Published online Jun 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i17.98529

Revised: November 9, 2024

Accepted: January 21, 2025

Published online: June 16, 2025

Processing time: 230 Days and 20.3 Hours

Motorcycle accidents often result in abdominal trauma in patients seeking emer

A 21-year-old man, who was involved in a motorcycle collision at 70 km/hour after consuming a large meal, presented with hypotension. Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness. Laboratory test results indicated elevated amy

Gastric rupture following blunt trauma is fatal. However, patients without severe complications can recover through surgical interventions and postoperative care.

Core Tip: Motorcycle accidents often result in abdominal trauma. Owing to the protective function of the anterior rib cage, gastric rupture is rare. We present a case of a 21-year-old man involved in a collision after consuming a large meal, leading to multiple gastric ruptures and pancreatic, splenic, and hepatic injuries. Surgical interventions included primary closure of the gastric wall, splenectomy, and partial hepatectomy. Despite the severity, the patient recovered after receiving appropriate postoperative care. This report underscores the importance of prompt surgical interventions for managing traumatic gastric injuries and ensuring favorable outcomes, even in complex cases.

- Citation: Cho IS, Park CH, Lee JW. Double-sided gastric perforation after a motorcycle accident in Korea: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(17): 98529

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i17/98529.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i17.98529

Patients referred to the emergency room for motorcycle accidents experience various traumatic events, with blunt trauma being the most common cause of abdominal trauma. While solid organs such as the liver and spleen are the most affected in this type of trauma, a number of hollow viscus injury cases have been reported. In these cases, injuries to the duode

Abdominal pain.

A 21-year-old male patient with no relevant medical history was referred to the Division of Trauma Surgery and Surgical Critical Care via the emergency room following a motorcycle accident. The patient was travelling at 70 km/hour when he collided with another motorcycle in front of him.

Abdominal inspection revealed right upper quadrant abrasion with no external bruising (Figure 1). On palpation, the abdomen was tender, guarded, and relatively flat. An open wound with right leg instability was observed, suggesting a fracture.

Initial laboratory test results indicated a hemoglobin level of 13.5 g/dL, platelet count of 294000/μL, and normal prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed pneumoperitoneum, hemoperitoneum, and discontinuation of the stomach wall, suggesting gastric perforation along with injuries such as pancreatic body and tail contusion, splenic laceration, and left hepatic contusion (Figure 2). Lung CT showed bilateral lung contusions with no thoracic cage fractures, whereas brain CT revealed no specific findings. Active contrast leakage was detected in the left and right gastroepiploic arteries.

The patient was diagnosed with left gastric bleeding; right gastroepiploic artery bleeding with gastric perforation; hepatic, splenic, pancreatic, and pulmonary contusions; and right tibial fractures. The patient’s Injury Severity Score was 25 points.

Prompt surgery was decided. As the operating room was not yet ready, angiographic embolization was performed for the meantime before surgery at 2 hours after the patient’s arrival in the emergency room. Our institution is not a government-designated regional trauma center and does not have a dedicated operating room for emergency trauma patients. Nevertheless, we had to treat this patient because other regional trauma centers could not accept the patient. At the time of this patient’s arrival, all operating rooms were full with regular surgical schedules. Thus, while waiting until additional operating rooms and surgical staff were available, we had to stabilize the patient by performing angiography in collaboration with the intervention team, which had immediate access.

