Published online Jul 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i19.3692

Revised: April 13, 2024

Accepted: May 14, 2024

Published online: July 6, 2024

Processing time: 157 Days and 21.9 Hours

Dietary fiber is essential for human health and can help reduce the symptoms of constipation. However, the relationship between dietary fiber and diarrhea is, poorly understood.

To evaluate the relationship between dietary fiber and chronic diarrhea.

This retrospective study was conducted using data from the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, conducted between 2005 and 2010. Participants over the age of 20 were included. To measure dietary fiber consumption, two 24-hour meal recall interviews were conducted. The independent relationship between the total amount of dietary fiber and chronic diarrhea was evaluated with multiple logistic regression and interaction analysis.

Data from 12829 participants were analyzed. Participants without chronic diarrhea consumed more dietary fiber than participants with chronic diarrhea (29.7 vs 28.5, P = 0.004). Additionally, in participants with chronic diarrhea, a correlation between sex and dietary fiber intake was present: Women who consume more than 25 g of dietary fiber daily can reduce the occurrence of chronic diarrhea.

Dietary fiber can reduce the occurrence of chronic diarrhea.

Core Tip: Dietary fiber is essential for human health. Among the many health advantages of dietary fiber include its ability to speed up intestinal transit, reduce blood sugar and cholesterol, and increase satiety. Based on numerous studies, a high-fiber diet can lower the incidence of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperuricemia, cardiovascular illnesses, and cancer. Supplementing diet with fiber is advised in a number of chronic constipation treatment regimens. The symptoms of diarrhea include loose or watery stools and an increase in the frequency of bowel movements. It is caused by changes in the ion absorption and water balance of intestinal cells. Dietary fiber has been demonstrated in animal trials to alleviate diarrhea, decrease intestinal motility, and greatly boost the intestinal mucosa's release of secretory immunoglobulin A. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because, currently, there is no recommended dietary fiber intake for patients with chronic diarrhea. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the correlation between dietary fiber consumption and chronic diarrhea via a comprehensive sample analysis using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database.

- Citation: Wang L, Li Y, Zhang YJ, Peng LH. Relationship between dietary fiber intake and chronic diarrhea in adults. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(19): 3692-3700

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i19/3692.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i19.3692

Dietary fiber consists of carbohydrate polymers primarily found in grains, vegetables, fruits, and legumes. It is indigestible and cannot be absorbed by the small intestine. Instead, it passes into the large intestine, where it is fermented by the intestinal flora. The gut microbiota and microbial metabolic processes can be impacted by the fermentation process[1]

Dietary fiber has numerous health benefits, including accelerating intestinal transit speed, reducing blood glucose and cholesterol levels, and increasing satiety[2]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the protective effects of a high-fiber diet against type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperuricemia, cardiovascular disease, and cancer[3-9]. In the United States and Europe, it is currently recommended that adult men and women consume 30-35 and 25-32 g of daily fiber, respectively[10].

Multiple treatment guidelines for chronic constipation also recommend supplementing with dietary fiber[11,12]. Diarrhea is defined as an increase in the frequency of stools and loose or watery stools, which can lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. It is caused by modifications to the intestinal cellular water balance and ion absorption, which lead to increased secretion and decreased absorption of fluid and electrolytes, as well as a shortened gastrointestinal transit time. An insufficient transit time results in poor absorption of intestinal water, leading to thin stools[13]. An experiments have shown that fiber can alleviate diarrhea, reduce intestinal motility, and significantly increase the release of mucosal secretory immunoglobulin A[14]. Meanwhile, studies have shown that increasing dietary fiber intake may increase the abundance of microbeneficial bacteria in the gut of healthy adults, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii[15]. Therefore, in a thorough sample analysis, we aimed to evaluate the relationship between dietary fiber consumption and chronic diarrhea by utilizing the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics annually conducts NHANES, a nationally representative survey, which is released every two years. A sophisticated, multi-phase, stratified cluster sampling technique is used to randomly pick participants. Interviews are used to gather data. The National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board has authorized NHANES, and participants sign an informed consent form prior to interview.

