Published online Oct 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i28.6132

Revised: June 5, 2024

Accepted: June 26, 2024

Published online: October 6, 2024

Processing time: 162 Days and 8.5 Hours

In this editorial we comment on the article by Huffaker et al, published in the current issue of the World Journal of Clinical Cases. Cardiac masses encompass a broad range of lesions, potentially involving any cardiac structure, and they can be either neoplastic or non-neoplastic. Primitive cardiac tumors are rare, while metastases and pseudotumors are relatively common. Cardiac masses frequently pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Multimodality imaging is fundamental for differential diagnosis, treatment, and surgical planning. In particular cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) is currently the gold standard for noninvasive tissue characterization. CMR allows evaluation of the relationship between the tumor and adjacent structures, detection of the degree of infiltration or expansion of the mass, and prediction of the possible malignancy of a mass with a high accuracy. Different flow charts of diagnostic work-up have been proposed, based on clinical, laboratory and imaging findings, with the aim of helping physicians approach the problem in a pragmatic way (“thinking inside the box”). However, the clinical complexity of cancer patients, in particular those with rare syndromes, requires a multidisciplinary approach and an open mind to go beyond flow charts and diagnostic algorithms, in other words the ability to “think outside the box”.

Core Tip: Cardiac masses pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Multimodality imaging is fundamental for diagnosis, treatment, and surgical planning. Different flow charts of diagnostic work-up have been proposed to help physicians approach the problem in a pragmatic way (“thinking inside the box”). However, the clinical complexity of cancer patients, in particular those with rare syndromes, requires an open mind to go beyond diagnostic algorithms, and the ability to “think outside the box.”

- Citation: De Maria E. Approach to cardiac masses: Thinking inside and outside the box. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(28): 6132-6136

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i28/6132.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i28.6132

Cardiac masses pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Multimodality imaging is fundamental for diagnosis, treatment and surgical planning. Different flow charts of diagnostic work-up have been proposed to help physicians approach the problem in a pragmatic way (“thinking inside the box”). However, the clinical complexity of cancer patients, in particular those with rare syndromes, requires an open mind to go beyond diagnostic algorithms, and the ability to “think outside the box”.

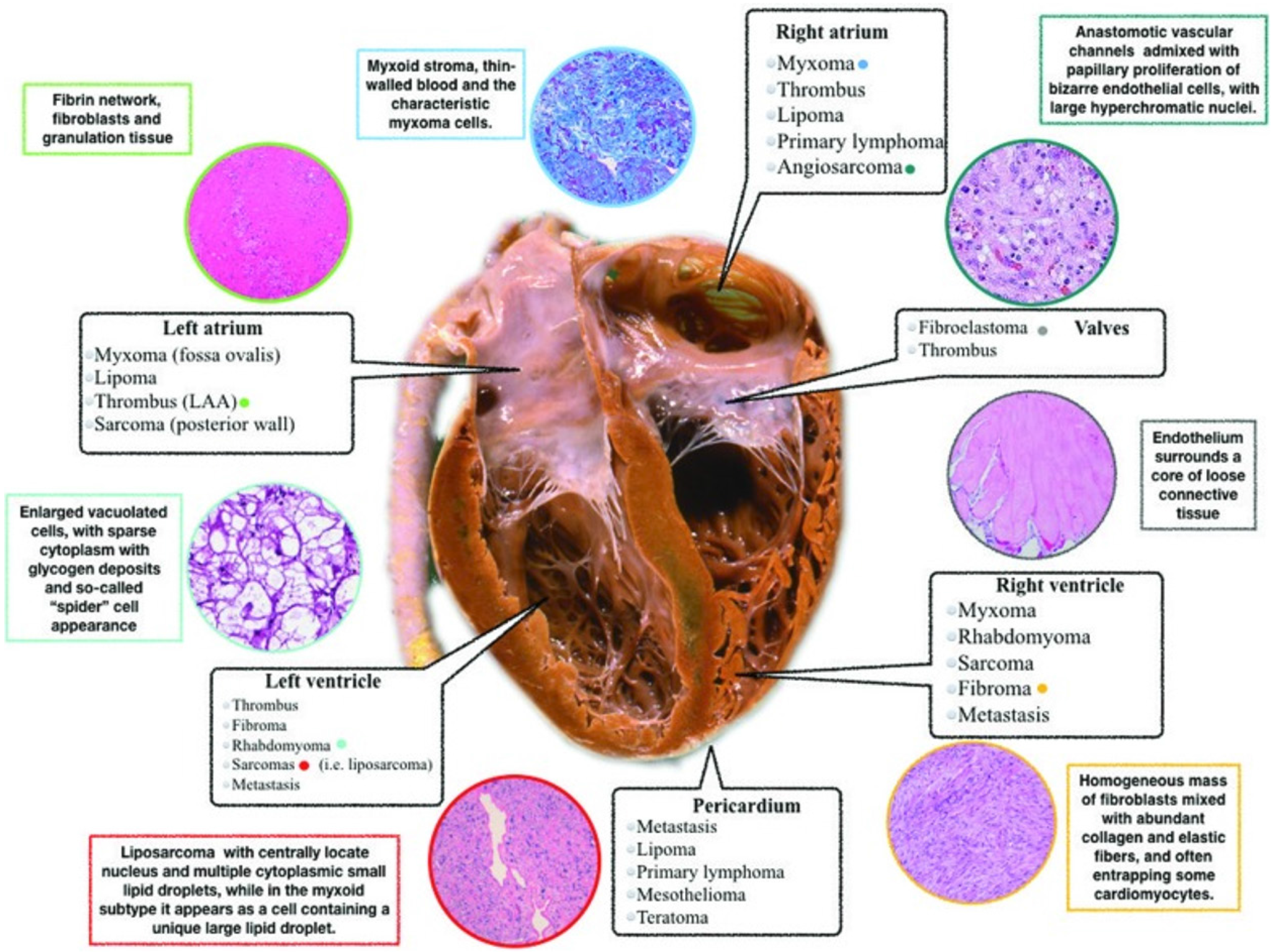

Cardiac masses encompass a broad range of lesions, potentially involving any cardiac structure, and they can be either neoplastic (benign or malignant primary cardiac tumors and secondary cardiac tumors/metastases) or non-neoplastic (thrombi, vegetations, and normal variant structures) (Table 1 and Figure 1). Primitive cardiac tumors are rare, while metastases and pseudotumors are relatively common[1,2]. The updated classification of cardiac masses, published by World Health Organization in 2015[3] includes benign tumors, non-neoplastic masses, malignant lesions, and pericardial masses (Table 2). The prevalence of primary cardiac tumors is 1:2000 autopsies and that of secondary tumors (metastases) it is 1:100 autopsies. Secondary tumors are more common than primary lesions (secondary/primary ratio 20:1). Approxi

| Site of mass | Normal variant structures | Abnormal masses |

| Left ventricle | False tendon, trabeculations, papillary muscle | Thrombus, tumor |

| Left atrium | Coumadin ridge, fibromuscular membrane | Thrombus, tumor |

| Right ventricle | Moderator band, trabeculations, pacemaker leads | Thrombus, tumor |

| Right atrium | Crista terminalis, eustachian valve, Chiari network, lipomatous hypertrophy of atrial septum, pacemaker leads | Thrombus, tumor |

| Valves | Lambl’s excrescence (aortic valve), annular calcification | Thrombus, infective vegetations (native valve and prosthesis), tumor (native valve) |

| Pericardium | Pericardial fat | Pericardial malignant mesothelioma |

| Paracardiac | Hiatal hernia | Mediastinal/thoracic tumor compression |

| Group | Histologic type |

| Benign congenital/childhood | Rhabdomyoma, histiocytoid cardiomyopathy, congenital or childhood fibroma, cystic tumor of the atrioventricular node, hamartomas, germ cell tumors, schwannoma, granular cell tumor |

| Non-neoplastic tumors of adults | Papillary fibroelastoma, lipomatous hypertrophy of atrial septum |

| Neoplastic benign tumors | Myxoma, lipoma, hemangioma |

| Malignant tumors | Angiosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, pericardial malignant mesothelioma, lymphoma |

| Intermediate behavior | Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, low-grade angiosarcoma, infiltrating hemangiomas, cardiac paraganglioma, solitary fibrous tumor of the pericardium, adult cellular rhabdomyoma |

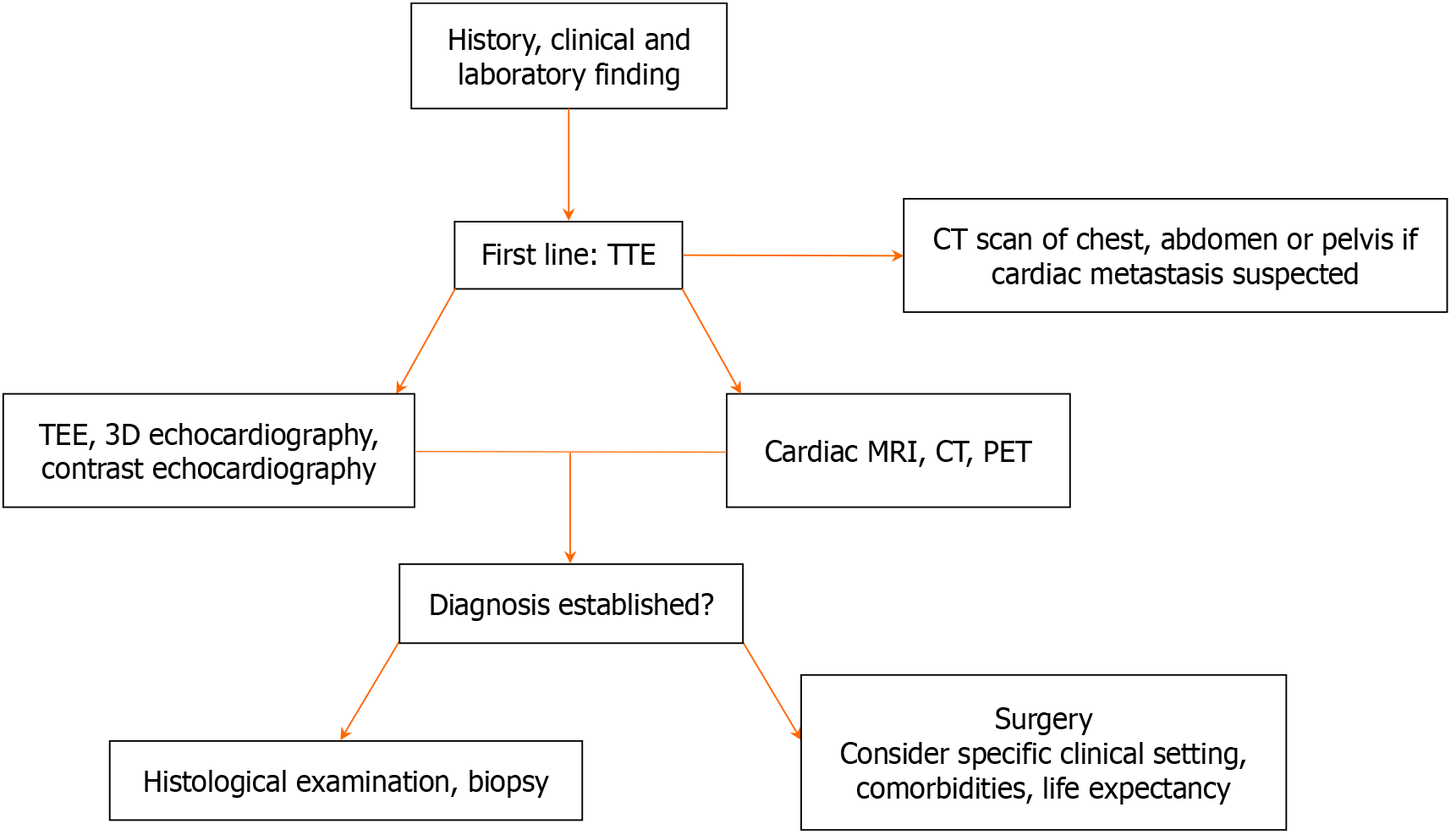

Cardiac masses frequently pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, moreover they may be asymptomatic or found incidentally during evaluation for an apparently unrelated problem[4,5]. The first-level noninvasive exa

