INTRODUCTION

Splenic hamartoma (SH) is a rare, benign vascular proliferation and is mostly found incidentally on abdominal images, at surgery, or at autopsy. These lesions vary in size, ranging from a few millimeters to 20 cm. SHs have also been referred to as splenomas, spleen within a spleen, posttraumatic scars, fibrotic nodules, tumor-like congenital malformations, and hyperplastic nodules. The first case was described by Rokitansky in 1861 and about 200 cases have been reported so far[1-3]. The incidence varies according to the results of different studies, ranging from 0.024% to 0.13% in autopsy specimens[4,5] and 0.17% to 9.7% in spleens of patients who underwent splenectomy[4,6]. However, the frequency of these lesions could be underestimated due to the splenic fragmentation that is performed as a way to ease extraction in laparoscopic splenectomy (LS)[6].

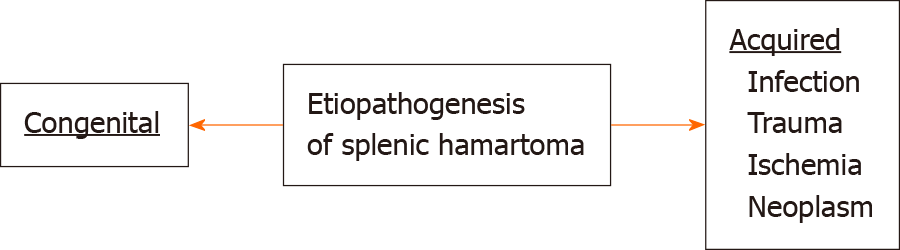

The etiopathogenesis of SH is not clear. While it is considered a congenital malformation by some authors, others claim that it might be an acquired proliferative process, being a neoplasm or developing as a response to trauma, infection, or ischemia (Figure 1)[7-9].

Figure 1 Possible etiopathogenesis of splenic hamartoma.

SH may be a diagnostic challenge because it is often asymptomatic or presents with non-specific symptoms and has no pathognomonic radiological appearance. Therefore, histopathological analysis represents the cornerstone of correct diagnosis[2,10,11].

These lesions may be identified in all age groups[2], with only about 20% of cases occurring in children[12]. Some clinical features differ between adult patients and children with SH[2,13]. We present a comprehensive overview of SHs in children by analyzing all the cases presented in the literature and reporting our case of an 8-year-old male with SH.

