Published online Mar 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i7.1313

Peer-review started: October 19, 2023

First decision: January 5, 2024

Revised: January 18, 2024

Accepted: February 4, 2024

Article in press: February 4, 2024

Published online: March 6, 2024

Processing time: 133 Days and 23 Hours

Refractory secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is a common complication observed in patients with end-stage renal disease and can result in ectopic calcifi

We present the case of a 31-year-old Asian female who was receiving maintenance hemodialysis because of lupus nephropathy. She developed SHPT, and an electrocardiogram revealed a first-degree atrioventricular block. Then, she underwent parathyroidectomy (PTX) with autotransplantation. Unfortunately, a few years later, she developed SHPT again, and an electrocardiogram revealed a CAVB. A few years after the second PTX surgery, the calcification of the left atrium and left ventricle improved, and her CAVB was reversed.

This case revealed that metastatic cardiac calcification can result in complete atrioventricular blockage. Following parathyroid surgery, calcification of the car

Core Tip: Refractory secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is known to cause bone pain, itching, and muscle weakness and can lead to an increased incidence of pathological fractures, metastatic calcification, and cardiovascular events. Metastatic calcification involving the heart valves and the conduction system, such as the mitral valve ring, can easily lead to arrhythmias, including atrioventricular block. The current case report describes a maintenance hemodialysis patient with refractory SHPT resulting in a complete atrioventricular block, which was reversed to a first-degree atrioventricular block after parathyroidectomy. The importance of optimizing parathyroid hormone management is further highlighted by comparing the pre- and postreversal indices.

- Citation: Xu SS, Hao LH, Guan YM. Reversal of complete atrioventricular block in dialysis patients following parathyroidectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(7): 1313-1319

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i7/1313.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i7.1313

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is a common complication observed in patients with end-stage renal disease and can result in ectopic calcification, significantly affecting quality of life and survival. Refractory SHPT is known to cause bone pain, itching, and muscle weakness and is associated with an increased incidence of pathological fractures[1], metastatic calcification, and cardiovascular events, all of which are significantly associated with increased mortality[2]. Metastatic calcification can involve the heart valves or the atrium, and calcification of the conduction system at the mitral valve ring can easily lead to arrhythmias, including atrioventricular block. An increase in intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) levels is associated with an increase in metastatic calcification and conduction block, underscoring the importance of timely management of hyperparathyroidism. This case report describes a maintenance hemodialysis patient with refractory SHPT resulting in a complete atrioventricular block (CAVB), which was eventually reversed to a first-degree atrioventricular block.

A 31-year-old female patient had been undergoing maintenance hemodialysis since 2009 and had bone pain and chest tightness for one year.

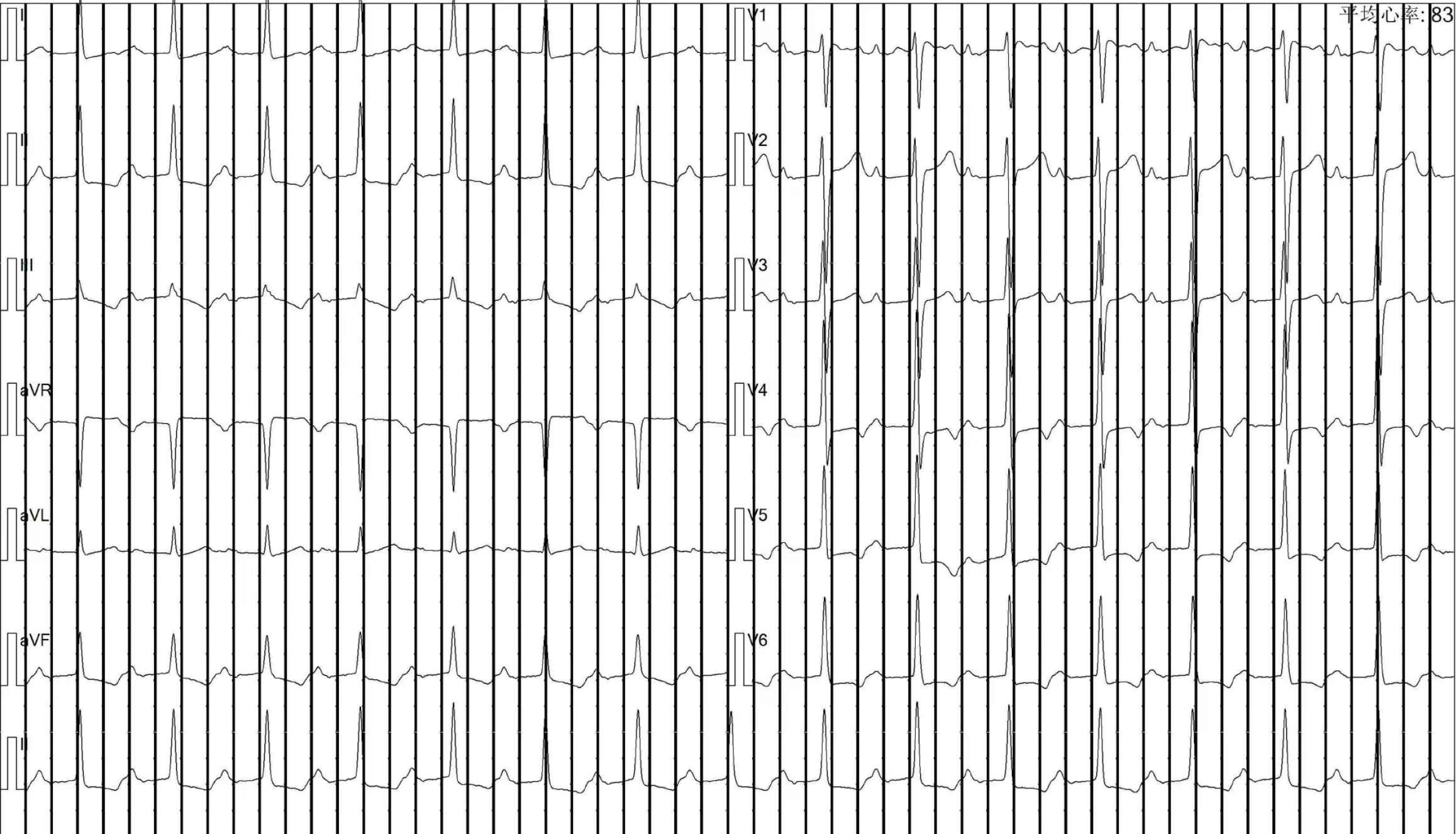

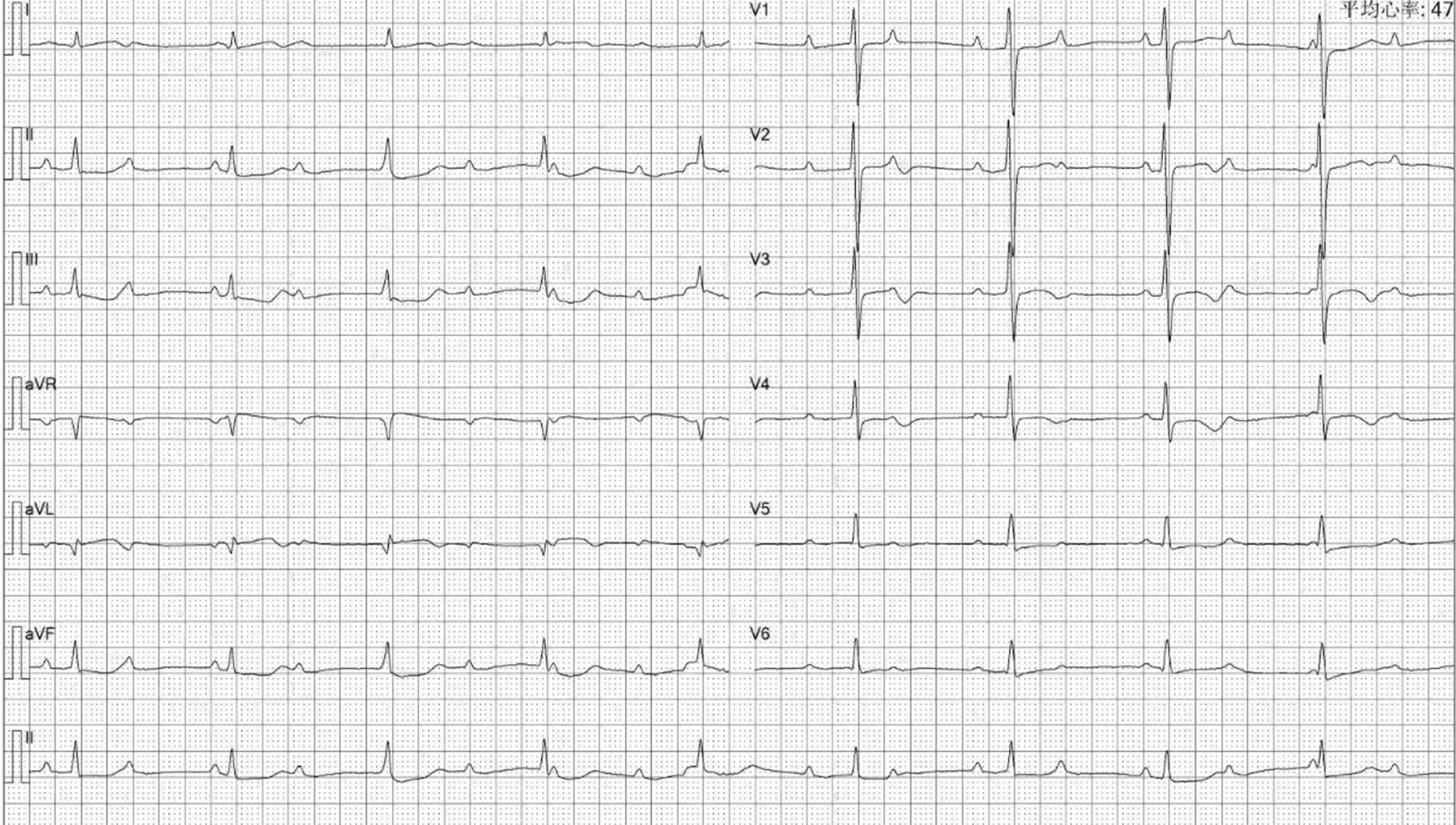

The patient had been undergoing maintenance hemodialysis at the department since 2009. In 2014, the patient developed SHPT with an iPTH level of 1400 pg/mL, for which calcitriol pulse therapy was applied. Over the next 5 years, the patient's iPTH levels increased progressively, leading to bone pain, skin itching, and difficult-to-correct hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia. In June 2018, a parathyroid B-ultrasound revealed parathyroid hyperplasia, and an electrocardiogram revealed a first-degree atrioventricular block (Figure 1). Total parathyroidectomy (PTX) with autotransplantation was performed, with four parathyroid glands completely removed during surgery and one resected parathyroid gland intramuscularly transplanted to the patient's right forearm. The iPTH levels decreased rapidly and were maintained at 40-80 ng/mL one month postsurgery and at 45-70 pg/mL on the side of the transplanted arm 3 months postsurgery. The patient's bone pain and skin itching were gradually relieved. However, 1.5 years later, the patient's iPTH level had risen again to 360-724 pg/mL, and the patient developed a serum calcium level of 2.37-2.86 mmol/L and a serum phosphorus level of 2.00-2.63 mmol/L. The patient was treated with intermittent use of paricalcitol and cinacalcet. The patient presented with bone pain, chest tightness and fatigue beginning in June 2020, and electrocardiography (ECG) revealed a third-degree or CAVB (Figure 2). The patient refused pacemaker therapy.

The patient had a medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephropathy. She had undergone regular hemodialysis for 12 years.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors or other genetic conditions.

