Published online Jun 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.101309

Revised: November 1, 2024

Accepted: December 5, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 18.5 Hours

Intramural pregnancy is rare, with an unclear etiology and pathophysiology. Surgical, medical, and expectant management options are available for this condition. However, most reported cases are managed surgically. Despite the risks of massive intraoperative bleeding and acute and long-term complications, uterine artery embolization is often selected. Temporary occlusion of the bilateral uterine arteries during surgery is associated with fewer complications.

We reported the case of a patient who was diagnosed with intramural pregnancy approximately one month after medical abortion. We performed laparoscopic resection with hysteroscopy. Since the lesion had abundant blood flow, we temporarily blocked the bilateral uterine arteries to prevent massive intraoperative bleeding. The surgical process went smoothly. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Temporary occlusion of the bilateral uterine arteries in the treatment of intramural pregnancy may prevent excessive uterine bleeding during surgery.

Core Tip: Intramural pregnancy is rare. There are few reports on temporary uterine artery occlusion for the treatment of intramural pregnancy. Here, we review studies on intramural pregnancy and report bilateral uterine artery occlusion during laparoscopic surgery and hysteroscopy for intramural pregnancy. The surgical process and postoperative course were uneventful.

- Citation: Song YL, Wang CF. Temporary bilateral uterine artery occlusion in the control of hemorrhage: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(18): 101309

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i18/101309.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.101309

Intramural pregnancy is rare and represents less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies[1,2]. Intramural pregnancy is characterized by the presence of the gestational sac in the uterine myometrium without any connection to the uterine cavity[3]. In intramural pregnancy, uterine rupture is potentially fatal, as it can lead to severe hemorrhage and hysterectomy. Early diagnosis of intramural pregnancy is very important. Surgical, including uterine artery embolization (UAE), medical, and expectant management options are available for this condition, and the optimal method depends on the size and location of the gestational sac, gestational age, and the patient's desire for future fertility. Here, we report laparoscopic surgery and hysteroscopy for intramural pregnancy after medical abortion. The bilateral uterine arteries were temporarily blocked during surgery.

A 41-year-old patient, gravidity 3, parity 1, artificial abortion 2, was admitted to the hospital because of a small amount of vaginal bleeding for approximately half a month after medical abortion.

The patient underwent medical abortion on December 13, 2021. The gestational sac was successfully discharged. After medical abortion, a small amount of vaginal bleeding persisted for one week. Approximately one month later, on January 27, 2022, the patient experienced vaginal bleeding again, which initially appeared to be a normal amount of menstruation. Afterward, a small amount of intermittent vaginal bleeding persisted.

She was healthy without internal medical disease and had no history of surgery.

She denied any family history of inherited disease or malignant tumors.

Physical examination revealed a normal sized uterus with no tenderness and no abnormalities in the uterine cervix or abdomen. There was a small amount of vaginal bleeding.

On February 9, 2022, her serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) level was 2649.00 mIU/mL.

