Published online Apr 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i12.99229

Revised: November 29, 2024

Accepted: December 13, 2024

Published online: April 26, 2025

Processing time: 173 Days and 12.1 Hours

Esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage (EJAL) is a severe complication following gastrectomy for gastric cancer, typically treated with drainage and nutritional support. We report a case of intraluminal drain migration near the esophagojejunal anastomosis (EJA), resulting in persistent drainage and mimicking EJAL after total gastrectomy.

A 64-year-old male underwent open total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y recon

Intraluminal drain migration is a rare complication following gastric surgery but should be considered when persistent drainage occurs.

Core Tip: Intraluminal drain migration after abdominal surgery is an uncommonly reported complication that can mimic anastomotic leakage. We present a rare case of abdominal drain migration adjacent to an esophagojejunostomy following total gastrectomy. This report includes a literature review to briefly summarize the incidence, pathophysiology, and diagnostic approaches for intraluminal drain migration.

- Citation: Janež J, Romih J, Čebron Ž, Gavric A, Plut S, Grosek J. Intraluminal migration of a surgical drain near an anastomosis site after total gastrectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(12): 99229

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i12/99229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i12.99229

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide[1]. The current standard of care for achieving curative resection in gastric cancer involves the complete removal of the tumor with an adequate safety margin, necessitating either partial gastrectomy or total gastrectomy[2]. Following total gastrectomy, esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage (EJAL) remains a possible complication associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Conservative management of EJAL with drainage and nutritional support is the most common approach[3].

However, despite the routine use of abdominal drains in the conservative management of EJAL, surgeons must remain vigilant regarding potential complications associated with their use. One such complication is the penetration of a surgical drain through the bowel, a well-recognized but rarely reported occurrence[4].

We present a case of intraluminal drain migration adjacent to an esophagojejunostomy following total gastrectomy, which manifested as persistent drainage and mimicked an anastomotic leak.

A 64-year-old male patient with a history of arterial hypertension underwent open total gastrectomy for the treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma.

A Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy was performed, and two 7-mm silicone drains (Ch 21) were placed adjacent to the anastomosis. The operation was completed without complications. Pathological examination of the resected specimen confirmed a T1b N0 R0 gastric adenocarcinoma.

The patient has a history of arterial hypertension.

The patient's family history is negative for gastric carcinoma.

On postoperative day (POD) 4, the patient experienced clinical deterioration with signs of sepsis, including confusion.

Inflammatory markers were elevated significantly (C-reactive protein 341 mg/L, leukocytes 8.1 × 109/L, procalcitonin 1.07 ng/mL).

A computed tomography (CT) scan with oral contrast revealed an air-filled fluid collection (7 cm × 3 cm × 2.7 cm) located to the left of the esophagojejunal anastomosis (EJA) and anterior to the spleen, with oral contrast filling the collection (Figure 1).

EJAL, intra-abdominal abscess, diffuse peritonitis, sepsis.

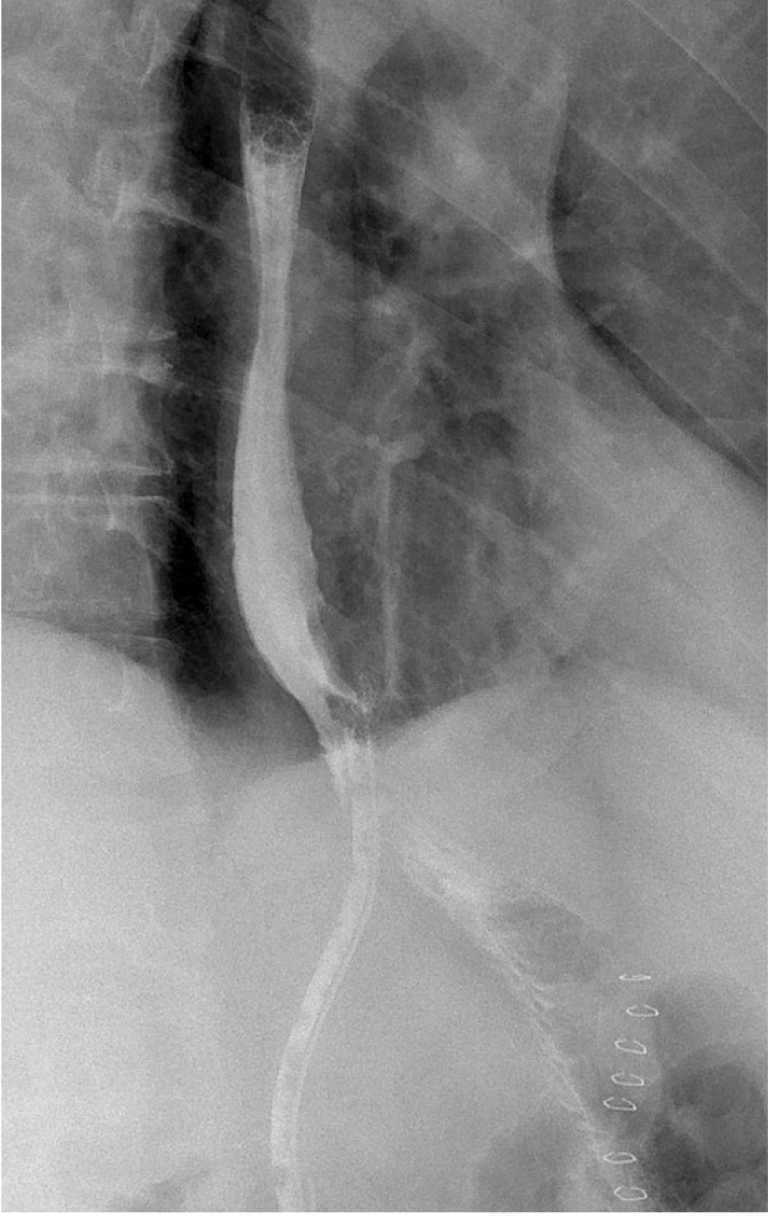

Due to clinical signs of peritonitis, uncontrolled sepsis, and CT findings suggestive of anastomotic dehiscence, surgical re-exploration was deemed necessary. Intraoperatively, we found an abscess cavity anterior to the spleen without clear evidence of an EJAL. Surgical drainage of the abscess and lavage of the peritoneal cavity were performed. We repositioned the first drain behind the EJA, the second left to the EJA, and added a third drain in the proximity of the duodenal stump. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated, and the patient was kept nil per os with total parenteral nutrition. On POD 7 after the initial surgery, antibiotic therapy was tailored to the specific bacteria isolated from cultures, and bowel function was initiated with enema stimulation. On POD 13, the patient inadvertently removed the left abdominal drain. On POD 18, a contrast swallow study revealed rapid opacification of the remaining abdominal drain without evidence of extraluminal contrast extravasation (Figure 2). The remaining drain, located a few centimeters from the EJA, was removed due to the absence of drainage.

The patient's clinical condition remained stable in the subsequent days, with no signs of intra-abdominal infection. Inflammatory markers progressively declined, reaching normal levels by POD 21. On POD 24, antibiotics were discontinued, and the patient was transferred to the general ward. However, persistent drainage (25-75 mL daily) from the remaining drain continued. Repeated oral contrast swallow studies (performed on POD 26, 43, and 53) were concerning for an EJA leak, demonstrating contrast filling of the drain without evidence of extraluminal extravasation. On POD 32, the patient was given oral methylene blue, and shortly thereafter, blue staining was observed in the drainage from the abdominal drain. On POD 54, the abdominal drain was shortened by 2 cm.

Due to persistent drainage, an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed on POD 59. The findings were unexpected: Approximately 5 cm of the abdominal drain had migrated into the esophagus, with the entry point identified as a perforation located 2 cm distal to the anastomosis. Notably, the EJA itself was intact, without any evidence of dehiscence (Figure 3). Consequently, the drain was repositioned from the esophageal lumen into the peritoneal cavity under endoscopic guidance. The jejunal defect was noted to be only a few millimeters in size. A nasogastric tube was inserted, and no further intervention was deemed necessary.

On POD 67, a repeat contrast study demonstrated no evidence of extraluminal contrast extravasation or filling of the abdominal drain. Subsequently, the abdominal drain and nasogastric tube were removed, and oral feeding was initiated. The patient tolerated oral intake well, reported no abdominal pain, and inflammatory markers remained within normal limits. A CT scan with oral contrast on POD 73 confirmed the absence of an EJAL. He was discharged from the hospital a few days later.

We present a case of prolonged treatment for suspected EJAL caused by the migration of an abdominal drain, leading to perforation of the jejunum 2 centimeters under the anastomotic site.

The true incidence of intraluminal drain migration remains unknown[4]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case at our institution. A study by Wilmot et al[5] specifically addressed intraluminal drain migration in the context of esophageal surgery. In their retrospective analysis, migration of surgical drain into the lumen at or near the anastomosis was described in 4 of 254 patients (1.6%) after esophagogastrectomy, representing 7% of patients who developed an anastomotic leak in their cohort. However, no similar study has specifically addressed intraluminal drain migration in the context of gastric surgery. Medical devices like sponges, hernia meshes, and gastrostomy tubes can penetrate the gastric or intestinal wall through various mechanisms[4]. The mechanism of bowel injury caused by closed and open drains differs in that closed drains can draw the bowel wall into the side holes by negative pressure, whereas open drains may cause injury due to pressure necrosis[6]. Lai et al[7] reported drain migration through an anastomotic site after gastrectomy and lower esophagectomy for gastric cancer. The authors believe that it may be the result of migration through the site of an anastomotic leak. Wilmot et al[5] found the same observation. They suggested that surgical drain could migrate into the lumen in the region of the esophagogastric anastomosis at the site of a pre-existing anastomotic leak. Ravishankar et al[8] reported a case of spontaneous intraluminal drain migration in the jejunum at the site of lateral fistula from the Roux loop after total gastrectomy. They hypothesized that the collapse and fibrosis of associated abscess cavities may have facilitated the migration of the drains toward the bowel at the site of the leak.

Diagnosis of intraluminal migration can be difficult. Persistent drainage of intestinal contents is frequently indicative of an anastomotic leak. However, surgeons and radiologists should be aware that it may also signal the rare occurrence of intraluminal drain migration[5]. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of oral swallow radiographs for detecting EJAL are low[9-11]. In a prospective study of 66 patients, Lamb et al[12] demonstrated a sensitivity of 66.6% for routine contrast swallow in detecting EJAL, concluding that routine contrast swallow has no role following total gastrectomy. However, they acknowledged its value in providing information on the location and extent of leakage, as well as its utility in monitoring the progress of EJAL treatment[3,9]. CT scan has higher sensitivity and specificity than oral swallow radiographs[11,13]. It is easier to perform and allows for recognition of associated morbidities like abscess, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or pulmonary abnormalities. In our case, a CT scan with oral contrast may have identified the intraluminal migration of the drain earlier, potentially expediting diagnosis and shortening the patient's hospital stay. However, in the prospective study by Hogan et al[9], CT with oral contrast demonstrated equivalent sensitivity and superior specificity compared to contrast swallow in detecting EJAL.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is another diagnostic option that offers 100% sensitivity and specificity for definitive EJAL diagnosis[9]. Additionally, it can be employed therapeutically for EJAL management through the placement of self-expanding metallic stents, insertion of a nasojejunal feeding tube distal to the anastomotic dehiscence, or insertion of a drainage tube into the abscess cavity through the leak site[3]. Although there may be a reluctance to perform endoscopy during the early postoperative period due to concerns about disrupting healing tissue, studies have demonstrated that early endoscopy after gastric bypass surgery is both safe and feasible when performed by experienced endoscopists or surgeons[14].

There is no standardized diagnostic algorithm for EJAL or drain migration. Nevertheless, Makuuchi et al[3] proposed a diagnostic approach in which, if EJAL is suspected based on clinical signs, a CT scan should be performed initially, followed by a contrast swallow and/or endoscopy if indicated.

Intraluminal drain migration is a rare complication following gastric surgery but should be considered when persistent drainage occurs. If EJAL or drain migration is suspected, a CT scan should be the initial diagnostic step, followed by a contrast swallow or endoscopy if further evaluation is needed. Upon detection of intraluminal drain migration, conservative treatment involving drain removal is recommended to facilitate the healing of any associated anastomotic leaks.

| 1. | Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 3308] [Article Influence: 551.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Meyer HJ, Wilke H. Treatment strategies in gastric cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:698-705; quiz 706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Makuuchi R, Irino T, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Esophagojejunal anastomotic leakage following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2019;49:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carlomagno N, Santangelo ML, Grassia S, La Tessa C, Renda A. Intraluminal migration of a surgical drain. Report of a very rare complication and literature review. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84:219-223. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Wilmot AS, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Kucharczuk JC, Laufer I. Intraluminal migration of surgical drains after transhiatal esophagogastrectomy: radiographic findings and clinical relevance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:780-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nomura T, Shirai Y, Okamoto H, Hatakeyama K. Bowel perforation caused by silicone drains: a report of two cases. Surg Today. 1998;28:940-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lai PS, Lo C, Lin LW, Lee PC. Drain tube migration into the anastomotic site of an esophagojejunostomy for gastric small cell carcinoma: short report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ravishankar HR, Malik RA, Burnett H, Carlson GL. Migration of abdominal drains into the gastrointestinal tract may prevent spontaneous closure of enterocutaneous fistulas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:337-338. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hogan BA, Winter DC, Broe D, Broe P, Lee MJ. Prospective trial comparing contrast swallow, computed tomography and endoscopy to identify anastomotic leak following oesophagogastric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:767-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tonouchi H, Mohri Y, Tanaka K, Ohi M, Kobayashi M, Yamakado K, Kusunoki M. Diagnostic sensitivity of contrast swallow for leakage after gastric resection. World J Surg. 2007;31:128-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Clemente-Gutiérrez U, Rodríguez-Chong JG, Morales-Maza J, Rodríguez-Quintero JH, Sánchez-Morales G, Álvarez-Bautista FE, Cortés R, Medina-Franco H. Contrast-enhanced swallow study sensitivity for detecting esophagojejunostomy leakage. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2020;85:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lamb PJ, Griffin SM, Chandrashekar MV, Richardson DL, Karat D, Hayes N. Prospective study of routine contrast radiology after total gastrectomy. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1015-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Song P, Li J, Zhang Q, Gao S. Ultrathin endoscopy versus computed tomography in the detection of anastomotic leak in the early period after esophagectomy. Surg Oncol. 2020;32:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sharma G, Ardila-Gatas J, Boules M, Davis M, Villamere J, Rodriguez J, Brethauer SA, Ponsky J, Kroh M. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is safe and feasible in the early postoperative period after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgery. 2016;160:885-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/