Published online Jul 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4384

Revised: May 14, 2024

Accepted: May 23, 2024

Published online: July 16, 2024

Processing time: 98 Days and 18.1 Hours

Enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) is an abnormal connection between the gastro

We present the case of a 46-year-old male who underwent gastrointestinal stromal tumour resection. Six days after the surgery, the patient presented with fever, fatigue, severe upper abdominal pain, and septic shock. Subsequently, lower ECFs were diagnosed through laboratory and imaging examinations. In addition to symptomatic treatment for homeostasis, total parenteral nutrition support was administered in the first 72 h due to dysfunction of the intestine. After that, we gradually provided EN support through the intestinal obstruction catheter in consideration of the specific anatomic position of the fistula instead of using the nasal jejunal tube. Ultimately, the patient could receive optimal EN support via the catheter, and no complications were found during the treatment.

Nutritional support is a crucial element in ECF management, and intestinal obstruction catheters could be used for early EN administration.

Core Tip: Early enteral nutrition support is crucial in the management of enterocutaneous fistulas. The method of enteral nutrition (EN) support could vary for enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) patients with different anatomical fistula locations. This study reported a novel, safe and efficient method of establishing early EN administration for ECF patients with intestinal obstruction catheters in which treatment strategies were tailored for rapid rehabilitation.

- Citation: Wang XT, Wang L, Liu AL, Huang JL, Li L, Lu ZX, Mai W. New application of intestinal obstruction catheter in enterocutaneous fistula: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(20): 4384-4390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i20/4384.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4384

Enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) presents any abnormal communication between the gastrointestinal tract and the skin or other organs which can occur after abdominal surgery[1,2]. Sepsis, electrolyte disorders, and malnutrition are all critical aspects to consider in ECF treatment. Particularly for high-risk malnourished patients, artificial nutritional support is an important approach for improving nutritional status and preventing further deterioration[3,4]. Generally, nutritional support consists of parenteral nutrition (PN) and enteral nutrition (EN). Over the past few decades, long-term total parenteral nutrition (TPN) has been the first choice for ECF management[5]. Studies have shown that TPN can reduce drainage from fistulas and accelerate the healing of wounds[6]. However, recent research has suggested that EN support should be given as soon as possible after patients are in remission[7]. To date, numerous attempts have been made to ensure safe and effective nutritional administration. In this article, we present a case in which a fistula was treated with early EN support through an intestinal obstruction catheter and discuss the advantages of the catheter.

A 46-year-old male presented to the gastroenterology ward with a complaint of fever, fatigue, severe upper abdominal pain, and unintentional weight loss.

The symptoms started six days before the presentation. The patient denied that he had experienced similar symptoms before.

Furthermore, the patient underwent resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumours six days prior.

The patient denied any family of other malignant tumours.

Physical examination revealed that the patient had abdominal distension, localized tenderness and rebound tenderness; wound dehiscence with purulent discharge; and hypoactive bowel sounds, with a body mass index calculated to be 18.14 kg/m2. His vital signs and laboratory test results at admission were as follows: temperature, 39.4%; pulse, 118 beats per minute; and blood pressure, 84/56 mmHg.

Laboratory investigations revealed white blood cell 20.4 × 109/L, C-reactive protein 243.41 mg/L, interleukin-6 54.12 ng/L, procalcitonin level 2.104 ng/L, haemoglobin 75 g/L, total protein 43.1 g/L, and serum albumin 20.4 g/L.

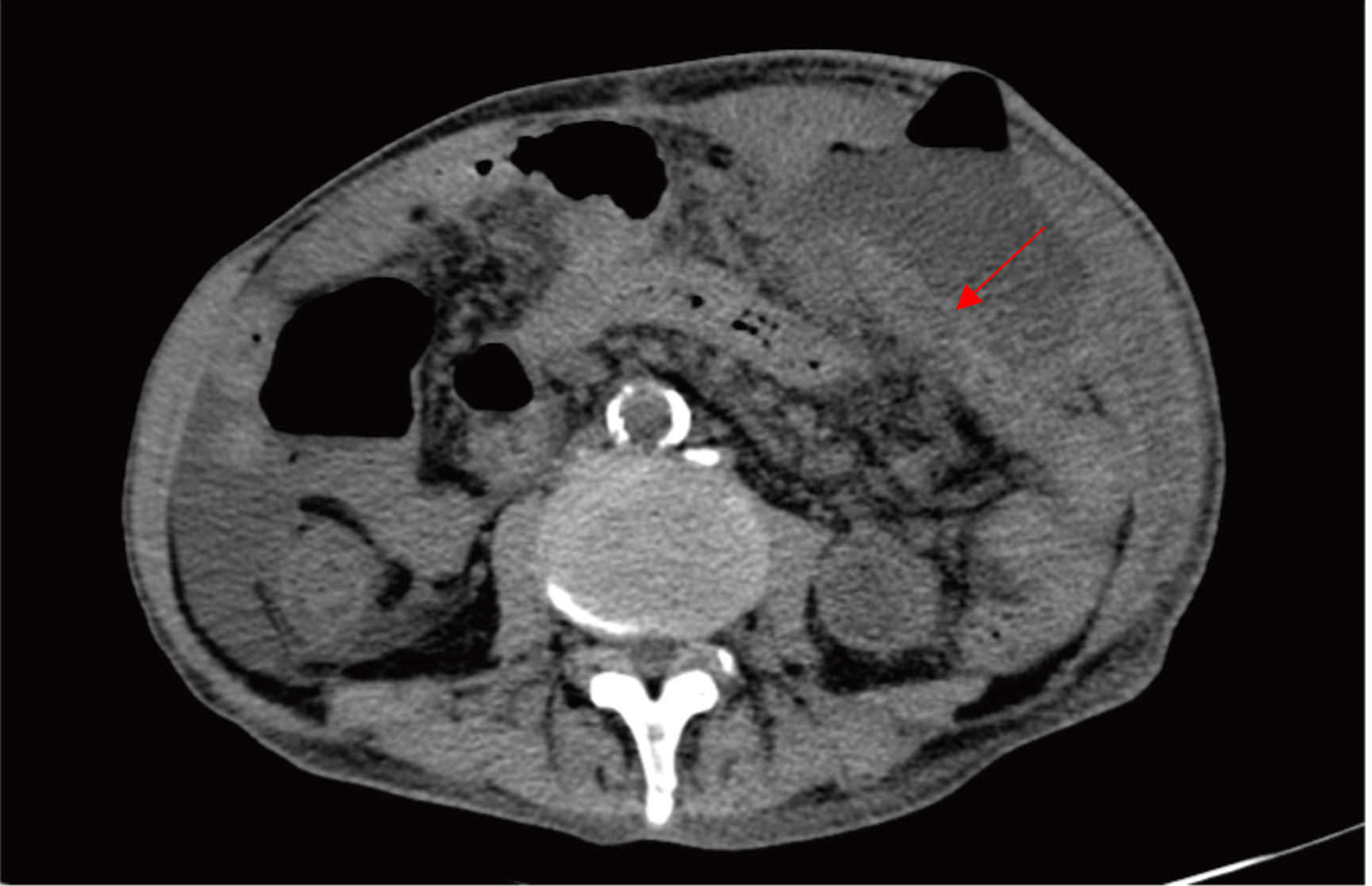

Moreover, abdominal computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed typical peritonitis changes. In addition, there was medium-sized fluid and gaseous content around the anastomotic orifice, suggesting inflammatory exudate and an encapsulated abscess (Figure 1).

Combined with his medical history, clinical presentation, and examination, severe intra-abdominal infection and shock were diagnosed. Therefore, we began to consider the occurrence of an anastomotic fistula.

