Published online Apr 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1793

Peer-review started: October 29, 2023

First decision: January 17, 2024

Revised: February 3, 2024

Accepted: March 12, 2024

Article in press: March 12, 2024

Published online: April 6, 2024

Processing time: 148 Days and 17.7 Hours

Whether hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) can cause paradoxical herniation is still unclear.

A 65-year-old patient who was comatose due to brain trauma underwent decompressive craniotomy and gradually regained consciousness after surgery. HBOT was administered 22 d after surgery due to speech impairment. Para

Paradoxical herniation is rare and may be caused by HBOT. However, the un

Core Tip: Paradoxical herniation may be caused by high-pressure oxygen therapy after decompressive craniectomy has not been reported. Paradoxical herniation has been misdiagnosed by the neurosurgery department of subordinate hospitals and provincial neurological rehabilitation hospitals for many times, thus delaying treatment. This report is to improve the understanding of paradoxical herniation.

- Citation: Ye ZX, Fu XX, Wu YZ, Lin L, Xie LQ, Hu YL, Zhou Y, You ZG, Lin H. Paradoxical herniation associated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy after decompressive craniectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(10): 1793-1798

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i10/1793.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i10.1793

Decompression with a bone flap is an effective rescue measure for alleviating various types of malignant intracranial hypertension. After cerebral edema subsides, the skull loses mechanical support, and the force generated by atmospheric pressure directly acts on the skull defect site. This causes the flap to sag after collapsing downward and inward, leading to a series of neurological declines. The mechanism by which paradoxical herniation occurs remains unclear because it is relatively rare. Moreover, many doctors do not have a comprehensive understanding of this disease, which can lead to misdiagnosis, missed diagnosis, or even deterioration of the patient’s condition and, in severe cases, death. We encountered a rare patient with paradoxical herniation caused by hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) that was misdiagnosed. Here we report such case to improve the understanding of this disease.

A 65-year-old male patient was in a coma for more than a month due to a high fall.

