Published online Jul 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4440

Revised: May 8, 2024

Accepted: May 28, 2024

Published online: July 16, 2024

Processing time: 83 Days and 14.7 Hours

Gelastic seizure (GS) is a rare type of epilepsy that most commonly appears in patients with hypothalamic hamartoma. It is rarely associated with other types of brain damage. This particular type of epilepsy is relatively rare and has few links to other brain lesions. Temporal lobe malacia is mostly caused by cerebral infarc

A 73-year-old female, diagnosed case of GS, presented with repetitive stereotyped laughter a month prior to presentation, happening multiple times daily and with each time lasting for 5-15s. Electroencephalogram displayed a focal seizure seen in the right temporal region. Magnetic resonance imaging head with contrast showed a right temporal lobe malacia. The patient was started on levetiracetam daily. The patient indicated that they had fully recovered and were not experiencing any recurrent or stereotyped laughter during their daily routines. These results remained consistent even after a one-year follow-up period.

GS can be caused by temporal lobe malacia, which is an uncommon but poten

Core Tip: Gelastic seizure (GS) is an uncommon seizure type. Temporal lobe malacia is an uncommon but potentially serious cause of GS. We report a case of GS in a woman with temporal lobe malacia which was reported for the first time in the literature.

- Citation: Liao YS, Gao LL, Lin M, Wu CH. Temporal lobe malacia as a rare cause of gelastic seizure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(20): 4440-4445

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i20/4440.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4440

Gelastic seizure (GS) is a rare type of seizure that accounts for 0.8%[1] of all epilepsies and is characterized by repeated stereotyped laughter, first described by Trousseau in 1868.GS is usually arised from hypothalamic hamartomas (HH), most commonly seen in children[2,3]. Even though, GS can occur due to different causes seen more frequently in adults[4,5]. Focal brain lesions associated with GS typically occur in the frontal or temporal region. These regions are key areas of the brain responsible for different functions, and there is a close correlation between GS and damage to these areas. We report a case of GS due to a large malacia in the temporal lobe. No report focusing on GS associated with temporal lobe malacia has been reported.

Family members complained that the patient had repetitive stereotyped laughter for one month, happening multiple times daily and with each time lasting for 5-15 s.

A female patient, aged 73, was taken in for treatment in the Neurology Department of our hospital due to repetitive stereotyped laughter. A month ago, she began to experience laughter attacks, which occurred almost every day and lasted for 5-15 s. No loss of consciousness or incontinence occurred during the attack. Occasionally, she experiences an inexplicable feeling just before laughing, but denies having any subjective sensation of joy.

The patient had a 20-year history of hypertension and was regularly treated with felodipine sustained-release tablet 2.5 mg per day, with good blood pressure control. She has had a history of cerebral infarction for more than 4 years, and regularly takes oral treatment of aspirin enteric-coated tablet 100 mg per day.

She resulted from a non-consanguineous marriage and arrived at full term without encountering any perinatal complications. Secondary school diploma. Denied smoking and drinking history. There was no history of diabetes, cancer, or dementia and no family history of epilepsy.

At admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 142/71 mmHg, and she had a pulse rate of 79 beats per minute, accompanied by a respiration rate of 19 breaths per minute. The physical examination of the cardiopulmonary abdomen and other major internal medicine showed no abnormality. Neurological examination: clear mind, slightly slow response, but relevant to the question, Mini-mental State Examination score 26 points, cranial nerve examination no abnormalities, left limb muscle strength level Ⅱ, right limb muscle strength level Ⅴ, left Babinski sign positive.

Serum laboratory findings were normal.

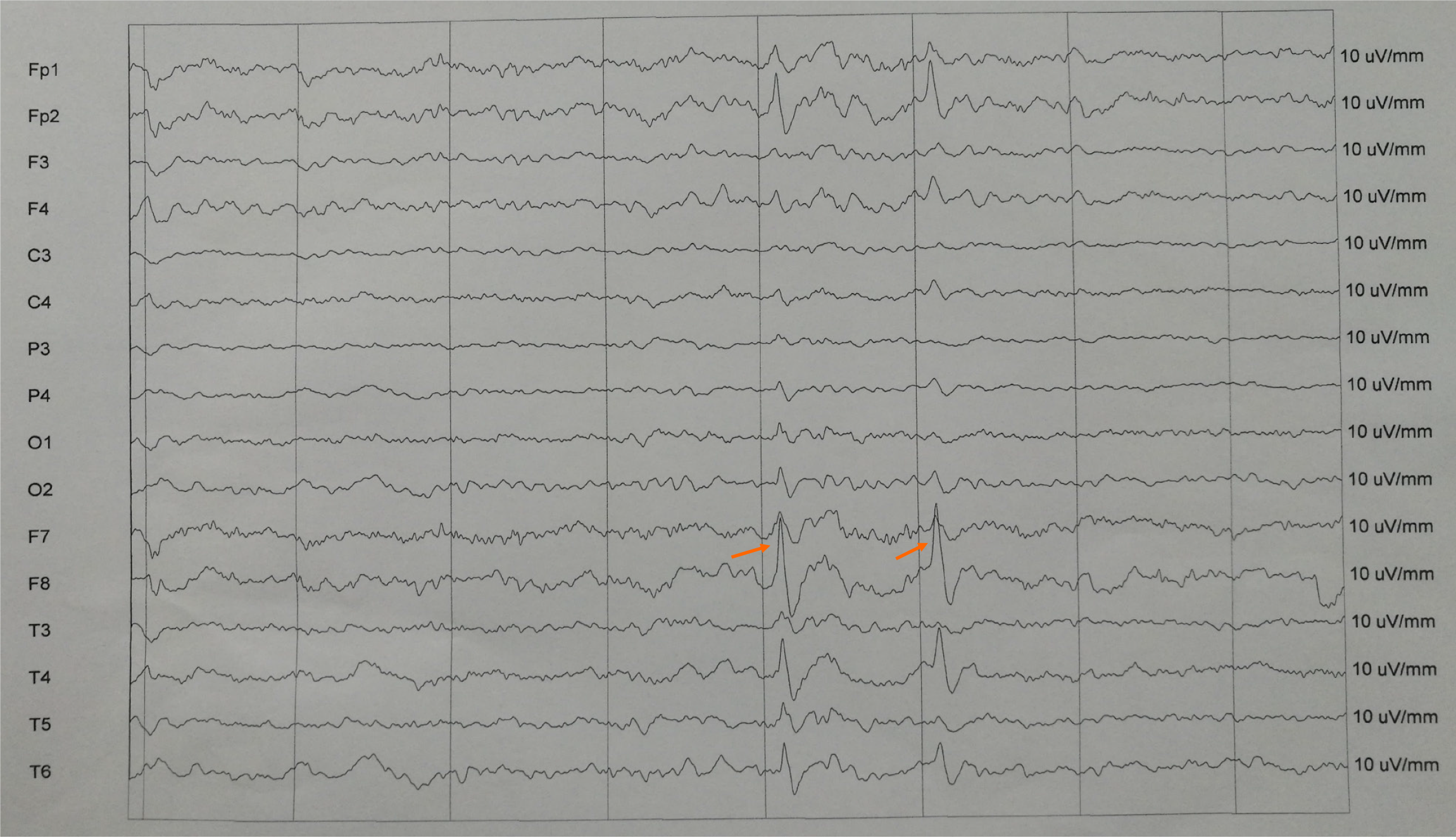

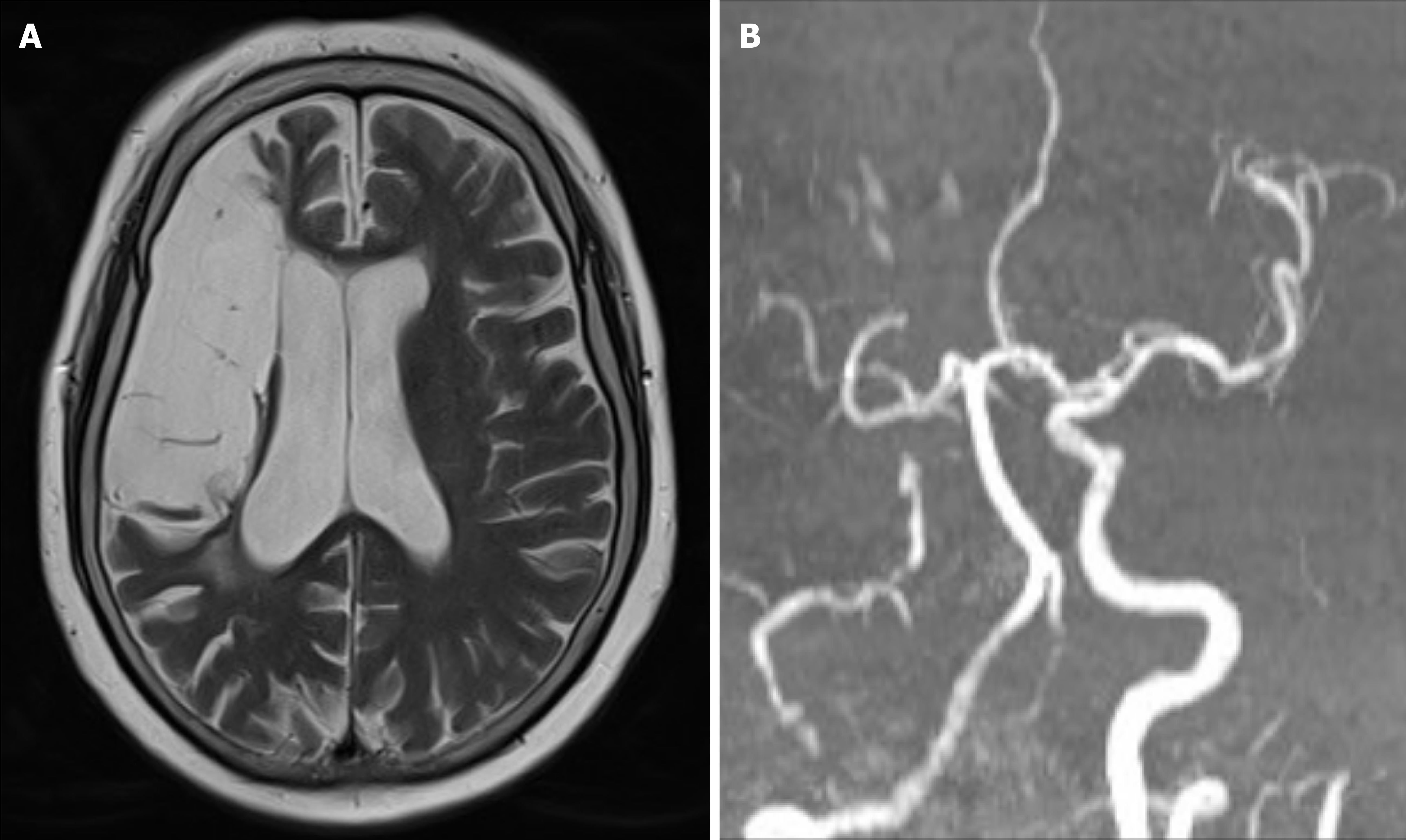

She was monitored on electroencephalogram (EEG) (Trex HD, Natus, America), and seizures were recorded. Ictal onset for one seizure appeared to be from the right anterior temporal (F8) as seen in Figure 1. There are some spike and wave discharges at the right anterior temporal region. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Magnetom Skyra, Siemens, Germany) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) were scheduled immediately due to the focal findings from the EEG. MRI of the brain showed a right temporal lobe malacia as seen in Figure 2A. And MRA view showing the right internal carotid artery occlusion (Figure 2B).

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the results of the EEG and the brain MRI, the patient was diagnosed with Gelastic seizures.

The patient was started on levetiracetam tablets regularly (500 mg bid; UCB Pharma S.A.). Half a month after admission, the family reported an improvement in the patient’s symptoms of repetitive stereotyped laughter. So, raise the levetiracetam tablets 1000mg bid and maintain it for a long time.

Two months later, the family reported no repetitive stereotyped laughter, and 24 hours ambulatory electroencephalogram (Easy, Cadwell, America) showed generalized slow waves without the occurrence of seizure activity in the right temporal region as seen in Figure 3. These results were maintained at the 1-year follow-up.

GS is an uncommon seizure type. In 1971, Gascon and Lombroso defined the characteristics of GS as: “stereotypic, repetitive, out of social context laughter attacks, which may be related to ictal or interictal discharges on the EEG, or may be associated with other types of seizures”[6]. It is most frequently observed in childhood with HH. Adult presentations have been reported without being associated with HH[7]. Their association with other types of cerebral lesions is rare, and no report focusing on GS associated with temporal lobe malacia has been reported.

The pathophysiological mechanisms of GS are still undefined, and little is known about which pathways promote laughter. Previous studies have suggested that the temporal lobe is involved in the network-generating laughter[8,9]. Sarigecili et al[10] reported a case of GS caused by nongalenic pial arteriovenous fistula in the right temporal lobe and joyful laughter occurred as a result. Joswig et al[11] reported a case of GS originating from the left temporal cortex and middle temporal lobe, which stimulated the anterior superior temporal gyrus to cause a typical burst of laughter. Dericioglu et al[12] reported a case of GS due to right temporal cortical dysplasia and laughter attacks as a result. These studies demonstrate the importance of the temporal lobe in GS.

The malacia located in the right temporal lobe is believed to be the trigger for the seizure in this instance. Temporal lobe malacia is mostly caused by cerebral infarction or cerebral hemorrhage, which can lead to seizures. In our case, the patient had a history of cerebral infarction for more than 4 years, and the MRA view showed the right internal carotid artery occlusion. 3%-30% of patients after stroke may develop post-stroke epilepsy. Several studies have reported that the changes after stroke, including critically decreased regional blood flow, a low regional cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen, and increased blood-brain barrier permeability made the brain prone to seizures[13,14]. Zhao et al[14] found that large infarction and frontal and temporal cortex lesions are significant risk factors for post-stroke seizures. This is consistent with our report. In our case, the patient had a large malacia in the right frontal and temporal lobes due to occlusion of the right internal carotid artery. Therefore, we postulate that the clinical manifestations observed in the patient are attributable to decreased blood perfusion in these specific regions.

GS is often ignored by the public and even medical personnel, which leads to patients not being treated in time and suffering greater damage. Therefore, it is particularly important to strengthen the understanding of GS, early diagnosis, and intervention.

GS can be caused by temporal lobe malacia, which is an uncommon but potentially grave condition. The outcome of this present case exhibited the importance of the temporal lobe in the genesis of GS.

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their cooperation in relation to this report.

| 1. | Kovac S, Diehl B, Wehner T, Fois C, Toms N, Walker MC, Duncan JS. Gelastic seizures: incidence, clinical and EEG features in adult patients undergoing video-EEG telemetry. Epilepsia. 2015;56:e1-e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Téllez-Zenteno JF, Serrano-Almeida C, Moien-Afshari F. Gelastic seizures associated with hypothalamic hamartomas. An update in the clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:1021-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Uribe-San-Martin R, Ciampi E, Lawson-Peralta B, Acevedo-Gallinato K, Torrealba-Marchant G, Campos-Puebla M, Godoy-Fernández J. Gelastic epilepsy: Beyond hypothalamic hamartomas. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2015;4:70-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Savasta S, Budetta M, Spartà MV, Carpentieri ML, Trasimeni G, Zavras N, Villa MP, Parisi P. Gelastic epilepsy without hypothalamic hamartoma: three additional cases. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:87-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Striano S, Striano P. Clinical features and evolution of the gelastic seizures-hypothalamic hamartoma syndrome. Epilepsia. 2017;58 Suppl 2:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gascon GG, Lombroso CT. Epileptic (gelastic) laughter. Epilepsia. 1971;12:63-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iapadre G, Zagaroli L, Cimini N, Belcastro V, Concolino D, Coppola G, Del Giudice E, Farello G, Iezzi ML, Margari L, Matricardi S, Orsini A, Parisi P, Piccioli M, Di Donato G, Savasta S, Siliquini S, Spalice A, Striano S, Striano P, Verrotti A. Gelastic seizures not associated with hypothalamic hamartoma: A long-term follow-up study. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;103:106578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arroyo S, Lesser RP, Gordon B, Uematsu S, Hart J, Schwerdt P, Andreasson K, Fisher RS. Mirth, laughter and gelastic seizures. Brain. 1993;116 ( Pt 4):757-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mirandola L, Cantalupo G, d'Orsi G, Meletti S, Vaudano AE, Di Vito L, Vignoli A, Tassi L, Pelliccia V. Ictal semiology of gelastic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2023;140:109025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sarigecili E, Caglar E, Yildiz A, Okuyaz C. A rare concurrence: gelastic seizures in a patient with right temporal nongalenic pial arteriovenous fistula. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019;35:1055-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Joswig H, Rejas-Pinelo P, Suller A, McLachlan RS, Steven DA. Surgical treatment of extra-hypothalamic epilepsies presenting with gelastic seizures. Epileptic Disord. 2019;21:307-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dericioglu N, Cataltepe O, Tezel GG, Saygi S. Gelastic seizures due to right temporal cortical dysplasia. Epileptic Disord. 2005;7:137-141. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Xie C, Zhao W, Zhang X, Liu J, Xia Z. The Progress of Poststroke Seizures. Neurochem Res. 2024;49:887-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhao Y, Li X, Zhang K, Tong T, Cui R. The Progress of Epilepsy after Stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/