In the article by Huffaker et al[8], published in the current issue of the World Journal of Clinical Cases, the authors describe a case of a 30-year-old woman with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) with a tricuspid valve mass, that was detected during a routine echocardiography in the cardio-oncology clinic, in absence of symptoms or clinical signs. The finding was not evident in previous echocardiographic examinations. The patient had a remarkable cancer history (breast and ovarian cancer, soft tissue, and bone sarcoma), so this new cardiac mass raised a reasonable suspicion for a primary cardiac tumor or metastasis. After a multi-disciplinary approach (cardio-oncology specialist, multimodality cardiac imaging, cardiothoracic surgeons, and interventional cardiologists) a decision was made to surgically remove the mass. Quite surprisingly, the mass was histologically identified as a thrombus with no evidence of malignancy.

LFS, firstly described in 1969, is an inherited autosomal dominant disorder, associated with abnormalities in the tumor suppressor protein P53 gene (TP53) located on chromosome 17p13. LFS predisposes to different types of malignant tumors in several organs and at a relatively young age; it is also known as the sarcoma, breast, leukemia, and adrenal gland cancer syndrome[8].

Tricuspid valve masses are usually related to cardiac thrombi or infective vegetations in endocarditis, especially in patients with central venous lines, vascular catheters, or pacemaker/defibrillator leads. Primary tumors are less frequently encountered, and papillary fibroelastoma is the most frequent (and benign) tricuspid tumor. The mean age of occurrence is 70-80 years with no sex difference.

The patient described by Huffaker et al[8] had a high pretest probability of primary cardiac malignancy or metastasis but the final diagnosis was valve thrombus, in line with the well-known association between cancers and thrombosis. It is important to note that the mass showed enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), suggesting the presence of vascularization, which is common in tumors but is an exceedingly rare finding on CMR in cases of thrombus.

Multimodality imaging in patients with cardiac masses is fundamental for differential diagnosis, treatment, and surgical planning. The characteristics of the mass defined by echocardiography, CMR, cardiac computed tomography, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography surely serve to guide clinicians. In particular, CMR is currently the gold standard for noninvasive tissue characterization. CMR evaluates the relationship between the tumor and adjacent structures, detects expansion and infiltration of the lesion, and predicts the malignant nature of a mass with a high precision. However, as demonstrated in this case report, the clinical complexity of cancer patients, in particular those with rare syndromes, requires a multidisciplinary approach and an open mind to go beyond flow charts and diagnostic algorithms. In other words it requires the ability to “think outside the box”.

| 1. | Basso C, Rizzo S, Valente M, Thiene G. Cardiac masses and tumours. Heart. 2016;102:1230-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tyebally S, Chen D, Bhattacharyya S, Mughrabi A, Hussain Z, Manisty C, Westwood M, Ghosh AK, Guha A. Cardiac Tumors: JACC CardioOncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol. 2020;2:293-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 4th ed. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2015. |

| 4. | Quah KHK, Foo JS, Koh CH. Approach to Cardiac Masses Using Multimodal Cardiac Imaging. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2023;48:101731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pazos-López P, Pozo E, Siqueira ME, García-Lunar I, Cham M, Jacobi A, Macaluso F, Fuster V, Narula J, Sanz J. Value of CMR for the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:896-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Castrichini M, Albani S, Pinamonti B, Sinagra G. Atrial thrombi or cardiac tumours? The image-challenge of intracardiac masses: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020;4:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bussani R, Castrichini M, Restivo L, Fabris E, Porcari A, Ferro F, Pivetta A, Korcova R, Cappelletto C, Manca P, Nuzzi V, Bessi R, Pagura L, Massa L, Sinagra G. Cardiac Tumors: Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huffaker T, Pak S, Asif A, Otchere P. Tricuspid mass-curious case of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:1936-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/