CASE REPORT OF AN 8-YEAR-OLD MALE WITH SH

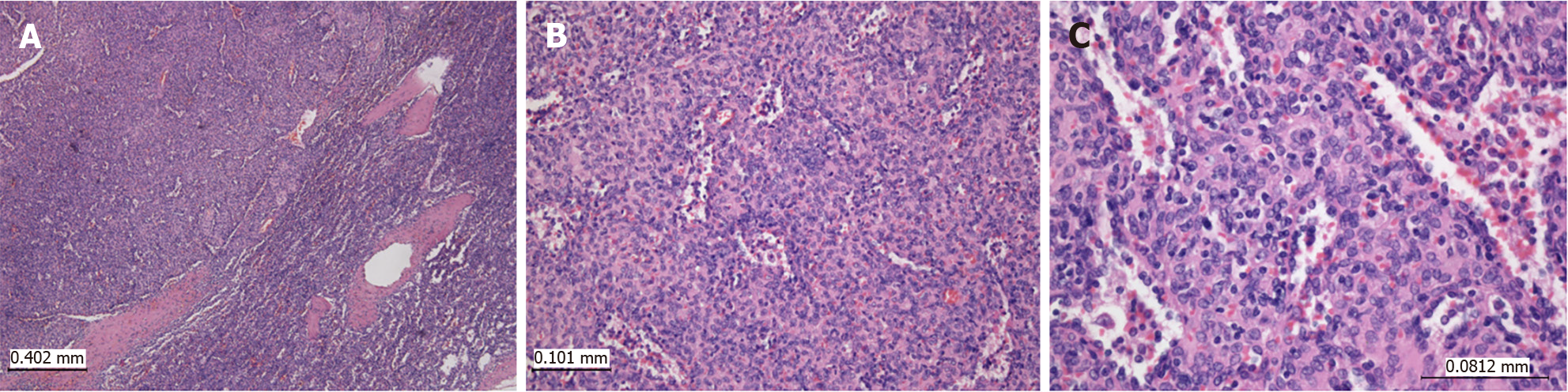

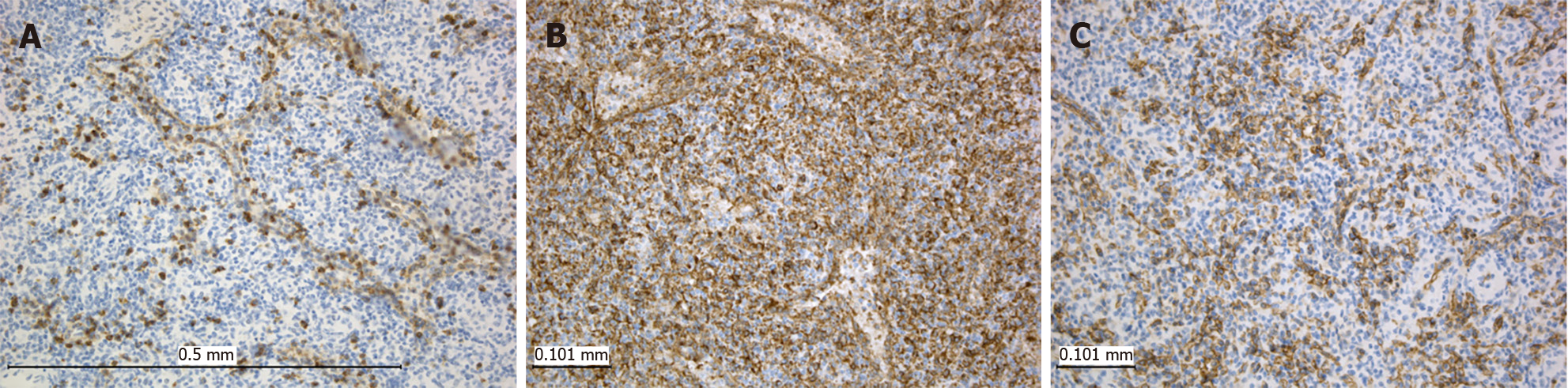

An 8-year-old male complained of intermittent pain in the left hypochondrium. His other past medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination showed no abnormalities, and laboratory blood analyses were within reference ranges. An abdominal ultrasound examination revealed an oval-shaped, clearly defined, slightly hypoechoic lesion (36 mm in diameter) in the lower pole of the spleen, with discrete posterior amplification. A complete removal of the lesion was achieved by partial splenectomy (PS). Grossly, the resected part of the spleen was 7.5 cm × 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm. On the cut surface, there was a 2.7 cm × 2.5 cm nodule, lighter than the surrounding normal splenic tissue (Figure 2). Histopathological examination revealed a nodular mass compressing the surrounding splenic parenchyma. The mass was composed of disorganized vascular channels lined by inconspicuous endothelial cells. No lymphoid follicles were detected in the lesion. Moreover, there was no atypia, mitotic activity, or necrosis (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of sinusoidal lining cells showed positive staining for CD8, CD31, and CD34 antigens and negativity for CD21 antigen (Figure 4). All this led to a diagnosis of SH. After 5 years of follow-up, the patient was doing well.

Figure 2 Gross appearance of splenic hamartoma.

A nodular circumscribed unencapsulated lesion is visible on the cross-section, representing splenic hamartoma.

Figure 3 Microscopic images of the splenic hamartoma.

A: Splenic hamartoma adjacent to normal splenic parenchyma was observed in the upper left of the panel, and compressed splenic parenchyma was observed in the lower right [hematoxylin and eosin (HE) × 50]; B: The lesion was composed of disorganized vascular channels lined by endothelial cells without significant cytological atypia (HE × 200); C: No mitosis or atypical cells were observed (HE × 400).

Figure 4 Immunohistochemical staining of the splenic hamartoma.

A: CD8 was positive in the lining cells of vascular channels and in rare lymphocytes (× 200); B: Strong staining for CD31 was observed in the lesion (× 200); C: The lining cells of sinus-like spaces in the hamartoma were immunoreactive for CD34 (× 200).

LITERATURE SEARCH

A literature search was performed via the PubMed database (www.pubmed.gov), Google Scholar (www.scholar.google.com), and the Cochrane Database up to 2023, using the following terms: “splenoma”; “hamartoma”; “spleen”; “masses”; “lesion” and “children”. Data were collected on age, sex, number, size, and location of hamartomatous nodules, clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory findings, imaging, indication for surgery, type of operation, and outcomes. The search revealed 47 cases described as SH in children[5,6,8,11-33].

