Published online Jan 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i3.551

Peer-review started: April 28, 2023

First decision: July 27, 2023

Revised: August 8, 2023

Accepted: August 17, 2023

Article in press: August 17, 2023

Published online: January 26, 2024

Processing time: 264 Days and 13.3 Hours

Epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (EMPNST) of the bladder is a rare entity with devastating features. These tumors are thought to originate from malignant transformation of pre-existing schwannomas of pelvic autonomic nerve plexuses, and unlike the conventional malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), are not associated with neurofibromatosis. The tumor has dis

In this case report, we present the detailed clinical course of a 71-year-old patient with EMPNST of the bladder alongside a literature review.

During the management of EMPNST cases, offering aggressive treatment moda

Core Tip: In this case report, we describe a patient diagnosed with epithelioid variant of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the bladder wall after thorough pathologic examination. The case is noteworthy, as it is the second reported case that provides information regarding the patient’s prognosis.

- Citation: Ozden SB, Simsekoglu MF, Sertbudak I, Demirdag C, Gurses I. Epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the bladder and concomitant urothelial carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(3): 551-559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i3/551.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i3.551

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) are sarcomas that originate from peripheral nerves from a pre-existing benign nerve sheath tumor or seldomly from a neurofibroma in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) patients[1]. In the absence of these settings, particularly in sporadic de novo or radiotherapy-associated tumors, the diagnosis is based on the histological and immunohistochemical features suggesting Schwannian differentiation[2]. The incidence of the neoplasm is thought to be 0.001 percent in the general population[3]. Epithelioid variant of the MPNST (EMPNST) is a rare subtype of MPNST with distinctive morphological, immunohistochemical and molecular changes[4]. Among the MPNST subtypes, EMPNST occurs in approximately 5% of cases and has only been reported as case series[4]. Because of its rarity, there are no high-volume studies that clearly report the disease characteristics. Although it is hard to make solid statements regarding the course of the disease, there are strong clinical opinions supported by observation. In contrast to conventional MPNST, EMPNST is not associated with neurofibromatosis. It is thought to originate from the malignant transformation of pre-existing epithelioid schwannomas of deep neural tissues with loss of genes like SMARCB/INI1[5,6]. EMPNSTs rarely have genetic alterations in the neurofibromin (NF1), p16/p15 (CDKN2A/CDKN2B), and PRC2 pathways. EMPNST typically shows diffuse strong staining with S100 and SOX10 in contrast to conventional MPNST[5,7]. SMARCB1 gene inactivation resulting in SMARCB1 loss by immunohistochemistry is observed in approximately 75% of cases[6]. In addition, EMPNSTs tend to be more aggressive and have higher mortality[5,7].

The first case published on this specific neoplasm was described to have a non-neoplastic bladder mucosa and occurred as an isolated EMPNST[8]. Our case is unique, as it is the first case that presents with a synchronous urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and the epithelioid variant of MPNST in the literature. It is also the second EMPNST case reported originating from the bladder wall.

A 71-year-old elderly patient presenting with 1 mo of painless intermittent macroscopic hematuria with a history of the frequency with intermittency was admitted to our outpatient clinic. The patient was an ex-smoker (50 pack/year) and had diabetes and chronic kidney disease. He was on routine surveillance for an incidental tubulo-villous adenoma on the sigmoid colon by our general surgery department. The patient had no history of a previous radiotherapy or neuro

On physical examination, there was no remarkable finding during the inspection. No skin lesions (neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots) were noted. On digital rectal examination, prostate was found to be moderately enlarged with no stiffness or irregularities. Blood samples were collected at admission; the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (2.46 ng/mL) was within normal range (0-4 ng/mL), while the levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (69 mg/dL; normal range: 10-50 mg/dL) and creatinine (1.30 mg/dL; normal range: 0.3-1.1 mg/dL) were elevated. The collected urine sample revealed micro