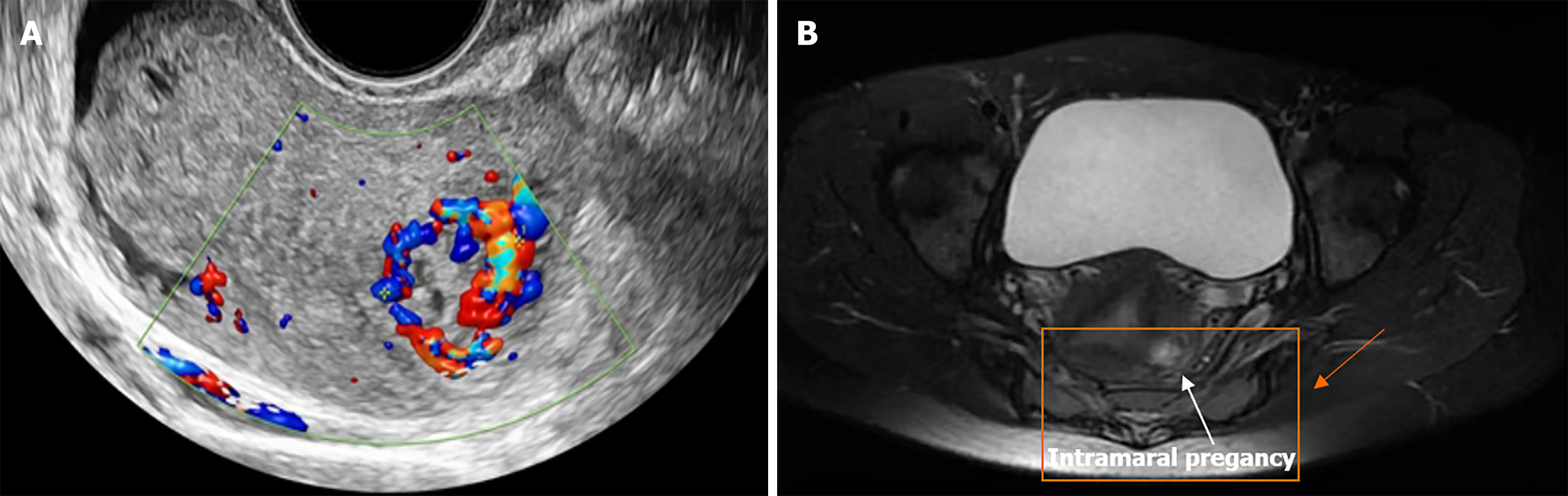

Three-dimensional transvaginal examination revealed an abnormal echo approximately 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm × 0.4 cm in size in the uterus cavity near the left uterine corner, and the echo extended to the myometrium of the uterus fundus. Color Doppler ultrasound revealed abundant blood flow around it (the “ring of fire” “sign”; Figure 1). Doppler ultrasound also revealed highly vascular tissue approximately 1.7 cm × 1.6 cm × 1.3 cm in size in the left bottom muscle layer, with detectable arterial and venous abnormalities, low resistance and high-speed blood flow, suggesting an arteriovenous fistula. T1 and T2 images on pelvic magnetic resonance imaging revealed a nodule approximately 1.5 cm in diameter with equal shadows and signals within the myometrium in the left wall of the uterus and no significant limitation in diffusion.

The diagnosis was unsure, maybe intrauterine residue, cornual pregnancy, gestational trophoblastic disease or intramural pregnancy.

Intramural pregnancy was diagnosed via surgical and pathological examinations.

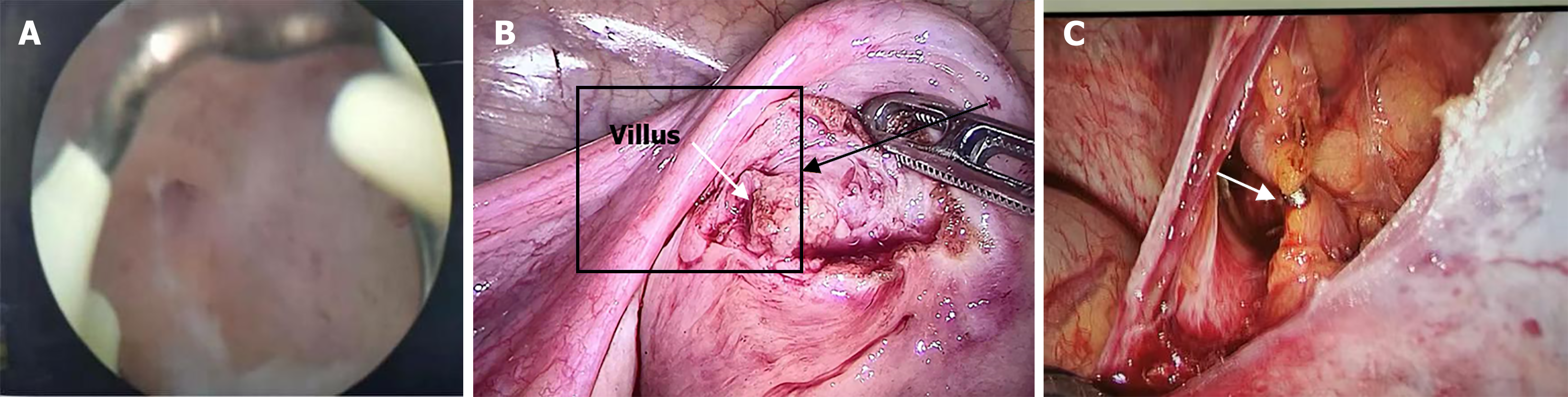

We performed hysteroscopy under general anesthesia, and although no apparent pregnant tissue was found, a membrane-like substance was observed in the uterine cavity near the left uterine horn and tubal ostia. We performed uterine curettage and scraped out a small amount of endometrial tissue.

We subsequently performed laparoscopic surgery and found no apparent adhesion or blood in the pelvic cavity. The uterus was average in size and positioned posterior, with no obvious myoma on the surface or protrusions in the bilateral uterine horns. We considered the possibility of intraoperative hemorrhage and decided to temporarily block the bilateral uterine arteries with titanium clamps. This step was essential. First, we exposed the uterine arteries by separating the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, dissecting the internal iliac artery and locating the uterine artery originating from the internal iliac artery. We then used titanium clips to block the bilateral uterine arteries intuitively. On the basis of the preoperative imaging examination, unipolar electrocoagulation was performed to cut the serous membrane layer of the left posterior wall near the uterine corner approximately 2 cm deep, where villous tissue with a diameter of approximately 1 cm was visible (Figure 2). The tissue was removed entirely. An enlarged excision measuring 0.5 cm was made in the myometrium along the outer edge of the villous tissue. Bipolar electrocoagulation was performed to stop the bleeding on the wound surface, and 1/0 absorbable sutures were used to close the uterine wound layer by layer, restoring the typical anatomical structure of the uterus. The titanium clips were removed from the bilateral uterine arteries. The surgical process went smoothly.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on the 7th postoperative day. Pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of intramural pregnancy. The serum β-hCG level was normal one week after surgery. Until July 2024, the patient was healthy. She had no desire to become pregnant again.

Intramural pregnancy is rare and represents less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies[1,2]. Intramural pregnancy is characterized by the presence of the gestational sac in the uterine myometrium without any connection to the uterine cavity[3]. Considering that intramural ectopic pregnancy is not common, there is a lack of information on the clinical features, available treatments, and long-term reproductive outcomes of patients, as most information is conveyed in case reports. We reviewed publications on intramural pregnancy from August 2017 to August 2024 and studied and reviewed 12 articles (Table 1). The cause and pathophysiology of intramural pregnancy are unclear. Adenomyosis, infertility, uterine curettage, cesarean section, myomectomy, and pelvic infection are among the potential reasons[4]. Nearly every prior procedure mentioned in the 12 studies retrieved during the search for relevant literature involved in the uterine cavity[5-16]. One possible risk factor for the case we reported here was the patient's history of medical abortions. However, there are also two cases in which there has not been a uterine cavity operation, pregnancy or any other remarkable history of gynecological diseases[5,6]. Thus, in-depth study of the causes and factors contributing to intramural pregnancy is still necessary.

| Ref. | Reproductive history | Previous uterine surgery | Other medical history | Location of pregnancy | Treatment | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Gestational age (week) | |

| 1 | Guo et al[5], 2023 | G3P2 | No | Primary dysmenorrhea | Inside the myometrium below the right uterine horn | Hysteroscopy combined with laparoscopy, used pituitrin to help find the gestational sac | Approximately 10 | - |

| 2 | Aouragh et al[6], 2024 | G0P0 | No | No | In the right side closely located to the cornua | Laparotomy | - | 6 |

| 3 | Kubo et al[7], 2024 | G2P0 | Two dilatation and curettage procedures | No | In the anterior muscular layer of the uterus | Total laparoscopic wedge resection using intraoperative ultrasonography | 45 | 6 |

| 4 | Truong et al[8], 2022 | G2P1 | Laparoscopic surgery for an ectopic pregnancy | No | In the myometrium layer close to the uterine fundus | Laparotomy, hysterectomy | Under 100 | - |

| 5 | Xie et al[9], 2022 | G1P0 | Laparoscopic salpingotomy, laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy for bilateral tubal pregnancy, hysteroscopy three times | Secondary infertility | In the left side of the anterior uterus | Laparoscopic surgery, with methotrexate injected into the myometrium | - | 7 |

| 6 | Hlinecká et al[10], 2022 | G1P0 | Cesarean section, hysteroscopic resection of retained products of conception | No | - | Laparoscopic artery occlusion and removal of pregnancy | - | 7 |

| 7 | Song et al[11], 2020 | G6P2 | Uterine curettage twice | No | In the posterior wall of the uterus | Diagnostic chemotherapy with (Etoposide+Methotrexate+Actinomycin D+cyclophosphamide), but false. | - | - |

| 8 | Nees et al[12], 2020 | G1P0 | Cesarean section | No | Near the left tubal os | Laparotomy with uterine wedge resection | - | - |

| 9 | Liu and Wu[13], 2020 | G2P1 | Ectopic pregnancy, IVF treatment and had 2 implantation failures in the first cycle of IVF. | No | In the right side of the posterior uterine | Exploratory laparoscopy, hysteroscopy and conservative surgical excision | 100 | 7 |

| 10 | Zhang et al[14], 2019 | G1P1 | Cesarean section | No | In the posterior wall below the left horn of the uterus | Laparoscopic surgery, with methotrexate injected into the myometrium | - | - |

| 11 | Vagg et al[15], 2018 | G2P2 | Open myomectomy | No | In the right uterine horn | A midline laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingectomy | - | 12 |

| 12 | Mahmoud and Mahmoud[16], 2017 | G8P7 | Cesarean section | No | Anterior myometrium of the lower uterine segment, cesarean scar pregnancy | Exploratory laparotomy | - | 8 |

Researchers believe that intramural pregnancies should be managed individually[17]. Owing to the rarity of intramural pregnancy, there are no established guidelines for treatment at present. Various factors, such as the patient's state, conception location, gestational age, and desire to preserve fertility, influence the treatment selected for intramural pregnancy. A range of management strategies, including methotrexate treatment, laparoscopic surgery, laparotomy surgery, and expectant management, have been attempted. Methotrexate is administered systemically via a local injection and has been used successfully to arrest pregnancy development in cases of intramural pregnancy[18-20]. Katano et al[20] managed intramural pregnancy in the 8th week of gestation, as evidenced by an hCG level of 4000 IU/L, with laparoscopic and transvaginal local injections of methotrexate and reported that such an approach is an effective way to preserve reproductive potential. Memtsa et al[21] described a case in which the hCG level was 1159 IU/L and was managed with an injection of methotrexate. The hCG test was negative 6 weeks thereafter. The patient experienced transient severe lower abdominal pain. The major disadvantages of medical treatment for ectopic pregnancy are the need for prolonged follow-up and uncertainty about the effects on future fertility and pregnancies[22]. In our case, intramural pregnancy is difficult to diagnose via imaging examination and requires intraoperative and pathological examination for diagnosis; however, the patient refused treatment with methotrexate. Therefore, we adopted conservative surgical management.

Expectant management was occasionally applied in a case report in which the serum β-hCG level was 9.5 mIU/mL[23]. After a literature review, most of the case reports involved conservative surgical management, such as laparoscopic surgery[15], hysteroscopic surgery[24], and UAE [25]. Shen et al[26] reported that 10 of the 17 cases reported were successfully managed with laparoscopic surgery, indicating that laparoscopic surgery was more widely performed than other methods were for treating early intramural pregnancy; moreover, 8/12 cases reported were also treated with laparoscopic surgery. However, it is important to note that patients in mid- or late-term pregnancy should consider a cesarean section as their first option since they may experience excessive bleeding and their uterus may not be able to tolerate laparoscopic surgery. Auer-Schmidt et al[24] successfully managed intramural pregnancy with hysteroscopic surgery using a resectoscope loop to resect the sac through a visualized false tract. However, most of the time, hysteroscopy is used to examine the uterine cavity during laparoscopic surgery.

Once we perform conservative laparoscopic surgery, we should consider the situation of intraoperative bleeding and avoid emergency hysterectomy due to excessive bleeding during surgery. Clinical doctors evaluate intraoperative bleeding via examinations to determine the richness of blood flow signals, lesion size, and hCG values, similar to the treatment of caesarean scar pregnancy. Taking massive intraoperative bleeding into account, some researchers have implemented UAE[27] to help maintain fertility. UAE plays a vital role in decreasing bleeding and has been widely used in postpartum hemorrhage, symptomatic uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, and caesarean scar pregnancy. As UAE has become widely performed, concerns about complications have increased. Acute complications include fever, pain, nausea, vomiting, and lower limb vascular embolism. The long-term complications of UAE can include endometrial ischemic necrosis, uterine intrauterine adhesions, ovarian failure, and subsequent infertility[28]. Homer and Saridogan[29] reported that UAE is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage. Another report[30] revealed a decrease in fertility in patients who previously underwent UAE.

Compared with UAE, temporary occlusion of the uterine artery is a promising new approach that causes less postoperative pain[31] and fewer unfavorable pregnancy outcomes[32], reduces intraoperative bleeding without increasing the operative time[33] and does not influence the function of the ovary[34] since uterine artery occlusion is temporary. Li et al[35] managed intramural ectopic pregnancy with temporary aortic balloon occlusion via the femoral artery during cesarean delivery, decreasing hemorrhage, preventing blood transfusion, and maintaining fertility. Preoperative endovascular balloon occlusion can successfully prevent heavy bleeding. However, serious complications may occur, such as thrombosis, arterial pseudoaneurysms, acute lower extremity ischemia, and arterial rupture[36]. There is currently no research published on the use of uterine artery occlusion with titanium clips in the treatment of intramural pregnancy. Titanium surgical clips were first used in combination with an injection of vasopressin by Shao et al[37] to decrease uterine vascularization during the surgical excision of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. After that, more cases involved temporary occlusion of the bilateral uterine arteries. In another case, researchers demonstrated that a transvaginal laparoscopic procedure with temporary occlusion of the bilateral uterine arteries could terminate the cervical pregnancy[38]. Temporary occlusion of the uterine arteries is an effective strategy to avoid serious intraoperative bleeding from conditions such as uterine fibroids, uterine adenomyosis, tubal interstitial pregnancy, and cornual pregnancy. Shen et al[26] described 8 cases of intramural pregnancy treated with laparoscopic surgery or hysteroscopic surgery without preoperative intervention and reported that, in most cases, the intraoperative bleeding volume was greater than 100 mL, up to 400 mL. In our case, we temporarily occluded the bilateral uterine arteries during laparoscopic surgery to reduce intraoperative bleeding (intraoperative bleeding was approximately 20 mL) and successfully halt the progression of the pregnancy. Here, we recommend temporary occlusion of the uterine artery when the patient is at risk of excessive uterine bleeding during surgery.

Attention is needed here. Temporary occlusion of the uterine artery with titanium clips must be performed by experienced operators who are familiar with the anatomy of the pelvic organs and pelvic vessels. The operators should carefully expose the uterine artery, which is concealed and sometimes difficult to expose. By dissecting the internal iliac artery and locating the uterine artery originating from the internal iliac artery, operators can free and temporarily block the uterine artery. All operators should pay attention to the ureter and important pelvic vessels. In situations in which the uterine artery cannot be identified, causing occlusion to fail, uterine artery tears or heavy bleeding can occur, and temporarily occlusion of the internal iliac artery can be a remedial measure. There are several serious complications, including thromboembolism, lower organ ischemia and reperfusion injury, and aortic damage. The contraindications include dissecting aneurysms, substantial aortic meandering, and calcification.

Unfortunately, long-term follow-up, especially of fertility status, has not been performed in most investigations. This is also a limitation in our case. We recommend large case series studies to ascertain long-term outcomes.

Significant challenges are associated with managing intramural pregnancy. When selecting strategies for treatment, it is important to consider individual differences, particularly expectations for fertility and quality of life. Once patients with intramural pregnancy are managed, a thorough and unbiased evaluation of the benefits and drawbacks of each treatment option is essential.

We reported a case of intramural pregnancy approximately one month after medical abortion. We performed hysteroscopy and temporarily occluded the bilateral uterine arteries during laparoscopic surgery. The postoperative course was uneventful. We recommend temporary occlusion of the uterine arteries in patients at risk of excessive uterine bleeding during surgery.

We want to express our thanks to the patients, doctors, nurses, and other medical staff at Zhejiang Hospital for agreeing to participate in this study.

| 1. | Fadhlaoui A, Khrouf M, Nouira K, Chaker A, Zhioua F. Ruptured intramural pregnancy with myometrial invasion treated conservatively. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:965910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ko HS, Lee Y, Lee HJ, Park IY, Chung DY, Kim SP, Park TC, Shin JC. Sonographic and MR findings in 2 cases of intramural pregnancy treated conservatively. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ginsburg KA, Quereshi F, Thomas M, Snowman B. Intramural ectopic pregnancy implanting in adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen X, Gao L, Yu H, Liu M, Kong S, Li S. Intramural Ectopic Pregnancy: Clinical Characteristics, Risk Factors for Uterine Rupture and Hysterectomy. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:769627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Guo Y, Feng T, Du X. A detective of intramural ectopic pregnancy: The use of pituitrin under hysteroscopy combined with laparoscopy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e33379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aouragh A, Boukroute M, Aloua YE, Regragui A, Bellajdel I, Taheri H, Saadi H, Mimouni A. Intramural pregnancy at 6 and 8 weeks gestation with no predisposing factors: As two uncommon case reports. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19:2390-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kubo K, Fujikawa A, Mitoma T, Mishima S, Ohira A, Kirino S, Maki J, Eto E, Masuyama H. Total laparoscopic wedge resection for an intramural ectopic pregnancy using an intraoperative ultrasound system: A case report. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2024;17:e13303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Truong DP, Pham TH, Nguyen PN, Ho QN. Misdiagnosis of intramural ectopic pregnancy and invasive gestational trophoblastic disease on ultrasound: A challenging case at Tu Du Hospital in Vietnam in COVID-19 pandemic peak and mini-review of literature. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:4821-4827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xie QJ, Li X, Ni DY, Ji H, Zhao C, Ling XF. Intramural pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:2871-2877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Hlinecká Kristýna, Lisá Zdeňka, Richtárová Adéla, Kužel David. Intramyometrial pregnancy after hysteroscopic resection of retained products of conception - a case report. Ceska Gynekol. 2022;87:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Song QY, Yang F, Luo H. A Case of Intramural Pregnancy: Differential Diagnosis for Distinguishing from Retained Products of Conception and Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2020;9:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nees J, Faigle-Krehl G, Brucker J, Leucht D, Platzer LK, Flechtenmacher C, Sohn C, Wallwiener M. Intramural pregnancy: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2020;27:e00215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Y, Wu Y. Intramyometrial pregnancy after cryopreserved embryo transfer: a case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang Q, Xing X, Liu S, Xie X, Liu X, Qian F, Liu Y. Intramural ectopic pregnancy following pelvic adhesion: case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1507-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vagg D, Arsala L, Kathurusinghe S, Ang WC. Intramural Ectopic Pregnancy Following Myomectomy. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:2324709618790605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mahmoud OA, Mahmoud MZ. A rare case of ectopic pregnancy in a caesarean section scar: a case report. BJR Case Rep. 2017;3:20170010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ntafam CN, Sanusi-Musa I, Harris RD. Intramural ectopic pregnancy: An individual patient data systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. 2024;21:100272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ong C, Su LL, Chia D, Choolani M, Biswas A. Sonographic diagnosis and successful medical management of an intramural ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38:320-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peng Y, Dai Y, Yu G, Jin P. High-intensity focused ultrasound ablation combined with systemic methotrexate treatment of intramural ectopic pregnancy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Katano K, Ikuta K, Matsubara H, Oya N, Nishio M, Suzumori K. A case of successful conservative chemotherapy for intramural pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:744-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Memtsa M, Jamil A, Sebire N, Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Diagnosis and management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hafner T, Aslam N, Ross JA, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. The effectiveness of non-surgical management of early interstitial pregnancy: a report of ten cases and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bernstein HB, Thrall MM, Clark WB. Expectant management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:826-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Auer-Schmidt MM, Rahimi G, Wahba AH, Schmidt T. Hysteroscopic management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang S, Dong Y, Meng X. Intramural ectopic pregnancy: treatment using uterine artery embolization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:241-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shen Z, Liu C, Zhao L, Xu L, Peng B, Chen Z, Li X, Zhou J. Minimally-invasive management of intramural ectopic pregnancy: an eight-case series and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;253:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Niu X, Tang Y, Li S, Ni S, Zheng W, Huang L. The feasibility of laparoscopically assisted, hysteroscopic removal of interstitial pregnancies: A case series. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:3447-3455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Qi F, Zhou W, Wang MF, Chai ZY, Zheng LZ. Uterine artery embolization with and without local methotrexate infusion for the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Homer H, Saridogan E. Uterine artery embolization for fibroids is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:324-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Serres-Cousine O, Kuijper FM, Curis E, Atashroo D. Clinical investigation of fertility after uterine artery embolization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:403.e1-403.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hald K, Langebrekke A, Kløw NE, Noreng HJ, Berge AB, Istre O. Laparoscopic occlusion of uterine vessels for the treatment of symptomatic fibroids: Initial experience and comparison to uterine artery embolization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Holub Z, Mara M, Kuzel D, Jabor A, Maskova J, Eim J. Pregnancy outcomes after uterine artery occlusion: prospective multicentric study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1886-1891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Istre O. Uterine artery occlusion for the treatment of symptomatic fibroids: endoscopic, radiological and vaginal approach. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2005;14:167-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Liu L, Li Y, Xu H, Chen Y, Zhang G, Liang Z. Laparoscopic transient uterine artery occlusion and myomectomy for symptomatic uterine myoma. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Li S, Liu H, Li X, Liu Z, Li Y, Li N. Transfemoral temporary aortic balloon occlusion in surgical treatment of second trimester intramural ectopic pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42:716-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Xu W, Liu Z, Ren Q, Dai C, Wang B, Peng Y, Gao L. Treatment of infected placenta accreta in the uterine horn by transabdominal temporary occlusion of internal iliac arteries: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Shao MJ, Hu MX, Hu M. Temporary bilateral uterine artery occlusion combined with vasopressin in control of hemorrhage during laparoscopic management of cesarean scar pregnancies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Jin L, Ji L, Shao M, Hu M. Laparoscopic temporary bilateral uterine artery occlusion - a successful pregnancy outcome of heterotopic intrauterine and cervical pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;41:668-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/