Published online Jul 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i20.105685

Revised: February 22, 2025

Accepted: March 10, 2025

Published online: July 16, 2025

Processing time: 64 Days and 7.1 Hours

The generation of intrabony defects due to the iatrogenic use of elastic bands is an undesirable situation that can result in persistent gingival inflammation with subsequent bone degradation, thus ultimately leading to tooth loss.

This clinical case involved a 27-year-old male patient who complained of persis

The use of elastic bands of various sizes and elasticities is often essential in multiple orthodontic treatments. However, it is crucial to perform a thorough check-up for each patient during treatment and at the end of treatment to remove any remaining residue of resin, metal bands, or orthodontic bands. Additionally, it is imperative to inform the patients of the importance of attending their follow-up appointments. The use of elastic bands in orthodontics requires special care; moreover, GTR is a management option for intrabony defects associated with the iatrogenic use of bands.

Core Tip: Intrabony defects caused by the iatrogenic use of elastic bands are undesirable. They can result in inflammation, suppuration, and persistent gingival bleeding; these effects, lead to bone degradation and can increase risks to the quality of life of teeth. In the present case, it was impossible to identify the duration in which the elastic bands were invaginated in the periodontal tissue; specifically, the bands may have been invaginated for many years, according to the patient's report. The use of guided tissue regeneration favored the reconstruction of the intrabony defects that were generated by these elastic bands. The use of elastic bands in orthodontics requires special care by both clinicians and patients to avoid iatrogenic effects.

- Citation: Montiel-López PA, García-Nuñez JC, Muro-Jiménez ML, Soto-Chávez AA, Martínez-Rodríguez VM, Rodríguez-Montaño R, Ruiz-Gutiérrez AC. Management of intrabony defects associated with the iatrogenic use of orthodontic elastic bands: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(20): 105685

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i20/105685.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i20.105685

Elastic bands are used in different phases of orthodontic treatment to exert an active force for the generation of dental movement. They have been used to correct gaps, crossbites, and poor dental alignments[1]. In 1870, the use of an elastic band was reported for the first time. Specifically, the band was mistakenly left in place around a tooth in the gingival sulcus, which caused the root to loosen[2]. Elastic bands have also been used to perform atraumatic extractions in patients with hemophilia[2,3] and patients treated with bisphosphonates to reduce bleeding risks and osteonecrosis complications, respectively[4]. In addition, to reduce costs, some patients and dentists have used these bands as a treatment option to close gaps[1]. However, the misuse of elastic bands has been associated with the destruction of periodontal support, tooth mobility[5,6], and subsequent iatrogenic tooth loss[7-10]. This case report presents the management and follow-up of severe bone loss in the upper central and lateral areas due to the iatrogenic use of elastic bands.

A 27-year-old male patient visited the Comprehensive Dental Clinics of the Postgraduate Program in Periodontology at the University of Guadalajara. His main reason for consultation was: “I have periodontitis, and I require treatment”.

The patient reported persistent gingival inflammation in the upper anterior area, despite having undergone dental cleaning for at least 4 years. His general medical history did not demonstrate any pathological data.

With respect to the patient´s dental and medical history, the patient reported having used removable orthodontic appliances for 8 years, after which braces were placed for 2 years. When the fixed appliances were removed, the patient underwent dental cleaning; however, his private dentist reported that he was still experiencing inflammation and bleeding in his gums. Therefore, the dentist referred the patient to the periodontist.

His personal history has been healthy, and he was unaware of any family history of illness.

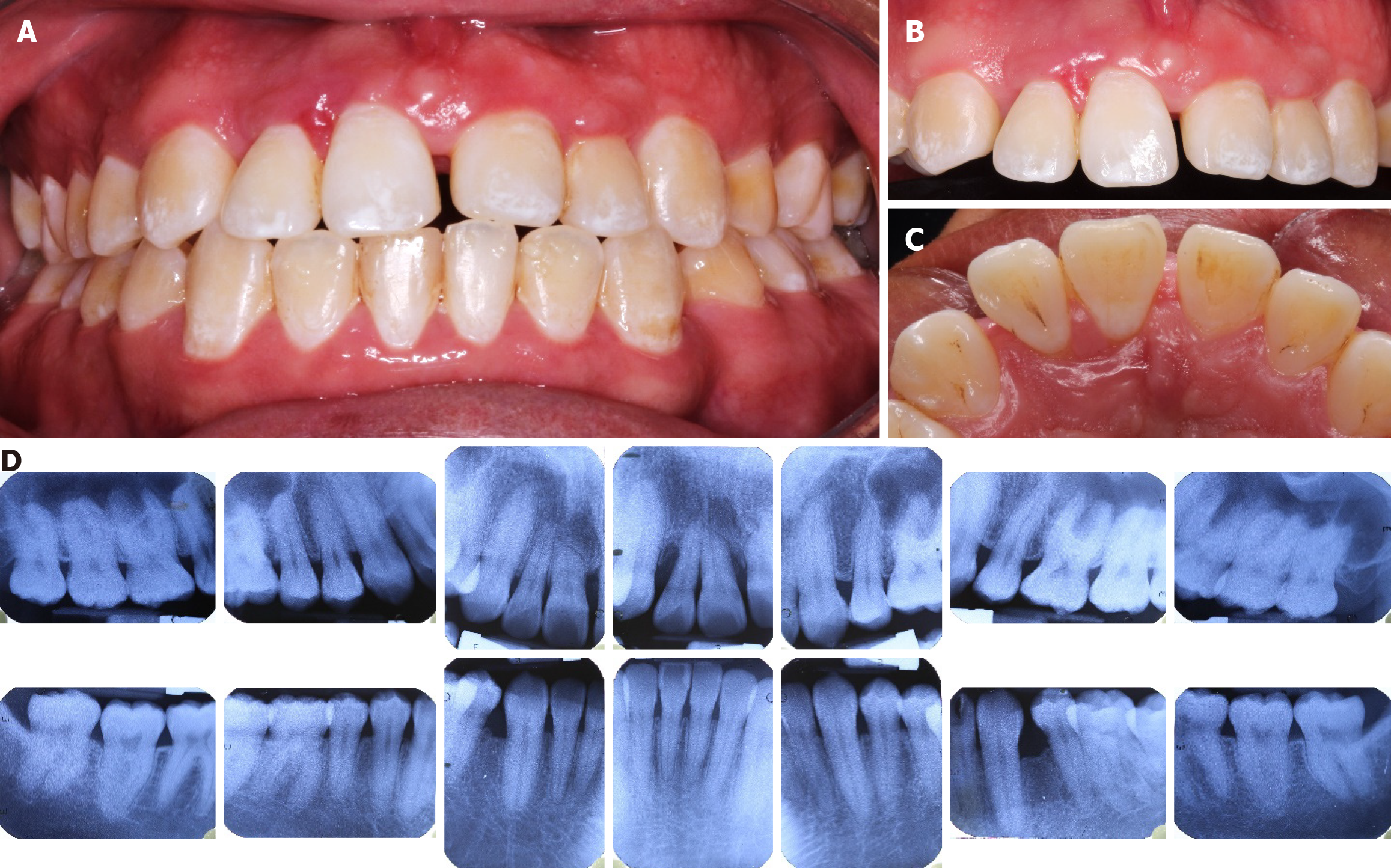

The extraoral examination did not yield any relevant data. Intraorally, the gingival phenotype was thick with inflammation and generalized dental plaque (Figure 1A). The upper anterior sextant exhibited diastemas between teeth 11 and 21 and between teeth 12 and 13, with tooth numbering performed according to the World Dental Federation system[11]. Teeth 11 and 12 were vestibularized, with increased gingival volume, edema, suppuration, and fremitus being observed (Figure 1B). On the palatal surface, there was a horizontal line observed at the base of the interdental papilla (Figure 1C). The initial radiographic examination revealed a combined bone loss in 11, 12, and 21, which exhibited root resorptions at the apexes and root proximity between 11 and 12; in the remaining teeth, there was continuity observed in the hard lamina of the crest, with no relevant data being demonstrated (Figure 1D). In the periodontal chart, the probing depths (PDs) of teeth 12, 11, and 21 ranged from 2-7 mm; clinical attachment loss (CAL) ranged from 1-5 mm; grade II mobility was determined. Both teeth exhibited a positive response to the pulp sensitivity test. PD ranges of 1-3 mm in the remaining teeth were observed, with several locations demonstrating PDs at 4 mm; moreover, there was no observation of CAL or mobility. The percentage of bleeding upon probing (BP) was 77%, and the percentage of plaque or calculus (PoC) was 96%.

Hematologic and blood chemistry tests were performed, and all biochemical parameters were within range.

The periapical radiographic study was taken. The initial radiographic examination was performed via the parallel technique; moreover, the Rinn-type (XCP) positioners, the Corix 70 Junior Digital machine, and periapical radiographs with silver halide film were utilized at 60 kVp and eight mA, with an exposure time of 0.6 seconds. Radiographs that were performed during the maintenance phase (both at six months and two years after surgery) were obtained using the parallel technique with Rinn-type (XCP) positioners, the Corix Plus X-ray machine, and phosphor plate periapical radiographs (captured via the Fire CR brand X-ray scanner by VAMASA) at 60 kVp and eight mA, with an exposure time of 0.3 seconds.

According to the World Workshop Classification 2017, the diagnosis was localized stage III, grade C periodontitis, associated with local factors in teeth 11, 12, and 21, as well as generalized gingivitis related to dental plaque in the remaining teeth[12]. In addition, the patient demonstrated resorption of the dental root of teeth 11 and 12.

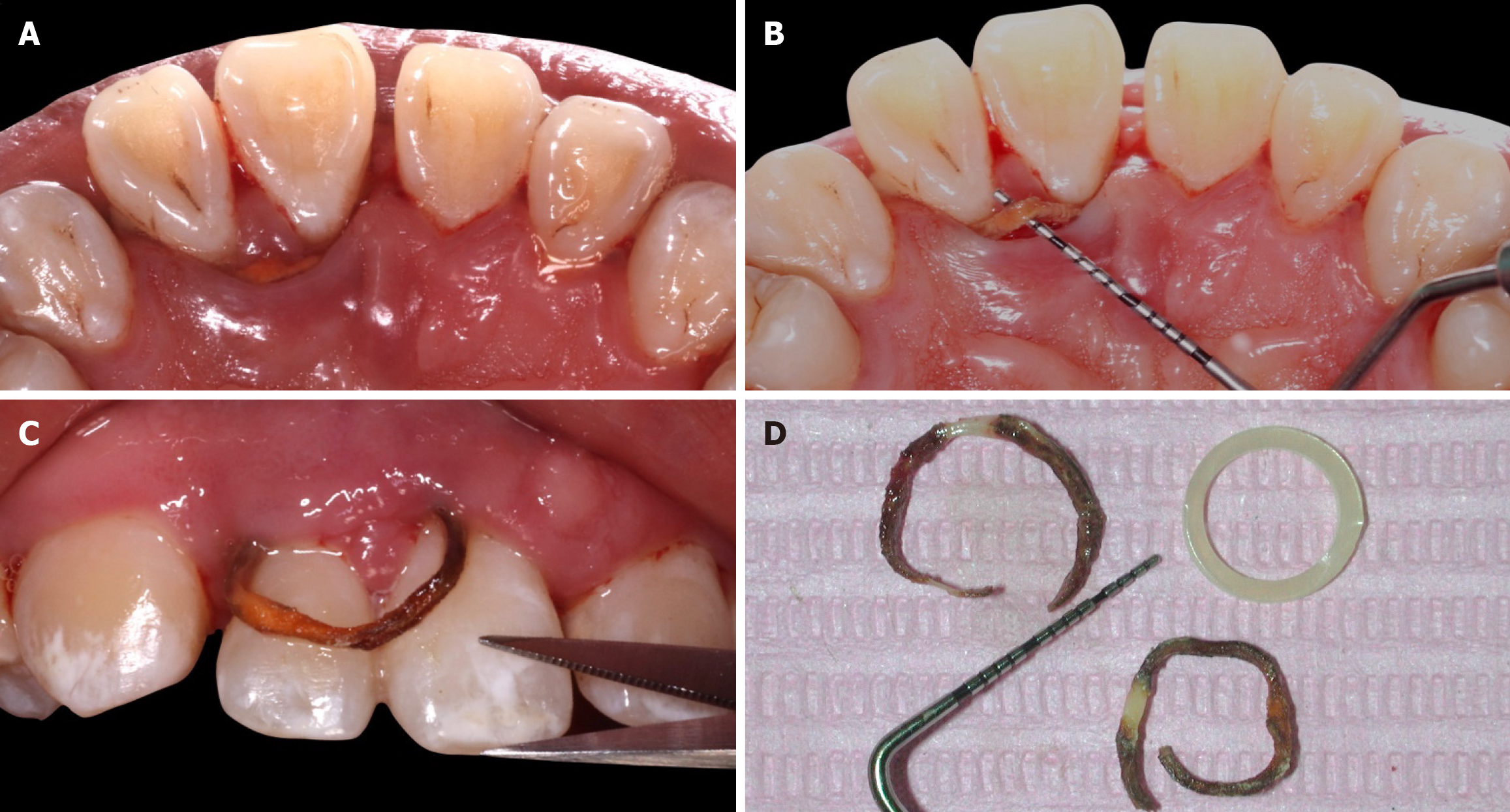

Hygienic phase I treatment included physiotherapy, coronal and subgingival debridement, and reevaluation. Subgingival debridement was manually performed via Gracey-type curettes and ultrasound. During this procedure, a foreign body was observed on the palatal surface of teeth 11 and 12, where a line in the gingival tissue had previously been identified (Figure 2A). This line was 1 mm and 2 mm thick and demonstrated an unknown length; moreover, it exhibited resistance to traction (Figure 2B). The foreign body was identified as an orthodontic elastic, which was subsequently cut to release and extract it (Figure 2C). Debridement was continued, and a second elastic was found; an image of the two removed elastics was captured and compared with a new orthodontic elastic (Figure 2D). Additionally, an occlusal adjustment was also performed to eliminate fremitus at teeth 11 and 12. Twelve weeks after subgingival debridement and the removal of both orthodontic elastics, a re-evaluation was conducted, in which PDs of 5 mm and 7 mm continued to be observed, with BP also observed at teeth 11 and 12.

Several months later, phase II surgery was scheduled for teeth 11 and 12, which consisted of the use of guided tissue regeneration (GTR) to address the bone defects. A splint was placed on teeth 13 to 23. The patient was asked to rinse his mouth for one minute with 0.12% chlorhexidine. Anesthesia was performed with 4% articaine hydrochloride plus 1:100000 epinephrine (Turbocaine, ZEYCO, Mexico), via infraorbital anesthesia techniques on the right and left sides of the mouth, as well as on the nasopalatine. Intrasurcular incisions were performed at teeth 14 to 23 (Figure 3A), and papilla-sparing incisions were performed on the palatal surface at 11, 12, 13, and 21 (Figure 3B) using a 15C scalpel blade (Ambiderm, Ribbel International Limited, New Delhi, India). A full-thickness buccal and palatal flap was elevated, thereby revealing the combined bony defects (Figures 3C and D), which were debrided with curettes. Bovine bone (NuOss, Ace Surgical, Brockton, United States) (Figure 3E) and a resorbable collagen membrane (RCM6, Collagen Matrix, New Jersey, United States) (Figure 3F) were placed. The patient was sutured with simple suspensory stitches (Figure 3G and H) using braided absorbable synthetic glycolic acid suture 40 and silk 50 (Surgeasy, Serral Laboratories, Mexico). Postoperative instructions included rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine twice daily for 15 days and administration of 875 mg of amoxicillin with 125 mg of clavulanic acid (one tablet every 12 hours for 8 days) and 25 mg of dexketoprofen (one tablet every 8 hours for 3 days). Postoperative care included the consumption of a soft, low-fat diet and ice-cold drinks, as well as reduced physical activity for one week. Spitting, smoking, and alcohol consumption were contraindicated. After fifteen days, the stitches were removed.

Phase III maintenance consisted of periodic visits at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months to evaluate and maintain oral hygiene. One year after surgery, a periodontal chart of the patient was created, with a PD of 1-3 mm, no BP, and low percentages of PoC being observed; moreover, these parameters are compatible with adequate periodontal health[12]. Figure 4 shows a comparison of initial images in the vestibular area with the presence of gingival inflammation (Figure 4A) and the presence of a cleft on the palate between the central and lateral sides (Figure 4B), as well as the presence of bone defects in the periapical radiograph (Figure 4C). At 6 months after surgery, the gingival tissues were observed to be deflated (Figure 4D and E), and the regenerated material was radiographically observed (Figure 4F). At two years after surgery, clinical images revealed stable PD, no bleeding on probing, reasonable hygiene control (Figure 4G and H), and radiographic stability in teeth 11 and 12 (Figure 4I).

Elastics are used in orthodontics on a daily basis. These materials can correct diastemas, malposed teeth, and crossbites. Many patients choose orthodontic rubber bands to close diastemas in order to reduce expenses[13]. However, dentists who use elastics should be knowledgeable of the potential for iatrogenic complications when they are misused[7,14-17].

The diagnosis of elastic dysfunction is challenging because the elastic band is not radiopaque, and the patient is often unaware of its loss[17]. The early diagnosis of this condition is essential for the effective and predictable management of such cases[18]. However, in the present report, it was not possible to determine how long the elastics had been immersed around the affected teeth; this patient´s elastics exhibited significant changes in color and texture compared with other reports, in which the elastics were estimated to have been immersed for 4-6 months[14,15,17]. Based on the patient´s dental medical history, the elastics may have been immersed for more than 4 years.

In this case, the observed damage was comparable to other instances in which supracrestal attachment tissue was significantly lost over a shorter period of time. However, these patients were between 8 years and 12 years of age[5,7,9,14,16], whereas the patient in the current report was 27-years-old. This finding leads to the question of whether the degree of damage is directly related to the time in which the elastic bands remain embedded in the periodontal tissues or whether other factors (such as the age of the individual or the development of the periodontium, as well as the eruption time of the affected organs) also influence the response to the foreign body.

As clinicians, the presence of foreign bodies in the supracrestal attachment tissues should be suspected when signs and symptoms such as pain, localized periodontal inflammation (including the presence of redness, swelling, and exudate), the rapid appearance of deep pockets, sensitivity to percussion, increased tooth mobility and extrusion are observed[14]. The peculiar clinical data of the present case included the presence of a horizontal line at the base of the interdental papilla extending toward the palatal surface between teeth 11 and 12, which was presumed to be a possible trace of the entry of the ligature. Moreover, when previous cases similar to the current case were reviewed, this line was also observed in the case reported by Xie et al[17].

The most relevant radiographic findings of the currently described condition include bone loss and/or discontinuity of the hard plate of the crest, as well as the extreme proximity of the apices[15], which we reported in the present case; correspondingly, these findings align with the results of previous case reports[19]. Thus, these findings can be considered to be helpful in the diagnosis. Similarly, resorption of the dental roots in teeth 11 and 12 was observed.

In the 2017 World Workshop Classification of periodontal and peri-implant diseases, interproximal bone loss is considered to be caused by local factors such as endo-perio lesions, root fractures, caries, restorations, or impacted teeth[20]. In the present case report, generalized gingivitis associated with dental plaque was diagnosed, along with periodontitis localized to teeth 11, 12, and 21, with these effects being related to local factors (orthodontic ligatures). Although elastic bands are not among the local factors described in the new classification system, previous studies in animal models and humans have demonstrated that a foreign body induces irreversible periodontal injury[3,4,21]. This effect occurs via ulceration of the sulcular epithelium and an acute inflammatory response that maintains osteoclastic activity, which is responsible for progressive bone loss and the physical pressure generated by the foreign body[19,21].

The periodontal grading system is utilized as an indicator of the rate of periodontitis progression. The criteria for this system are classified into direct or indirect evidence of the estimation of progression. Direct evidence is based on longitudinal observations of CAL and radiographic bone loss[22]. In the present case, at the time of diagnosis, longitudinal data were not available; therefore, indirect evidence was used, whereby the tooth with the most significant bone loss was radiographically identified, and the percentage of radiographic bone loss divided by the patient's age was measured, thereby yielding a result > 1.0. Thus, the progression was classified as being grade C. However, via direct evidence, this indicator can be modified. After 2 years of follow-up, the assessment at the attachment level and the radiographic bone level continued to demonstrate no losses; after 5 years of follow-up, more data on these parameters will be available.

Regarding the management of sites that have been affected by the iatrogenic use of elastic bands, two scenarios have been observed in clinical case reports. Bands that have been invaginated as interdental separators (with some cases only involving the removal of the foreign body and debridement of the site) achieved reestablishment[23]; conversely Nettem et al[24] reported a similar situation in which the flap was elevated, the foreign body was removed, and debridement was performed, thereby resulting in the reestablishment of the lost bone. However, in other reports, flap elevation, debridement of both the granulomatous tissue and the foreign body, and GTR procedures were performed[14,16]. The bands that were invaginated around one or several of the teeth demonstrated significantly higher potential for damage; thus, the management for these types of bands is usually more complex and has a greater probability of resulting in tooth loss. Some reports have demonstrated promising results via the removal of the ligatures, debridement, and GTR, as were performed in the present case, as well as in a previous study by Xie et al[17]. These results were in contrast to the findings of the report by Pepelassi and Tsarouchi[19], in which intrabony defects in the central and lateral upper teeth that were generated by a ligature were surgically addressed and debrided; however, no regenerative material was used, thereby resulting in unfavorable gingival recessions. However, although other researchers in other cases have opened and debrided defects, along with removing the ligatures and utilizing some regenerative material, they did not maintain the teeth[7,9].

Several procedures demonstrating variable results have been reported, and there is no consensus regarding the best management protocol; moreover, decision-making depends on the severity of the case. In this case, both elastics were removed during nonsurgical periodontal therapy. The healing period allowed for a re-evaluation to occur, where improved gingival inflammation was observed. However, the probing depth remained > 5 mm, with BP; thus, a surgical phase with GTR was performed, thereby allowing for partial restoration of the lost bone support.

In previous years, various classical animal studies have demonstrated the potential of cells from the periodontal ligament to form new attachments[25,26], thus allowing for GTR to be possible. The present report demonstrates results from 2-year follow-up with clinical and radiographic stability in managing intrabony defects associated with the iatrogenic use of elastic bands treated with GTR. However, the risk of manifestation of ankylosis or root resorption has also been reported in previous studies as being late-stage complications of GTR[27-29]. Therefore, the patient from the current case report is in a periodontal maintenance phase, with periodic visits being conducted every 6 months to maintain the general oral health status and to perform long-term clinical and radiographic monitoring at sites with GTR on an annual basis.

The use of elastic bands of various sizes and elasticities is often essential in multiple orthodontic treatments. However, it is crucial to perform a thorough check-up for each patient during treatment and at the end of treatment to remove any remaining residue of resin, metal bands, or orthodontic bands, as well as to inform patients of the importance of attending their follow-up appointments.

Symptoms such as pain, localized periodontal inflammation, the rapid appearance of deep pockets, sensitivity to percussion, increased tooth mobility and extrusion, radiographic bone loss, and root proximity are essential data that clinicians should consider in order to avoid the iatrogenic use of elastics.

The use of elastic bands in orthodontics requires special care; moreover, GTR is a management option for intrabony defects associated with the iatrogenic use of bands.

Our most sincere thanks to Cecilia Padilla Felix for her support and help during the years of work on this case.

| 1. | Rafiuddin S, Yg PK, Biswas S, Prabhu SS, Bm C, Mp R. Iatrogenic Damage to the Periodontium Caused by Orthodontic Treatment Procedures: An Overview. Open Dent J. 2015;9:228-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carroll LFB, Snider FF. Tooth Extraction in Hemophilia**The dental work was done by F. F. S. in his private office; the clinical investigations were made by C. L. B. at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, Departments of Medicine and Orthopedics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1939;26:1933-1942. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dalitsch WW. Dental Extraction in Hemophilia**Read at the Eighteenth Annual Clinical Session of the American College of Physicians, Chicago, Ill., April 19, 1934. J Am Dent Assoc. 1934;21:1804-1811. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Regev E, Lustmann J, Nashef R. Atraumatic teeth extraction in bisphosphonate-treated patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1157-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bergantin BTP, Rios D, Oliveira DSB, Júnior ESP, Hanemann JAC, Honório HM. Localized Bone Loss Resulted from an Unlikely Cause in an 11-Year-Old Child. Case Rep Dent. 2018;2018:3484513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Finkbeiner RL, Nelson LS, Killebrew J. Accidental orthodontic elastic band-induced periodontitis: orthodontic and laser treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1565-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Konstantonis D, Brenner R, Karamolegkou M, Vasileiou D. Torturous path of an elastic gap band: Interdisciplinary approach to orthodontic treatment for a young patient who lost both maxillary central incisors after do-it-yourself treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:835-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dianiskova S, Calzolari C, Migliorati M, Silvestrini-Biavati A, Isola G, Savoldi F, Dalessandri D, Paganelli C. Tooth loss caused by displaced elastic during simple preprosthetic orthodontic treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4:285-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Alves MG, Kitakawa D, Becker JB, Brandão AA, Cabral LA, Almeida JD. Elastic band causing exfoliation of the upper permanent central incisors. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:186945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vishwanath A, Sharmada B, S Pai S, Nelvigi N. Severe Bone Loss induced by Orthodontic Elastic Separator: A Rare Case Report. JIOS. 2013;47:97-99. |

| 11. | International Organization for Standardization. ISO 3950:2016. 2016. Available from: https://www.iso.org/standard/68292.html. |

| 12. | Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, Bartold PM, Dommisch H, Eickholz P, Geisinger ML, Genco RJ, Glogauer M, Goldstein M, Griffin TJ, Holmstrup P, Johnson GK, Kapila Y, Lang NP, Meyle J, Murakami S, Plemons J, Romito GA, Shapira L, Tatakis DN, Teughels W, Trombelli L, Walter C, Wimmer G, Xenoudi P, Yoshie H. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89 Suppl 1:S74-S84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 533] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 58.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adcock JE. Exfoliation of maxillary central incisors due to misapplication of orthodontic rubber bands. Tex Dent J. 1999;116:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Al-Qutub MN. Orthodontic elastic band-induced periodontitis - A case report. Saudi Dent J. 2012;24:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moghaddas H, Pezeshkfar A. Severe Gingival Recession Caused by Orthodontic Rubber Band: A Case Report. J Periodontol Implant Dent. 2010;2:83-87. |

| 16. | Zager NI, Barnett ML. Severe bone loss in a child initiated by multiple orthodontic rubber bands: case report. J Periodontol. 1974;45:701-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xie C, Liu X, Mei J, Liu Y, Yu H. Periodontal repair for advanced bone loss caused by orthodontic elastic bands: A case report with 7-year follow-up and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e7061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tandon S, Ahad A, Kaur A, Faraz F, Chaudhary Z. Orthodontic elastic embedded in gingiva for 7 years. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:212106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pepelassi EE, Tsarouchi D. Severe periodontal destruction caused by orthodontic elastic bands: A case report and review of the literature. Dent Oral Craniofac Res. 2019;5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Tonetti MS, Sanz M. Implementation of the new classification of periodontal diseases: Decision-making algorithms for clinical practice and education. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46:398-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Caton JG, Zander HA. Primate model for testing periodontal treatment procedures: I. Histologic investigation of localized periodontal pockets produced by orthodontic elastics. J Periodontol. 1975;46:71-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89 Suppl 1:S159-S172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 1446] [Article Influence: 206.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Becker T, Neronov A. Orthodontic elastic separator-induced periodontal abscess: a case report. Case Rep Dent. 2012;2012:463903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nettem S, Kumar Nettemu S, Kumar K, Reddy V, Siva Kumar P. Spontaneous Reversibility of an Iatrogenic Orthodontic Elastic Band-induced Localized Periodontitis Following Surgical Intervention - Case Report. Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19:77-80. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Melcher AH. On the repair potential of periodontal tissues. J Periodontol. 1976;47:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Karring T, Isidor F, Nyman S, Lindhe J. New attachment formation on teeth with a reduced but healthy periodontal ligament. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Björn H, Hollender L, Lindhe J. Tissue regeneration in patients with periodontal disease. Odontol Revy. 1965;16:317-326. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Karring T, Nyman S, Lindhe J, Sirirat M. Potentials for root resorption during periodontal wound healing. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:41-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Karring T, Nyman S, Lindhe J. Healing following implantation of periodontitis affected roots into bone tissue. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:96-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/