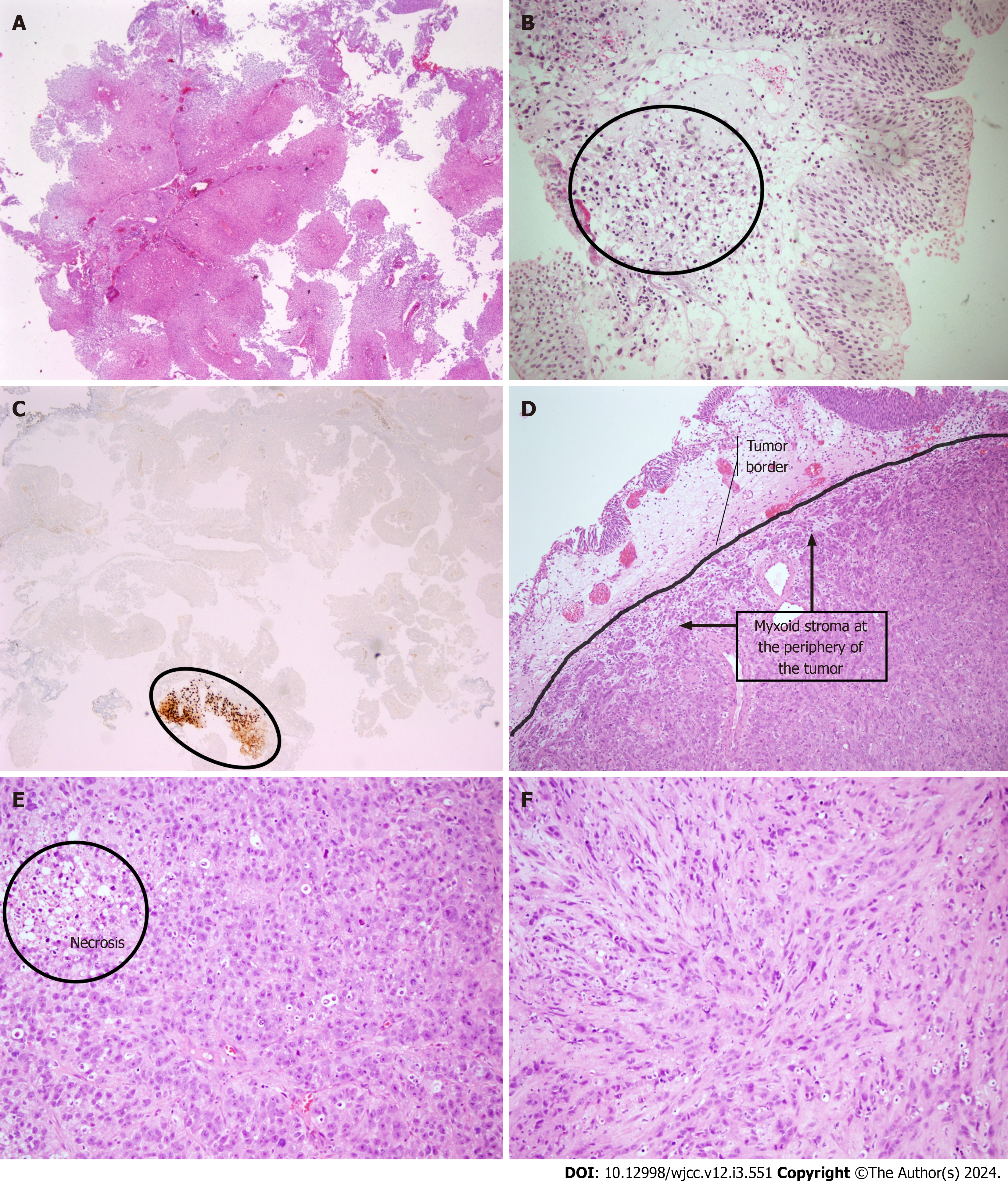

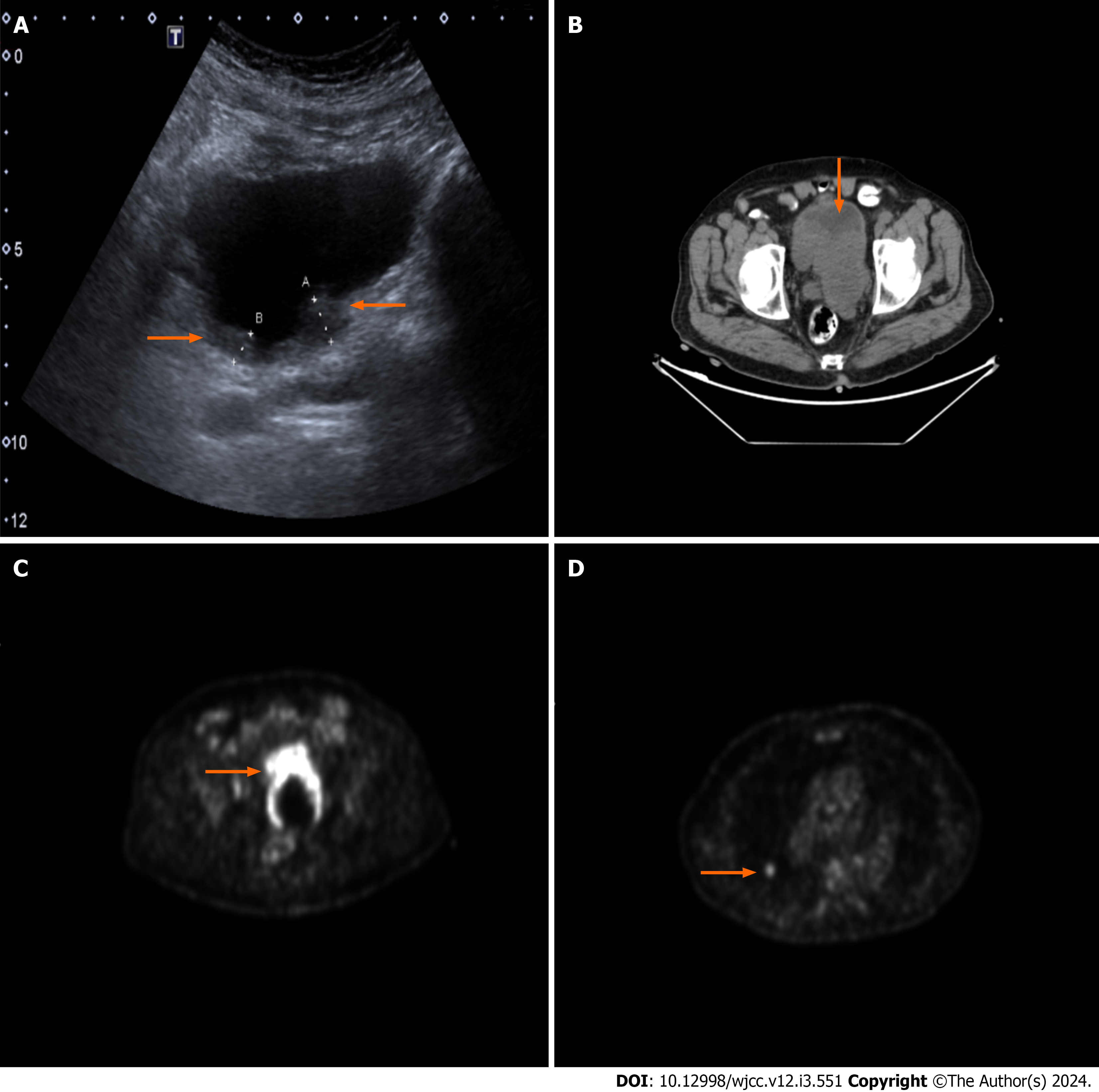

A urinary ultrasound scan was conducted revealing a diverticulum with a 45 mm × 35 mm diameter harboring a suspicious papillary projection with a dimension of 30 mm × 20 mm on the posterior bladder wall. A prompt cystoscopy was performed revealing one papillary lesion with a 30 mm × 30 mm diameter on the prementioned diverticulum wall and another 10 mm × 10 mm lesion on the right posterolateral bladder wall. Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) was performed on both lesions. Because one of the lesions was located on the diverticulum wall, the resection was performed superficially. On pathological evaluation, both resection materials were found to be non-invasive low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma (Figure 1).