All the cases analyzed in this review were diagnosed with SH by histopathological examination. A report by Raouani et al[34] was excluded due to a lack of histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis of SH. Data on all included cases found in the literature (46 patients), as well as on our case, are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data in some cases were incomplete because they were extracted from an abstract or cited text without having insight into the entire original article. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL FEATURES OF PEDIATRIC PATIENTS WITH SHS

The age data were available for 42 patients. Among them, the mean age was 8.3 years (range: 0.4-18.0 years). Sex data were available for the 42 patients (18 females and 24 males) and showed no significant difference in SH occurrence between the sexes. Thirty-five patients had solitary nodule whereas ten patients had multiple nodules, indicating the frequency of patients presenting with a solitary lesion was 78% (35/45). For 2 patients, there were no data regarding the number of nodules. The previously reported share of cases presenting with a single SH in adults was 55.5% in one study[35] and 88.9% in another[29]. The size of SH in children varied from a few millimeters to 18 cm in diameter[15,20]. Unlike the adult population, in which a higher frequency of large lesions was observed in female patients[4,9,36], there was no difference in SH size between males and females in our analysis of pediatric cases.

Approximately 80% of SH cases in adults are asymptomatic[37]. However, larger lesions may cause abdominal discomfort and pain, symptoms of compression on surrounding structures, or may be associated with hypersplenism. Although SHs are less common in the pediatric population compared with the adult population, the percentage of affected children having symptoms was higher than in adult patients[8,13]. In this study, different data regarding clinical presentation were available for 34 children. Over 94% (32/34) of patients had symptoms. However, it is unclear whether these symptoms were specifically related to SH[5,8,11-18,20-24,26,28,30-33,38,39]. Two patients were asymptomatic[25,27], and there were no data regarding clinical presentation in thirteen patients[6,10,13,15,16,19,40]. Although, in general, symptomatic SHs were usually large or multiple[38], Kassarijan et al[21] presented a case of a child with a single 3.5 cm SH associated with hypertension, proteinuria, weight loss, multiple cutaneous lobular capillary hemangiomas, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type I. On the other hand, these symptoms may not be specifically related to SH.

Over 32% (11/34) of patients experienced some kind of abdominal pain[11,12,17,18,20,22,24,28,33]. Splenomegaly was observed in 22 patients[5,8,12-17,20,22,23,26,30-32,38,39]. In 1 patient, congestive splenomegaly was a consequence of liver cirrhosis, whereas two small SHs were additional findings[15]. Splenomegaly associated with hepatomegaly was present in 3 patients, and in 1 of them a splenorenal shunt was performed in addition to splenectomy[5,8,38]. However, a specific pathological process on the liver was not noted in these patients.

Signs of hypersplenism were present in 8 patients. These children had either a single SH larger than 4.5 cm (diameter range: 4.5-18.0 cm) or multiple splenomas, ranging from a few millimeters to 5 cm[5,8,13,17,20,32,38,39]. Although symptomatic SHs causing hypersplenism in children and adults were mostly larger, Tsitouridis et al[1] reported a 64-year-old patient with a SH 3.5 cm in diameter that caused abnormal splenic overactivity, mimicking hypersplenism. Spleen size and histology were normal and blood counts returned to normal after splenectomy.

Laboratory data were provided for 31 patients. Eighty percent of patients (25/31) had a hematologic abnormality such as anemia[5,8,13,14,16,17,21,23,25,26,32,39,40], thrombocytopenia[8,13,17,18,39], or pancytopenia[8,13,20,32,38], and specific associated diagnoses included bone marrow hyperplasia[8,13,32,38], sickle cell anemia[8,23,27], hereditary spherocytosis[8,16], congenital dyserythropoietic anemia[8], and β thalassemia[17,26]. One patient was diagnosed with splenic lymphoma[16].

Systemic symptoms and signs such as recurrent infections, fever, night sweats, lethargy, weight loss, and growth retardation were reported in 5 patients. These symptoms resolved after splenectomy in all patients[8,17,20,38]. One patient with a 5.4 cm SH presented with parotid swelling accompanied by fever and anorexia[13].

Urinary symptoms and signs in patients with SHs are rare. Serra et al[28] reported a case of a child with 5.5 cm SH that presented with lumbar pain, fever, and microhematuria. Urinary tract infection (UTI) was diagnosed in 2 patients. The first patient underwent radiological evaluation of the UTI, which included ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT), and SH with a diameter of 4.0 cm was found[8,19]. The other patient suffered from recurrent UTIs, which, interestingly, resolved after the removal of the 6.0 cm large SH by PS[22]. Furthermore, proteinuria together with anemia and splenomegaly was reported in a patient with a 7.0 cm SH[13].

The most severe complication of SH is rupture. Such was described in a 3-mo-old child. Despite urgent splenectomy, massive blood loss caused acute renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation leading to a fatal outcome on the fourth day of hospitalization[30].

There were 3 pediatric patients with SH associated with a genetic disorder. In a patient with Alagille syndrome, two SHs (2.5 cm and 4.0 cm) were postmortem findings. The genetic disorder in this syndrome consisted of JAG1 mutations and impaired Notch signaling. Disruption of Notch signaling affects angiogenesis and arteriogenesis and might lead to various cardiovascular anomalies observed in Alagille syndrome including ventricular septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot, peripheral pulmonic artery stenosis, and coarctation of aorta. In addition, disruption of this signaling pathway is also related to the development of some vascular tumors including infantile hemangiomas and angiosarcomas[31]. Subsequently, it might be possible that the SHs in this patient were also a consequence of the Notch signaling disorder. The second patient suffered from Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome, a disorder characterized by immunodeficiency and microthrombocytopenia[13]. The third patient from this group was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis, a genetic disease characterized by non-cancerous tumors that may appear in many vital organs. There is a possibility that the SH in this patient might be part of the tuberous sclerosis complex[6].

RADIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF SH IN CHILDREN

Although the final diagnosis of SH depends on histopathological evaluation, advances in imaging modalities provide the possibility of a preoperative assumption of the diagnosis. SH is often discovered incidentally during radiological evaluation for other reasons. Although it is a rare benign entity, it can be challenging to differentiate from some malignant splenic diseases[25,29,41]. Adequate preoperative diagnosis helps a surgeon to decide whether to proceed with a spleen-preserving procedure, sparing essential functions of the spleen and avoiding complications of a total splenectomy (TS), especially in the pediatric population[42-44]. In patients presented in this review, various imaging modalities including US[6], color Doppler[12], contrast-enhanced US[24], CT[29], positron emission tomography-CT[25], scintigraphy, angiography[14], and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[6] were used for the evaluation of SH.

Twenty-five patients from this review, including our case, underwent US[8,11-14,17,18,20-22,25,27,28,30,33,45]. In 5 patients, this diagnostic modality detected only splenomegaly but not a focal lesion[8,13]. On the US, SH is usually a well-defined solid mass but may have varying echogenicity[13,41,45,46]. Rarely, it may contain calcifications, cysts, or hemorrhage, appearing heterogeneous to normal splenic parenchyma[47,48], as presented by Thompson et al[20] and Serra et al[28]. Some SHs appeared as hyperechoic solid lesions compared to the adjacent normal splenic parenchyma[6,22,27]. In contrast, in multiple cases including ours, SHs were hypoechoic, most likely due to the predominant composition of red pulp with a lack of white pulp and fibrous trabeculae[6,11,12,21,25,33]. Finally, Zhang et al[12] presented a patient with a well-defined isoechoic mass representing SH.

On color Doppler images, SH is often characterized by increased blood flow representing the hypervascularity of the red pulp[12,24,25,28]. Tatekawa et al[24] performed contrast-enhanced US using Levovist, confirming the hypervascularity of SH previously detected on color Doppler imaging. Some authors detected the hypervascular appearance of the lesion by performing an angiogram[14,18], while in the case presented by Silverman et al[5], a large, relatively avascular mass was demonstrated.

CT was performed in 15 children with SH[8,12,13,17,18,20-22,24,26,29,31-33,40]. On plain and contrast-enhanced CT images, SHs usually appeared as heterogeneous masses[12,17,20,24,26,29], sometimes containing areas of lower density suggesting necrosis or hemorrhage as presented by Havlik et al[17] or calcifications as reported by Giambelluca et al[26]. In some cases, CT could not delineate the lesion[8,13,21] or demonstrate a focal lesion with decreased attenuation[32]. Avila et al[25] performed positron emission tomography-CT, showing a moderate uptake of fluorine 18-labeled fluorodeoxyglucose in a low-attenuating splenic mass.

Scintigraphy was performed in 6 cases[13,14,17,18,20,21]. In a patient presented by Hayes et al[13], only splenomegaly without a shift in radionuclide uptake was noted. Similarly, Kassarjian et al[21] reported a case with a focal area of absence of uptake at the spot of SH. Furthermore, a faint uptake was noted in 3 patients[14,17,20], while Okada et al[18] reported a SH case with increased activity on radionuclide scintigraphy correlating with a hypervascular mass detected by other imaging methods.

Among 47 patients presented in this article, MRI was used in a diagnosis of SH in 14[6,8,11,12,20,21,24,28,30,31]. Most authors found that SH appeared hyperintense on T2-weighted (T2W) MRI[6,12,20,21]. Less frequently, hypointense or intermediate signal compared to normal splenic tissue was described[6,11]. The appearance of SH on T1-weighted MRI was inconsistent, presenting as a hypointense[12,21], isointense[20], or hyperintense mass[10,12]. Postcontrast images usually showed diffuse homogenous or heterogeneous enhancement, indicating the vascular nature of the lesions[6,12,21]. Tatekawa et al[24] performed superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced MRI that showed a decrease in signal intensity on T2W gradient-echo imaging. These distinct MRI findings are considered to represent different histological types including fibrous and non-fibrous SH[20,41,49,50]. In a recent paper, Sabra et al[11] demonstrated no significant restriction of diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging MRI.

The most common radiological differential diagnoses of SH are hemangioma[12,21,28] and some other benign lesions like inflammatory pseudotumor[12,25]. Sometimes, SH may resemble some malignant lesions, which makes it hard to choose the appropriate therapeutic approach. Malignancies that are often mentioned as possible differential diagnoses are lymphoma[12,25,27], angiosarcoma[12,27], or metastases in cases of multiple lesions[27].

PATHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF SH

Gross

SHs are represented by one or more well-circumscribed, unencapsulated, solid nodules[27].

Microscopic

SHs are composed of an abnormal cluster of the splenic red pulp presenting as irregularly arranged vascular channels of varying sizes, lined by splenic sinus endothelium (littoral cells) surrounded by fibrotic splenic (Billroth) cords. These lesions lack the white pulp. Scattered lymphocytes and histiocytes may be present throughout the stroma, along with other inflammatory cells and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Other features that may be found are fibrosis, calcified areas, hemosiderin, and adipocytes. The transition of the lesion to the surrounding parenchyma of the spleen is gradual[8]. The splenic parenchyma around the lesion is compressed without the formation of a pseudocapsule[51]. In rare case reports, stromal cell proliferation in SH has been described with the presence of larger, atypical, mononuclear cells[25] or bizarre stromal cells[3].

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is important in distinguishing hamartoma from other vascular neoplasms of the spleen. As endothelial cells of SH originate from splenic-type endothelial cells, their key feature is CD8 positivity[9]. Along with this, these cells are positive for CD31, vimentin, and factor VIII–related antigen but negative for CD21 antibody. CD34 exerts inconsistent staining of vascular spaces in SH according to different studies, but it is mostly negative. CD68 is positive in stromal macrophages but negative in the lining cells of the vascular spaces. The Ki-67 (also referred to as MIB-1) proliferative index is low, being expressed in less than 5% of endothelial cells in the nodule[8].

The main pathological differential diagnosis is with benign vascular tumors such as hemangiomas and littoral cell angiomas. In hemangiomas, endothelial cells are positive for endothelial markers including CD31 and CD34 and negative for CD8, CD21, and CD68. In littoral cell angiomas, the lining cells are positive for both endothelial and histiocytic markers CD31 and CD68 and negative for CD8 and CD34. CD21 is reported to be exclusively positive in littoral cell angiomas[9].

TREATMENT OF SH IN CHILDREN

A need for histopathological specimens and the possibility of complications of the SH in children make surgery the first choice in the treatment of this lesion. Surgical resection can be achieved by TS or PS. The choice of surgical procedure must be based on the number, site, and size of the lesions, the patient’s age, and possible postoperative impairment to immune function. The indications for splenectomy in our study included splenic mass, severe anemia in hematological disorders, sequestration crisis, hypersplenism, splenomegaly, and spontaneous splenic rupture. Splenectomy was performed in 46 children, whereas in 1 patient SH was a postmortem finding.

TS ensures the complete removal of the pathological process in the spleen but makes patients susceptible to a variety of different infections, especially the ones caused by encapsulated organisms as they are more resilient to phagocytosis. The most concerning complication of TS is overwhelming post-splenectomy infection, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates. The incidence of fatal infection in asplenic children is about ten times higher than in the control population[52]. Younger age at splenectomy is an important risk factor for infection[53]. In addition, TS is associated with a higher risk of thromboembolic events, such as portal vein thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and according to some studies-pulmonary hypertension[54-56]. Still, TS is the most frequently performed procedure for the treatment of SHs. The factors that usually indicate TS are large size, central localization, and unclear etiology of the lesion, as well as the experience of the operator[44,57,58]. In children with SH, 35 TS were performed. Open TS (OTS) was performed in 21 patients. Among these, 7 cases specifically stated that OTS was performed[5,11,14,18,27,33,40]. The next 14 cases were reported before the first publication of LS. Therefore, we presumed that the open approach was applied[13,15,16,30,38,39]. The remaining 14 cases were reported after the first report of LS and there were not enough data to conclude whether an OTS or laparoscopic TS was performed[6,8,12,13,20,23,26,32].

LS is the technique of choice for the surgical treatment of SHs, offering the benefits of a minimally invasive approach. However, LS may be very hard to perform in an extremely large spleen when the space in the child’s abdomen limits the handling of laparoscopic instruments and the spleen. Moreover, LS requires a highly trained surgeon and adequate laparoscopic equipment. In children with SH, four laparoscopic TSs were performed[10,24,25].

PS comprises removing 70%-80% of the spleen. It has been shown in experimental models that the remaining 25%-30% of the initial splenic tissue may provide sufficient immune activity[59]. PS is suitable for small-to moderate-sized lesions, not centrally located, and having well-defined margins[10]. However, PS may be a difficult surgical procedure requiring familiarity with the end-vascular distribution of intrasplenic vessels and the competence to deal with significant bleeding that may occur during tissue dissection.

In children with SH, five open PSs, including our case[17,19,21,22], and two laparoscopic PSs (LPSs) were performed[10,28]. Although the LPS seems to be the most beneficial procedure for SH treatment, reliable data on the risk-benefit ratio of LPS has not yet been precisely defined[60]. An accurate preoperative image study enables PS planning. Furthermore, the risk of bleeding during dissection of the spleen parenchyma in PS may be prevented by preoperative angiography and embolization of the affected spleen pole. This procedure was performed in a child with upper pole SH presented by Serra et al[28]. Malignancy was ruled out by intraoperative histological examination of the frozen section, and then a LPS was performed.

Furthermore, malignancy may be ruled out preoperatively by minimally invasive diagnostic procedures such as fine needle aspiration cytology or image-guided core needle biopsy. However, there is the possibility of diagnostic inaccuracy and procedural complications, such as bleeding or seeding the neoplastic cells into the abdominal cavity in case of malignancies[25,28,61].

In the majority of patients with symptomatic SH or hematological laboratory abnormalities, there was a resolution of symptoms and resolution or improvement of laboratory findings after PS or TS[5,8,12,13,17,20-22,28,32,38]. However, when TS is performed, it is not clear whether the hematological resolution or improvement results from spleen removal or from the hamartoma elimination. On the other hand, case reports of PS (nodulectomy) in children with SH, such as our case, suggest that a favorable clinical-hematological response to splenectomy may be related to the removal of these “tumors”[17,21,28].

CONCLUSION

SHs in children may be asymptomatic or present with abdominal pain, splenomegaly, systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, lethargy, growth retardation, and weight loss, or signs and symptoms that result from hypersplenism and subsequent cytopenias.

SH may be indicated by the presence of a well-circumscribed homogenous solid mass in US imaging with increased blood flow on color Doppler images. On non-enhanced CT, SH is usually a heterogenous mass while appearing hyperintense on T2W MRI and showing diffuse post-contrast enhancement.

Surgical treatment, including PS or TS, represents the cornerstone of the management of SH. Most of the children analyzed in this review underwent symptom resolution and improvement or resolution of cytopenias after surgical removal of the SH. However, in some cases, it was not clear whether the hematological resolution or improvement was a consequence of the splenectomy or the removal of the hamartoma. PS preserves the immunologic functions of the spleen and is suitable for small-to moderate-sized peripherally located lesions with well-defined margins. Still, TS is the most frequently performed procedure for the treatment of SHs in pediatric patients, and it is usually indicated by large size, central localization, unclear etiology of the lesion, and the experience of the operator.

Finally, the definitive confirmation of SH is based on histopathological analysis. The main differential diagnosis comprises benign vascular tumors such as hemangioma and littoral cell angioma, that may be differentiated by immunohistochemistry.

This review has some limitations. First, the study included a small number of cases and not all analyzed characteristics were available for all patients. Moreover, data in some cases were extracted from an abstract or cited text without having insight into the entire original article.