The vital signs of the patient were as follows: body temperature, 36.5 °C; heart rate, 78/min; respiratory rate, 18/min; and blood pressure, 100/65 mmHg.

Her iPTH was > 5000 µmol/L, her serum calcium was 3.08 mmol/L, and her serum phosphorus was 3.47 mmol/L.

ECG revealed a third-degree or CAVB. Parathyroid nuclear scintigraphy (ECT)/CT parathyroid scintigraphy revealed a parathyroid adenoma. Color Doppler echocardiography showed calcification in the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve (Figure 3A). Chest CT showed extensive calcifications of the left atrium and left ventricle (Figure 4B and D).

The patient was diagnosed with SHPT and CAVB.

The patient underwent PTX again in March 2021. Postoperative pathology revealed hyperplastic parathyroid tissue.

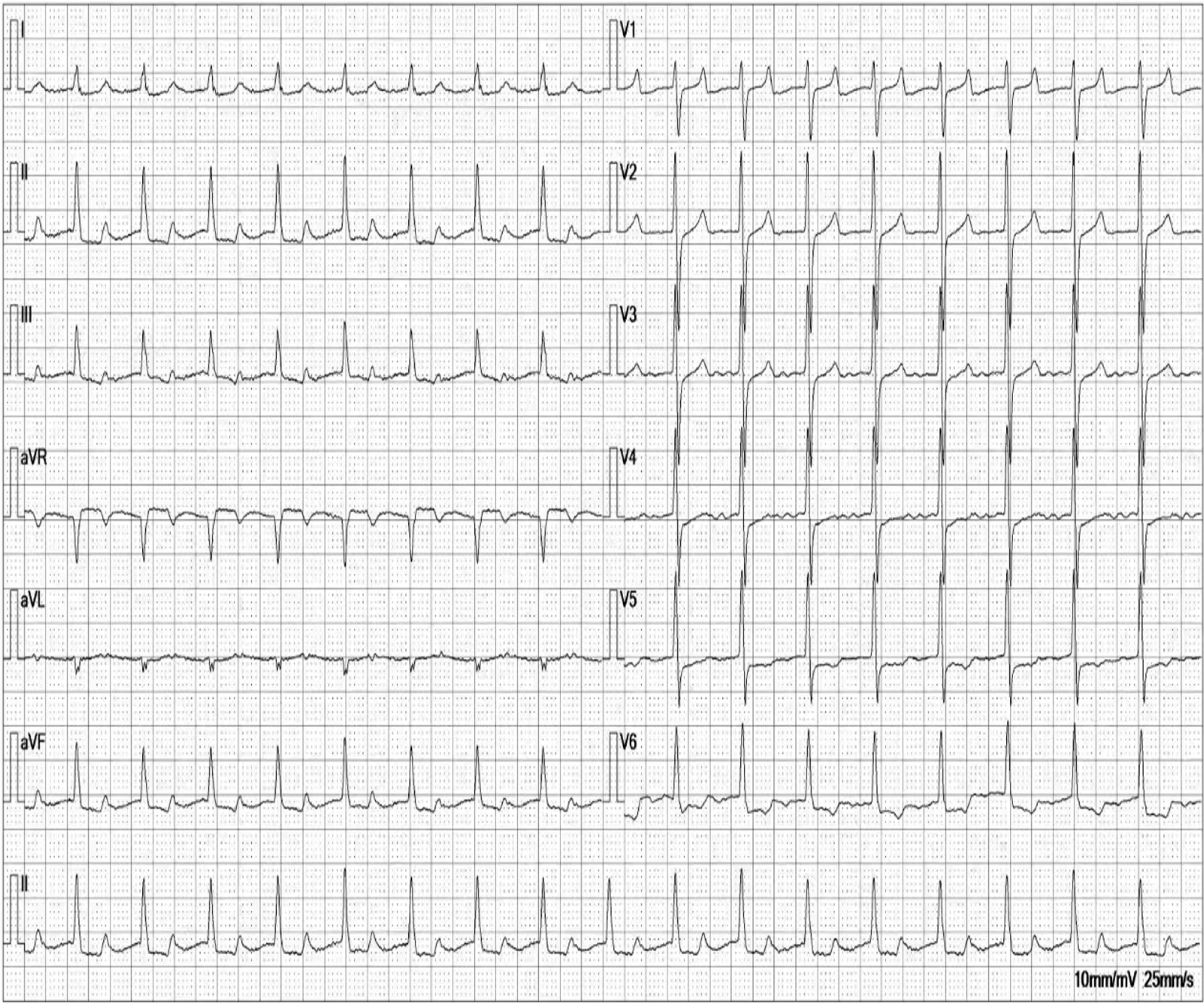

Following surgery, her iPTH level decreased to 51 ng/mL, and the patient developed hypocalcemia. One month postsurgery, the patient's iPTH levels were maintained at 54-110 ng/mL, her serum calcium levels were 1.75-2.35 mmol/L, and her blood phosphorus levels were 0.5-1.72 mmol/L. The patient's bone pain and itching significantly improved, but the patient still had a CAVB on the ECG. One year postsurgery, the iPTH levels were maintained between 50 and 100 ng/mL, without any significant discomfort. Chest CT showed improved calcification of the left atrium and left ventricle (Figure 4A and C), while the ECG showed a CAVB. Repeat ECG 2 years after surgery revealed that the patient's ECG was reversed to a first-degree atrioventricular block (Figure 5), and the calcification point in the posterior mitral lobe was reduced on cardiac ultrasound (Figure 3B). Unfortunately, the patient's EF was significantly lower than before (37%).

Bone mineral metabolism disorders are prevalent complications in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. High levels of calcium and phosphorus secondary to hyperparathyroidism can lead to ectopic calcification. Extensive myocardial calcification can cause refractory heart failure, while calcium deposits in the cardiac conduction system can lead to progressive arrhythmias, heart failure, and increased mortality[3]. Dysfunction of the cardiac conduction system due to calcification is infrequent but can lead to first-, second-, or third-degree atrioventricular block, affecting patient survival. The etiology of atrioventricular block can be functional or structural. Functional CAVB tends to be reversible and can be caused by factors such as autonomic disease, metabolic/endocrine disease, or drug-related disease. The reversibility of atrioventricular block secondary to bone mineral metabolism disorders in maintenance hemodialysis patients is still controversial, despite metabolic diseases being the primary cause.

Literature reports on the pathogenesis of atrioventricular block in hemodialysis patients are rare; according to the current knowledge, the etiology tends to be metastatic calcification, which includes calcification of the conduction system and the mitral valve ring. Notably, an early case report by Dreher et al[4] in 1975 demonstrated complete recovery of first-degree atrioventricular block following complete PTX in an end-stage hemodialysis patient with cardiac metastatic calcification. Similarly, Fujimoto et al[5] reported the case of a hemodialysis patient with third-degree SHPT and metastatic calcification resulting in atrioventricular block who died with extensive metastases despite hospitalization. Anam et al[3] recently described a case of CAVB secondary to severe hyperparathyroidism in a dialysis patient, highlighting the importance of suspecting metastatic cardiac calcification in cases of end-stage renal failure with elevated parathyroid hormone levels and concomitant first-degree atrioventricular conduction block and mitral annular calcification. To prevent progression of the atrioventricular block, measures should be taken to normalize parathyroid hormone, calcium, and phosphorus levels, possibly through exploration or removal of the parathyroid glands if the blockage worsens. In nonhemodialysis patients, primary hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia can also cause atrioventricular blockage due to calcium deposition, leading to atrioventricular node degeneration, as reported by Vosnakidis et al[6] in a case study involving dizziness, headache, and paroxysmal 2:1 atrioventricular block. Therefore, both primary and SHPT may lead to hypercalcemia and ultimately metastatic cardiac calcification, which is considered the primary mechanism underlying atrioventricular blockage.

Metastatic calcification in dialysis patients is a multifactorial condition, and its improvement is closely related to PTX. Uremic tumor calcinosis, corneal and conjunctival calcification, and arterial calcification are a few examples of conditions that are linked to this surgical intervention. Li et al[7] reported complete relief of calcification in a patient with uremic tumor calcinosis two months after PTX. Another study confirmed that PTX in dialysis patients can rectify calcium and phosphorus metabolism disorders, reduce arterial calcification, and improve arteriosclerosis[8]. Additionally, a 2008 case report suggested that SHPT plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of tumor calcinosis in patients on hemodialysis[9]. Pessoa et al[10] reported the recovery of a patient with conjunctival and corneal calcification after PTX. In this case, the CAVB was caused by metastatic calcification of the heart, including metastatic calcification of the left atrium, left ventricle and mitral valve. The patient’s atrioventricular block was reversed to a first-degree atrioventricular block 2 years after PTX surgery, and re-examination via chest CT and color ultrasound showed that the left atrial and left ventricular calcification was significantly better than before. Cardiac ultrasound showed that the calcification point in the posterior mitral lobe was reduced compared with that in the front; therefore, we considered that the reversal of CAVB in this patient was related to the improvement of metastatic calcification after PTX surgery. Since this patient refused to undergo pacemaker implantation, her cardiac function was reduced, and the PR interval was prolonged, although the CAVB block was reversed 2 years after the operation. Therefore, the author believes that in hemodialysis patients, the iPTH level should be optimized in the early stage, and patients should undergo relevant surgical treatment in a timely manner to improve their general condition.

This case reveals that metastatic cardiac calcification can result in complete atrioventricular blockage. Following parathyroid surgery, calcification of the cardiac conduction system improved, leading to reversal of the atrioventricular block. However, because cardiac function is significantly lower in these patients than before surgery, it is important for dialysis patients to receive optimized iPTH therapy and pay attention to calcification metastasis.

The authors thank the patient for participating in this study.

| 1. | Isaksson E, Ivarsson K, Akaberi S, Muth A, Sterner G, Karl-Göran P, Clyne N, Almquist M. The Effect of Parathyroidectomy on Risk of Hip Fracture in Secondary Hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg. 2017;41:2304-2311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, Ofsthun N, Lowrie EG, Chertow GM. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2208-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1878] [Cited by in RCA: 1902] [Article Influence: 86.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anam R, Tellez M, Lozier M, Waheed A, Collado JE. The Harder the Heart, the Harder It Breaks: A Case of Complete Atrioventricular Block Secondary to Tertiary Hyperparathyroidism. Cureus. 2021;13:e13276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dreher W, Shelp W. Atrioventricular block in a long-term dialysis patient. Reversal after parathyroidectomy. JAMA. 1975;234:954-955. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Fujimoto S, Hisanaga S, Yamatomo Y, Tanaka K, Hayashi T, Sumiyoshi A. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism associated with metastatic cardiac calcification in a haemodialyzed patient. Int Urol Nephrol. 1991;23:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vosnakidis A, Polymeropoulos K, Zarogoulidis P, Zarifis I. Atrioventricular nodal dysfunction secondary to hyperparathyroidism. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:E90-E92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li SY, Chuang CL. Rapid resolution of uremic tumoral calcinosis after parathyroidectomy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:e97-e98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gao Z, Li X, Miao J, Lun L. Impacts of parathyroidectomy on calcium and phosphorus metabolism disorder, arterial calcification and arterial stiffness in haemodialysis patients. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:6-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Younes M, Belghali S, Zrour-Hassen S, Béjia I, Touzi M, Bergaoui N. Complete reversal of tumoral calcinosis after subtotal parathyroidectomy in a hemodialysis patient. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:606-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pessoa MBCN, Santo RM, De Deus AA, Duque EJ, Rochitte CE, Moyses RMA, Elias RM. Corneal and Conjunctival Calcification in a Dialysis Patient Reversed by Parathyroidectomy. Blood Purif. 2021;50:254-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Juneja D, India S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM