Published online Jul 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i19.103946

Revised: January 28, 2025

Accepted: February 19, 2025

Published online: July 6, 2025

Processing time: 104 Days and 15.7 Hours

Cervical cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the most common cancer in females living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Cervical cancer is classified as an acquired immune deficiency syndrome-defining disease. Brain metastases (BMs) from cervical cancer are extremely rare, with an incidence rate of approximately 0.63%, and there is limited information on opti

A 42-year-old Chinese female with HIV infection was diagnosed with stage IIIC1r cervical cancer in March 2022 based on the International Federation of Gyne

Females living with HIV are more than three times more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer. Due to the scarcity of cervical cancer BMs, therapeutic protocol experience is limited. In addition to the existence of the blood-brain barrier, the treatment of cervical cancer BMs appears to be exceptionally complex, and a multi-modal treatment approach consisting of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation may help prolong patients’ life. For females living with HIV, antiretroviral therapy should be prioritized, as recommended by the Center for Disease Control in China. An intact immune system and a high CD4+ count are positive indicators of treatment response and tumor reduction. The overall survival of patients with cervical cancer after brain metastasis is approximately 3-5 months. However, owing to multimodal therapy and the use of antiretroviral therapy, the patient reported in this case showed no signs of recurrence after prolonged follow-up.

Core Tip: A 42-year-old Chinese female patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection, was diagnosed with stage IIIC1r cervical cancer based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Fourteen months after concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the tumor metastasized to the brain. The patient underwent a craniotomy and radiotherapy for postoperative metastatic lesions. Metastasis of cervical cancer to the brain is relatively rare, and the treatment of cervical cancer brain metastases is complicated. A multimodal treatment approach consisting of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy may need to be considered to prolong such patients’ life. Additionally, antiretroviral therapy should be implemented for females living with human immunodeficiency virus.

- Citation: Huang HQ, Gong FM, Sun CT, Xuan Y, Li L. Brain and scalp metastasis of cervical cancer in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(19): 103946

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i19/103946.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i19.103946

Cervical cancer is the fourth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among females worldwide, with a global incidence of approximately 570000 new cases and 311000 deaths in 2018[1]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main causative agent of cervical cancer, causing 99.7% of all cervical cancer cases, with high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 accounting for 75%[2]. In 2020, an estimated 37.7 million people globally (uncertainty range 30.2-45.1 million) will be infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[3]. Among HIV-infected women, cervical cancer is the most commonly detected malignancy and is classified as an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining disease. Persistent HPV infection is closely associated with advanced HIV infection, which is featured by a weakened immune system due to a reduction in the number of CD4+ T-helper lymphocytes, a hallmark of AIDS progression[4].

Cervical cancer metastatic lesions in the brain are relatively rare, but the risk of brain metastasis is increased in patient with AIDS due to immune deficiency, with reports suggesting a more aggressive form of cervical cancer with advanced stages and more susceptible to distant metastases in patients with HIV associated immunosuppression[5,6]. In this paper, we report a case of cervical cancer complicated by AIDS and eventually developing into scalp metastasis. Additionally, we discuss the characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of cervical cancer in patients with AIDS.

A 42-year-old Chinese female patients with HIV infection was diagnosed with stage IIIC1r cervical cancer based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics system in March 2022.

The patient’s clinical symptoms included unusual vaginal bleeding persisting for six months prior to hospital admission.

The patient was diagnosed with AIDS in 2014 and has since been on antiretroviral therapy (ART) under the care of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control, and was tested for CD4+ cell levels regularly for adjustment of ART regimens.

The patient declared no significant personal or family medical history.

Gynecological examination revealed a cervical enlargement of approximately 4.5 cm in diameter, with infiltration into the parametria, but not extending to the pelvic wall or involving the vagina.

HPV tests were positive for HPV 16 and HPV 18. Histopathology of a cervical biopsy indicated poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

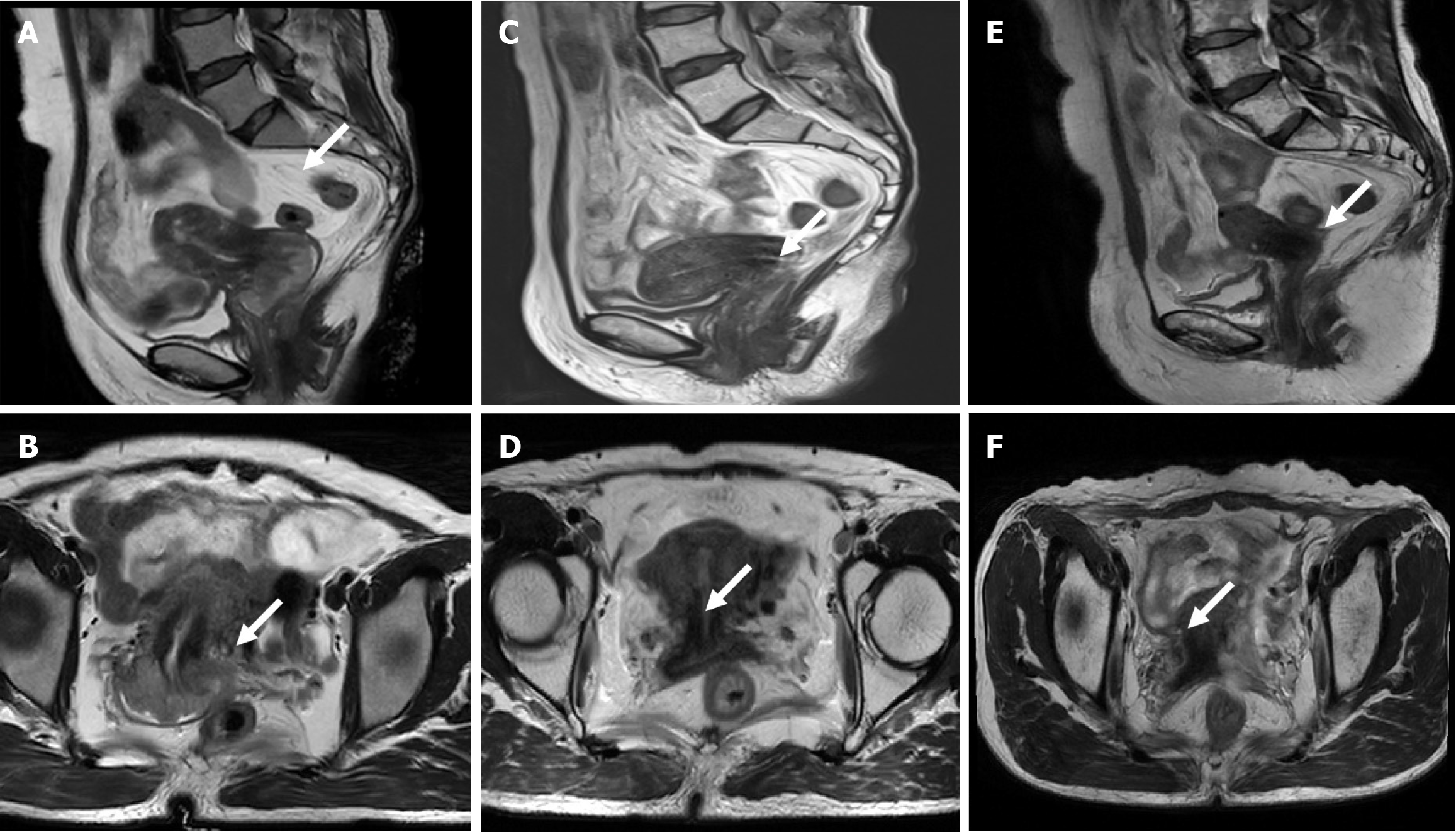

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cervical mass with a segmental absence of cervical stroma, a lesion protruding downward into the vaginal vault, and indistinct boundaries from the anterior rectal wall. The bilateral obturator lymph nodes were also enlarged (Figure 1).

Following the revised 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system, the patient was diagnosed with stage IIIC1r cervical cancer, considering the pelvic lymph node metastasis.

The patient underwent radical concurrent chemoradiotherapy based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. External pelvic radiotherapy was delivered at a dose of 45 Gy divided into 25 fractions (1.8 Gy) over the whole pelvis and 55 Gy for the lymph nodes which was divided into 25 fractions of 2.2 Gy, using the intensity-modulated radiation therapy technique. Concurrently, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, the patient received weekly cisplatin chemotherapy at a dose of 40 mg/m2. Additionally, a high-dose rate of intravaginal irradiation using an iridium (Ir192) of 30 Gy divided into 5 fractions was also administered. The patient tolerated the treatment well, experiencing only moderate nausea and vomiting, and grade 3 myelosuppression according to the scale of the Ration Therapy Oncology Group. Subsequent follow-ups were conducted every 3 months. Pelvic MRI revealed good local control of the tumor (Figure 1) and no complaints of discomfort during the follow-up period were reported. The patient was still on ART under the care of the Chinese Centre for Disease Control.

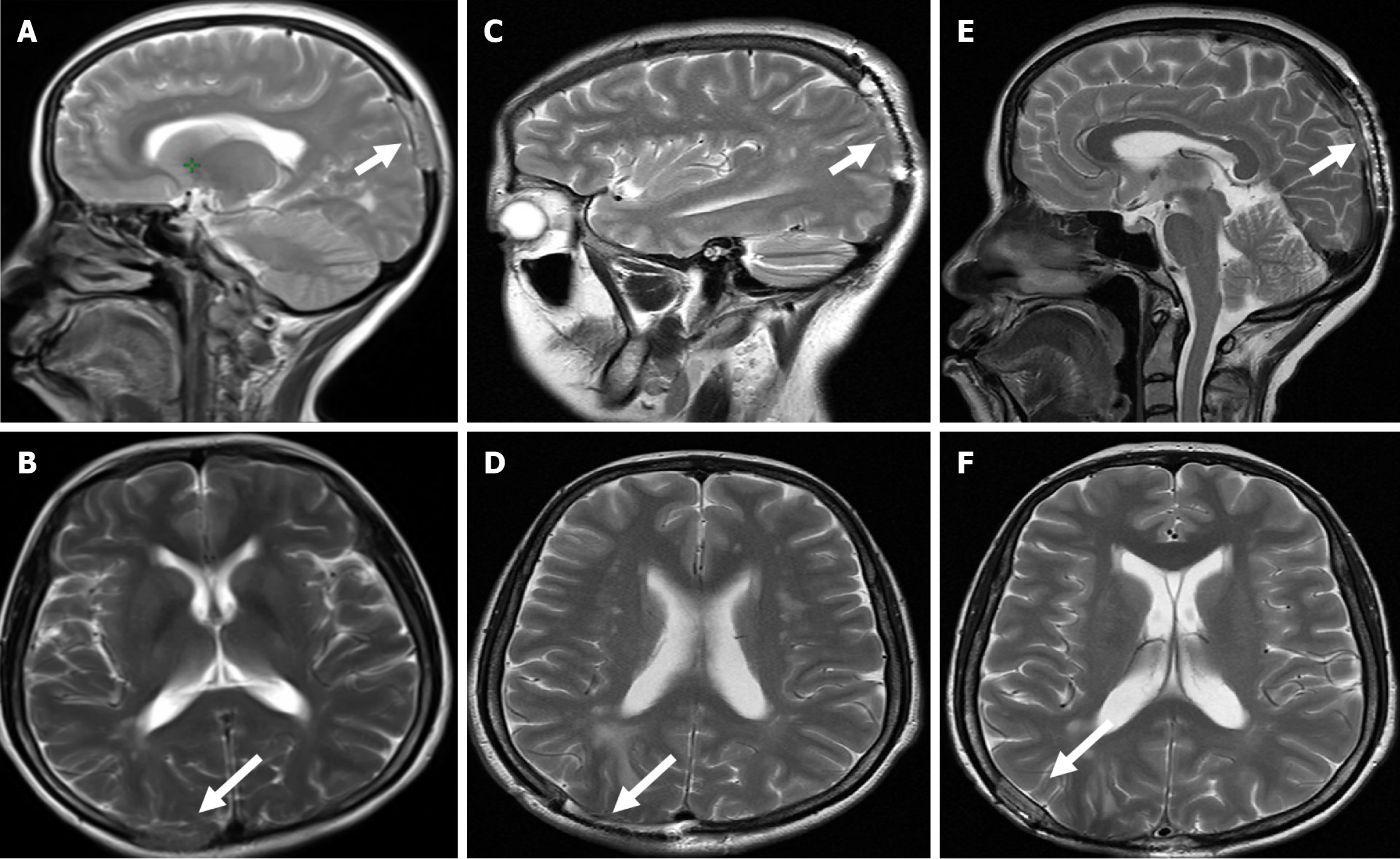

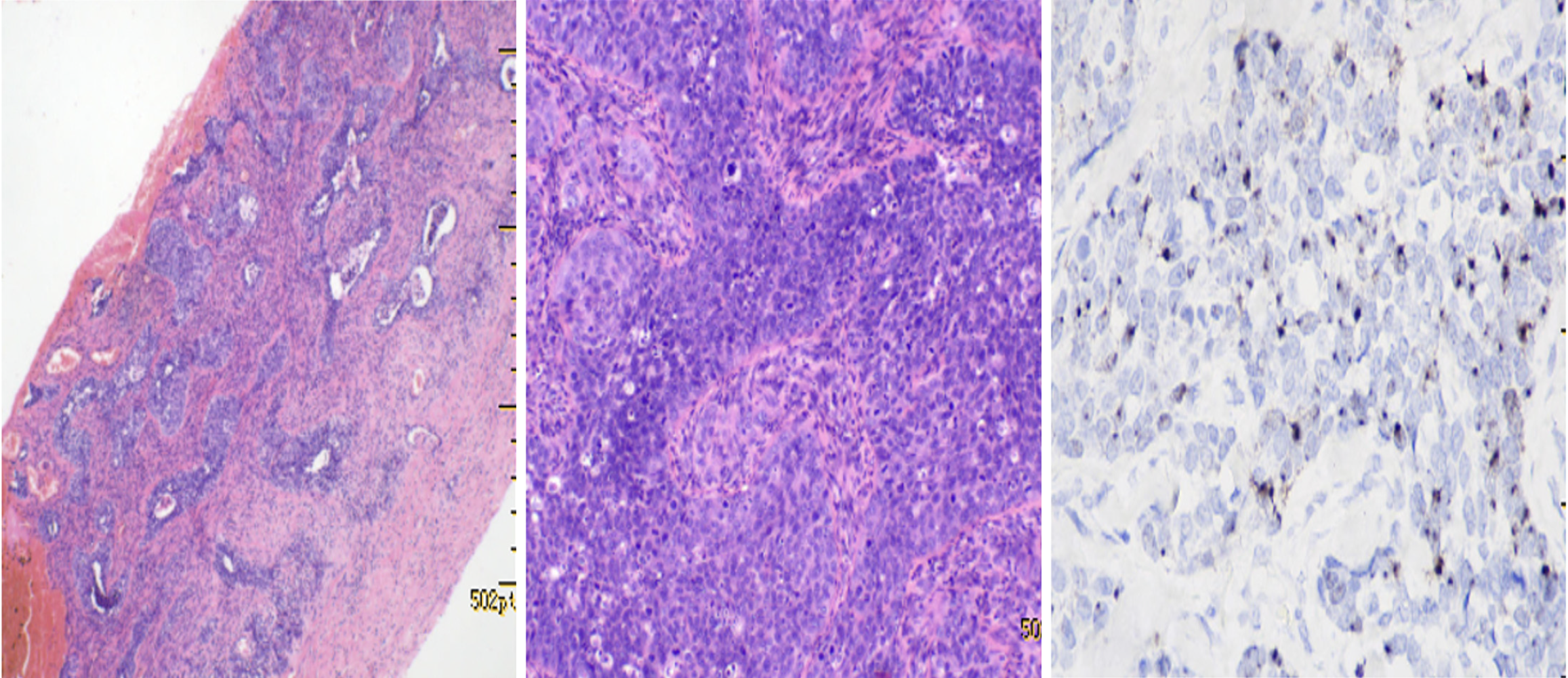

However, 14 months after the initial treatment by January 2024, the patient presented with symptoms of explosive headache for 2 days and was admitted for emergency treatment at a local hospital. An MRI scan of the brain revealed a solitary lesion measuring 3.1 cm × 0.9 cm on the right side of the head between the right parietal skull and dura mater, accompanied by edema of the surrounding soft tissues (Figure 2). The patient underwent tumor resection surgery of the affected area on February 1, 2024. Postoperative pathological examination indicated cervical squamous cell carcinoma metastasis, which was consistent with the patient’s medical history (Figure 3). Postoperatively, the patient received external radiotherapy for the metastatic lesions, at a dose of 45 Gy divided into 25 fractions of 1.8 Gy from March 1, 2024 to April 10, 2024. Due to the patient’s deteriorating physical condition and economic constraints, she decisively declined further chemotherapy and any other additional treatment strategies suggested. The patient remained under clinical follow-up for 7 months, with no signs of relapse.

Cervical cancer is a major global health and financial concern, and has one of the world’s highest annual incidence rates and a poor prognosis. Buoyed by growing global optimism about the possibility of reducing cervical cancer worldwide, the World Health Organization’s Cervical Cancer Elimination Strategy has set ambitious targets for all countries to achieve the following by 2030: 90% of girls fully vaccinated against HPV before the age of 15, 70% of women screened by the age of 35 and again by the age of 45, and 90% of women with detected precancerous lesions treated (“90-70-90”)[7].

Over the past four decades, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has become, and will continue to be, one of the world’s most serious public health, development, and economic challenges. In 2020, an estimated 37.7 million people (uncertain range 30.2-45.1 million) were living with HIV, of whom 53% were young and adult women[8]. Females living with HIV are more than three times more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer[9]. Persistent infection with HPV is associated with advanced HIV infection, which is characterized by a weakened immune system due to low CD4+ T-helper lymphocyte counts—a hallmark of AIDS[4].

Approximately 16% of cervical cancer cases metastasize to distant sites[10], and despite the high rate of invasion, brain metastases (BMs) are relatively rare, estimated at 0.63%[11]. In recent years, the incidence of cervical cancer with BMs has increased. This has been attributed to improved treatment of the primary cancer, which has led to prolonged survival periods[12]. The risk of brain metastasis increases when tumors are poorly differentiated or concomitant with other conditions, such as immune deficiency, as seen with the patient in the present case who had AIDS. Although the interplay between HPV and HIV infections is complex, their synergistic effects in advancing cervical cancer pathology have been well-documented. Evidence indicates that immunosuppression in females with HIV infection results in more aggressive cervical cancer, often presenting at advanced stages[5,6]. Notably, HIV plays an indirect role in oncogenesis, primarily through immune suppression, which enhances the effects of high-risk HPV[13]. This role is supported by the evidence that cervical cancer is associated with a lower CD4+ cell count and lack of an ART among females living with HIV. The route of spread of cervical cancer to the brain is likely to be haematogenous. However, there are many other factors that need to be considered, including tumour emboli and host immune response[12,14]. The median interval between the diagnosis of cervical cancer and the detection of BMs has been reported to be 17.5 months[15], and the overall survival of patients with cervical cancer after the diagnosis of BMs is approximately 3-5 months[11].

Although BMs from cervical cancer are uncommon, recognizable patterns of symptoms are still observed in patients with such metastases. These symptoms include increased intracranial pressure, headache, nausea, vomiting, seizures, and weakness in the extremities[16]. The patient in this case presented with explosive headache. Because brain lesions are sequestered behind the blood-brain barrier, they differ from other tumors. However, the treatment of BMs from cervical cancer is comparable to that of BMs from other cancers. Treatment for BMs from cervical cancer is multidisciplinary, involving a combination of craniotomy, whole-brain radiation therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery, and chemotherapy. However, which treatment provides the most desirable outcome depends on various clinical factors such as the location and size of the BMs. Surgery is usually preferred when there is a solitary lesion. Systemic treatment is favorable for patients who are poor surgical candidates or have multiple lesions[14]. According to Ikeda et al[17], surgical excision of the brain lesions followed by radiotherapy results in a better survival rate than radiotherapy alone. Palliative therapies such as gamma-knife radiosurgery have focused on neurological symptom control[18]. Chemotherapy comprising a platinum-based regimen, often in combination with an angiogenesis inhibitor such as bevacizumab, is the first-line treatment for patients with recurrent, metastatic, or advanced cervical cancer.

Due to the poor physical condition of the patient in the presented case and her resolute refusal of chemotherapy, the patient only underwent surgical and radiotherapy treatments. Immunotherapies and targeted therapies typically improve survival in recurrent cases. Ni et al[19] described a rare case of BMs in a patient with cervical cancer treated with zimberelimab in combination with anlotinib after radiation therapy with temozolomide, and the patient had a progression-free survival period of nearly 10 months. However, there is limited information on the efficacy and survival benefit of these therapies in patients with HIV infection[19]. An intact immune system and a high CD4+ count are positive indicators of treatment response and tumour reduction[20].

The associated acute treatment toxicity of radiotherapy among HIV-positive female patients was seen to be an independent significant risk factor for interrupted or delayed treatment, resulting in most of patients not completing their prescribed therapies[21]. There were no significant differences in treatment outcomes, treatment response, or toxicity between females living with HIV on ART and HIV-negative women[22,23].

Females living with HIV are more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer. Due to the scarcity of cervical cancer BMs, therapeutic protocol experience is limited. In addition to the existence of the blood-brain barrier, the treatment of cervical cancer BMs appears to be unusually difficult. Even so, our patient showed good tolerance to our treatment, and the multi-modal treatment approach consisting of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation provides a potential option for prolonging life. The major limitations of this study are the absence of follow-up data beyond 7 months, and the patient’s decision to forgo chemotherapy, which is the most important component of multimodal treatment protocols.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56668] [Article Influence: 7083.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (135)] |

| 2. | Nour NM. Cervical cancer: a preventable death. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:240-244. [PubMed] |

| 3. | United Nations General Assembly. Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Ending Inequalities and Getting on Track to End AIDS by 2030. June 9, 2021. [cited 4 December 2024]. Available from: https://undocs.org/A/RES/75/284. |

| 4. | De Vuyst H, Lillo F, Broutet N, Smith JS. HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical neoplasia and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:545-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shiels MS, Copeland G, Goodman MT, Harrell J, Lynch CF, Pawlish K, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA. Cancer stage at diagnosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus and transplant recipients. Cancer. 2015;121:2063-2071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Biesma RG, Brugha R, Harmer A, Walsh A, Spicer N, Walt G. The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:239-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stelzle D, Tanaka LF, Lee KK, Ibrahim Khalil A, Baussano I, Shah ASV, McAllister DA, Gottlieb SL, Klug SJ, Winkler AS, Bray F, Baggaley R, Clifford GM, Broutet N, Dalal S. Estimates of the global burden of cervical cancer associated with HIV. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e161-e169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 84.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics - Fact Sheet. August 2, 2024. [cited 4 December 2024]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. |

| 9. | Hernández-Ramírez RU, Shiels MS, Dubrow R, Engels EA. Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from 1996 to 2012: a population-based, registry-linkage study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e495-e504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 10. | Cronin KA, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer. 2014;120 Suppl 23:3755-3757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kato MK, Tanase Y, Uno M, Ishikawa M, Kato T. Brain Metastases from Uterine Cervical and Endometrial Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fetcko K, Gondim DD, Bonnin JM, Dey M. Cervical cancer metastasis to the brain: A case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | International Agency for Research on Cancer. Biological agents: IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, volume 100B. France: IARC Publications, 2012. |

| 14. | Amita M, Sudeep G, Rekha W, Yogesh K, Hemant T. Brain metastasis from cervical carcinoma--a case report. MedGenMed. 2005;7:26. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chura JC, Shukla K, Argenta PA. Brain metastasis from cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li H, Wu X, Cheng X. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ikeda S, Yamada T, Katsumata N, Hida K, Tanemura K, Tsunematu R, Ohmi K, Sonoda T, Ikeda H, Nomura K. Cerebral metastasis in patients with uterine cervical cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:27-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chung SB, Jo KI, Seol HJ, Nam DH, Lee JI. Radiosurgery to palliate symptoms in brain metastases from uterine cervix cancer. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013;155:399-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ni BQ, Pan MM, He LX, Li T. Zimberelimab combined with systemic therapy extended tumor control in post-radiotherapy cervical cancer with brain metastases: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2024;50:740-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ferreira MP, Coghill AE, Chaves CB, Bergmann A, Thuler LC, Soares EA, Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA, Soares MA. Outcomes of cervical cancer among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women treated at the Brazilian National Institute of Cancer. AIDS. 2017;31:523-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gichangi P, Bwayo J, Estambale B, Rogo K, Njuguna E, Ojwang S, Temmerman M. HIV impact on acute morbidity and pelvic tumor control following radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shah S, Xu M, Mehta P, Zetola NM, Grover S. Differences in Outcomes of Chemoradiation in Women With Invasive Cervical Cancer by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status: A Systematic Review. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2021;11:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Simonds HM, Botha MH, Neugut AI, Van Der Merwe FH, Jacobson JS. Five-year overall survival following chemoradiation among HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma in a South African cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/