Treatment started with rapid fluid resuscitation and anti-infection therapy. Moreover, bacterial culture was conducted on blood samples and wound abscesses. Due to his severe infection, the patient was empirically prescribed imipenem/cilastatin (0.5 g q6h) for 5 d, and patient symptoms were relieved significantly. While the blood culture result showed E.coli(+) which is sensitive to piperacillin/tazobactam. Therefore, the prescription was change to piperacillin/tazobactam (4.5 g q8h) until patient’s infection indicator return to normal. In addition to gastrointestinal decompression via a gastric tube, nutritional status was evaluated based on the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002[8,9]. The score was calculated to be 4, suggesting that the patient needed nutritional support. Therefore, we placed a peripherally inserted central catheter, and TPN was initiated via all-in-one supplementation in the first 72 h because of gastrointestinal dysfunction and sepsis. In addition, abscess puncture was performed under ultrasound localization, and a double-tube catheter was inserted for continuous irrigation and drainage.

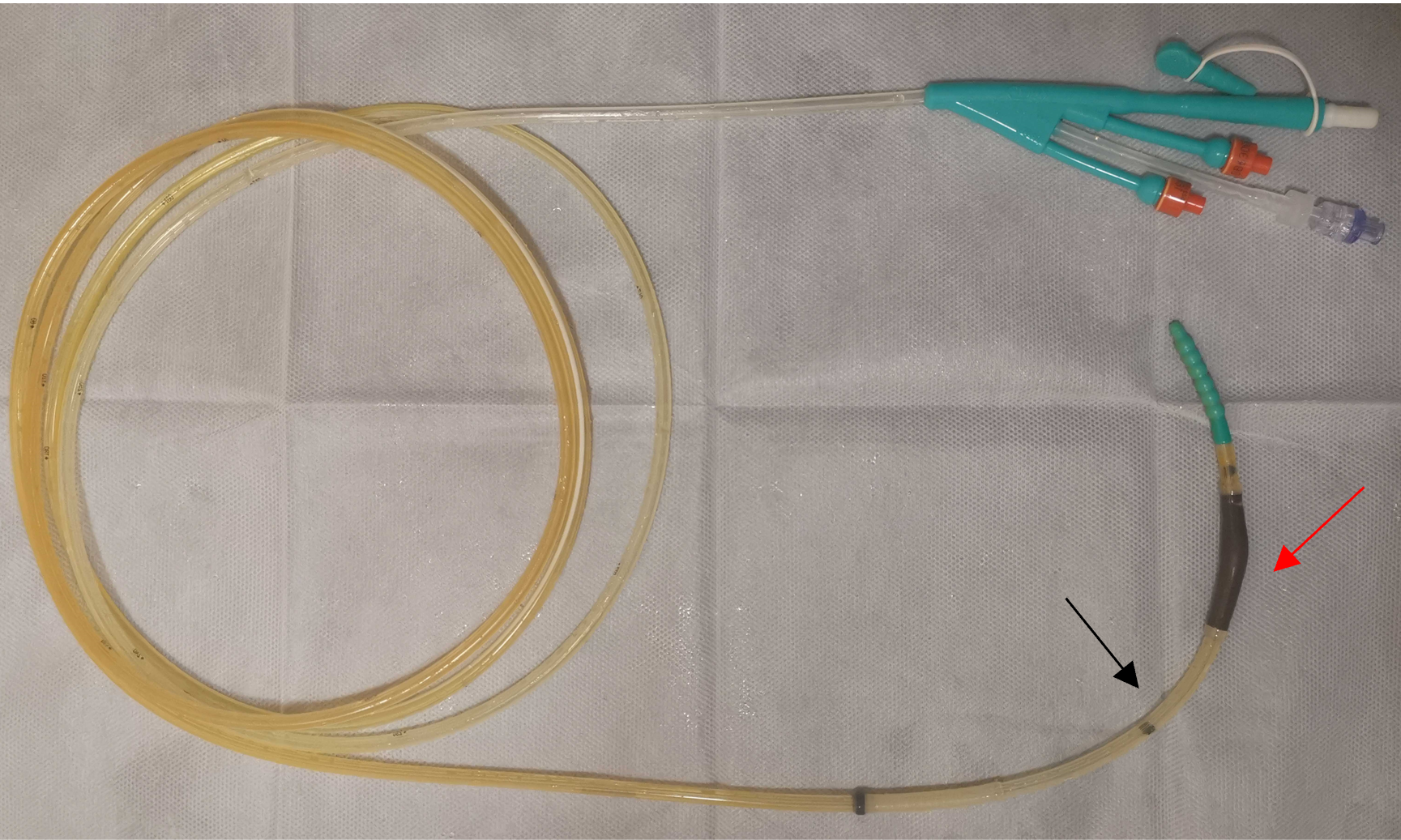

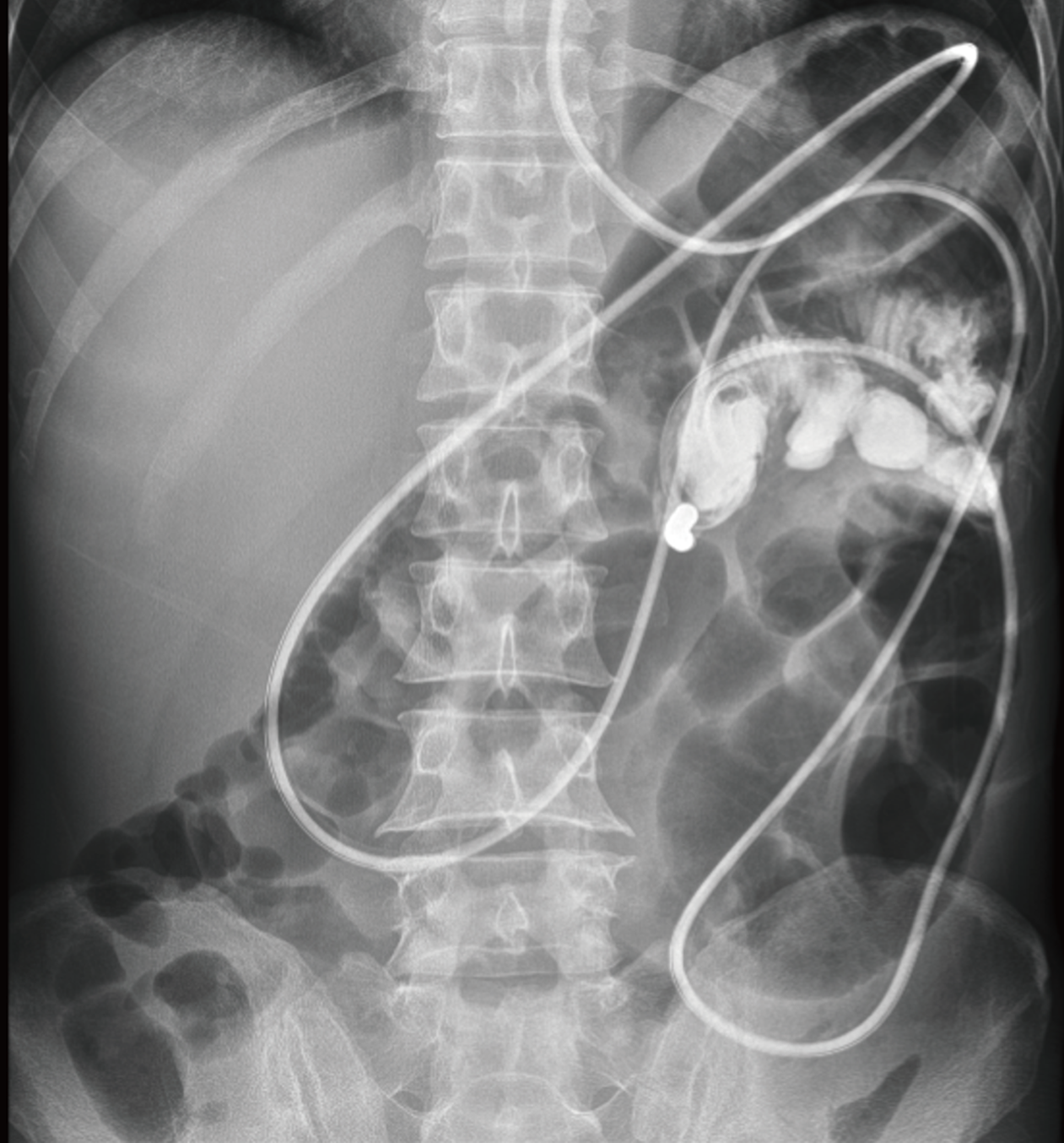

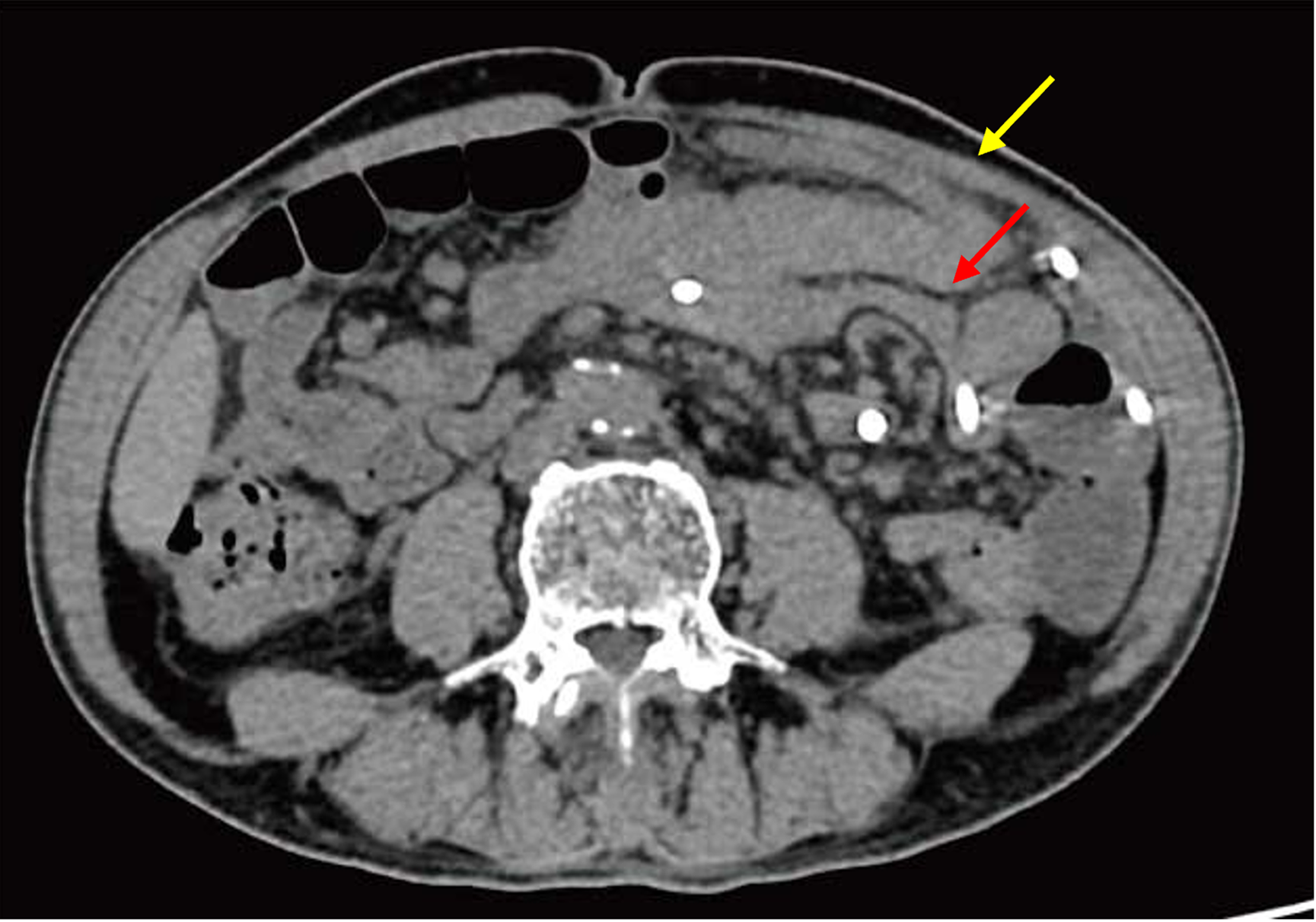

As the patient’s condition improved, we performed several examinations, including a fistulogram, endoscopy, and CT scans. The results suggested anastomotic leakage. Additionally, we measured the location of the fistula (Figure 2). To promote rehabilitation, we decided to place an intestinal obstruction catheter instead of a nasal jejunal tube through gastroscopy for subsequent early EN support in consideration of the anatomic position of the fistula and the inadequate length of the catheter. A three-metre long catheter with a diameter of 16 French (Fr) was used, ensuring that the catheter could be placed in the appropriate location (additional details of the catheter can be found in Figure 3). The obstruction catheter was initially placed in the upper jejunum, and we did not fix the distal end of the catheter, which allowed its proximal end to move forward via intestinal peristalsis. Next, we recorded the position of the catheter every day until it crossed the fistula by approximately 40 cm. After that, we conducted gastrointestinal imaging twice to confirm its position (Figure 4). EN support was initiated with 24 h of continuous infusion once the symptoms remitted. We modified the nutritional plan dynamically based on the patient’s tolerance and response. No complications, such as increasing fistula output, nutrient reflux, or symptoms, such as abdominal distension, nausea, or vomiting, were found during the treatment process involving the catheter.

A month later, the patient had fully adapted to the EN. Then, he started oral feeding. One week later, gastrointestinal imaging was performed to evaluate the intra-abdominal condition and healing of the fistula. The results showed that there was no sign of fistula or intra-abdominal infection (Figure 5). Finally, the patient recovered and was safely discharged. The fistula had spontaneously healed without surgical repair, and no special complications were observed during the follow-up examination six months later.

ECF can cause loss of the Succus entericus, dehydration, electrocyte, and acid-base disturbance[10,11]. Moreover, peritonitis and sepsis often occur due to intestinal mucosa damage[12]. Patients with chronic hypermetabolism and absorption dysfunction generally suffer from malnutrition, which can lead to cachexia and immunodeficiency. Therefore, nutritional support is an indispensable part of ECF treatment. Currently, TPN is still a preferable choice in the initial stage of ECF treatment for patients who have gastrointestinal dysfunction or contraindications to EN[13,14]. Complete intravenous nutritional administration of TPN can not only reverse patients' abnormal metabolic status but also prevent further nutritional deterioration and reduce the output of fistula drainage, which is the foundation of wound healing[6,15]. During treatment, carbohydrates should provide approximately 50% to 70% of the total energy intake to ensure a normal metabolic process. Studies have shown that, compared to patients with a fever less than 1000 kcal per day, those who received 1500-2000 kcal had a lower mortality rate and a greater rate of fistula healing[16]. Despite this, energy components still need individualized dynamic adjustment by monitoring clinical indicators. The nitrogen balance is a common indicator of the anabolic status for evaluating energy supply[17,18].

However, long-term TPN can lead to certain complications, such as metabolic disorders, PN-related liver disease, catheter-associated infection, and thrombosis[19,20]. It has been reported that long-term TPN damages innate intestinal immune function through the decreased secretion of immunoglobulins and a decrease in the proportion of lymphocytes. Although supplementation with glutamine can help relieve intestinal epithelium damage and maintain mucosal integrity, starting early EN support is a better option[21]. After the principle of ‘giving EN priority, PN as a supplement’ was put forward in 1978, many related studies have been performed[22]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that EN is an independent protective factor associated with fistula closure. Compared to PN, EN can maintain intestinal barrier function, prevent the incidence of endogenous infections, and alleviate symptoms such as liver injury and cholestasis. Additionally, EN is beneficial for intestinal immune function because it prevents intestinal mucosal atrophy, which is crucial for anastomosis. Therefore, choosing the right time to start EN is essential in ECF management. These findings suggested that patients' intestinal function improved when enterokinesia returned to normal and when anal exhaust occurred. Although TPN could be the better option in the early stage of ECF treatment, if the patient had the opportunity to use EN, we should manage to provide partial enteral nutrition. This transition stage is also called PN combined with EN. There are some common indicators that suggest starting EN support: (1) Recovery of gastrointestinal function and patients’ enteroparalysis relief (bowel sounds, movement return to normal); (2) Infection and electrolyte imbalance are both under effectively controlled; and (3) The anatomical definition of the fistula was confirmed, and the integrity of the residual intestine was restored. Usually, EN support starts with 100-250 mL amount of glucose-saline solution to allow patients’ digestive system to adapt. Then, switch to providing enteral nutritional emulsion while gradually reducing the partial amount of PN until the patient entirely relies on EN. During this period, patients’ abdominal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, distension, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea must be closely observed and evaluated to adjust the intake amount and infusion rate of enteral nutrition in a timely manner. However, due to variable ECF location, metabolic stress, and fistula output, there are individual demands for nutrition support. In this case, higher calorie and protein nutritional emulsions are preferred choices for the malnutrition and sepsis patient. In details, we firstly provide short-peptide-based enteral nutritional suspension (SP), which is conducive to absorption. Then gradually transit to total-protein-based enteral nutritional emulsion (TP) which provide high protein and energy for ECF patient up to 1500 mL, then about 200 mL enteral nutritional emulsion (TPF-T) which contain fibre is added as supplement.

For most patients with ECFs, Invasive procedures, such as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, due to its various surgical complications, is not the first choice. Nasogastric feeding is the preferred method. This approach is convenient for nursing management and decreases the risk of aspiration and vomiting caused by reflux. Therefore, nutritional support requires a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s status. It is imperative to restore intestinal integrity for early EN support. To date, a variety of methods have been developed. For proximal intestinal fistulas, a nasointestinal tube can be placed across the fistula to a sufficient length. Fibrin glue sealing is effective at restoring intestinal integrity in patients with multiple fistulas[23]. The application of the over-the-scope clip was reported to have an approximately 70% ECF closure rate[24]. However, for distal fistulas, there are no appropriate methods for EN administration. In this case, we developed a new application for intestinal obstruction catheters. The catheter was initially designed for bowel obstruction, and it could slowly move forward and pass through the obstruction position plane via intestinal peristalsis and the weight stack at the end. Gastrointestinal decompression can begin when it reaches obstructive sites. Therefore, we capitalized on this feature, allowing the catheter to pass completely through the fistula, and we could provide the patient with EN support. Additionally, continuous negative pressure drainage decreases digestive fluid efflux through the fistula. Excess nutrient solution can be easily removed, reducing the risk of abdominal contamination. Although we observed a transient increase in the output of the fistula in the early period of EN support, this issue can be addressed by extending the length of catheter placement and decreasing the infusion rate of the mixture. We believe that this approach is a safe and effective method for EN support. Early EN support alleviated patient hunger and accelerated the recovery process, leading to rapid healing of the fistula.

Early EN support is currently accepted as the best choice for ECF management[5]. Currently, an increasing number of materials and methods are being designed for different ECF classifications and include nasogastric tubes, nasojejunal tubes, gastrostomy tubes, enterostomy tubes, and jejunal feeding techniques. Excessive secretion of digestive fluid might cause an increased output of fistulas through the use of a nasogastric tube. The nasojejunal tube is still regarded as the first choice for enteral feeding. With the advancements in the material field, new technologies can gradually be applied to restore intestinal integrity. Following the principle of never using parenteral nutrition when enteral nutrition is possible, providing patient EN support as soon as possible and maximizing the utilization of intestinal function are important concepts for promoting the rapid recovery of ECFs. Therefore, clinicians should manage the development of individualized nutritional support plans for different patients. The TPN, combination of PN and EN, and EN support plans should be properly applied to promote patient recovery.

To summarize, we reported a case in which early EN support via an intestinal obstruction catheter was used for a lower enterocutaneous fistula. A catheter could be used for early enteral nutrition support in patients with lower ECFs.

| 1. | Schecter WP, Hirshberg A, Chang DS, Harris HW, Napolitano LM, Wexner SD, Dudrick SJ. Enteric fistulas: principles of management. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:484-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Whelan JF Jr, Ivatury RR. Enterocutaneous fistulas: an overview. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2011;37:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bleier JI, Hedrick T. Metabolic support of the enterocutaneous fistula patient. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:142-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kumar P, Maroju NK, Kate V. Enterocutaneous fistulae: etiology, treatment, and outcome - a study from South India. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:391-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kumpf VJ, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Diaz-Pizarro Graf JI, Hall AM, McKeever L, Steiger E, Winkler MF, Compher CW; FELANPE; American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. ASPEN-FELANPE Clinical Guidelines. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017;41:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Badrasawi MM, Shahar S, Sagap I. Nutritional management of enterocutaneous fistula: a retrospective study at a Malaysian university medical center. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Reintam Blaser A, Starkopf J, Alhazzani W, Berger MM, Casaer MP, Deane AM, Fruhwald S, Hiesmayr M, Ichai C, Jakob SM, Loudet CI, Malbrain ML, Montejo González JC, Paugam-Burtz C, Poeze M, Preiser JC, Singer P, van Zanten AR, De Waele J, Wendon J, Wernerman J, Whitehouse T, Wilmer A, Oudemans-van Straaten HM; ESICM Working Group on Gastrointestinal Function. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:380-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maciel LRMA, Franzosi OS, Nunes DSL, Loss SH, Dos Reis AM, Rubin BA, Vieira SRR. Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 Cut-Off to Identify High-Risk Is a Good Predictor of ICU Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z; Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:321-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1485] [Cited by in RCA: 1867] [Article Influence: 81.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ortiz LA, Zhang B, McCarthy MW, Kaafarani HMA, Fagenholz P, King DR, De Moya M, Velmahos G, Yeh DD. Treatment of Enterocutaneous Fistulas, Then and Now. Nutr Clin Pract. 2017;32:508-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lundy JB, Fischer JE. Historical perspectives in the care of patients with enterocutaneous fistula. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010;23:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fischer JE. The pathophysiology of enterocutaneous fistulas. World J Surg. 1983;7:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gefen R, Garoufalia Z, Zhou P, Watson K, Emile SH, Wexner SD. Treatment of enterocutaneous fistula: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:863-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parli SE, Pfeifer C, Oyler DR, Magnuson B, Procter LD. Redefining "bowel regimen": Pharmacologic strategies and nutritional considerations in the management of small bowel fistulas. Am J Surg. 2018;216:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Campos AC, Andrade DF, Campos GM, Matias JE, Coelho JC. A multivariate model to determine prognostic factors in gastrointestinal fistulas. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yanar F, Yanar H. Nutritional support in patients with gastrointestinal fistula. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2011;37:227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nordenström J, Askanazi J, Elwyn DH, Martin P, Carpentier YA, Robin AP, Kinney JM. Nitrogen balance during total parenteral nutrition: glucose vs. fat. Ann Surg. 1983;197:27-33. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Konstantinides FN. Nitrogen balance studies in clinical nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 1992;7:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li Y, Liu H. Application strategy and effect analysis of nutritional support nursing for critically ill patients in intensive care units. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang P, Sun H, Maitiabula G, Zhang L, Yang J, Zhang Y, Gao X, Li J, Xue B, Li CJ, Wang X. Total parenteral nutrition impairs glucose metabolism by modifying the gut microbiome. Nat Metab. 2023;5:331-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang X, Pierre JF, Heneghan AF, Busch RA, Kudsk KA. Glutamine Improves Innate Immunity and Prevents Bacterial Enteroinvasion During Parenteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39:688-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li J. Gastrointestinal fistula. Chin J Surg. 1978;4:214-217. |

| 23. | Wu X, Ren J, Gu G, Wang G, Han G, Zhou B, Ren H, Yao M, Driver VR, Li J. Autologous platelet rich fibrin glue for sealing of low-output enterocutaneous fistulas: an observational cohort study. Surgery. 2014;155:434-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang J, Da B, Diao Y, Qian X, Wang G, Gu G, Wang Z. Efficacy and safety of over-the-scope clips (OTSC®) for closure of gastrointestinal fistulas less than 2 cm. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:5267-5274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/