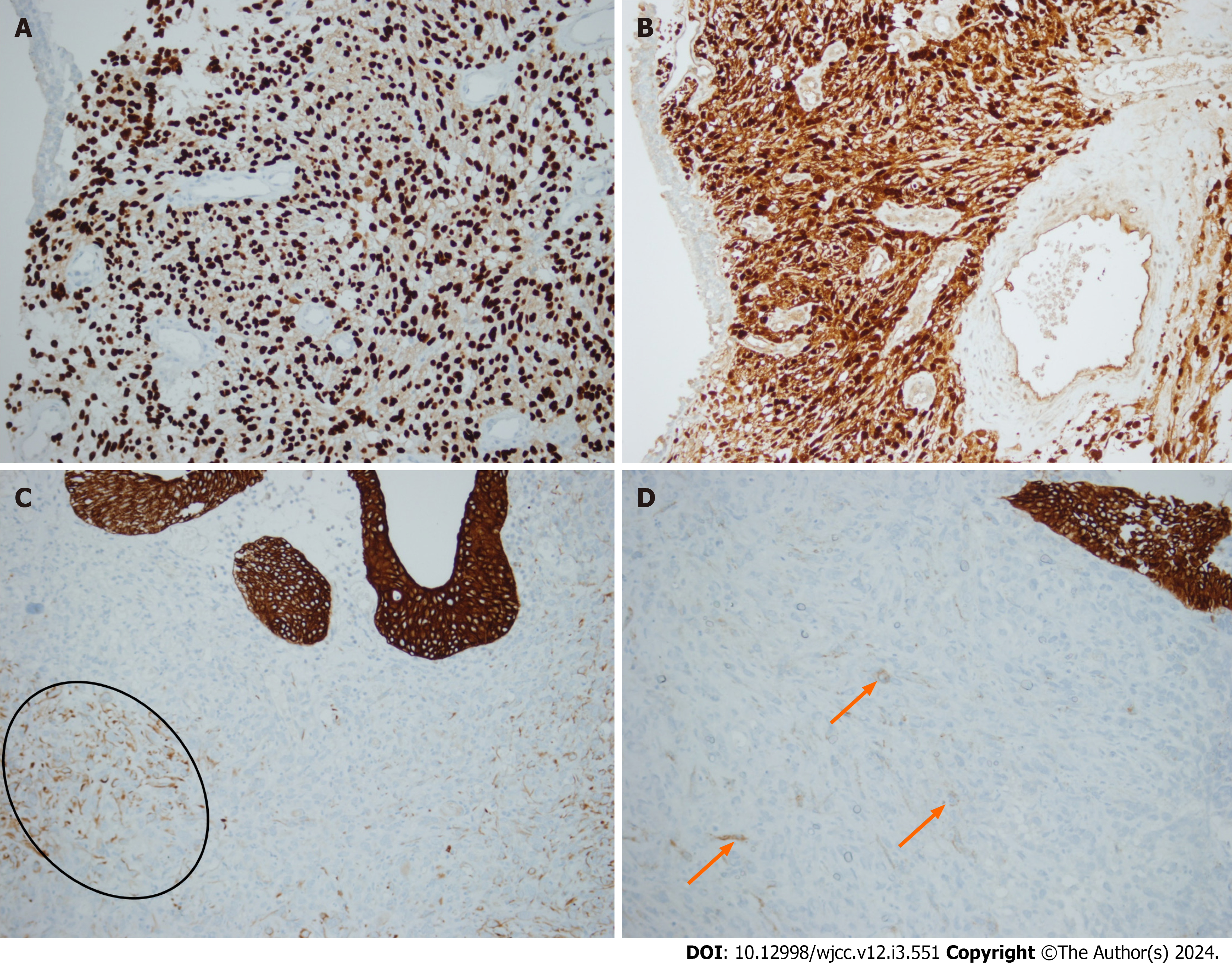

After the initial procedure, the patient’s hematuria regressed. The patient then underwent a routine control cystoscopy session 3 mo after the primary resection. Suspicious papillary projections on both old resection sites and in proximity to the right ureteric orifice were identified. Complete resection was performed with respective deep resection biopsies. On pathological examination, both lesions had non-invasive low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. The tissue sample resected near the right ureteric orifice was found to have atypical mesenchymal cell infiltration in the lamina propria. The cells stained positive with S100, SOX10 and vimentin, suggesting that the cells had a neural origin (Figure 1). The blood sample was sent to our Genetics department for NF-1 mutation analysis, but it was not detected on fluorescent in situ hybridization.

A re-TURBT was planned 2 wk later for the proper reassessment of the tumor. However, due to lack of adherence by the patient, it was performed 4 mo later. The patient had weight loss and intermittent hematuria with clot passage during the time span. On cystoscopic examination, suspicious bladder wall irregularities including diffuse solid lesions protruding into the bladder lumen were observed in a 5 cm × 5 cm area extending from one lateral wall to the other, including the bladder trigone. An incomplete resection could have been performed due to the tumor size. Microscopically, the tumor comprised a relatively uniform but clearly atypical population of epithelioid cells and a smaller pro

A full body fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography (FDG-PET CT) scan was per

The patient was discussed in a multidisciplinary uro-oncology meeting with the participation of urology, oncology, pathology, and radiation oncology departments. It had been decided to perform a radical cystoprostatectomy and ex

Through the pathologic examination of the cystoprostatectomy specimen, full-thickness infiltrating EMPNST into the bladder wall was identified. There was also a heterologous component (mature bone) in the focal area within the tumor. No other peripheral nerve sheath-associated tumor types (schwannoma, neurofibroma or perineuroma) were noted. In addition, acinar adenocarcinoma (Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6) was detected incidentally in the prostate. EMPNST metastases were detected in 2 of 11 right pelvic lymph nodes removed. The number of bilaterally excised lymph nodes was 18.

An intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed 3 mo after the cystectomy. The lesion located on the apical portion of the right lung was found to be increased in diameter (13 mm × 14 mm) and another nodular lesion with contrast uptake was added to the inferior lobe of the right lung. The patient could not receive any additional systemic therapy due to frailty. The patient passed away 4 mo after the cystectomy and 12 mo after the initial diagnosis due to emerging type 1 respiratory failure causing cardiac arrest after intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

Tubulovillous adenoma of sigmoid colon was detected prior to endourological intervention.

Patient has known diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

The patient was an ex-smoker (50 pack/year). No remarkable family history of chronic illness was recorded.

On physical examination, there was no remarkable finding during the inspection. No skin lesions (neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots) were noted. On digital rectal examination, the prostate was moderately enlarged with no stiffness or irregularities.

Blood samples were collected at admission. The PSA level was within normal range 2.46 ng/mL (0 to 4), and BUN and creatinine levels were elevated (69 mg/dL and 1.30 mg/dL, respectively). The collected urine sample indicated mi

A urinary ultrasound scan was conducted revealing a diverticulum with a 45 mm × 35 mm diameter harboring a sus

A full body FDG-PET CT scan was performed to rule out distant metastases and for local staging. On abdominopelvic cross-sectional images, an intrapelvic mass was bordering the posterior bladder wall and causing compression and distortion of pelvic structures. No distinctive border could be identified between the mass and the bladder wall. Increased FDG uptake on both the right external iliac and right common iliac lymph nodes was noted. An isolated paracaval lymph node just above the right iliac bifurcation had increased FDG uptake. On cross-sectional thoracal images, a nodular lesion on the right upper lobe of the lung with a 14 mm × 13 mm diameter was observed. The lesion also had nuclear material uptake, making it a candidate for metastases of the primary lesion.

It was decided to perform a radical cystoprostatectomy and extended lymph node resection for local disease control.

The pathological diagnosis was in concordance with high-grade EMPNST of the bladder.

The patient underwent radical cystoprostatectomy with ileal loop repair and bilateral ilioinguinal lymph node dissection.

The patient passed away 4 mo after the cystectomy and 12 mo after the initial diagnosis due to emerging type 1 respiratory failure causing cardiac arrest after ICU admission.

Mesenchymal tumors comprise 0.04% of all malignant tumors of the whole urinary system[10]. Bladder-originating MPNST is a lesser-known entity that originates from pelvic autonomic nerve plexuses. MPNST is only occasionally documented in the case reports in the literature, making the process of diagnosis and treatment harder due to a lack of evidence-based data. Most reported patients are diagnosed with NF-1 disease and are below the age of 40. Published cases mostly presented with hematuria, suprapubic mass, and urinary retention. Most cases were not distinguished from urothelial carcinoma during cystoscopy and transurethral resection[8,11,12].

Even though EMPNST has been known since 1957, EMPNST alone only constitutes 5% of all MPNSTs. Due to its rarity, information regarding the clinical presentation and prognosis remains the same. Yet, the understanding of the tumor's histopathologic features has evolved through the years by the refinement of histopathological diagnostic tools[4-6]. EMPNST of the bladder alone is a much rarer entity with aggressive features and a very poor prognosis, making it hard to be studied under prospective randomized clinical trials. The two known risk factors for conventional MPNSTs are radiation exposure and neurofibromatosis type 1[3]. Though in a comprehensive case series, no EMPNST patients had neurofibromatosis and some had benign schwannoma areas in resected tumor samples, suggesting that the tumor originates from a benign neoplasm in contrast to conventional MPNSTs[4]. They are thought to originate from malignant transformation of pre-existing epithelioid schwannomas of the deep neural tissues.

It is challenging to differentiate EMPNST from urothelial carcinoma by clinical evaluation. Ultrasonography, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging cannot differentiate EMPNST from urothelial carcinoma. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the pathology in detail with appropriate methods[8,13].

Typically, EMPNSTs are composed of spindle cells growing in a haphazard manner consisting of interlacing sheets and nodules accompanied by atypical round polygonal ovoid cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm[14]. More than 50% of tumor cells should be in polygonal morphology. In addition to these features, they present with interstitial infiltration of inflammatory cells namely mononuclear cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils[4].

This entity has a distinct immunophenotypic characteristic. Unlike conventional MPNSTs, EMPNSTs show strong and diffuse staining for S100 and SOX10, alongside the absence of melanoma markers. They may also be positive for keratin and retain expression of H3K27me3[4,5,8]. Molecular distinction of EMPNSTs from conventional MPNSTs can be further elaborated. SMARCB1 gene inactivation resulting in SMARCB1 loss by immunohistochemistry is observed in approximately 75% of cases[6]. They rarely have genetic alterations in the neurofibromin (NF1), p16/p15 (CDKN2A/CDKN2B), and PRC2 pathways[4,7]. In addition, they tend to be more aggressive and have higher mortality than MPNSTs[4-6].

Sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, epithelioid angiosarcoma, melanoma and perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) fall into pathological differential diagnosis of this neoplasm. The first tumor to be considered in the differential diagnosis of our case was sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma. No macroscopic or microscopic relationship was identified between the urothelial tumor in the bladder mucosa and the tumor in the bladder wall. Furthermore, the mucosal tumor consisted entirely of non-invasive low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma; no high grade foci or lamina propria invasion was observed. The EMPNST in the bladder wall was diffusely positive for SOX10 and S100, while urothelial tumors stain negative for these markers. Epithelial markers (EMA, CK7) were focally positive, in contrast to anticipated diffuse staining in urothelial carcinomas. GATA3 was also negative in the tumor, whereas urothelial car

The patient has no history of melanoma, and no in situ melanocytic lesion in the bladder was observed. Some nuclei were wavy in the spindle areas of the tumor and no pigment (melanin) was detected. In melanoma, positivity of epithelial markers is not expected, whereas focal positivity can be seen in EMPNST, as in our case. In addition to morphological findings, leiomyosarcoma and angiosarcoma were ruled out due to negative muscle and vessel markers. PEComas are composed of epithelioid and/or spindle cells with clear to eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. Epithelioid cells are arranged in dyscohesive nests surrounded by delicate thin-walled vessels and/or in sheets, whereas spindle cells often form fascicles. Radial/perivascular distribution of tumor cells is a valuable finding. Conventional PEComas express HMB45, mela-A and smooth muscle markers with variable intensity and extent. HMB45 is a more sensitive marker, being positive in nearly all PEComas, whereas melan-A is a more specific marker, being positive in at least half of the tumors[15]. Melanocytic markers were exclusively negative in the tumor within the bladder wall.

Primary treatment modality for conventional MPNSTs is surgical resection if no gross solid organ metastases are present. Adjuvant radiotherapy can be given to provide local disease control after resection. Unfortunately, the distant metastases are almost always present or may become evident within 2 mo after initial diagnosis. Although the effectiveness is still controversial, patients with unresectable tumors on the trunk or extremities may benefit from anthracycline regimens plus doxorobucin, ifosfamide, etoposide regimens[16,17]. Furthermore, since the sarcoma deploys from a neural crest originated stem cell, it may express BRAFv600E mutations, which may respond to targeted systemic therapy with vemurafenib[18,19]. There are some continuing molecular and in vitro cell culture studies to identify tumor vulnerability in advance for a potential targeted therapy[19-21].

For the MPNST of the bladder, the data regarding the disease stems from cases reported at different clinics around the globe. There is no high-volume study covering patient demographics, prognosis, or clinical data, such as overall survival or disease-free survival after undergoing different treatment modalities.

Nevertheless, the disease has mostly been recorded in patients younger than the fourth decade of their lives. The majority of patients have type 1 neurofibromatosis with the exception of a few sporadic cases[14]. The youngest patient reported in the literature had neurofibromatosis type 1 disease and was 9-years-old at the time of diagnosis. The patient underwent cystectomy and was treated with systemic therapy[22]. The disease may present with painless hematuria, abdominal mass, weight loss or nonspecific irritative urinary symptoms. No clinically significant tumor-specific centricity has been noted in the literature, and the neoplasm may arise from the trigone, dome, or the lateral walls of the bladder. Although long-term follow ups are not disclosed in case reports, it is known that the prognosis is poor and that the disease is generally at an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis[8,9,11,23,24]. Even though there is a single reported case cured with transurethral resection of the tumor, the patient’s long-term follow-up is unknown. Moreover, the epithelial variant of the tumor has only been reported once in the literature, and very little is known regarding the prognosis of the reported patient[8]. Our case is unique because the patient presents with a synchronous EPMNST and urothelial car

Our presented case is unique; it is the first case that presents with a synchronous urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and epithelioid variant of MPNST. It is the second reported case of bladder EMPNST.

In conclusion, during the management of EMPNST cases, offering aggressive treatment modalities such as radical cystectomy to the patient is appropriate for the chance of containing the disease, regardless of tumor stage and the extent of local disease at the initial diagnosis. There is no oncological consensus or evidence-based data on the use of systemic therapy for MPNST originating from the urogenital system. It is not known whether performing radical surgery has any effect on prognosis and it should be further investigated on studies with higher patient volume.