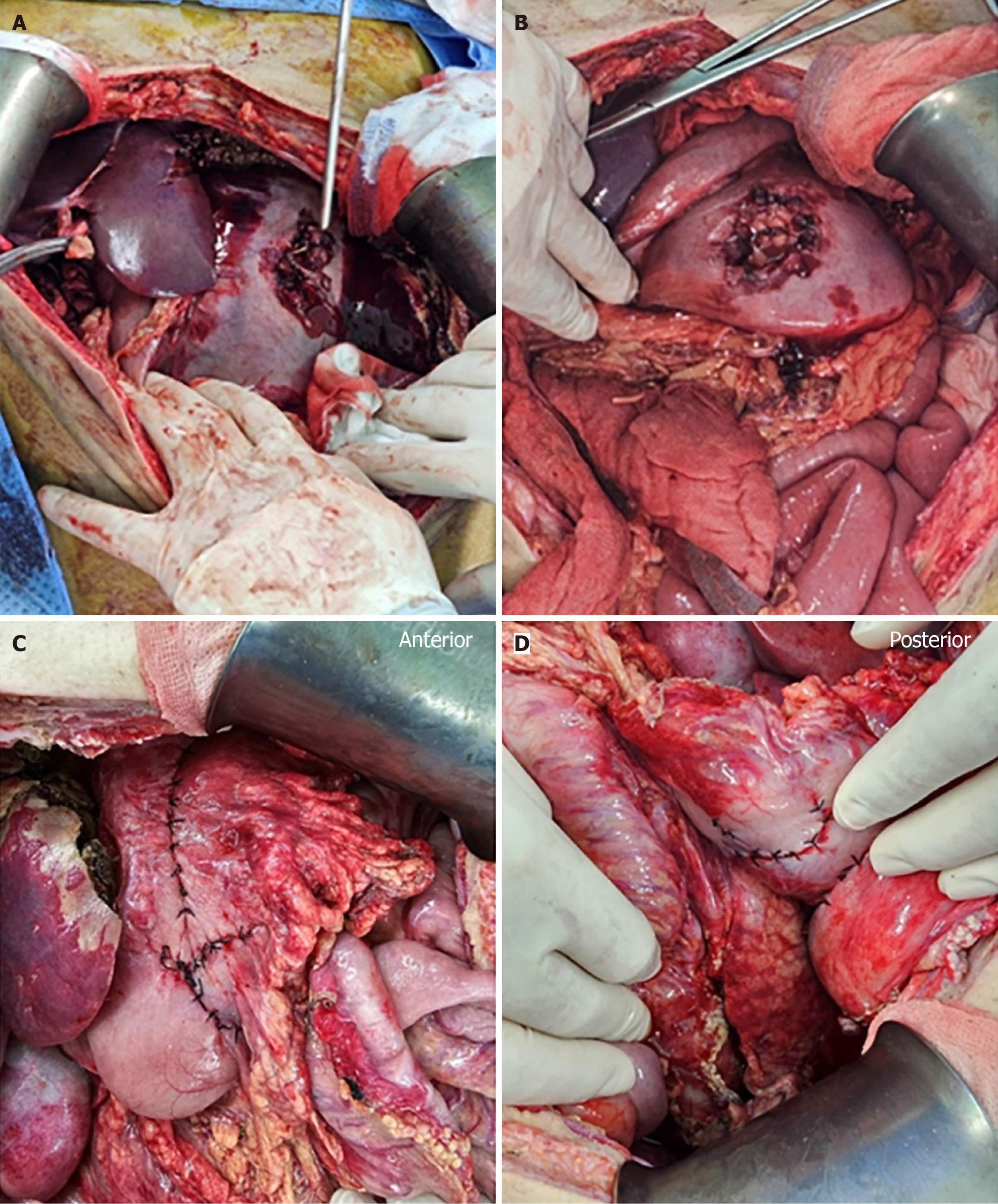

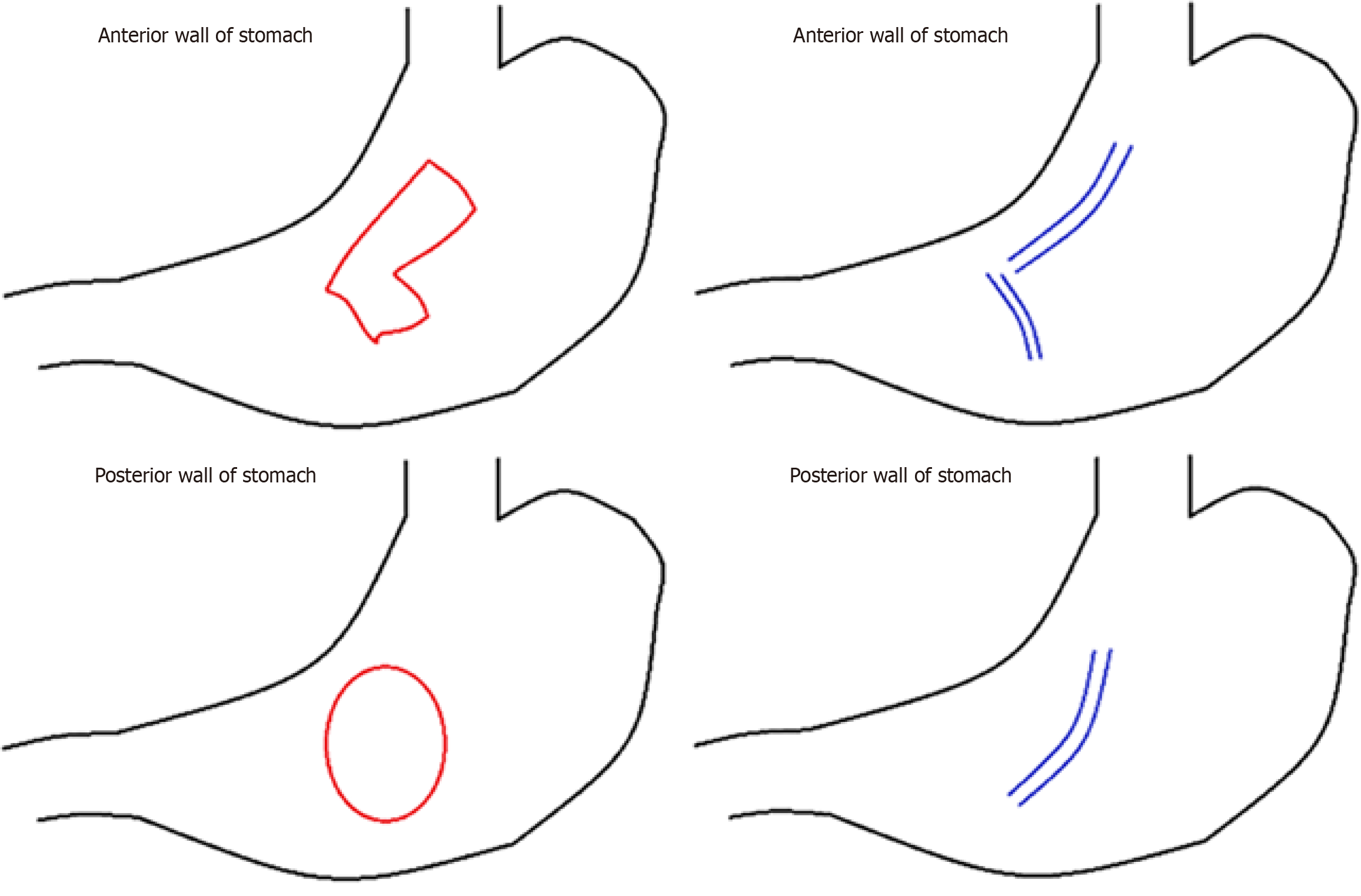

Emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed at 1 hour after embolization. Significant amounts of blood and hematoma were found in the abdominal compartment. Additionally, gastric contents, mainly consisting of noodles, were noted throughout the abdominal cavity and omentum. Along the long axis of the stomach, a full-thickness irregularly shaped perforation measuring 10 cm was observed on the anterior wall. Furthermore, a full-thickness oval perforation measuring 8 cm × 10 cm was identified on the posterior wall in the midbody (Figure 3A and B). The left lateral section of the liver was dissected because it was almost detached due to the injury and extensive venous bleeding was observed. A 10 cm injury to the right liver capsule, contusion of the dissected pancreas, and splenic laceration with oozing of blood were also noted. Splenectomy and left lateral sectionectomy were quickly performed to arrest active hemorrhage from the lacerated and flattened spleen and liver. The anterior and posterior stomach walls were approximated. Considering that the vital signs were unstable intraoperatively and the small bowel was edematous because of massive intraoperative hydration, the abdomen was temporarily closed with gauze packing for damage control to minimize the traumatic insult of surgery.

The patient was intubated for mechanical ventilation. Postoperative laboratory results indicated a slight decrease in hemoglobin level (11.8 g/dL) and platelet count (164000/μL), an increase in the PT/international normalized ratio (1.33), and normal aPTT after red blood cell transfusion (two units). Vigorous resuscitation, including correction of the lethal triad of trauma with deep sedation, was performed in the intensive care unit prior to the second surgery. Delayed surgery was performed at 48 h after the primary surgery. During the second surgery, no further bleeding was observed, and the primary site of stomach injury was wedge-resected using linear staplers (100 mm; GIA stapler with DST Series techno

With the patient’s gradual stabilization, spontaneous closure of the pancreatic fistula occurred after five weeks, and all abdominal percutaneous drains were removed. The patient also sustained a right leg fracture and was accordingly transferred to the orthopedic surgery department. The patient was discharged on POD 50. This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center (approval No. 2023-10-068). The patient provided verbal informed consent for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