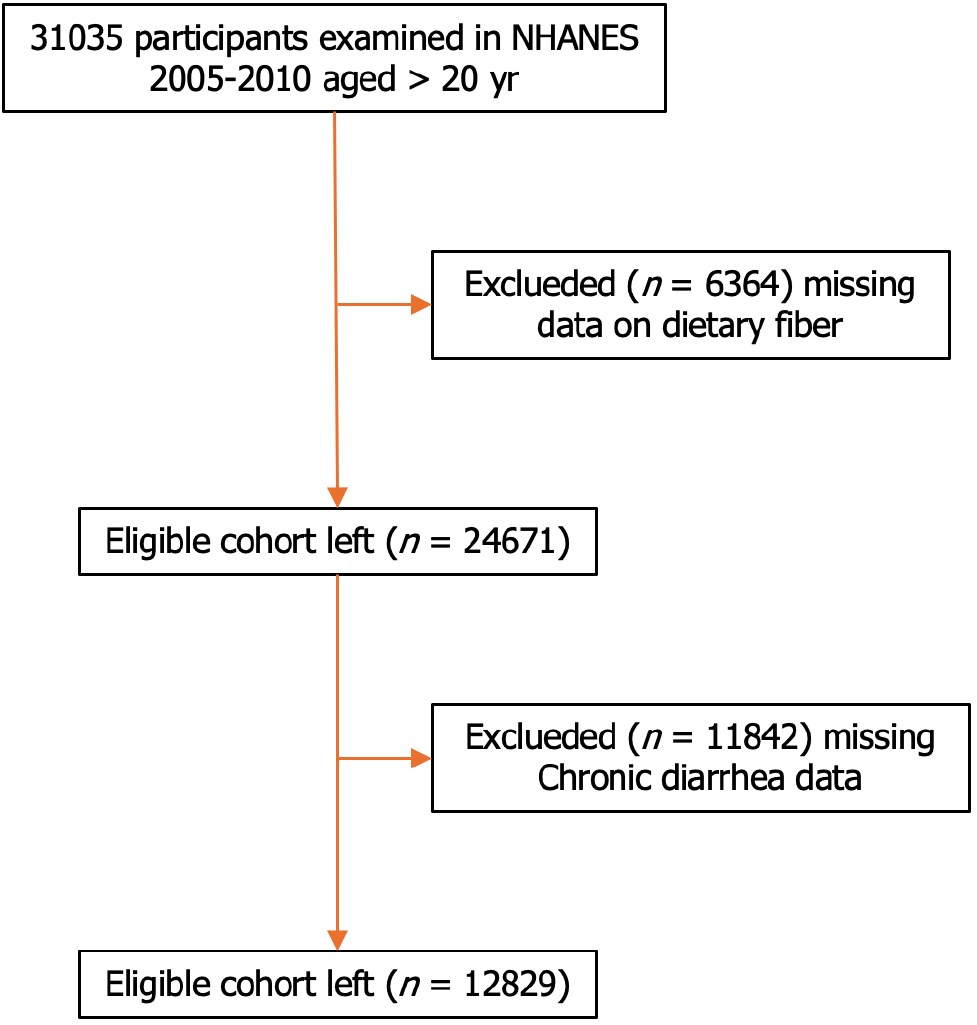

This analysis combined cross-sectional data from three NHANES cycles (2005-2006, 2007-2008, and 2009-2010). Analysis was restricted to 31,035 participants aged ≥ 20. Individuals missing information on fiber intake and chronic diarrhea were excluded.

The manipulated variable in this study was dietary fiber consumption, determined using two 24-hour food recall interviews. The first interview was done in a mobile testing center, while the second interview took place via telephone within a period of 3–10 d. The estimation of dietary fiber intakes was conducted using the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies provided by the United States Department of Agriculture. The identification of dietary fiber sources was conducted through the utilization of food codes. The mean consumption reported in the two interviews was calculated and used in the analysis.

The NHANES Gastrointestinal Health Questionnaire was used to identify participants with chronic constipation and diarrhea. Participants were shown a card with a colored picture and a description of the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS). They were then asked to identify the number corresponding to the type of stool usually or most commonly associated with their bowel movements in the past 12 months. During the study, participants were questioned about their weekly bowel movements as well as the frequency of diarrhea and constipation in the past 12 months. Chronic diarrhea was classified as BSFS type 6 (soft, mushy stool with defined edges) or type 7 (watery, no solid pieces) and more than 21 weekly bowel movements, or diarrhea more than twice weekly in the past year.

This study also considered potential confounding variables. During the in-home interviews, participants self-reported their age, gender, educational attainment, marriage history, poverty income ratio, and body mass index (BMI). In addition, race was categorized as non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican-American, other. Smoking was classified in participants that reported a minimum of 100 cigarettes throughout their lifetime. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure equal to or greater than 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure equal to or greater than 90 mmHg, or self-reported. Diabetes was defined as a hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%. Participants who reported consuming at least 12 alcoholic drinks per year were classified as alcohol drinkers.

Continuous variables are represented with means and standard deviations, while categorical variables are described with frequencies and percentages. For normally distributed data, T-tests were used to compare the means of continuous variables between the chronic diarrhea group and those without chronic diarrhea. Alternatively, non-parametric tests were used for non-normally distributed data. Logistic regression modeling was employed to examine the relationship between total fiber consumption and the occurrence of chronic diarrhea. Dietary fiber consumption was classified into four quartiles: T1 (< 25%), T2 (≥ 25% to 50%), T3 (≥ 50% to 75%), and T4 (≥ 75%). The reference value was the lowest quartile (T1). Model 1 was not adjusted. Sex, age, race and BMI were adjusted in model 2. Model 3 was adjusted by sex, age, race, BMI, educational level, marital status, diabetes and hypertension. Subsequently, a stratified analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between fiber consumption and chronic diarrhea, taking into account variables such as sex, age, BMI, and hypertension. Logistic regression models were employed to determine odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P value less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using Empower Stats (http://www.empowstats.com) and R software version 3.4.3 (http://www.r-project.org/).

After exclusion of participants with missing data for fiber intake (n = 6364) and chronic diarrhea (n = 11842), data from 12829 participants were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Chronic diarrhea was reported by 1968 participants (15.34%). Baseline characteristics between the chronic and non-chronic diarrhea groups are shown in Table 1. The chronic diarrhea group had a lower dietary fiber intake, a higher proportion of women, older age, a higher BMI, a higher proportion of Hispanic ethnicity, and a higher number of smokers than the non-chronic diarrhea group (P < 0.01). In addition, the chronic diarrhea group had more participants with diabetes and hypertension than the non-chronic diarrhea group. There was statistical significance (P < 0.05). However, marital status and alcohol use were not significantly different between the groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variables | No chronic diarrhea (n = 10861) | Chronic diarrhea (n = 1968) | Statistic | P value | |

| Dietary fiber, median (25th-75th percentiles) | 29.7 (21.0-41.2) | 28.5 (20.0-40.2) | 8.458 | 0.004 | |

| Dietary fiber T | 10.822 | 0.013 | |||

| Dietary fiber T1 | 2650 (24.4) | 546 (27.7) | |||

| Dietary fiber T2 | 2698 (24.8) | 485 (24.6) | |||

| Dietary fiber T3 | 2771 (25.5) | 468 (23.8) | |||

| Dietary fiber T4 | 2742 (25.2) | 469 (23.8) | |||

| Gender | 5.618 | 0.018 | |||

| Man | 5271 (48.5) | 898 (45.6) | |||

| Female | 5590 (51.5) | 1070 (54.4) | |||

| Age | 49.6 ± 18.1 | 51.6 ± 17.0 | 21.419 | < 0.001 | |

| BMI | 28.9 ± 6.5 | 30.4 ± 7.4 | 81.543 | < 0.001 | |

| Race | 16.981 | < 0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic whites | 1894 (17.4) | 377 (19.2) | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 5558 (51.2) | 968 (49.2) | |||

| Mexican Americans | 2146 (19.8) | 345 (17.5) | |||

| Hispanics and other races | 1263 (11.6) | 278 (14.1) | |||

| Education | Fisher | < 0.001 | |||

| Below high school | 2821 (26) | 638 (32.4) | |||

| High school diploma or equivalent | 2594 (23.9) | 478 (24.3) | |||

| University or above | 5437 (50.1) | 850 (43.2) | |||

| Marriage | 0.934 | 0.334 | |||

| Married | 9156 (84.3) | 1676 (85.2) | |||

| Unmarried | 1699 (15.7) | 291 (14.8) | |||

| Poverty-income ratio | 54.58 | < 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 1.30 | 2788 (27.6) | 643 (35.6) | |||

| 1.31-3.5 | 3941 (39) | 675 (37.4) | |||

| > 3.5 | 3384 (33.5) | 489 (27.1) | |||

| Smoke | 21.73 | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 2221 (20.4) | 469 (23.8) | |||

| No | 2812 (25.9) | 552 (28) | |||

| Dink | Fisher | 0.427 | |||

| Yes | 7710 (71) | 1406 (71.4) | |||

| No | 3146 (29) | 560 (28.5) | |||

| Diabetes | 21.766 | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1034 (9.5) | 254 (12.9) | |||

| No | 9459 (87.1) | 1643 (83.5) | |||

| Hypertension | Fisher | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 4553 (41.9) | 982 (49.9) | |||

| No | 6307 (58.1) | 984 (50) | |||

To examine the association between chronic diarrhea and fiber intake, the researchers divided the total fiber intake into four quartiles (T1, T2, T3, and T4) (Table 2). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted. Based on the results of the univariate analysis, chronic diarrhea was significantly associated with dietary fiber intake, sex, age, BMI, ethnicity, education level, income, hypertension, and diabetes (all P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Group | n | Mean (g) | Median (g) | |

| Fiber | T1 | 3196.0 | 14.985 | 15.8 |

| T2 | 3183.0 | 25.031 | 25.0 | |

| T3 | 3239.0 | 34.643 | 34.4 | |

| T4 | 3211.0 | 55.491 | 51.0 |

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Dietary fiber T1 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Dietary fiber T2 | 0.872 (0.763-0.997) | 0.0452 |

| Dietary fiber T3 | 0.820 (0.717-0.938) | 0.0038 |

| Dietary fiber T4 | 0.830 (0.726-0.950) | 0.0067 |

| Male | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Female | 1.124 (1.020-1.237) | 0.0178 |

| Age | 1.006 (1.004-1.009) | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 1.031 (1.024-1.038) | < 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic whites | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.875 (0.768-0.996) | 0.0439 |

| Mexican Americans | 0.808 (0.689-0.946) | 0.0083 |

| Hispanics and other races | 1.106 (0.932-1.311) | 0.2477 |

| Education | 0.832 (0.787-0.88) | < 0.001 |

| Married | 1 (Ref.) | |

| Unmarried | 0.936 (0.818-1.071) | 0.3338 |

| Poverty-income ratio ≤ 1.30 | 1(Ref) | |

| Poverty-income ratio 1.31-3.5 | 0.743 (0.66-0.836) | < 0.001 |

| Poverty-income ratio > 3.5 | 0.627 (0.551-0.712) | < 0.001 |

| Smoke | 0.93 (0.812-1.064) | 0.2895 |

| Dink | 0.976 (0.878-1.086) | 0.6558 |

| Diabetes | 1.414 (1.221-1.638) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.382 (1.256-1.522) | < 0.001 |

A multifactorial logistic regression analysis was carried out to investigate the correlation between dietary fiber intake and chronic diarrhea. The results in unadjusted Model 1 showed that compared to the lowest quartile (T1) of dietary fiber intake, T2 (OR: 0.87; 95%CI: 0.76–1.00), T3 (OR: 0.82; 95%CI: 0.72–0.94), and T4 (OR: 0.83; 95%CI: 0.73–0.95) were all associated with chronic diarrhea. In Model 2, adjusted for sex, age, race, and BMI, the correlation between T2, T3, and T4 and chronic diarrhea remained stable. In Model 3, the variables of sex, age, race, BMI, level of education, marriage history, diabetes, and hypertension were included as covariates, and T3 dietary fiber intake remained associated with chronic diarrhea (OR: 0.85; 95%CI: 0.74–0.98) (Table 4).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

| Variable | n (%) | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Dietary fiber T1 | 546 (17.1) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | 1 (Ref.) | |||

| Dietary fiber T2 | 485 (15.2) | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) | 0.045 | 0.85 (0.74-0.97) | 0.019 | 0.88 (0.77-1.01) | 0.062 |

| Dietary fiber T3 | 468 (14.4) | 0.82 (0.72-0.94) | 0.004 | 0.82 (0.71-0.94) | 0.004 | 0.85 (0.74-0.98) | 0.026 |

| Dietary fiber T4 | 469 (14.6) | 0.83 (0.73-0.95) | 0.007 | 0.83 (0.73-0.96) | 0.011 | 0.89 (0.77-1.03) | 0.108 |

| t test | 1968 (15.3) | 0.94 (0.9-0.98) | 0.004 | 0.94 (0.9-0.98) | 0.009 | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.092 |

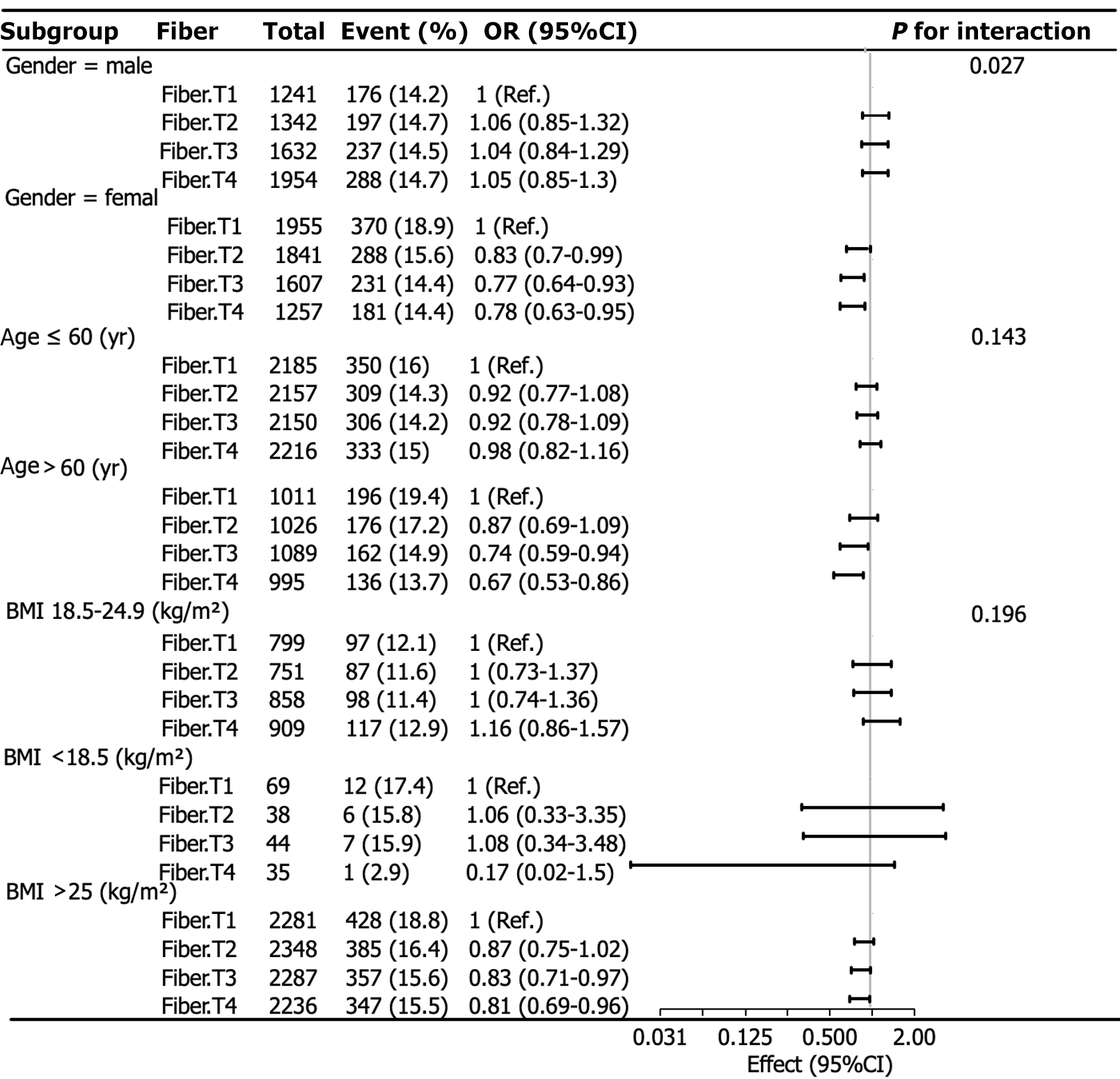

Logistic subgroup analysis was performed using the dietary fiber quartiles as categorical variables. Race, educational level, income, and marital status were used as covariates, whereas sex, age, and BMI were used as grouping variables. The results are presented as forest plots (Figure 2).

The subgroup analysis of dietary fiber quartiles showed a clear interaction between sex and the link with fiber intake and chronic diarrhea (P = 0.027). Among female participants, there was a meaningful link between fiber intake and chronic diarrhea. Compared with T1, the lowest quartile of fiber intake, T2, T3, and T4 had a lower risk of chronic diarrhea [(OR: 0.83; 95%CI: 0.70-0.99), (OR: 0.77; 95%CI: 0.64-0.93), and (OR: 0.78; 95%CI: 0.63-0.95), respectively]. A higher consumption of dietary fiber was found to be associated with a reduced risk of chronic diarrhea among female participants. Nevertheless, the analysis did not reveal any substantial correlations between the intake of dietary fiber and the occurrence of chronic diarrhea among males (P > 0.05).

This study aimed to examine the correlation between dietary fiber consumption and the prevalence of chronic diarrhea, utilizing a comprehensive dataset. Our study revealed that those with non-chronic diarrhea had higher dietary fiber intakes than those with chronic diarrhea. Additionally, we found that the dietary fiber intake was a protective factor in patients with chronic diarrhea. The dietary fiber intake was categorized into four distinct groups, and it was the risk of chronic diarrhea was diminished with higher dietary fiber intake in comparison to the group with the lowest intake.

Consuming > 25 gm of dietary fiber daily can help prevent diarrheal symptoms[16]. A significant correlation was observed between dietary fiber consumption of and the occurrence of chemotherapy-induced diarrhea in individuals diagnosed with colon cancer[17]. Additionally, the type of dietary fiber may have varying effects on chronic diarrhea. For instance, an animal study demonstrated that dietary fibers with low hydratable properties could worsen diarrhea in weaned piglets[18].

Several possible mechanisms for variable interactions between dietary fiber and chronic diarrhea exist. The viscosity of dietary fiber refers to its ability to form a gel. Soluble fiber thickens or forms a gel when it comes into contact with liquids, aiding stool formation. Dietary fiber can retain excess fluid in the intestinal lumen, increasing the viscosity of feces and improving stool consistency in diarrhea[19]. Cross-sectional studies of the global population have shown that an increased dietary fiber intake is associated with an increase in gut microbiota diversity[20], and a dietary regimen deficient in dietary fiber has the potential to diminish the richness and variety of gut bacteria[21]. Simultaneously, the human gut microbiota produces numerous enzymes specific to dietary fibers[22], which facilitate the m metabolism of dietary fibers into various short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), that are associated with the gut microbiota[21]. High fiber intake results in increased levels of SCFAs after fermentation. This creates a favorable growth environment for beneficial symbiotic bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, which lowers intestinal pH by producing lactic acid. This promotes the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria, including butyrate-producing bacteria. SCFAs can also help maintain mucosal integrity by stimulating regulatory T cells, regulating inflammation and epithelial proliferation, and suppressing the excessive growth of pathogens through positive immune modulation, which can improve diarrhea[13,23]. The relationship between chronic diarrhea and dietary fiber has been associated with the function of the gut microbiota and its metabolites.

Our research indicates a sex-dependent negative association between dietary fiber consumption and chronic diarrhea. A negative link was observed between dietary fiber consumption and chronic diarrhea in female participants, but no significant correlation was detected in male participants. This sex-dependent effect may be attributed to the influence of dietary fiber on estrogen metabolism[24]. There were significant differences between males and females in transit time, stool volume, and bile acid excretion when they consumed the same amount of fiber. Men have higher fecal fiber excretion than women, and women often digest more fiber than men. This finding is consistent with men having a lower degree of colonic fermentation than women and provides additional evidence for the impact of sex differences on intestinal function[25]. There may be a differential effect of dietary fiber on males compared to females. In the male population, a substantial dietary fiber intake has been observed to serve as a preventive factor against the recurrence of colorectal adenomas. However, no statistically significant benefit has been identified in females[26]. The role of sex in the correlation between dietary fiber intake and diarrhea requires more research.

The strength of this study lies in its use of data from a large, nationally representative cohort, including 12829 samples collected between 2005 and 2010. This enabled more comprehensive and reliable results. The study also accounted for interactions between influencing factors and applied stratified analysis to identify the interaction effect of sex on the association between dietary fiber intake and chronic diarrhea. However, this study had limitations. First, the NHANES database is a cross-sectional study, and causal inferences cannot be established. Second, this study did not distinguish between insoluble and soluble dietary fibers. Third, the potential influence of all relevant chronic diseases and other unmeasured confounding factors cannot be excluded. Therefore, further longitudinal studies are warranted.

Dietary fiber may provide benefits for patients with chronic diarrhea, and these benefits may vary depending on sex. Further research is necessary to understand the effect of sex on dietary fiber intake and chronic diarrhea. Additionally, a causal link should be established with longitudinal studies, which could also clarify the role of other confounding factors.

| 1. | Artale S, Grillo N, Lepori S, Butti C, Bovio A, Barzaghi S, Colombo A, Castiglioni E, Barbarini L, Zanlorenzi L, Antonelli P, Caccialanza R, Pedrazzoli P, Moroni M, Basciani S, Azzarello R, Serra F, Trojani A. A Nutritional Approach for the Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aubertin-Leheudre M, Gorbach S, Woods M, Dwyer JT, Goldin B, Adlercreutz H. Fat/fiber intakes and sex hormones in healthy premenopausal women in USA. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;112:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Buil-Cosiales P, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ruiz-Canela M, Díez-Espino J, García-Arellano A, Toledo E. Consumption of Fruit or Fiber-Fruit Decreases the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in a Mediterranean Young Cohort. Nutrients. 2017;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen S, Hao M, Zhang L. Antidiarrheal Effect of Fermented Millet Bran on Diarrhea Induced by Senna Leaf in Mice. Foods. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | El Kaoutari A, Armougom F, Gordon JI, Raoult D, Henrissat B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:497-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 892] [Cited by in RCA: 1221] [Article Influence: 93.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey WD. Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:718-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Frazier TH, DiBaise JK, McClain CJ. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, obesity-induced inflammation, and liver injury. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:14S-20S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fuller S, Beck E, Salman H, Tapsell L. New Horizons for the Study of Dietary Fiber and Health: A Review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2016;71:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gastrointestinal Dynamics Group; Gastroenterology Branch; Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for primary diagnosis and treatment of chronic diarrhea]. Chin J Gen Pract. 2020;19:973-982. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Huang S, Cui Z, Hao X, Cheng C, Chen J, Wu D, Luo H, Deng J, Tan C. Dietary fibers with low hydration properties exacerbate diarrhea and impair intestinal health and nutrient digestibility in weaned piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2022;13:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jacobs ET, Lanza E, Alberts DS, Hsu CH, Jiang R, Schatzkin A, Thompson PA, Martínez ME. Fiber, sex, and colorectal adenoma: results of a pooled analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:343-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kamarul Zaman M, Chin KF, Rai V, Majid HA. Fiber and prebiotic supplementation in enteral nutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5372-5381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kranz S, Dodd KW, Juan WY, Johnson LK, Jahns L. Whole Grains Contribute Only a Small Proportion of Dietary Fiber to the U.S. Diet. Nutrients. 2017;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lampe JW, Fredstrom SB, Slavin JL, Potter JD. Sex differences in colonic function: a randomised trial. Gut. 1993;34:531-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin D, Peters BA, Friedlander C, Freiman HJ, Goedert JJ, Sinha R, Miller G, Bernstein MA, Hayes RB, Ahn J. Association of dietary fibre intake and gut microbiota in adults. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:1014-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Liu T, Feng P, Wang C, Ojo O, Wang YY, Wang XH. Effects of dietary fibre on enteral feeding intolerance and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2023;74:103326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Paquette IM, Varma M, Ternent C, Melton-Meaux G, Rafferty JF, Feingold D, Steele SR. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:479-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Segata N. Gut Microbiome: Westernization and the Disappearance of Intestinal Diversity. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R611-R613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Singh V, Yang J, Chen TE, Zachos NC, Kovbasnjuk O, Verkman AS, Donowitz M. Translating molecular physiology of intestinal transport into pharmacologic treatment of diarrhea: stimulation of Na+ absorption. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sonnenburg ED, Smits SA, Tikhonov M, Higginbottom SK, Wingreen NS, Sonnenburg JL. Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature. 2016;529:212-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 965] [Cited by in RCA: 1234] [Article Influence: 123.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stephen AM, Champ MM, Cloran SJ, Fleith M, van Lieshout L, Mejborn H, Burley VJ. Dietary fibre in Europe: current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutr Res Rev. 2017;30:149-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sun B, Shi X, Wang T, Zhang D. Exploration of the Association between Dietary Fiber Intake and Hypertension among U.S. Adults Using 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines: NHANES 2007⁻2014. Nutrients. 2018;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sun Y, Sun J, Zhang P, Zhong F, Cai J, Ma A. Association of dietary fiber intake with hyperuricemia in U.S. adults. Food Funct. 2019;10:4932-4940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Veronese N, Solmi M, Caruso MG, Giannelli G, Osella AR, Evangelou E, Maggi S, Fontana L, Stubbs B, Tzoulaki I. Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AF. Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J Nutr. 2008;138:439-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yao B, Fang H, Xu W, Yan Y, Xu H, Liu Y, Mo M, Zhang H, Zhao Y. Dietary fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose-response analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:79-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/