Published online Aug 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i24.5596

Revised: May 21, 2024

Accepted: June 12, 2024

Published online: August 26, 2024

Processing time: 136 Days and 1.5 Hours

Idiopathic omental infarction (IOI) is challenging to diagnose due to its low incidence and vague symptoms. Its differential diagnosis also poses difficulties because it can mimic many intra-abdominal organ pathologies. Although hypercoagulability and thrombosis are among the causes of omental infarction, venous thromboembolism scanning is rarely performed as an etiological investigation.

The medical records of the 5 cases, who had the diagnosis of IOI by computed tomography, were examined. The majority of the patients were male (n = 4, 80%) and the mean age was 31 years (range: 21-38). The patients had no previous abdominal surgery or a history of any chronic disease. The main complaint of all patients was persistent abdominal pain. Omental infarction was detected in all patients with contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Conservative treatment was initially preferred in all patients, but it failed in 1 patient (20%). After discharge, all patients were referred to the hematology department for thrombophilia screening. Only 1 patient applied for thrombophilia screening and was homozygous for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (A1298C mutation) and heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation.

IOI should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with progressive and/or persistent right side abdominal pain. Investigating risk factors such as hypercoagulability in patients with IOI is also important in preventing future conditions related to venous thromboembolism.

Core Tip: Idiopathic omental infarction is a rare cause of acute abdominal pain and should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with progressive right side abdominal pain. Omental infarction is idiopathic in cases whose etiology could not be established. Although hypercoagulability and thrombosis are among the causes of omental infarction, venous thromboembolism screening is rarely performed as an etiological investigation. Investigating risk factors such as hypercoagulability in patients with idiopathic omental infarction is crucial in preventing future conditions related to venous thromboembolism.

- Citation: Kar H, Khabbazazar D, Acar N, Karasu Ş, Bağ H, Cengiz F, Dilek ON. Are all primary omental infarcts truly idiopathic? Five case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(24): 5596-5603

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i24/5596.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i24.5596

Idiopathic omental infarction (IOI), which is a rare cause of acute abdominal pain, was first described by Bush in 1896. It is an acute vascular pathology that develops as a result of impaired perfusion of the greater omentum[1,2]. Due to its low incidence and vague symptoms, it is challenging to diagnose without the support of radiological evidence. In most cases, IOI is confused with acute appendicitis or acute cholecystitis since the pain is mainly localized in the right side of the abdomen[3,4]. Omental infarction (OI) was named as primary and/or idiopathic in cases whose etiology could not be established. Although hypercoagulability and thrombosis are among the causes of OI, venous thromboembolism (VTE) screening is rarely performed as an etiological investigation[2]. In this study, we aimed to present 5 cases of IOI in the light of the current literature and to evaluate the place for VTE screening in etiology.

The main complaint of all patients was persistent abdominal pain, and the mean duration of pain prior to hospital admission was 3.5 d.

None of the patients had a history of regular drug use. The majority of the patients were male (n = 4, 80%) and the mean age was 31.4 years (range: 21-38). The demographics and the clinical features of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

| Patient number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Age in yr | 21 | 28 | 34 | 36 | 38 |

| Sex | M | F | M | M | M |

| Smoking status | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Duration of symptoms in d | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 5 |

| Pain localization | Epigastrium | URQ | Epigastrium/LRQ | URQ | URQ |

| Peritoneal irritation sign | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| CT localization | URQ, inframesocolic omentum | URQ, anterior to the ascending colon | ULQ, inframesocolic omentum | URQ, lateral to the hepatic flexura | URQ, inframesocolic omentum |

| Lesion diameter in mm | 40 × 85 | 35 × 45 | 23 × 32 | 40 × 73 | 52 × 58 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 23 | 24 |

| WBC as 109/L | 10.94 | 16.87 | 15.29 | 8.64 | 6.77 |

| CRP 0-5 mg/L | 2.13 | 0.02 | 2.99 | 5.88 | 8.70 |

| PT 9.4-12.5/s | 13.1 | 10.1 | 14.2 | 12.5 | 11.3 |

| CK 30-200 U/L | 261 | 93 | 142 | 297 | 287 |

| Management | Medical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | Medical |

| LOS in d | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

The patients had no previous abdominal surgery or a history of any chronic disease.

No family history of liver disease, bleeding disorder, or other coagulopathy was detected in any patient.

One of the patients had an acute abdomen examination. Other patients had abdominal tenderness.

Laboratory tests were unremarkable.

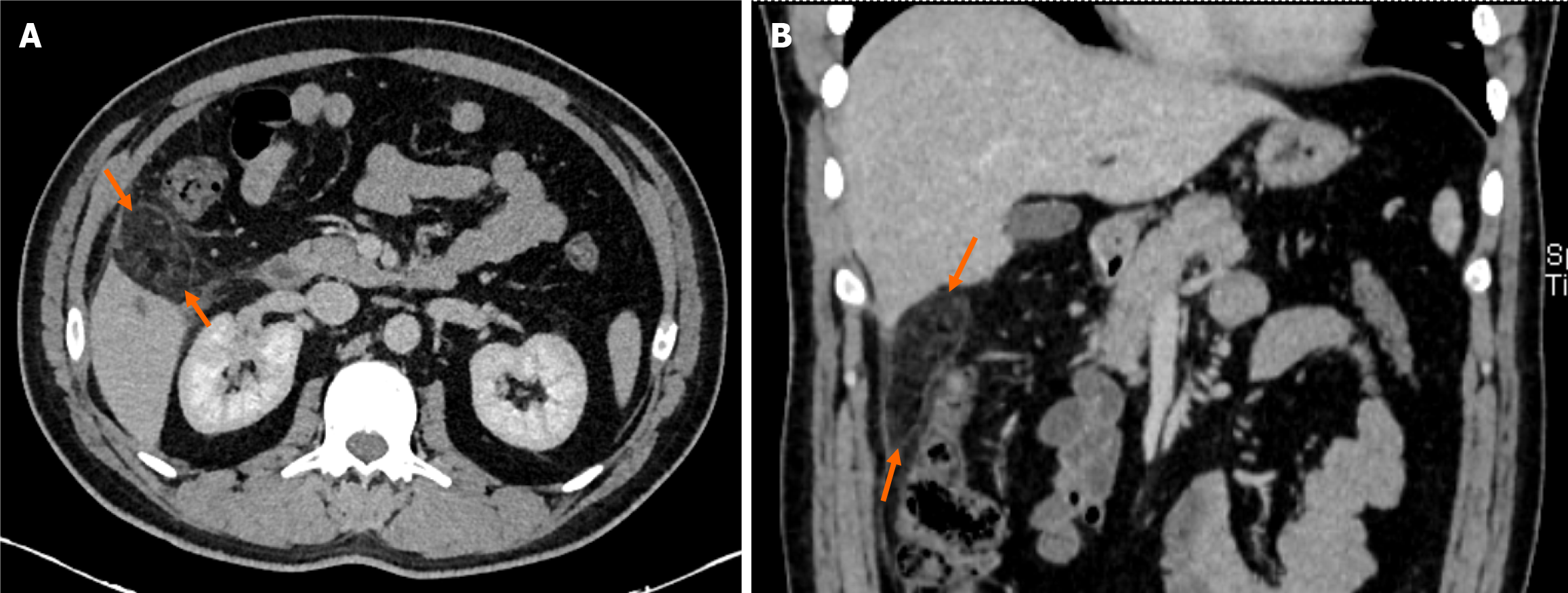

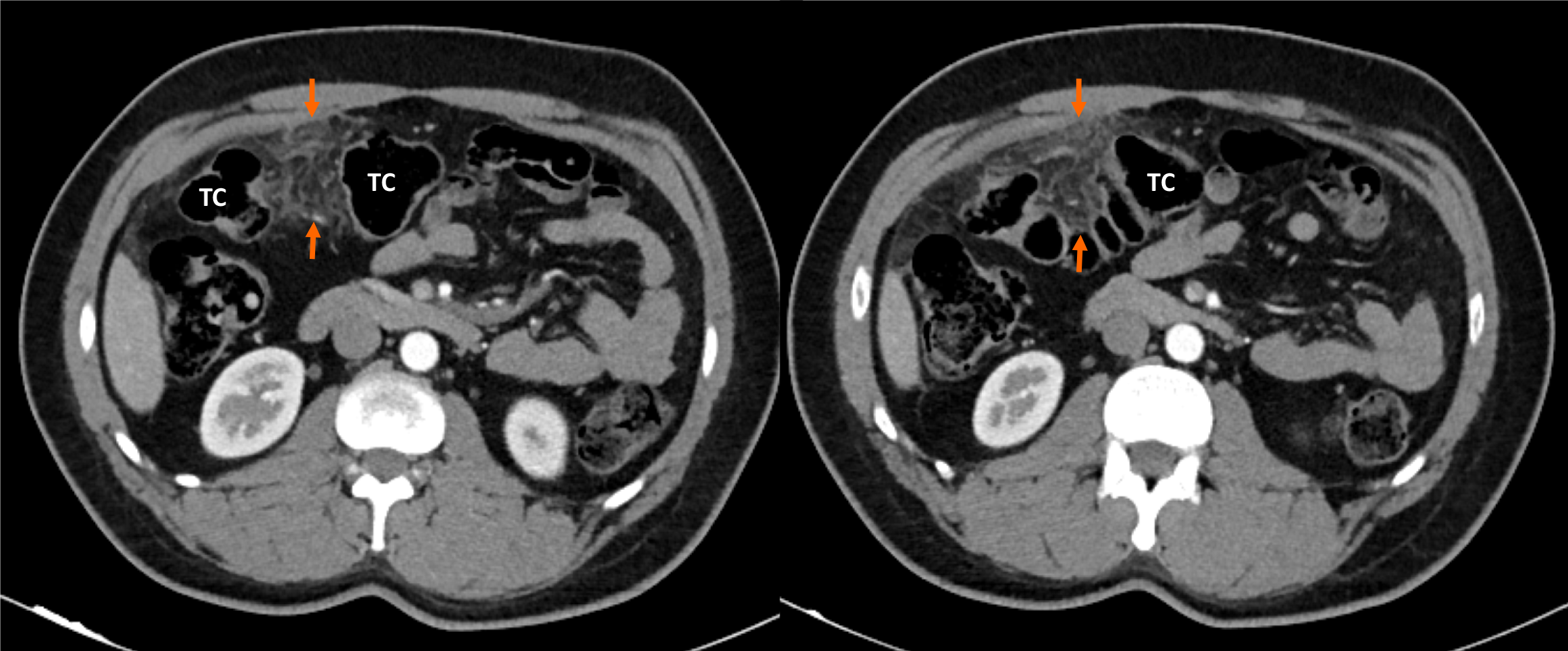

Computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in all cases (Figures 1 and 2). Omental fat thickening and stranding were detected as common findings without any accompanying abnormality on CT scans.

Physical examination, laboratory tests, and abdominal ultrasound as the primary diagnostic approaches were insufficient for the definitive diagnosis. OI was diagnosed in all patients with contrast-enhanced CT by an experienced gastroin

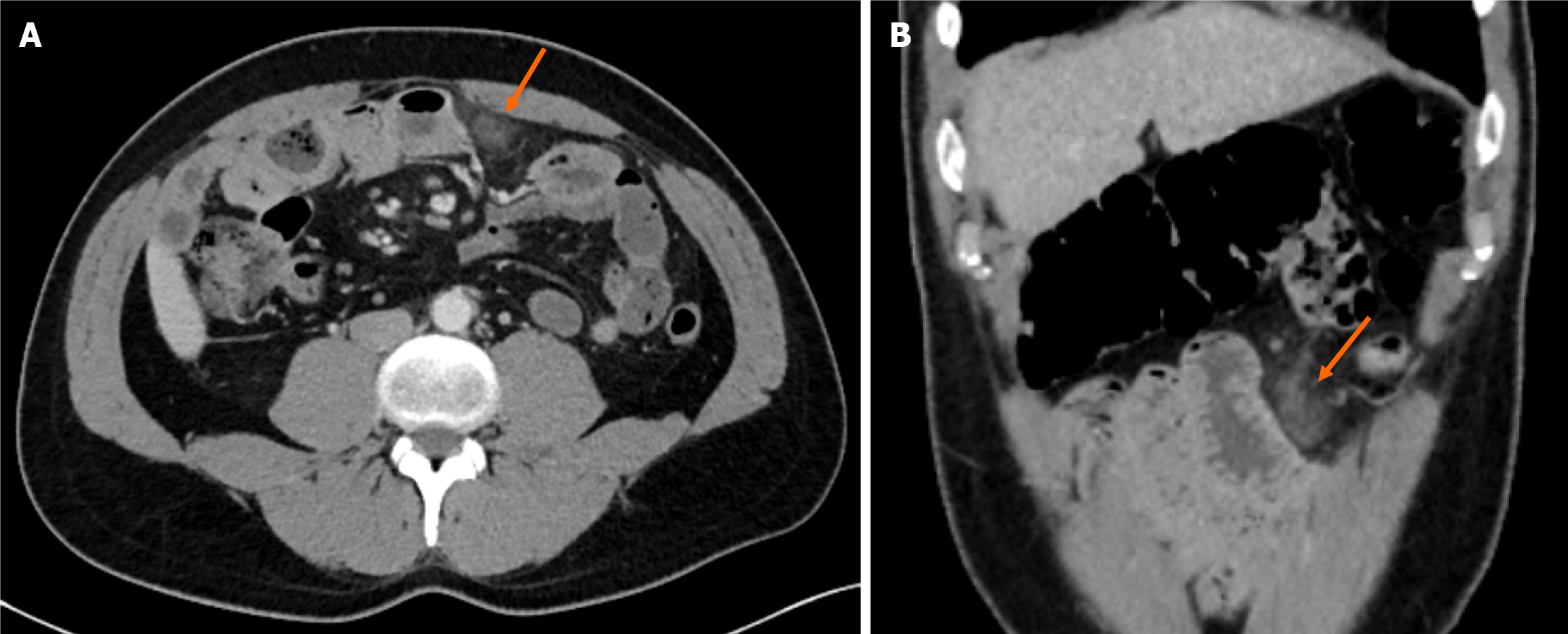

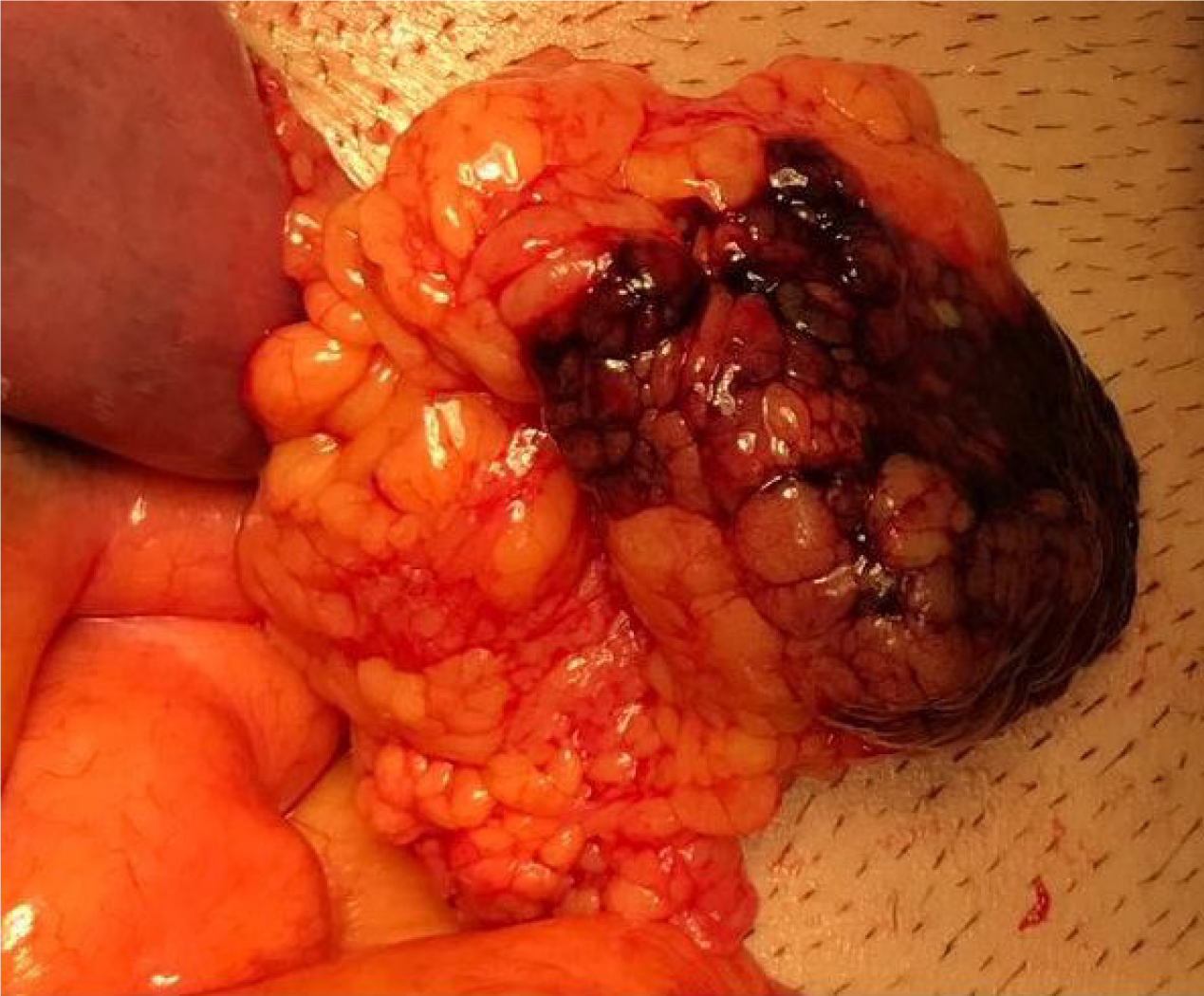

Medical treatment (oral intake restriction, analgesics, proton pump inhibitors, antiemetics, and antibiotics) was administered to all patients. The mean duration of hospitalization was 3.8 d. Only 1 patient, who developed diffuse peritonitis, required surgical intervention on the 2nd day of the conservative follow-up. During the operation, an OI zone with a diameter of 3 cm adjacent to the mid-transverse colon was found in accordance with CT (Figures 3 and 4). No other abdominal pathology was observed during the exploration. Partial omental resection and appendectomy were performed. Pathological examination of the specimen revealed omental edema, congestion, and venous dilatation/thrombosis.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged without any complications. On the 8th day after discharge, the same patient presented with abdominal distension, constipation, nausea, and vomiting and was hospitalized with the diagnosis of adhesive ileus. Since the clinical process was unresponsive to the conservative management, the patient was re-operated. The other 4 patients who received medical treatment were discharged without any problems. After discharge, all patients were referred to the hematology department for thrombophilia screening. Thrombophilia screening was performed on 1 patient who applied to the hematology outpatient clinic. The patient was homozygous for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (A1298C mutation) and heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation. Anticoagulant therapy was started.

Although IOI is rare, advances and increasing accessibility in radiologic techniques have increased the incidence of this condition. It has an incidence equivalent to less than 4 cases per 1000 appendicitis cases[5,6]. Eighty-five percent of OI cases were reported as adult patients, and the cases were between 30-50 years of age. It is twice as common in males than in females[7,8]. In our case series, the mean age was 31.4 years, and the rate of male patients was 80% in accordance with the literature.

Omental infarcts are divided into two main groups according to the pathogenesis as primary and secondary. Secondary infarcts develop due to the causes of venous thrombosis (e.g., hypercoagulability, vasculitis, polycythemia, and vascular anomalies) and omental torsions caused by cysts, tumors, hernias and adhesions. The pathogenesis of IOI has not been clearly determined, but anatomical malformations such as bifurcated or accessory omentum, sudden movements, vigorous exercise, heavy food intake, hyperperistalsis, and obesity have been introduced as predisposing factors[4,9]. There are studies showing that obesity is an important risk factor, especially in the pediatric patient group[10,11]. None of the patients from our case series were obese.

OI has been reported to occur more frequently on the right side. Many authors have suggested that the omentum has an abnormal and fragile vasculature in the right quadrant and is consequently more susceptible to infarction[12,13]. As another reason, the omentum is longer and more mobile in the right side[7]. In our series, the OI was located in the right upper quadrant in 4 cases (80%).

One of our five patients, who was initially considered as IOI, was then diagnosed as secondary OI since the patient was homozygous for the MTHFR A1298C mutation and heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation after thrombophilia screening. MTHFR is a homocysteine metabolic regulatory enzyme. Mutations in the MTHFR gene reduce enzyme activity and thus increase plasma homocysteine. Hyperhomocysteinemia can destroy the vascular endothelium and alter blood coagulation status as well as platelet function and eventually participate in the pathogenesis of VTE[14].

Factor V Leiden mutation is the most common genetic risk factor for VTE. It is characterized by a weak anticoagulant response to activated protein C. Population studies have shown that approximately 10% of factor V Leiden heterozygotes develop VTE during their lifetime. This rate can be up to 25%-40% in thrombophilic families. It has also been reported that the risk of VTE is further increased in factor V Leiden heterozygotes accompanied by obesity and minor trauma[15,16].

This actually overlaps with the predisposing factors predicted for IOI. When the case reports and series of OI from the early 2000s to the present were reviewed, it was observed that thrombophilia screening was performed in 6 cases (Table 2). While 4 cases were found to be non-determined[3,17-19], the other case was diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome and presented as secondary OI[20]. In the last case, protein C and protein S deficiency was detected in the thrombophilia screening performed on the development of thrombosis in the superior mesenteric vein in the early period after OI[21].

| Ref. | Age in yr/sex | Hypercoagulable states | Treatment |

| Lindley and Peyser[3] | 42/male | Unremarkable | Surgical (laparoscopic) |

| Subasinghe et al[17] | 37/male | Unremarkable | Surgical |

| Kaya et al[18] | 25/male | Unremarkable | Medical |

| Porras et al[19] | 11/male | Unremarkable | Medical |

| Alshehri et al[20] | 46/male | Antiphospholipid syndrome | Medical |

| Patle et al[21] | 41/female | Protein C and protein S deficiencies | Surgical (laparoscopic) |

| Present case | 38/male | Homozygous for methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (A1298C) mutation and heterozygous for factor V Leiden mutation | Medical |

In addition, D-dimer and fibrin degradation products were also investigated and were higher in some publications[10]. Although the fact that which patients should be screened for thrombophilia is still a controversy in the literature, it has been stated that screening can be beneficial in thrombosis of unusual areas such as spleen, mesentery, and liver[22]. Considering the progressive edema and hemorrhagic necrosis secondary to the venous stasis and thrombosis in the pathophysiology of the disease, questioning the history of VTE carefully in these patients and their families, and consulting hematology in terms of thrombophilia screening may be beneficial[7].

Although OI usually occurs on the right side of the omentum, it can develop wherever the omental tissue is present[20]. Therefore, the chief complaint in 90% of the cases is right upper and/or lower quadrant abdominal pain[5,23]. Acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, renal colic, acute diverticulitis, and epiploic appendicitis are primarily considered in differential diagnosis[2,24]. IOI has no early specific symptoms and is usually characterized by progressive, persistent abdominal pain. Physical examination may reveal the signs of peritoneal irritation from mild, localized irritation to generalized peritonitis. The mass can be palpated depending on the patient’s body structure and the size of the omental tissue involved[4]. Consistent with the literature, abdominal pain was predominantly located in the right side of the abdomen in our cases.

In the past, the diagnosis of OI was often made incidentally during the laparotomies performed for acute abdomen, but today abdominal CT imaging has become the gold standard for diagnosis[1,4]. OI demonstrates different imaging findings on CT. It generally appears as a mild haziness or a large (> 5 cm) fatty, encapsulated mass, with stranding adjacent to the colonic segments, especially in the ascending colon. The adjacent colon is usually spared, but reactive colonic wall thickening can be seen[25]. On ultrasound, a hyperechoic, incompressible oval mass can be detected in the area of maximum tenderness[26].

Currently, there is no standard treatment modality for OI. Basically, there are two options: Conservative (medical) treatment and early laparoscopic surgical intervention[2]. Conservative treatment is recommended for the first 24-48 h if a confirmed diagnosis of OI can be made by typical clinical signs and imaging studies[6]. Intravenous fluid therapy, analgesics, antiemetics, and antibiotics are the first-line treatments combined with stopping or reducing oral intake. However, if the diagnosis is doubtful or conservative treatment fails, surgical exploration should be performed without delay[2,27].

The consensus of the supporters of conservative treatment is that OI is a self-limiting pathology, and this hypothesis is encouraged by long-term CT follow-ups. The risks of anesthesia and surgery that may arise as a result of surgical intervention are also eliminated[20]. On the other hand, those who recommend early surgical intervention advocate that both symptom control and patient discharge can be achieved earlier with surgery. They also suggest that removing the distorted omental tissue will theoretically reduce the likelihood of abscess and secondary adhesions[7].

In patients scheduled for surgical intervention, a laparoscopic approach is initially recommended for the lower morbidity[5,27]. In their systematic review, Medina-Gallardo et al[8] stated that conservative treatment was effective in most patients, but surgery had the advantage in terms of length of hospital stay. Young age and leukocytosis ≥ 12000/μL were found to be predictive factors for conservative treatment failure. The only patient in whom the conservative treatment failed in our series, had leukocytosis of 15000/μL and was 34-years-old, and this was consistent with the literature data. It should also be considered that the patients who underwent surgical intervention may be candidates for reoperations, as in our case. Therefore, patient selection for the surgical approach should be performed meticulously.

Although IOI is difficult to recognize with primary diagnostic methods, it can be easily diagnosed by CT and can be treated conservatively. Thus unnecessary surgery and anesthesia risks can be avoided. OI can occur anywhere omental tissue is present. Therefore, diseases such as acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, renal colic, acute diverticulitis, and epiploic appendicitis should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis. Investigating risk factors such as hypercoagulability in patients with IOI is also important in preventing future conditions related to VTE.

| 1. | Udechukwu NS, D'Souza RS, Abdulkareem A, Shogbesan O. Computed tomography diagnosis of omental infarction presenting as an acute abdomen. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13:583-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tannoury J, Yaghi C, Gharios J, Abboud B. Omental ischemia. Presse Med. 2016;45:824-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lindley SI, Peyser PM. Idiopathic omental infarction: One for conservative or surgical management? J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjx095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peirce C, Martin ST, Hyland JM. The use of minimally invasive surgery in the management of idiopathic omental torsion: The diagnostic and therapeutic role of laparoscopy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:125-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abdulaziz A, El Zalabany T, Al Sayed AR, Al Ansari A. Idiopathic omental infarction, diagnosed and managed laparoscopically: a case report. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:193546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Barai KP, Knight BC. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic omental infarction: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:138-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park TU, Oh JH, Chang IT, Lee SJ, Kim SE, Kim CW, Choe JW, Lee KJ. Omental infarction: case series and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Medina-Gallardo NA, Curbelo-Peña Y, Stickar T, Gardenyes J, Fernández-Planas S, Roura-Poch P, Vallverdú-Cartie H. Omental infarction: surgical or conservative treatment? a case reports and case series systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;56:186-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta R, Farhat W, Ammar H, Azzaza M, Lagha S, Cheikh YB, Mabrouk MB, Ali AB. Idiopathic segmental infarction of the omentum mimicking acute appendicitis: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;60:66-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsunoda T, Sogo T, Komatsu H, Inui A, Fujisawa T. A case report of idiopathic omental infarction in an obese child. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:513634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McCusker R, Gent R, Goh DW. Diagnosis and management of omental infarction in children: Our 10 year experience with ultrasound. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:1360-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hwang JK, Cho YJ, Kang BS, Min KW, Cho YS, Kim YJ, Lee KS. Omental infarction diagnosed by computed tomography, missed with ultrasonography: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:972-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Battaglia L, Belli F, Vannelli A, Bonfanti G, Gallino G, Poiasina E, Rampa M, Vitellaro M, Leo E. Simultaneous idiopathic segmental infarction of the great omentum and acute appendicitis: a rare association. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paradkar MU, Padate B, Shah SAV, Vora H, Ashavaid TF. Association of Genetic Variants with Hyperhomocysteinemia in Indian Patients with Thrombosis. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2020;35:465-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Genet Med. 2011;13:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Van Cott EM, Khor B, Zehnder JL. Factor V Leiden. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:46-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Subasinghe D, Jayasinghe R, Ranaweera G, Kodithuwakku U. Spontaneous omental infarction: A rare case of acute abdomen. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10:2050313X221135982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaya A, Kaya SY, Baydar H, Bavunoğlu I. Omental infarction in mild Covid-19 infection. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:326-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Porras L E, Barasoain M A, Ríos M V, Botija A GM, Solé D C. [Omental infarction, unusual cause of abdominal pain]. Andes Pediatr. 2022;93:434-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alshehri M, Khalifa H, Alqahtani A, Aburahmah M. Secondary Omental Infarction in a Patient with a Hypercoagulable State. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Patle NM, Tantia O, Das PC, Mukherjee J, Prasad P. Omental gangrene and porto-mesenteric thrombosis in a patient of protein C and protein s deficiency. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:409-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parakh RS, Sabath DE. Venous Thromboembolism: Role of the Clinical Laboratory in Diagnosis and Management. J Appl Lab Med. 2019;3:870-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Amo Alonso R, de la Peña Cadenato J, Loza Vargas A, Santos Santamarta F, Sánchez-Ocaña Hernández R, Arenal Vera JJ. Infarction of the greater omentum. Case report. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:706-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aiyappan SK, Ranga U, Veeraiyan S. Omental infarct mimicking acute pancreatitis. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:1393-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kamaya A, Federle MP, Desser TS. Imaging manifestations of abdominal fat necrosis and its mimics. Radiographics. 2011;31:2021-2034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tonerini M, Calcagni F, Lorenzi S, Scalise P, Grigolini A, Bemi P. Omental infarction and its mimics: imaging features of acute abdominal conditions presenting with fat stranding greater than the degree of bowel wall thickening. Emerg Radiol. 2015;22:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Itenberg E, Mariadason J, Khersonsky J, Wallack M. Modern management of omental torsion and omental infarction: a surgeon's perspective. J Surg Educ. 2010;67:44-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/