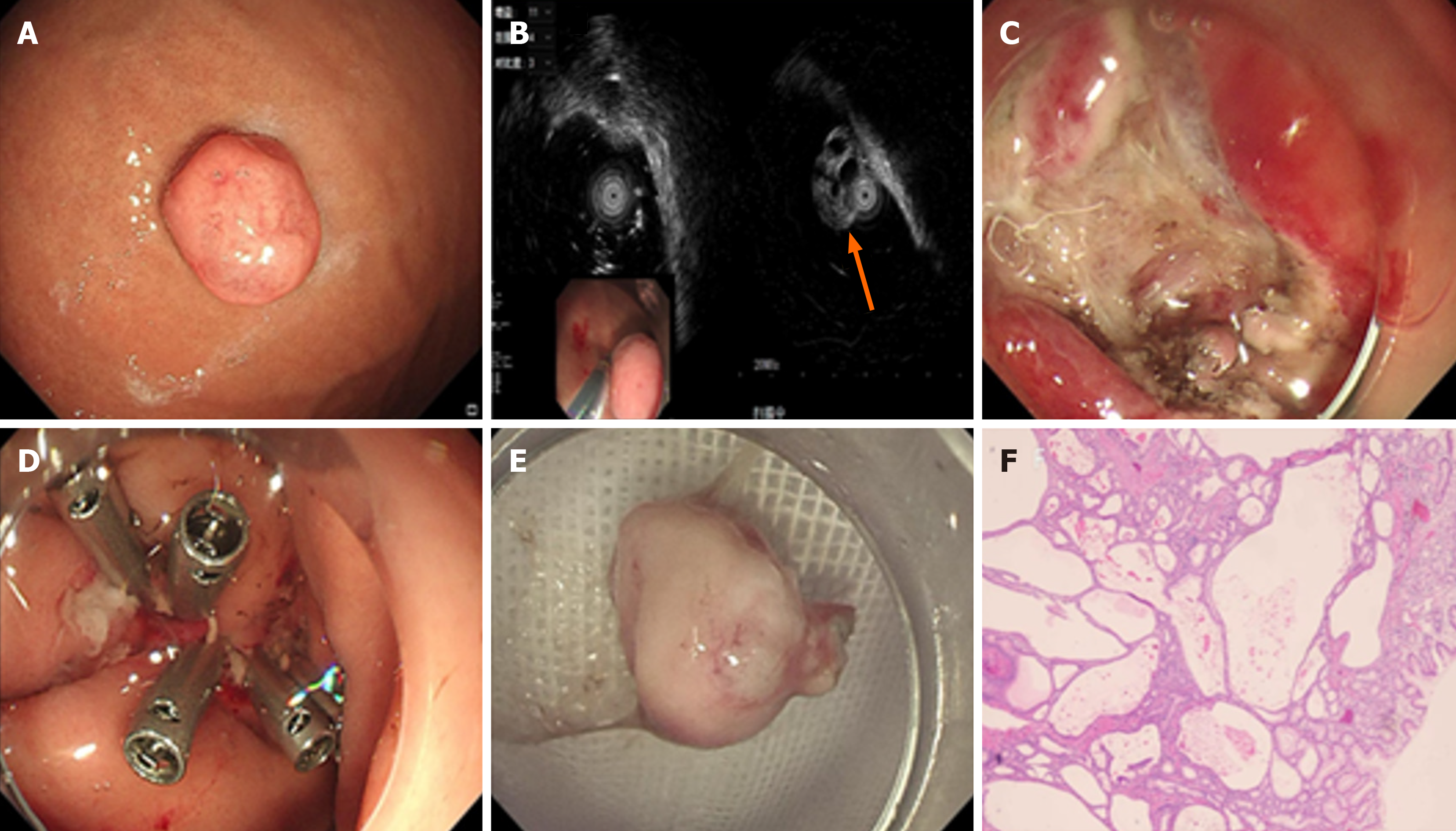

Case 2: Gastroscopy detected a pedunculated polypoid lesion on the greater curvature of the gastric body (Figure 2A). EUS further identified a solid-cystic lesion within the mucosal layer, approximately 1.3 cm × 1.0 cm in size (Figure 2B). This solid-cystic appearance suggested a complex internal structure, which might be composed of both solid tissue components and cystic spaces.

Microscopic analysis revealed an incomplete continuity of the mucosal muscle layer, elongation of gastric pits, and cystic expansion and hyperplasia of gastric glands, which are the characteristic pathological features of GCP. Based on the histopathological findings following endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), the final diagnosis was GCP.

After endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), the histopathological examination indicated polypoid cystic gastritis, which is consistent with the diagnosis of GCP. The histological examination showed that the gastric mucosa had glandular hyperplasia and cystic dilatation, along with an intact mucosal surface in most areas. These findings, in combination with the absence of features suggesting other gastric pathologies, led to the final diagnosis of GCP, correcting the initial misdiagnosis of a gastric polyp.

Case 1 chose ESD. During the ESD procedure, the endoscopist used specialized instruments to carefully dissect the lesion from the submucosal layer. The operation was successful, with no complications such as bleeding or perforation. Complete resection of the lesion was achieved, as verified by post-operative examination (Figure 1C-E). This not only removed the suspected abnormal tissue but also provided a specimen for accurate histopathological diagnosis.

The patient underwent EMR. After excising the pedunculated polypoid lesion, the endoscopic surgeon used titanium clips to close the wound. Titanium clips are highly effective in securing the mucosal edges, reducing the risk of bleeding and promoting wound healing. The use of EMR and titanium clip closure ensured safe and efficient removal of the lesion, enabling histological analysis for an accurate diagnosis (Figure 2C-E).

Post-operative histopathological examination of the resected specimen from confirmed the diagnosis of GCP. Microscopic analysis demonstrated characteristic features such as glandular cystic dilation extending into the submucosa, elongation of gastric pits, and disruption of the mucosal muscle layer (Figure 1F). The patient experienced an uncomplicated recovery. There were no signs of surgical site infection, bleeding recurrence, or other post-operative complications. Based on the patient's stable condition, he was discharged 5 days after the surgery.

Histopathological examination of the tissue revealed polypoid cystic gastritis, which is in line with the diagnosis of GCP. The histological findings showed glandular hyperplasia and cystic changes within the gastric mucosa (Figure 2F). The patient's recovery was uneventful. The wound site, which was closed with titanium clips during the EMR, healed well without any signs of dehiscence, infection, or bleeding. Given the patient's good condition, she was discharged 3 days after the procedure.

Historically GCP is considered a benign condition, contemporary research, propelled by immunohistochemistry and molecular biology progress, hints at its potential as a precancerous state[5]. This shift in perception underlines the significance of accurate diagnosis and timely intervention.

GCP predominantly affects middle-aged and elderly men. Lesions are most frequently detected in the gastric antrum and body, but the fundus and cardia can also be implicated. Clinically, GCP presents a confounding array of non-specific symptoms. In the present report, Case 1 presented with abdominal distension and Case 2 presented with epigastric discomfort. Patients commonly report indigestion-like symptoms such as epigastric pain, discomfort, anorexia, and acid reflux. In more severe cases, gastric mucosal erosion can occur, leading to intense upper abdominal pain and bleeding manifestations, including hematemesis and melena[6]. Routine laboratory tests, like blood counts and biochemical panels, rarely show significant abnormalities, adding to the diagnostic complexity.

Gastroscopy and EUS are crucial diagnostic tools. The endoscopic manifestations of GCP are diverse, falling into four main categories: Mucosal lesions, polypoid protrusions, submucosal protrusions, and mucosal hypertrophy with thickened folds. In our two cases, one demonstrated a submucosal protrusion, while the other had a polypoid protrusion. EUS has seen marked improvements in its diagnostic utility. For GCP, it typically reveals multiple hypoechoic areas within the submucosa or muscularis propria, often associated with anechoic cystic structures[7]. However, it is important to note that such heterogeneous cystic masses in the submucosa are not exclusive to GCP, as was evident in our cases where ultrasonic gastroscopy showed heterogeneous hypoechoic nodules with anechoic sacs. This highlights the need for a comprehensive diagnostic approach.

Pathological examination remains the gold standard for definitive GCP diagnosis. Histologically, GCP is characterized by an incomplete mucosal muscle layer, elongated gastric pits, and cystic expansion and hyperplasia of the gastric glands[8]. Integrating endoscopic and pathological evaluations is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

In terms of treatment, currently, there are no standardized guidelines for GCP. Management mainly encompasses endoscopic and surgical approaches. Recent advancements in endoscopic resection techniques have enhanced their safety and effectiveness. Compared to traditional surgery, endoscopic treatments offer multiple benefits, including shorter operative times, reduced costs, and greater safety. Significantly, these minimally invasive procedures preserve the stomach's physiological structure, minimizing patient trauma[9]. Thus, when GCP is diagnosed and there are no co-existing malignant lesions or early gastric cancers, and the case meets endoscopic intervention criteria, endoscopic resection should be the first-line treatment option.

Long-term follow-up is crucial for GCP patients, regardless of the treatment method. Given the potential precancerous nature of GCP and the lack of a well-defined recurrence rate, regular endoscopic surveillance can detect early signs of recurrence or disease progression, enabling timely intervention. In conclusion, while GCP remains diagnostically challenging, a combination of improved diagnostic techniques, proper treatment selection, and vigilant follow-up can enhance patient outcomes. Further research is needed to refine diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment strategies, and better understand the pathogenesis of GCP.

This study reported two cases of GCP that were initially misdiagnosed, one as a submucosal tumor and the other as a gastric polyp, primarily because of their non-specific symptoms like abdominal distension in Case 1 and epigastric discomfort in Case 2, which are common across various gastric conditions, and the limitations of imaging techniques such as gastroscopy and EUS. Histopathological examination is crucial for accurate diagnosis, which reveals characteristic features like cystically dilated glands in the submucosa, glandular hyperplasia, and elongated gastric pits. Endoscopic treatments, including ESD and EMR, effectively removed the lesions with few complications. Given the uncertain recurrence rate of GCP, long-term follow-up with regular endoscopic surveillance is essential. In conclusion, GCP remains diagnostically challenging, and future research should concentrate on understanding its pathogenesis, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and devising more effective treatment strategies to improve outcomes of the patients with this rare gastric disorder.

| 1. | Du Y, Zhang W, Ma Y, Qiu Z. Gastritis cystica profunda: a case report and literature review. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:3668-3677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Haddad GC, Moussallem N, Sbeih S, Karam K, Fiani E. Double the Trouble: A Rare Finding of Gastritis Cystica Profunda in a Previously Unoperated Young Female with Concomitant Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2024;11:004845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Suri C, Pande B, Sahu T, Sahithi LS, Verma HK. Revolutionizing Gastrointestinal Disorder Management: Cutting-Edge Advances and Future Prospects. J Clin Med. 2024;13:3977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | De Stefano F, Graziano GMP, Viganò J, Mauro A, Peloso A, Peverada J, Fellegara R, Vanoli A, Faillace GG, Ansaloni L. Gastritis Cystica Profunda: A Rare Disease, a Challenging Diagnosis, and an Uncertain Malignant Potential: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Bedi HK, Motomura D, Shahidi N. Gastric cystica profunda: Another indication for minimally invasive endoscopic resection techniques? World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3278-3283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Papp V, Miheller P. Chronic active and atrophic gastritis as significant contributing factor to the development of gastric cystica profunda. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2308-2310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu XF, Guo LW, Chen ST, Teng LS. Gastritis cystica profunda in a previously unoperated stomach: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3759-3762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (121)] |

| 8. | Wang R, Lu H, Yu J, Huang W, Li J, Cheng M, Liang P, Li L, Zhao H, Gao J. Computed tomography features and clinical characteristics of gastritis cystica profunda. Insights Imaging. 2022;13:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Noh SJ, Kim KM, Jang KY. Gastritis cystica profunda with predominant histiocytic reaction mimicking solid submucosal tumor. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2020;31:726-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/