This report presents a rare case of double-sided gastric perforation resulting from blunt trauma. The first documented instance of gastric rupture after blunt abdominal trauma was reported in 1922. Since then, only a few cases have been reported because of its rarity, with an incidence rate of < 1.7% among all abdominal traumas[3-6]. The infrequency of gastric rupture in blunt trauma can be attributed to factors such as the protective shielding provided by the anterior thoracic cage and the substantial thickness of the stomach wall[4,7]. Blunt gastric ruptures can occur in various locations within the stomach. Perforations are predominantly located on the anterior wall (40%), followed by the greater curvature, lesser curvature (15%), and posterior wall (15%)[8]. Most ruptures are solitary, and only five documented cases of multiple gastric ruptures following blunt trauma have been reported[9-13]. Roupakias et al[9] reported a case of an 18-month-old female patient with a ruptured greater curvature and posterior wall resulting from a motor vehicle accident. Other studies identified the prepyloric region and greater curvature as frequent rupture sites, as reported by Gheewala et al[10] and Straub[11]. Ishikawa et al[12] reported a case involving four separate perforation sites on the anterior wall. Mushtaq and Aslam[13] reported a case similar to ours, demonstrating both anterior and posterior wall ruptures fo

Traumatic gastric injuries are primarily caused by three mechanisms, similar to those of traumatic intestinal injuries: Direct impact, deceleration, and increased luminal pressure[7,14-16]. However, clinical lesions stemming from gastric injuries often reflect a combination of these three mechanisms to varying degrees, and determining the exact causative mechanism[5,7,15]. First, a direct impact involves the transmission of energy in the form of a shockwave from the surface to the core of the body, thereby inducing a vice-like compression effect. The impact velocity significantly influences the energy intensity, resulting in injuries characterized by bruising, tearing, and lacerations that typically manifest on the side opposite the origin of the force. Posterior wall perforations can also occur less commonly, as in our case, via a mechanism similar to that previously described. The second mechanism, deceleration, is closely associated with an abrupt change in velocity as the body transitions from a high-speed state to a complete cessation of motion upon collision with an obstacle. During this sudden deceleration, the gastrointestinal tract underwent translational back-and-forth motion. The nature of the resulting injuries depends on the tissue strength, fixation, and degree of displacement. The third mechanism involves the abrupt compression of the abdominal cavity, resulting in elevated luminal pressure. When sudden and strong forces are applied to a stomach filled with air and food materials, they can lead to blowout of the hollow viscus[5,15,16].

Abdominal pain is a typical clinical manifestation of gastric rupture, and abdominal palpation may reveal rigidity and peritoneal signs. However, many patients with gastric ruptures have an altered state of consciousness or are intoxicated, making it difficult to assess their signs and symptoms. Radiological diagnoses can be made based on evidence of pneumoperitoneum. Ultrasonography is a rapid and convenient tool for patients with trauma. Using an ultrasonic device, we observed free fluid in the abdominal cavity on the bedside. CT, which is currently the gold-standard diagnostic tool for visceral injuries[17,18], may reveal discontinuities in the stomach wall, extravasation of luminal contents, and free air. Other findings that may help in diagnosis include abnormal enhancement and focal thickening of the gastric wall, surrounding abscesses, and fatty infiltration. However, in 13% of patients with gastric rupture, CT may show negative findings, making prompt diagnosis difficult[6,18,19].

Major abdominal trauma often results in rupture, accompanied by damage to other major organs in the thoracic or abdominal cavity. Multiple studies have demonstrated the high likelihood of gastric lacerations occurring alongside other injuries[4,6,19,20]. Shinkawa et al[7] reported that eight out of 14 patients with gastric rupture in their study sustained additional injuries involving both the abdominal and thoracic regions, four suffered from injuries to the brain, and eight had fractured limbs. Interestingly, only five patients had intra-abdominal lesions without any other accompanying injuries. The liver is the most frequently affected solid organ in cases of associated solid organ injuries, with a prevalence of 36%, followed by the pancreas and spleen (29%)[4,7]. In our patient’s case, splenic and hepatic injuries were noted on preoperative CT, but active contrast leakage was detected in the coronary artery of the stomach; initial angioembolization was performed before exploration to stabilize the patient. Splenectomy and partial hepatectomy were performed because of hepatic and splenic lacerations. However, different perspectives regarding the prevalence of accompanying organ injuries exist. Ueda et al[21] reported that most patients with gastric lesions did not experience additional complications; out of 26 patients studied, only 10 had concomitant organ injury, with the spleen being the most commonly affected.

Prompt surgical intervention is essential when gastric perforation or rupture is suspected. Owing to evidence bias, the overall mortality rate associated with gastric injury ranges from 0% to 66%[5,22,23]. For patients undergoing surgery within 8 hours of injury, the mortality rate is as low as 2%. However, delays of 16-24 hours or beyond 24 hours sig

This study has certain limitations. First, it lacks a comparative analysis of similar cases in the existing literature. Second, because the patient needed to return to his home country, long-term follow-up could not be performed. The absence of long-term follow-up data limits our understanding of the patient's recovery trajectory and potential long-term complications.

Treatment should be considered for traumatic gastric perforation, with a focus on the severity of injury, mechanism of occurrence, time and size of the last meal, and accompanying organ damage in the abdominal cavity. Accurate diagnosis and timely surgical intervention are crucial for improving patient prognosis.

| 1. | Isenhour JL, Marx J. Advances in abdominal trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:713-733, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Talton DS, Craig MH, Hauser CJ, Poole GV. Major gastroenteric injuries from blunt trauma. Am Surg. 1995;61:69-73. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Franklin GA, Casós SR. Current advances in the surgical approach to abdominal trauma. Injury. 2006;37:1143-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bruscagin V, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, Abrantes WL, Souza HP, Neto G, Dalcin RR, Drumond DA, Ribas JR. Blunt gastric injury. A multicentre experience. Injury. 2001;32:761-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aboobakar MR, Singh JP, Maharaj K, Mewa Kinoo S, Singh B. Gastric perforation following blunt abdominal trauma. Trauma Case Rep. 2017;10:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lai CC, Huang HC, Chen RJ. Combined stomach and duodenal perforating injury following blunt abdominal trauma: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2020;20:217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shinkawa H, Yasuhara H, Naka S, Morikane K, Furuya Y, Niwa H, Kikuchi T. Characteristic features of abdominal organ injuries associated with gastric rupture in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 2004;187:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tejerina Alvarez EE, Holanda MS, López-Espadas F, Dominguez MJ, Ots E, Díaz-Regañón J. Gastric rupture from blunt abdominal trauma. Injury. 2004;35:228-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roupakias S, Tsikopoulos G, Stefanidis C, Skoumis K, Zioutis I. Isolated double gastric rupture caused by blunt abdominal trauma in an eighteen months old child: a case report. Hippokratia. 2008;12:50-52. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Gheewala HM, Wagh S, Chauhan SA, Devlekar SM, Bhave S, Balsarkar DJ. Isolated Double Gastric Perforation in Blunt Abdominal Trauma-a Case Report. Indian J Surg. 2017;79:254-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Straub G. [Double stomach rupture as isolated injury]. Unfallchirurgie. 1993;19:112-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ishikawa K, Ueda Y, Sonoda K, Yamamoto A, Hisadome T. Multiple gastric ruptures caused by blunt abdominal trauma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:1000-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mushtaq SM, Aslam MN. Isolated double gastric rupture as a result of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:351-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bège T, Brunet C, Berdah SV. Hollow viscus injury due to blunt trauma: A review. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:61-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arró Ortiz C, Hughes V, Ramallo D. Gastric perforation after blunt abdominal trauma: first case report in Argentina. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022:rjac394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Case ME, Nanduri R. Laceration of the stomach by blunt trauma in a child: a case of child abuse. J Forensic Sci. 1983;28:496-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim HC, Shin HC, Park SJ, Park SI, Kim HH, Bae WK, Kim IY, Jeong DS. Traumatic bowel perforation: analysis of CT findings according to the perforation site and the elapsed time since accident. Clin Imaging. 2004;28:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Solazzo A, Lassandro G, Lassandro F. Gastric blunt traumatic injuries: A computed tomography grading classification. World J Radiol. 2017;9:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Champion HR, Shackford SR. Organ injury scaling. VI: Extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma. 1995;39:1069-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, McAninch JW, Pachter HL, Shackford SR, Trafton PG. Organ injury scaling, II: Pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma. 1990;30:1427-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ueda S, Okamoto N, Seki T, Matuyama T. A large gastric rupture due to blunt trauma: a case report and a review of the Japanese literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;2021:rjaa521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yajko RD, Seydel F, Trimble C. Rupture of the stomach from blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1975;15:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Courcy PA, Soderstrom C, Brotman S. Gastric rupture from blunt trauma. A plea for minimal diagnostics and early surgery. Am Surg. 1984;50:424-427. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Weledji EP. An Overview of Gastroduodenal Perforation. Front Surg. 2020;7:573901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Kujath P, Schwandner O, Bruch HP. Morbidity and mortality of perforated peptic gastroduodenal ulcer following emergency surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387:298-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hota PK, Babu M, Satyam G, Praveen AC. Traumatic Gastric Rupture Following Blunt Trauma Abdomen: A Case Series. Bali Med J. 2014;3:49. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/