| 1. | Perrin RG, Guha A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15:203-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, Kim A, Lazar AJ, Quezado MM, Reilly KM, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Stewart DR, Viskochil D, Widemann B, Perry A. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Moes G, Kline DG. A series of 397 peripheral neural sheath tumors: 30-year experience at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:246-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Laskin WB, Weiss SW, Bratthauer GL. Epithelioid variant of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (malignant epithelioid schwannoma). Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1136-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee W, Teckie S, Wiesner T, Ran L, Prieto Granada CN, Lin M, Zhu S, Cao Z, Liang Y, Sboner A, Tap WD, Fletcher JA, Huberman KH, Qin LX, Viale A, Singer S, Zheng D, Berger MF, Chen Y, Antonescu CR, Chi P. PRC2 is recurrently inactivated through EED or SUZ12 loss in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1227-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schaefer IM, Dong F, Garcia EP, Fletcher CDM, Jo VY. Recurrent SMARCB1 Inactivation in Epithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:835-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jo VY, Fletcher CDM. SMARCB1/INI1 Loss in Epithelioid Schwannoma: A Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study of 65 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:1013-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eltoum IA, Moore RJ 3rd, Cook W, Crowe DR, Rodgers WH, Siegal GP. Epithelioid variant of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (malignant schwannoma) of the urinary bladder. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1999;3:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Neuville A, Chibon F, Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: from histological to molecular assessment. Pathology. 2014;46:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D, Snyder ME, Antonescu C, Brennan MF, Russo P. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: the 25-year Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Urol. 2006;176:2033-8; discussion 2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Petracco G, Patriarca C, Spasciani R, Parafioriti A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the bladder A case report. Pathologica. 2019;111:365-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Karatzoglou P, Karagiannidis A, Kountouras J, Christofiridis CV, Karavalaki M, Zavos C, Gavalas E, Patsiaoura K, Vougiouklis N. Von Recklinghausen's disease associated with malignant peripheral nerve sheath thmor presenting with constipation and urinary retention: a case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:3107-3113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jiwani S, Gokden M, Lindberg M, Ali S, Jeffus S. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: A case report and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng L, MacLennan GT, Bostwick DG. Urologic Surgical Pathology. Fourth edition. Elsevier; 2020. (pp 300-302). [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Hamza A, Guo CC. Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor of the Urinary Bladder: A Systematic Review. Int J Surg Pathol. 2020;28:393-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kroep JR, Ouali M, Gelderblom H, Le Cesne A, Dekker TJA, Van Glabbeke M, Hogendoorn PCW, Hohenberger P. First-line chemotherapy for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) versus other histological soft tissue sarcoma subtypes and as a prognostic factor for MPNST: an EORTC soft tissue and bone sarcoma group study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bradford D, Kim A. Current treatment options for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2015;16:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rekhi B, Kosemehmetoglu K, Tezel GG, Dervisoglu S. Clinicopathologic features and immunohistochemical spectrum of 11 cases of epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, including INI1/SMARCB1 results and BRAF V600E analysis. APMIS. 2017;125:679-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang K, Du J, Shi D, Ji F, Ji Y, Pan J, Lv F, Zhang Y, Zhang J. Knockdown of MSI2 inhibits metastasis by interacting with caveolin-1 and inhibiting its ubiquitylation in human NF1-MPNST cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Terribas E, Fernández M, Mazuelas H, Fernández-Rodríguez J, Biayna J, Blanco I, Bernal G, Ramos-Oliver I, Thomas C, Guha R, Zhang X, Gel B, Romagosa C, Ferrer M, Lázaro C, Serra E. KIF11 and KIF15 mitotic kinesins are potential therapeutic vulnerabilities for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2:i62-i74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gampala S, Shah F, Zhang C, Rhodes SD, Babb O, Grimard M, Wireman RS, Rad E, Calver B, Bai RY, Staedtke V, Hulsey EL, Saadatzadeh MR, Pollok KE, Tong Y, Smith AE, Clapp DW, Tee AR, Kelley MR, Fishel ML. Exploring transcriptional regulators Ref-1 and STAT3 as therapeutic targets in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1566-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bouty A, Dobremez E, Harper L, Harambat J, Bouteiller C, Zaghet B, Wolkenstein P, Ducassou S, Lefevre Y. Bladder Dysfunction in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type I: Report of Four Cases and Review of the Literature. Urol Int. 2018;100:339-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Somatilaka BN, Sadek A, McKay RM, Le LQ. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: models, biology, and translation. Oncogene. 2022;41:2405-2421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | O'Brien J, Aherne S, Buckley O, Daly P, Torreggiani WC. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour of the bladder associated with neurofibromatosis I. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2:637-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: European Association of Urology, No. 110323.

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alkhatib AJ, Jordan S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH