Published online Jul 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i20.102695

Revised: February 24, 2025

Accepted: March 13, 2025

Published online: July 16, 2025

Processing time: 165 Days and 17.2 Hours

Recurrence of common bile duct (CBD) calculi within 30 days following T-tube cholangiography is exceedingly rare.

This article details an instance of choledocholithiasis involving a 1.2 cm × 0.9 cm stone located in the lower and middle segments of the CBD, identified 30 days after T-tube cholangiography, accompanied by multiple microstones. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed dilation of both intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, with the widest segment of the CBD measuring appro

Although recurrence of choledocholithiasis within such a short postoperative period is exceedingly uncommon, this case underscores the necessity for clinicians to remain vigilant regarding the potential for early postoperative recurrence.

Core Tip: Thirty days subsequent to undergoing T-tube cholangiography following common bile duct (CBD) exploration and cholecystectomy, a patient was diagnosed with recurrent CBD stones by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Despite the rarity of CBD stone recurrence within such a brief postoperative interval, this case underscores the imperative for clinicians to remain highly vigilant concerning the potential for early postoperative recurrence.

- Citation: Ren ZH, Gao YY, Lu Q, Yao YM, Wan Y. Rare recurrence of common bile duct calculi post T-tube cholangiography: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(20): 102695

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i20/102695.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i20.102695

Gallstone disease frequently requires surgical treatment, with about 35% of patients experiencing symptoms that lead to a cholecystectomy[1]. Among the cholecystectomies performed annually for cholelithiasis, the incidence of common bile duct (CBD) stones ranges from 5% to 15%[2]. Obstructive stones in the CBD can originate from the CBD, the gallbladder, or ducts either outside or inside the liver. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of choledocholithiasis[3]. The presence of CBD stones poses significant concerns due to the potential development of complications such as obstructive jaundice, biliary pancreatitis or acute cholangitis if left untreated, which can result in adverse morbidity or even mortality[4]. The recurrence rate of CBD stones following stone extraction is reported to be between 4% and 24%[5]. The mean time to recurrence of CBD stones is 19.7 months, with a range of 5-72 months[6]. Currently, the optimal treatment for choledocholithiasis remains a subject of debate. The two most widely accepted techniques are endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) combined with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and laparoscopic CBD exploration (LCBDE)[7].

A 72-year-old man was readmitted to the Department of Geriatric Surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China, because of recurrent choledocholithiasis, occurring 5 days after choledocholithotomy performed 2 months prior.

Two months prior, the patient had undergone laparoscopic choledochotomy combined with LC for treatment of gallbladder stones and choledocholithiasis.

He had a 15-year history of hypertension, with recorded maximum blood pressure levels reaching 29.3/13.3 kPa, and had previously undergone appendectomy at a local hospital.

There is no record of related diseases in the family, and no history of infectious and genetic diseases.

Clinical examination revealed pressure-induced pain in the right upper abdomen.

Routine hematological and biochemical investigations, including hemoglobin levels, total white blood cell count, and liver function tests, indicated serum total bilirubin concentration of 31.4 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase level of 19 U/L and alanine aminotransferase level of 16 U/L. Renal function tests, serum electrolytes, serum glucose, and urinalysis results were within normal limits (Table 1).

| Date | At admission | At discharge | Lab reference values |

| Hemoglobin | 136 | 133 | 130-175 g/L |

| WBC | 7.34 | 13.45 | 3.5-9.5 × 1012/L |

| Platelets | 215 | 224 | 125-350 × 109/L |

| PT/INR | 13.1/1.02 | - | 11-14/0.94-1.30 |

| TBIL | 31.4 | 56.5 | 3.4-17.1 μmol/L |

| DBIL | 10.6 | 19.1 | 0-3.4 μmol/L |

| IBIL | 20.8 | 37.4 | 0-17.1 μmol/L |

| ALT | 16 | 20 | 9-50 U/L |

| AST | 19 | 16 | 15-40 U/L |

| ALP | 170 | 140 | 45-125 U/L |

| GGT | 153 | 114 | 10-60 U/L |

| Total protein | 67.7 | 67.2 | 65-85 g/L |

| Albumin | 34.2 | 36.6 | 40.0-55.0 g/L |

| Globulin | 33.5 | 30.6 | 20.0-40.0 g/L |

| Urea/creatinine | 57/3.39 | 55/3.49 | 57-111/3.60-9.50 |

| Sodium/potassium | 141.4/4.17 | 136.9/2.88 | 135-145/3.5-5.5 |

| anti-HIV/anti-HbsAg/anti-HCV | Non-reactive | - | - |

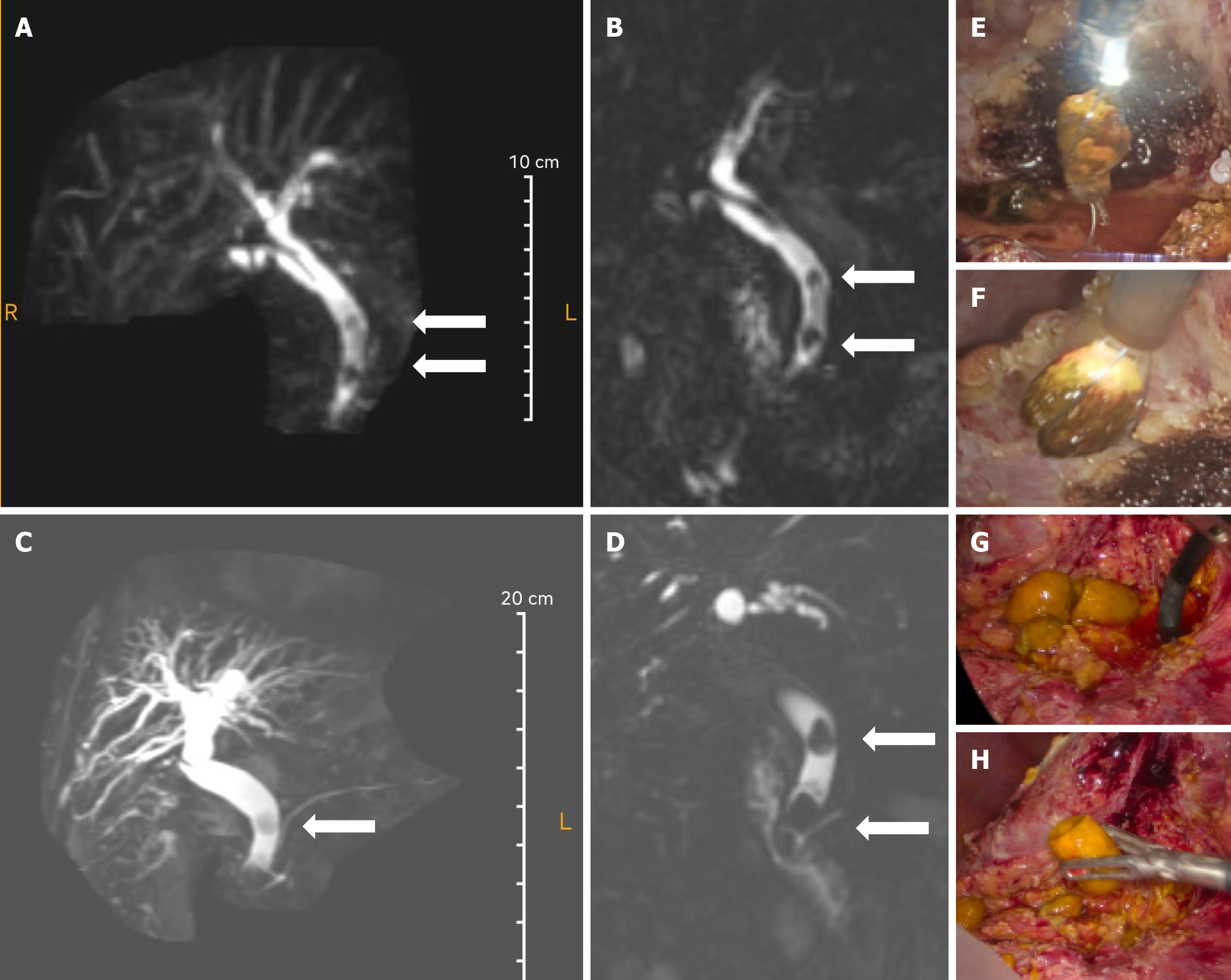

T-tube cholangiography conducted 30 days postoperatively indicated that the bile ducts were patent with no evidence of filling defects (Figure 1), leading to subsequent removal of the T-tube. Preoperative MRCP for initial LCBDE + LC revealed a mildly dilated CBD, right and left hepatic ducts, common hepatic duct, and intrahepatic bile ducts. The CBD exhibited nodular filling defects measuring 0.6-0.7 cm in diameter and demonstrated hypodensity on T2-weighted imaging (Figure 2A and B). High-density calculi were also observed within the dilated CBD. Preoperative MRCP for subsequent LCBDE did not visualize the gallbladder. The maximum diameter of the CBD measured approximately 2.0 cm, with multiple rounded low-signal shadows identified in the middle and lower segments of the duct, the largest of which measured approximately 1.2 cm × 0.9 cm (Figure 2C and D).

Recurrent choledocholithiasis.

The patient signed informed consent for surgery and was scheduled for elective surgery. Intraoperatively, extensive adhesions were observed in the epigastric region. The gallbladder was absent, and significant dilation of the extrahepatic bile ducts was noted. The middle portion of the CBD measured approximately 1.2 cm in diameter and exhibited normal alignment. No anomalies were detected in the stomach, spleen, small intestine, colon or mesentery. Subsequently, meticulous dissection of the hepatic hilum was performed. The anterior and superior segments of the CBDs were liberated utilizing suction, followed by incision with electrocautery. A choledochoscope was introduced to investigate the thickening of the choledochal wall and mucosal roughness, revealing multiple stones within the CBD. These stones were individually extracted using a stone extraction basket, and any residual fragments were flushed out with saline. The CBD was transected using an ultrasonic knife, and the distal end was closed with interrupted sutures using Prolene 4-0 barbed wire. The proximal end of the CBD was mobilized and prepared for choledochojejunal anastomosis. The distal jejunum was elevated approximately 25 cm from the ligament of Treitz, and a longitudinal incision of approximately 1.0 cm was made along the antimesenteric border of the intestinal lumen. The jejunum and the transected end of the choledochal duct were approximated using interrupted sutures with 4-0 barbed wire on both the anterior and posterior walls. Upon completion of the suturing, the anastomosis was assessed for bile leakage, which was found to be minimal, indicating a tension-free closure. Approximately 60 cm distal to the biliary-intestinal anastomosis, a side-to-side anastomosis was performed between the proximal and distal jejunum using a linear cutting closure device along the mesenteric border. The common opening was subsequently closed with 4-0 barbed suture. Post-suturing, the anastomosis was evaluated for patency, absence of tension, and adequate intestinal blood flow, confirming successful completion of the procedure. Additionally, the proximal jejunum was transected using a linear cutting closure device approximately 5 cm from the biliary anastomosis. Following verification of the absence of active bleeding, a drain was positioned at the site of the biliary anastomosis and exteriorized through the abdominal wall. The abdominal closure was performed in a layered manner. Figure 2E-H illustrates intraoperative images documenting extraction of a stone from the bile duct. Serum total cholesterol levels exhibited a progressive decline. Prior to the initial surgical intervention, the total cholesterol level was 2.3 mmol/L. Following initial surgery, it decreased to 2.13 mmol/L, and after the second operation, it further declined to 2.07 mmol/L. This ongoing reduction in cholesterol levels suggested that the CBD stones were primarily composed of cholesterol. The formation of cholesterol stones is closely associated with cholesterol supersaturation in bile, and the gradual decrease in cholesterol levels postoperatively may reflect improvement in bile composition and a reduction in stone burden. This alteration not only corroborates the diagnosis of cholesterol stones but also serves as a significant biochemical index for postoperative monitoring. These surgical images confirm the presence of multiple stones, consistent with the obstruction observed in the MRCP scan.

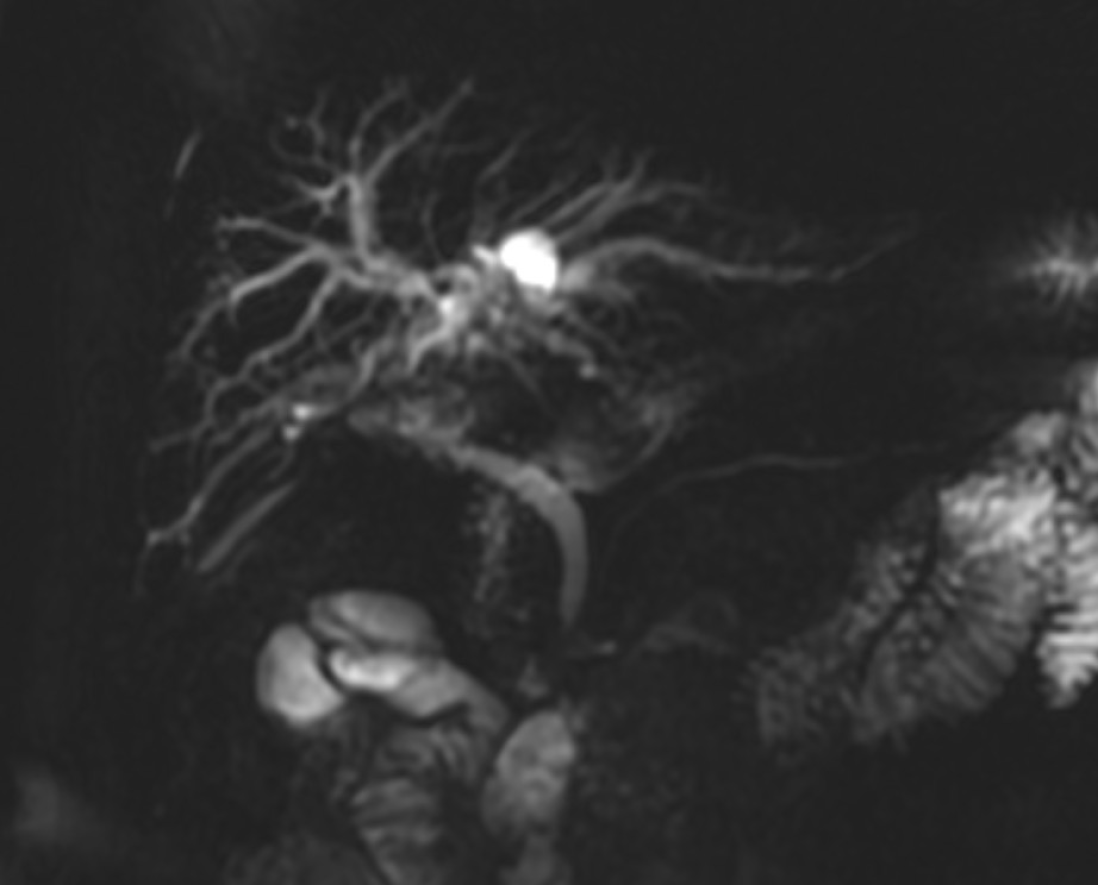

Following the surgical procedure, the patient initially demonstrated satisfactory recovery. However, 2 months postoperatively, the patient presented with symptoms indicative of bile duct inflammation; notably, recurrence of right upper abdominal pain. MRCP examination revealed no significant presence of calculi (Figure 3). The patient underwent symptomatic management, which included administration of anti-infective agents, anti-inflammatory cholagogue, and laxatives aimed at alleviating intestinal pressure. This therapeutic approach resulted in the patient's recovery, leading to discharge from hospital. The patient expressed satisfaction with the treatment received.

Data indicate that the prevalence of CBD stones in patients presenting with symptomatic gallstones is between 10% and 20%[8,9]. Recurrence of bile duct stones has been reported in 3.7%-24% of patients, even following the complete removal of the stones[6,10-13]. ERCP is usually the main treatment for CBD stones. However, different techniques including percutaneous and transhepatic stone removal, open CBD exploration, and laparoscopic approaches are also applied. Notably, LCBDE offers advantages in terms of fewer complications and reduced treatment costs compared to ERCP, suggesting its potential for broader clinical application[14]. In a study involving 458 patients with an average long-term follow-up of 6.8 years after choledocholithiasis surgery, approximately 3.9% experienced recurrence within the first 2 years, with most recurrences occurring beyond this period. The minimum duration for recurrence of choledocholithiasis postoperatively has yet to be documented. The incidence of recurrent choledocholithiasis within 30 days following T-tube angiography is exceedingly rare[15]. MRCP serves as a noninvasive modality capable of detecting choledocholithiasis in the preoperative setting[3]. Factors such as age, choledochal diameter, genetic predisposition, and other variables may contribute to the recurrence of choledochal stones[16]. Postoperative strategies to mitigate the risk of CBD stone recurrence include adherence to a healthy diet, regular exercise, and administration of ursodeoxycholic acid[17].

This case report presents an instance of recurrent choledocholithiasis occurring within 30 days following T-tube cholangiography, characterized by a stone measuring 1.2 cm × 0.9 cm situated in the lower and middle segments of the choledochotomy, accompanied by multiple microstones. Although the recurrence of choledocholithiasis within such a short postoperative period is exceedingly uncommon, this case underscores the necessity for clinicians to remain vigilant regarding the potential for early postoperative recurrence. This is particularly pertinent for patients at elevated risk, such as those exhibiting bile duct dilatation (CBD diameter ≥ 2 cm) or the presence of microscopic stone remnants.

| 1. | V V, S Kumar N, Khan O, Azharuddin SK. Giant Choledocholithiasis With Choledochal Cyst: A Report of a Rare Case. Cureus. 2024;16:e64306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cianci P, Restini E. Management of cholelithiasis with choledocholithiasis: Endoscopic and surgical approaches. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:4536-4554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (21)] |

| 3. | Chen W, Mo JJ, Lin L, Li CQ, Zhang JF. Diagnostic value of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in choledocholithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3351-3360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Oh DJ, Nam JH, Jang DK, Lee JK. Complications of common bile duct stones: A risk factors analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2021;20:361-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wen N, Wang Y, Cai Y, Nie G, Yang S, Wang S, Xiong X, Li B, Lu J, Cheng N. Risk factors for recurrent common bile duct stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;17:937-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lai KH, Lo GH, Lin CK, Hsu PI, Chan HH, Cheng JS, Wang EM. Do patients with recurrent choledocholithiasis after endoscopic sphincterotomy benefit from regular follow-up? Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:523-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhu J, Tu S, Yang Z, Fu X, Li Y, Xiao W. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for elderly patients with choledocholithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:1522-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee J, Jeong HJ, Kim H, Park JS. The Role of the Bile Microbiome in Common Bile Duct Stone Development. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Williams E, Beckingham I, El Sayed G, Gurusamy K, Sturgess R, Webster G, Young T. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2017;66: 765-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bergman JJ, van der Mey S, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Gouma DJ, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Long-term follow-up after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones in patients younger than 60 years of age. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Altman C, Liguory C, Etienne JP. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hawes RH, Cotton PB, Vallon AG. Follow-up 6 to 11 years after duodenoscopic sphincterotomy for stones in patients with prior cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1008-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saito M, Tsuyuguchi T, Yamaguchi T, Ishihara T, Saisho H. Long-term outcome of endoscopic papillotomy for choledocholithiasis with cholecystolithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:540-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zou Q, Ding Y, Li CS, Yang XP. A randomized controlled trial of emergency LCBDE + LC and ERCP + LC in the treatment of choledocholithiasis with acute cholangitis. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2022;17:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Costamagna G, Tringali A, Shah SK, Mutignani M, Zuccalà G, Perri V. Long-term follow-up of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis, and risk factors for recurrence. Endoscopy. 2002;34:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Velamazán R, López-Guillén P, Martínez-Domínguez SJ, Abad Baroja D, Oyón D, Arnau A, Ruiz-Belmonte LM, Tejedor-Tejada J, Zapater R, Martín-Vicente N, Fernández-Esparcia PJ, Julián Gomara AB, Sastre Lozano V, Manzanares García JJ, Chivato Martín-Falquina I, Andrés Pascual L, Torres Monclus N, Zaragoza Velasco N, Rojo E, Lapeña-Muñoz B, Flores V, Díaz Gómez A, Cañamares-Orbís P, Vinzo Abizanda I, Marcos Carrasco N, Pardo Grau L, García-Rayado G, Millastre Bocos J, Garcia Garcia de Paredes A, Vaamonde Lorenzo M, Izagirre Arostegi A, Lozada-Hernández EE, Velarde-Ruiz Velasco JA, de-Madaria E. Symptomatic gallstone disease: Recurrence patterns and risk factors for relapse after first admission, the RELAPSTONE study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:286-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gutt C, Schläfer S, Lammert F. The Treatment of Gallstone Disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:148-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/