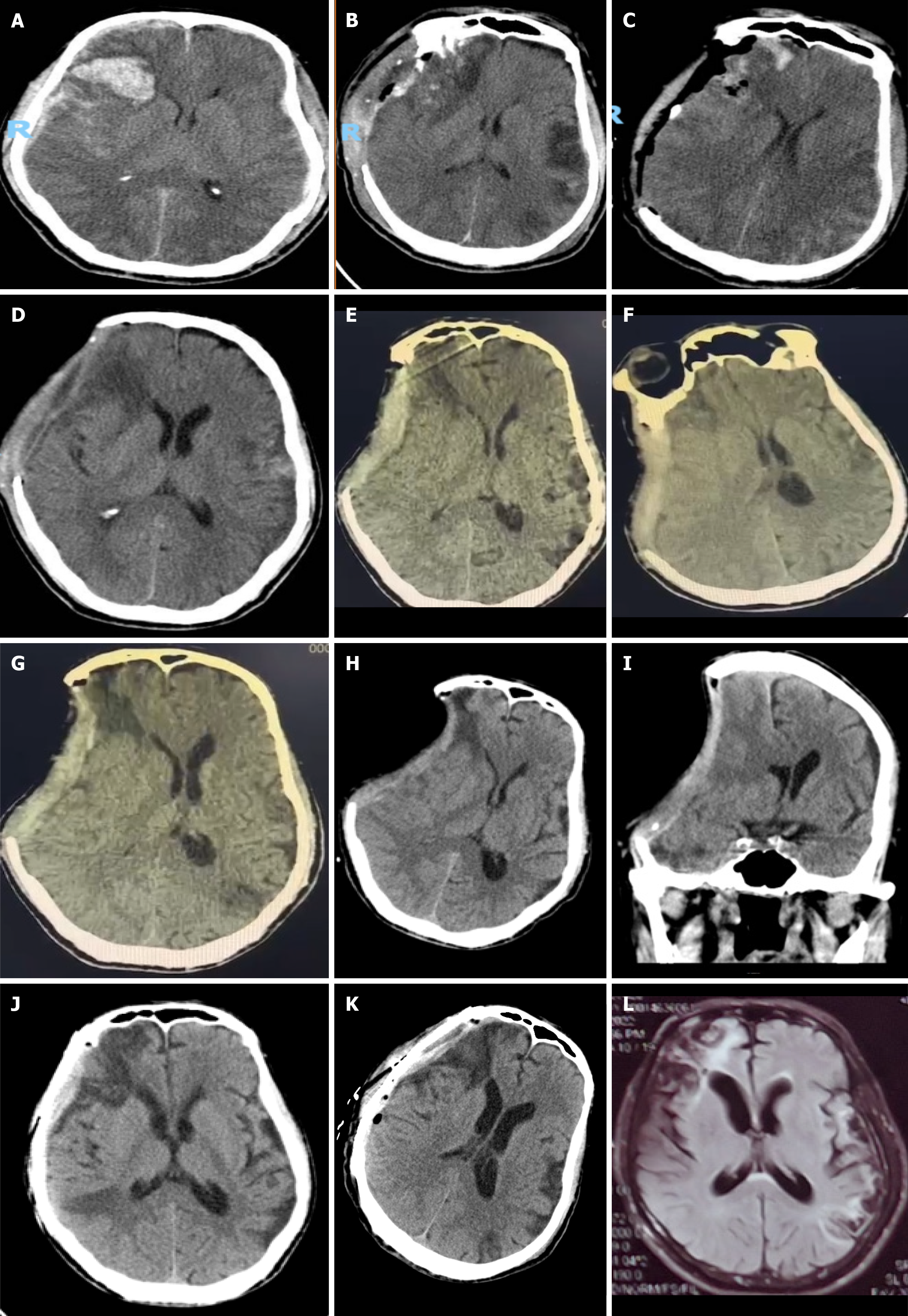

A 65-year-old male patient presented to Zhangping City Hospital in Fujian Province on May 2, 2021 (Figure 1A) with loss of consciousness for 20 min following a fall from a high height. Cranial computed tomography (CT) revealed a bilateral acute temporal subdural hematoma and contusion in the right frontotemporal lobe. The patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent physical examination. The Glasgow Coma Scale score of the patient was 7 (E1, V2, M4), and he was slightly unconscious, irritable, and unable to answer and cooperate during examination. The bilateral pupils were equally round and large, 0.2 cm in diameter, and slow to respond to light. Lacerations were observed in the left temporal area with obvious local swelling. Bright red bloody fluid was observed in the left external auditory canal and bilateral nasal cavity, with slight resistance in the neck. Lacerations were present in the left thorax, waist, and left anterior abdominal region, with slightly greater muscle tension. The Barnberg sign and Ke's sign were negative. In the Emergency Department, "right craniotomy + intracranial hematoma removal + bone decompression + secondary artificial dural repair" was performed (Figure 1B). After the operation, fluid rehydration therapy, hemostatic agents, nutritional support, brain tissue assessment, infection prevention treatment, stomach protection measures, electrolyte balance therapy, and sedation and analgesia were administered. After the operation (Figure 1C), the patient’s condition gradually improved, but he was unable to speak. On May 24, 2021 (Figure 1D), "hyperbaric oxygen" (inside the cabin, gauge pressure 0.1 mPa, oxygen inhalation for 30 min, rest for 10 min (air inhalation), and oxygen inhalation for 30 min) was administered. The next day (May 25, 2021, Figure 1E), the bone window collapse was obvious; however, local doctors considered it to be normal and thus continued two courses of hyperbaric oxygen treatment. The duration of each treatment course was 10 d, and the degree of bone window collapse did not significantly improve. The patient’s family considered that the treatment response was poor due to his speech disturbance, dysphagia, and occasional dizziness. On June 14, 2021, the patient was transferred to a higher-level hospital for rehabilitation treatment, and on June 15, 202, he was transferred to the Rehabilitation Hospital Affiliated with Fujian University of Chinese Medicine. On the day after admission, cranial CT examination revealed paradoxical herniation (Figure 1F). An attempt to lower cranial pressure using mannitol resulted in drowsiness. On June 17, 2021 (Figure 1G), craniocerebral CT revealed worsened paradoxical herniation, and further treatment was not effective. Five days later (June 22, 2021), a craniocerebral CT review revealed no improvement, and consultation was requested due to continued drowsiness. The patient was referred to our hospital on June 25, 2021, at which point the effects of fluid rehydration were unsatisfactory. A review of the craniocerebral CT images revealed that the paradoxical herniation was still present (June 27, 2021; Figure 1H and I). Cranioplasty was performed on July 1, 2021 (Figure 1J), and the patient was no longer drowsy on the second day after surgery. The stitches were removed, and the patient was discharged from the hospital one week later.

The patient had a medical history of pulmonary tuberculosis.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors or other genetic conditions.

The vital signs of the patient were as follows: Body temperature, 36.9 °C; heart rate, 68/min; respiratory rate, 20/min; and blood pressure, 123/83 mmHg.

Laboratory examinations showed no abnormalities.

Cranial CT showed the presence of paradoxical herniation on the next day of HBOT initiation (May 25, 2021, Figure 1E), abnormal aggravation of the cerebral hernia on June 17, 2021 after receiving mannitol treatment (Figure 1G), and the disappearance of paradoxical herniation following cranioplasty on July 1, 2021 (Figure 1J).

Paradoxical herniation associated with HBOT.

After the patient’s skull was repaired, the paradoxical herniation disappeared.

At the postoperative follow-up visit, the patient was mentally clear. Repeat magnetic resonance imaging showed that the paradoxical herniation did not reappear. The patient’s speech gradually improved (Figure 1).

Paradoxical herniation, also known as paradoxical herniation syndrome or acute progressive hypotension syndrome, was first described by Schwab et al[1] in 1998 as the result of the absence of a portion of the skull after craniotomy. Cere

HBOT-induced paradoxical herniation has not been reported in the literature. However, whether it affects CSF cir

Ignoring the nature of the high compliance and low cranial pressure associated with disordered CSF dynamics, attempting to drain CSF, or using dehydrating agents to change its abnormal distribution will further exacerbate disordered CSF dynamics, destroy the homeostasis of the central nervous system, and seriously worsen nerve function. Because doctors, including neurosurgeons[14] and neurorehabilitation doctors, have some deficiencies in understanding this phenomenon, mannitol dehydration treatment is often administered immediately after the discovery of a cerebral hernia. This method of treatment has been a standard protocol for a long time but results in worsening of both paradoxical herniation and consciousness disorders, thereby affecting patient rehabilitation.

Intracranial pressure can be effectively reduced by placing the patient in the low-head and high-foot supine position[15], discontinuing drugs that promote dehydration, increasing the intravenous fluid supply, eliminating all factors leading to CSF loss (lumbar cisternal drainage, ventriculoperitoneal shingles, and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea and otorrhea), and restoring skull integrity as soon as possible. Restoring the integrity of the skull is not only the aim of treatment for paradoxical herniation[12,13,15] but also a means to improve the blood supply to the brain on the skull defect side in patients with paradoxical herniation and to aid in the recovery of nerve function.

In summary, paradoxical herniation is a rare complication after decompressive craniotomy, but its pathological mechanism is unknown. HBOT may cause paradoxical herniation after decompressive craniotomy. However, due to the limitations of single cases, further studies are needed to confirm the exact role of HBOT in the pathogenesis of paradoxical herniation. To improve the in-depth understanding of paradoxical herniation, early diagnosis and timely detection are necessary to ensure timely implementation of effective treatment measures, such as skull repair. Moreover, effective treatment measures are beneficial for repairing the peripheral nerves of lesions and improving patient prognosis.

HBOT may cause paradoxical herniation after decompressive craniotomy. Early diagnosis and timely detection are necessary to ensure timely implementation of effective treatment measures, such as skull repair.

| 1. | Schwab S, Erbguth F, Aschoff A, Orberk E, Spranger M, Hacke W. ["Paradoxical" herniation after decompressive trephining]. Nervenarzt. 1998;69:896-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Greitz D, Franck A, Nordell B. On the pulsatile nature of intracranial and spinal CSF-circulation demonstrated by MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 1993;34:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wagshul ME, Eide PK, Madsen JR. The pulsating brain: A review of experimental and clinical studies of intracranial pulsatility. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2011;8:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Idris Z, Mustapha M, Abdullah JM. Microgravity environment and compensatory: Decompensatory phases for intracranial hypertension form new perspectives to explain mechanism underlying communicating hydrocephalus and its related disorders. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9:7-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Creutzfeldt CJ, Vilela MD, Longstreth WT Jr. Paradoxical herniation after decompressive craniectomy provoked by lumbar puncture or ventriculoperitoneal shunting. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:1170-1175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Watanabe J, Maruya J, Nishimaki K. Sinking skin flap syndrome after unilateral cranioplasty and ventriculoperitoneal shunt in a patient with bilateral decompressive craniectomy. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2016;5:6-8. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nasi D, Dobran M, Iacoangeli M, Di Somma L, Gladi M, Scerrati M. Paradoxical Brain Herniation After Decompressive Craniectomy Provoked by Drainage of Subdural Hygroma. World Neurosurg. 2016;91:673.e1-673.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Shen L, Qiu S, Su Z, Ma X, Yan R. Lumbar puncture as possible cause of sudden paradoxical herniation in patient with previous decompressive craniectomy: report of two cases. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao J, Li G, Zhang Y, Zhu X, Hou K. Sinking skin flap syndrome and paradoxical herniation secondary to lumbar drainage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;133:6-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galbiati G, Paola C. Effects of Open and Closed Endotracheal Suctioning on Intracranial Pressure and Cerebral Perfusion Pressure in Adult Patients With Severe Brain Injury: A Literature Review. J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;47:239-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wee HY, Kuo JR. Never neglect the atmospheric pressure effect on a brain with a skull defect. Int Med Case Rep J. 2014;7:67-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hiruta R, Jinguji S, Sato T, Murakami Y, Bakhit M, Kuromi Y, Oda K, Fujii M, Sakuma J, Saito K. Acute paradoxical brain herniation after decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury: A case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Bender PD, Brown AEC. Head of the Bed Down: Paradoxical Management for Paradoxical Herniation. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jung HJ, Kim DM, Kim SW. Paradoxical transtentorial herniation caused by lumbar puncture after decompressive craniectomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;51:102-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Narro-Donate JM, Huete-Allut A, Escribano-Mesa JA, Rodríguez-Martínez V, Contreras-Jiménez A, Masegosa-González J. [Paradoxical transtentorial herniation, extreme trephined syndrome sign: A case report]. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2015;26:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: China Medical Education Association, ETCHB-203.

Specialty type: Neurosciences

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shen HN, Taiwan S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhao S